Abkhazia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→Demographics: this info is taken from the book by Mrs. Chervonnaya; see talkpage |

||

| Line 114: | Line 114: | ||

According to the Family Lists compiled in 1886 (published 1893 in Tbilisi) the Sukhumi District's population was 68,773, of which 30,640 were Samurzaq'anoans, 28,323 [[Abkhaz]], 3,558 [[Mingrelians]], 2,149 [[Greeks]], 1,090 [[Armenians]], 1,090 [[Russians]] and 608 [[Georgians]] {{Fact|date=May 2007}} (including Imeretians and Gurians). Samurzaq'ano is a present-day [[Gali]] region of Abkhazia. Most of the Samurzaq'anians must be thought to have been Mingrelians, and a minority Abkhaz.<ref>Cornell, Svante E. (2001), Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, p. 156. Routledge (UK), ISBN 0700711627)</ref><ref> Müller, D, 1999. ''Demography: ethno-demographic history, 1886-1989'' in The Abkhazians: A handbook. Richmond: Curzon Press.</ref> |

According to the Family Lists compiled in 1886 (published 1893 in Tbilisi) the Sukhumi District's population was 68,773, of which 30,640 were Samurzaq'anoans, 28,323 [[Abkhaz]], 3,558 [[Mingrelians]], 2,149 [[Greeks]], 1,090 [[Armenians]], 1,090 [[Russians]] and 608 [[Georgians]] {{Fact|date=May 2007}} (including Imeretians and Gurians). Samurzaq'ano is a present-day [[Gali]] region of Abkhazia. Most of the Samurzaq'anians must be thought to have been Mingrelians, and a minority Abkhaz.<ref>Cornell, Svante E. (2001), Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, p. 156. Routledge (UK), ISBN 0700711627)</ref><ref> Müller, D, 1999. ''Demography: ethno-demographic history, 1886-1989'' in The Abkhazians: A handbook. Richmond: Curzon Press.</ref> |

||

According to the 1897 Russian census Abkhaz (by mother tongue) numbered 59,469 in [[Kutaisi]] guberniya.<ref>[http://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_lan_97.php?reg=101 Kutais guberniya census results, 1897]</ref> This guberniya included Sukhumi district (Abkhazia) at that time where almost all of the Abkhaz lived. The population of the Sukhumi district itself was about 100,000 at that time. Greeks, Russians and Armenians composed 3.5%, 2% and 1.5% of the district's population.<ref>[http://www.cultinfo.ru/fulltext/1/001/007/098/98427.htm Sukhum, Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedia]</ref> |

|||

According to the 1917 agricultural census organized by the [[Russian Provisional Government]], Georgians and Abkhaz composed 41.7% (54,760) and 30,4% (39,915) of the rural population of Abkhazia respectively.<ref>Ментешашвили А.М. Исторические предпосылки современного сепаратизма в Грузии. - Тбилиси, 1998. [http://sisauri.tripod.com/politic/doc1.html]</ref> At that time Gagra and its vicinity weren't part of Abkhazia. |

According to the 1917 agricultural census organized by the [[Russian Provisional Government]], Georgians and Abkhaz composed 41.7% (54,760) and 30,4% (39,915) of the rural population of Abkhazia respectively.<ref>Ментешашвили А.М. Исторические предпосылки современного сепаратизма в Грузии. - Тбилиси, 1998. [http://sisauri.tripod.com/politic/doc1.html]</ref> At that time Gagra and its vicinity weren't part of Abkhazia. |

||

The following table summarises the results of the censuses carried out in Abkhazia. The Russian, Armenian and Georgian population grew faster than Abkhaz one due to the large-scale immigration |

The following table summarises the results of the censuses carried out in Abkhazia. The Russian, Armenian and Georgian population grew faster than Abkhaz one due to the large-scale immigration.<ref>[http://www.cdi.org/russia/johnson/8226.cfm JRL RESEARCH & ANALYTICAL SUPPLEMENT ~ JRL 8226, Issue No. 24 • May 2004. SPECIAL ISSUE; THE GEORGIAN-ABKHAZ CONFLICT: PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE]</ref> |

||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

| Line 129: | Line 127: | ||

!Armenians |

!Armenians |

||

!Greeks |

!Greeks |

||

|- |

|||

|1897 Census<big>{{rf|1|***}}</big> |

|||

| |

|||

|25,640 |

|||

|58,697 |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1926 Census |

|1926 Census |

||

| Line 178: | Line 184: | ||

|14,664 |

|14,664 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|2003 Census<big>{{rf| |

|2003 Census<big>{{rf|2|***}}</big> |

||

|215,972 |

|215,972 |

||

|45,953 |

|45,953 |

||

| Line 187: | Line 193: | ||

|} |

|} |

||

<big>{{ent|1|***}}</big> -<ref name = "2003 Census statistics (in Russian)">[http://www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru/rnabkhazia.html] 2003 Census statistics {{ru icon}}</ref> Georgian authorities did not acknowledge the results of this census and consider it illegitimate. Several international sources also consider these figures unrealistically high. The [[International Crisis Group]] (2006) estimates Abkhazia's total population to be between 157,000 and 190,000 (or between 180,000 and 220,000 as estimated by [[UNDP]] in 1998),<ref>The [[International Crisis Group]]. ''Abkhazia Today. Europe Report N°176'', p. 9. [[15 September]] [[2006]].</ref> while [[Encyclopædia Britannica]] puts it at 177,000 (2006 est.).<ref>"Georgia." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. [http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9433195 Encyclopædia Britannica Online]. 30 Apr. 2007.</ref> The State Department of Statistics of Georgia estimated, in 2005, Abkhazia's population to be approximately 178,000.<ref>http://www.statistics.ge/Main/Yearbook/2005/05Population_05.doc Statistical Yearbook of Georgia, 2005: Population] (607kb, ''[[Microsoft Word Document]]''). The State Department of Statistics of Georgia. Retrieved on [[April 30]], [[2007]].</ref> About 2,000 people (predominantly ethnic [[Georgians]]) live in Georgia-controlled Upper Abkhazia. |

<big>{{ent|1|***}}</big> -<ref>1-я Всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Кутаисская губерния. Спб: 1905. С. 32</ref>. The population of the Sukhumi district (Abkhazia) was about 100,000 at that time. Greeks, Russians and Armenians composed 3.5%, 2% and 1.5% of the district's population.<ref>[http://www.cultinfo.ru/fulltext/1/001/007/098/98427.htm Sukhum, Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedia]</ref> |

||

<big>{{ent|2|***}}</big> -<ref name = "2003 Census statistics (in Russian)">[http://www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru/rnabkhazia.html] 2003 Census statistics {{ru icon}}</ref> Georgian authorities did not acknowledge the results of this census and consider it illegitimate. Several international sources also consider these figures unrealistically high. The [[International Crisis Group]] (2006) estimates Abkhazia's total population to be between 157,000 and 190,000 (or between 180,000 and 220,000 as estimated by [[UNDP]] in 1998),<ref>The [[International Crisis Group]]. ''Abkhazia Today. Europe Report N°176'', p. 9. [[15 September]] [[2006]].</ref> while [[Encyclopædia Britannica]] puts it at 177,000 (2006 est.).<ref>"Georgia." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. [http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9433195 Encyclopædia Britannica Online]. 30 Apr. 2007.</ref> The State Department of Statistics of Georgia estimated, in 2005, Abkhazia's population to be approximately 178,000.<ref>http://www.statistics.ge/Main/Yearbook/2005/05Population_05.doc Statistical Yearbook of Georgia, 2005: Population] (607kb, ''[[Microsoft Word Document]]''). The State Department of Statistics of Georgia. Retrieved on [[April 30]], [[2007]].</ref> About 2,000 people (predominantly ethnic [[Georgians]]) live in Georgia-controlled Upper Abkhazia. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 19:53, 10 May 2007

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

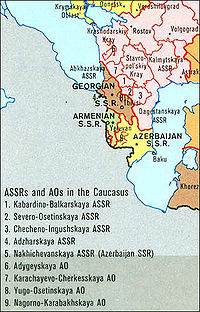

Abkhazia IPA: /æbˈkeɪʒə/ or /æbˈkɑziə/ (Template:Lang-ab Apsny, Georgian: აფხაზეთი Apkhazeti, or Abkhazeti, Template:Lang-ru Abhazia) is a de facto independent republic located on the eastern coast of the Black Sea, bordering the Russian Federation to the north, and within the internationally recognised borders of Georgia. Abkhazia’s independence is not recognized by any international organization or country and it is regarded as an autonomous republic of Georgia (Georgian: აფხაზეთის ავტონომიური რესპუბლიკა, Abkhaz: Аҧснытәи Автономтәи Республика), with Sukhumi as its capital.

A secessionist movement of Abkhaz ethnic minority in the region led to the declaration of independence from Georgia in 1992 and the Georgian-Abkhaz armed conflict from 1992 to 1993 which resulted in the Georgian military defeat and the mass exodus of ethnic Georgian population from Abkhazia. In spite of the 1994 ceasefire accord and the ongoing UN-monitored CIS peacekeeping operation, the sovereignty dispute has not yet been resolved and the region remains divided between the two rival authorities, with over 83 percent of its territory controlled by the Russian-backed Sukhumi-based separatist government and about 17 percent governed by the representatives of the de jure Government of Abkhazia, the only body internationally recognized as a legal authority of Abkhazia, located in the Kodori Valley, part of Georgian-controlled Upper Abkhazia.

Political status

The international organizations such as United Nations (28 Security Council Resolutions), EC, OSCE, NATO, WTO, Council of the European Union, CIS as well as most sovereign states recognize Abkhazia as an integral part of Georgia and support its territorial integrity according to the principles of the international law. The United Nations is urging both sides to settle the dispute through diplomatic dialogue and ratifying the final status of Abkhazia in the Georgian Constitution.[1][2] However, the Abkhaz de-facto government and the majority [citation needed] of current Abkhazia's population (excluding ethnic Georgians who still populate the Gali District and the Kodori Gorge) consider Abkhazia a sovereign country, even though not recognized by any party in the world. In 2005, the Georgian government offered Abkhazia high degree of autonomy and possible federal structure within borders and jurisdiction of Georgia.

Meanwhile the Russian State Duma is urging to take into consideration the appeal made by Abkhaz de facto authorities which calls for recognition of its independence,[3] while Russian state media produce numerous materials in support of the separatist regime.[4] During the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict, Russian authorities and military supplied logistical and military aid to the separatist side.[1] Today, Russia still maintains a strong political and military influence over the separatist rule in Abkhazia.[5] Additionally, the Russian Orthodox Church recently published translations of the Gospels in Abkhazian, which drew protests from the Georgian Orthodox and Apostolic Church as a violation of Orthodox Church canon law, constituting a meddling in the internal affairs of another Orthodox church and annexation of Georgian Orthodox property in Abkhazia.[6]

On October 18, 2006, the Abkhaz de facto parliament passed a resolution, calling upon Russia, international organizations, and the rest of the international community to recognize Abkhaz independence on the basis that Abkhazia possesses all the properties of an independent state.[7] However, international organizations have confirmed their support for Georgian territorial integrity and outlined the basic principles of conflict resolution which calls for immediate return of all expelled ethnic Georgian refugees (approximately 250,000) and involvement of International Police to monitor the safety of all ethnic groups living in Abkhazia.[8] About 60,000 Georgian refugees have spontaneously returned to Abkhazia's Gali district since 1994, but tens of thousands were displaced again when fighting resumed in the Gali district in 1998. Nevertheless from 40,000 to 60,000 refugees have returned to Gali district since 1998, including persons commuting daily across the ceasefire line and those migrating seasonally in accordance with agricultural cycles.[9] In the Georgian-populated areas in Gali district, where local authorities are almost exclusively made up of ethnic Abkhaz, human right situation remains precarious. The United Nations and other international organizations have been fruitlessly urging the Abkhaz de facto authorities "to refrain from adopting measures incompatible with the right to return and with international human rights standards, such as discriminatory legislation… [and] to cooperate in the establishment of a permanent international human rights office in Gali and to admit United Nations civilian police without further delay."[10]

Georgia accuses the Abkhaz secessionists of having conducted a deliberate campaign of ethnic cleansing, a claim supported by the OSCE and many Western governments. The UN Security Council has, however, avoided use of the term "ethnic cleansing", but has affirmed "the unacceptability of the demographic changes resulting from the conflict"[11]

Geography and climate

Abkhazia covers an area of about 8,600 km² at the western end of Georgia. The Caucasus Mountains to the north and the northeast divide Abkhazia from the Russian Federation. To the east and southeast, Abkhazia is bounded by the Georgian region of Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti; and on the south and southwest by the Black Sea.

Abkhazia is extremely mountainous. The Greater Caucasus Mountain Range runs along the region's northern border, with its spurs – the Gagra, Bziphi, and Kodori ranges – dividing the area into a number of deep, well-watered valleys. The highest peaks of Abkhazia are in the northeast and east and several exceed 4,000 meters (13,120 feet) above sea level. The landscapes of Abkhazia range from coastal forests and citrus plantations, to eternal snows and glaciers to the north of the region. Although Abkhazia's complex topographic setting have spared most of the territory from significant human development, its cultivated fertile lands produce tea, tobacco, wine and fruits, a mainstay of local agricultural sector.

Abkhazia is richly irrigated by small rivers originating in the Caucasus Mountains. Chief of these are: Kodori, Bzyb, Ghalidzga, and Gumista. The Psou River separates the region from Russia, and the Inguri serves as a boundary between Abkhazia and Georgia proper. There are several periglacial and crater lakes in mountainous Abkhazia. Lake Ritsa is the most important of them.

Because of Abkhazia's proximity to the Black Sea and the shield of the Caucasus Mountains, the region's climate is very mild. The coastal areas of the republic have a subtropical climate, where the average annual temperature in most regions is around 15 degrees Celsius. The climate at higher elevations varies from maritime mountainous to cold and summerless. Abkhazia receives high amounts of precipitation, but its unique micro-climate (transitional from subtropical to mountain) along most of its coast causes lower levels of humidity. The annual precipitation vacillates from 1,100-1,500 mm (43-59 inches) along the coast to 1,700-3,500 mm (67-138 in.) in the higher mountainous areas. The mountains of Abkhazia receive significant amounts of snow.

Economy

The economy of Abkhazia is heavily dependent on Russia and the Russian ruble is used for currency. Tourism is a key industry. Abkhaz de facto authorities claim that the organised tourists (mainly from Russia) numbered more than 100,000 in the last years (compared to about 200,000 in the 1990 before the war)[5] and estimate the total number of visitors in 2006 at 1-1.5 million.[6] Although the CIS economic sanctions imposed against Abkhazia in 1994 are still formally in force and Russia has established a visa regime with Georgia, Russian tourists don’t need a visa to enter Abkhazia.

One of the main sources of electricity of Abkhazia is Inguri hydroelectric power station situated on the border river of Inguri and operated jointly by Abkhaz and Georgians.

A gabbro quarry near the Aigba village on the Psou river is scheduled to begin operations in September 2007. Furthermore, rubble quarries near the Skurcha village (Ochamchira region) and on the Bzyb river will be opening in 2007 as well. It is planned to use its output in the Olympic construction projects in Sochi, as the city is one of the 2014 Winter Olympics bidders.[12]

Abkhazia is also renowned for its agricultural produce, including tea, tobacco, wine and fruits (especially tangerines).

Demographics

According to the Family Lists compiled in 1886 (published 1893 in Tbilisi) the Sukhumi District's population was 68,773, of which 30,640 were Samurzaq'anoans, 28,323 Abkhaz, 3,558 Mingrelians, 2,149 Greeks, 1,090 Armenians, 1,090 Russians and 608 Georgians [citation needed] (including Imeretians and Gurians). Samurzaq'ano is a present-day Gali region of Abkhazia. Most of the Samurzaq'anians must be thought to have been Mingrelians, and a minority Abkhaz.[13][14]

According to the 1917 agricultural census organized by the Russian Provisional Government, Georgians and Abkhaz composed 41.7% (54,760) and 30,4% (39,915) of the rural population of Abkhazia respectively.[15] At that time Gagra and its vicinity weren't part of Abkhazia.

The following table summarises the results of the censuses carried out in Abkhazia. The Russian, Armenian and Georgian population grew faster than Abkhaz one due to the large-scale immigration.[16]

| Year | Total | Georgians | Abkhaz | Russians | Armenians | Greeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1897 Census(refactored from ***) | 25,640 | 58,697 | ||||

| 1926 Census | 186,004 | 67,494 | 55,918 | 12,553 | 25,677 | 14,045 |

| 1939 Census | 311,885 | 91,967 | 56,197 | 60,201 | 49,705 | 34,621 |

| 1959 Census | 404,738 | 158,221 | 61,193 | 86,715 | 64,425 | 9,101 |

| 1970 Census | 486,959 | 199,596 | 77,276 | 92,889 | 74,850 | 13,114 |

| 1979 Census | 486,082 | 213,322 | 83,087 | 79,730 | 73,350 | 13,642 |

| 1989 Census | 525,061 | 239,872 | 93,267 | 74,913 | 76,541 | 14,664 |

| 2003 Census(refactored from ***) | 215,972 | 45,953 | 94,606 | 23,420 | 44,870 | 1,486 |

Template:Ent -[17]. The population of the Sukhumi district (Abkhazia) was about 100,000 at that time. Greeks, Russians and Armenians composed 3.5%, 2% and 1.5% of the district's population.[18] Template:Ent -[19] Georgian authorities did not acknowledge the results of this census and consider it illegitimate. Several international sources also consider these figures unrealistically high. The International Crisis Group (2006) estimates Abkhazia's total population to be between 157,000 and 190,000 (or between 180,000 and 220,000 as estimated by UNDP in 1998),[20] while Encyclopædia Britannica puts it at 177,000 (2006 est.).[21] The State Department of Statistics of Georgia estimated, in 2005, Abkhazia's population to be approximately 178,000.[22] About 2,000 people (predominantly ethnic Georgians) live in Georgia-controlled Upper Abkhazia.

History

Early history

In the 9th–6th centuries BC, the territory of modern Abkhazia became a part of the ancient Georgian kingdom of Colchis (Kolkha), which was absorbed in 63 BC into the Kingdom of Egrisi. Greek traders established ports along the Black Sea shoreline. One of those ports, Dioscurias, eventually developed into modern Sukhumi, Abkhazia's traditional capital.

The Roman Empire conquered Egrisi in the 1st century AD and ruled it until the 4th century, following which it regained a measure of independence, but remained within the Byzantine Empire's sphere of influence. Although the exact time when the population of Abkhazia was converted to Christianity is not determined, it is known that the Metropolitan of Pitius participated in the First Œcumenical Council in 325 in Nicea. Abkhazia was made an autonomous principality of the Byzantine Empire in the 7th century — a status it retained until the 9th century, when it was united with the province of Imereti and became known as the Abkhazian Kingdom. In 9th–10th centuries the Georgian kings tried to unify all the Georgian provinces and in 1001 King Bagrat III Bagrationi became the first king of the unified Georgian Kingdom.

In the 16th century, after the break-up of the united Georgian Kingdom, the area was conquered by the Ottoman Empire, during this time some Abkhazians converted to Islam. The Ottomans were pushed out by the Georgians, who established an autonomous Principality of Abkhazia (abxazetis samtavro in Georgian), ruled by the Shervashidze dynasty (aka Sharvashidze, or Chachba).

Abkhazia within the Russian Empire and Soviet Union

The expansion of the Russian Empire into the Caucasus region led to small-scale but regular conflicts between Russian colonists and the indigenous Caucasian tribes. Eventually the Caucasian War erupted, which ended with Russian conquest of the North and Western Caucasus. Various Georgian principalities were annexed to the empire between 1801 and 1864. The Russians acquired possession of Abhkazia in a piecemeal fashion between 1829 and 1842; but their power was not firmly established until 1864, when they managed to abolish the local principality which was still under Shervashidze rule. Large numbers of Muslim Abkhazians — said to have constituted as much as 60% of the Abkhazian population, although contemporary census reports were not very trustworthy — emigrated to the Ottoman Empire between 1864 and 1878 together with other Muslim population of Caucasus in the process known as Muhajirism.

Modern Abkhazian historians maintain that large areas of the region were left uninhabited, and that many Armenians, Georgians and Russians (all Christians) subsequently migrated to Abkhazia, resettling much of the vacated territory. This version of events is strongly contested by some Georgian historians[23] who argue that Georgian tribes (Mingrelians and Svans) had populated Abkhazia since the time of the Colchis kingdom. According to Georgian scholars, the Abkhaz are the descendants of North Caucasian tribes (Adygey, Apsua), who migrated to Abkhazia from the north of the Caucasus Mountains and merged there with the existing Georgian population.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 led to the creation of an independent Georgia (which included Abkhazia) in 1918. Georgia's Menshevik government had problems with the area through most of its existence despite a limited autonomy being granted to the region. In 1921, the Bolshevik Red Army invaded Georgia and ended its short-lived independence. Abkhazia was made a Soviet republic with the ambiguous status of Union Republic associated with the Georgian SSR, In 1931, Stalin made it an autonomous republic within Soviet Georgia. Despite its nominal autonomy, it was subjected to strong central rule from central Soviet authorities. Georgian became the official language. Purportedly, Lavrenty Beria encouraged Georgian migration to Abkhazia, and many took up the offer and resettled there. Russians also moved into Abkhazia in great numbers. Later, in the 1950s and 1960s, Vazgen I and the Armenian church encouraged and funded the migration of Armenians to Abkhazia. Currently, Armenians are the largest minority group in Abkhazia.

The repression of the Abkhaz was ended after Stalin's death and Beria's execution, and Abkhaz were given a greater role in the governance of the republic. As in most of the smaller autonomous republics, the Soviet government encouraged the development of culture and particularly of literature. Ethnic quotas were established for certain bureaucratic posts, giving the Abkhaz a degree of political power that was disproportionate to their minority status in the republic. This was interpreted by some as a "divide and rule" policy whereby local elites were given a share in power in exchange for support for the Soviet regime. In Abkhazia as elsewhere, it led to other ethnic groups - in this case, the Georgians - resenting what they saw as unfair discrimination, thereby stoking ethnic discord in the republic.

The Abkhazian War

As the Soviet Union began to disintegrate at the end of the 1980s, ethnic tensions grew between the Abkhaz and Georgians over Georgia's moves towards independence. Many Abkhaz opposed this, fearing that an independent Georgia would lead to the elimination of their autonomy, and argued instead for the establishment of Abkhazia as a separate Soviet republic in its own right. The dispute turned violent on 16 July 1989 in Sukhumi. Sixteen Georgians are said to have been killed and another 137 injured when they tried to enroll in a Georgian University instead of an Abkhaz one. After several days of violence, Soviet troops restored order in the city and blamed rival nationalist paramilitaries for provoking confrontations.

Georgia declared independence on 9 April 1991, under the rule of the former Soviet dissident Zviad Gamsakhurdia. Gamsakhurdia's rule became unpopular, and that December the Georgian National Guard, under the command of Tengiz Kitovani, laid siege to the offices of Gamsakhurdia's government in Tbilisi. After weeks of stalemate, he was forced to resign in January 1992. He was replaced as president by Eduard Shevardnadze, the former Soviet foreign minister and architect of the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Shevardnadze inherited a government dominated by hardline Georgian nationalists, and although he was not an ethnic nationalist, he did little to avoid being seen as supporting the government figures and powerful coup leaders who were.

On 21 February 1992, Georgia's ruling Military Council announced that it was abolishing the Soviet-era constitution and restoring the 1921 Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Georgia. Many Abkhaz interpreted this as an abolition of their autonomous status. In response, on 23 July 1992, the Abkhazia government effectively declared secession from Georgia, although this gesture went unrecognised by any other country. The Georgian government accused Gamsakhurdia supporters of kidnapping Georgia's interior minister and holding him captive in Abkhazia. The Georgian government dispatched 3,000 troops to the region, ostensibly to restore order. Heavy fighting between Georgian forces and Abkhazian militia broke out in and around Sukhumi. The Abkhazian authorities rejected the government's claims, claiming that it was merely a pretext for an invasion. After about a week's fighting and many casualties on both sides, Georgian government forces managed to take control of most of Abkhazia, and closed down the regional parliament.

The Abkhazians' military defeat was met with a hostile response by the self-styled Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus, an umbrella group uniting a number of pro-Russian movements in the North Caucasus ((Chechens, Cossacks, Ossetians and others)), Russian military units. Hundreds of volunteer paramilitaries from Russia (including the then little known Shamil Basayev) joined forces with the Abkhazian separatists to fight the Georgian government forces. Regular Russian forces also reportedly sided with the secessionsts. In September, the Abkhaz and Russian paramilitaries mounted a major offensive against Gagra after breaking a cease-fire, which drove the Georgian forces out of large swathes of the republic. Shevardnadze's government accused Russia of giving covert military support to the rebels with the aim of "detaching from Georgia its native territory and the Georgia-Russian frontier land". The year 1992 ended with the rebels in control of much of Abkhazia northwest of Sukhumi.

The conflict remained stalemated until July 1993, when the Abkhaz separatist militias launched an abortive attack on Georgian-held Sukhumi. The capital was surrounded and heavily shelled, with Shevardnadze himself trapped in the city.

Although a truce was declared at the end of July, this collapsed after a renewed Abkhaz attack in mid-September. After ten days of heavy fighting, Sukhumi fell on 27 September, 1993. Eduard Shevardnadze narrowly escaped death, having vowed to stay in the city no matter what, but he was eventually forced to flee when separatist snipers fired on the hotel where he was residing. Abkhaz, North Caucasian militants and their allies committed numerous atrocities [1] against the remaining Georgian population of the city (these events are known as Sukhumi Massacre). The mass killings and destruction continued for two weeks, leaving thousands dead and missing.

The Abkhaz forces quickly overran the rest of Abkhazia as the Georgian government faced a second threat: an uprising by the supporters of the deposed Zviad Gamsakhurdia in the region of Mingrelia (Samegrelo). In the chaotic aftermath of defeat almost all ethnic Georgians fled the region, escaping an ethnic cleansing initiated by the victors. Many thousands died — it is estimated that between 10,000-30,000 ethnic Georgians and 3,000 ethnic Abkhaz may have perished — and some 250,000 people (mostly Georgians) were forced into exile.[1][24][25]

During the war, gross human rights violations were reported on the both sides (see Human Rights Watch report[26]), and the ethnic cleansing committed by the Abkhaz forces and their allies is recognized by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Summits in Budapest (1994)[27], Lisbon (1996)[28] and Istanbul (1999)[29]

De jure Government of Abkhazia

The de jure Government of Abkhazia is the only body internationally recognized as a legal authority of Abkhazia, which controls only the north-eastern part of Abkhazia and is located in Chkhalta, Upper Abkhazia. The de jure Government of Abkhazia, then the Council of Ministers of Abkhazia, left Abkhazia after the Russian-backed Abkhaz separatist forces and their allies stormed Sukhumi on September 27, 1993 and expelled the majority of its Georgian residents and members of the Government. For about 13 years, the Government was known as the Government of Abkhazia in exile and was located in Tbilisi until the 2006 Kodori crisis, which reinstalled the Government back within the administrative borders of Abkhazia. Malkhaz Akishbaia, a Western-educated Abkhaz politician was elected in April 2006 and is the current head of the de jure Government of Abkhazia. On September 27, 2006 President Mikheil Saakashvili, Nino Burjanadze, Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia Ilia II and others members of the central government visited Kodory Valley and officially changed the name and designated the area as "Upper Abkhazia". President Saakashvili addressed the nation during the opening of de jure Government headquarters in Chkhalta, Upper Abkhazia:

- "We are here – Upper Abkhazia, very close to Sokhumi - and we are not going to leave this place. We will return to Abkhazia very soon, but only through peaceful means." “...We have told every foreign ambassador in Georgia that Abkhazia and Tbilisi are not separate entities… From now on the protocol of each foreign diplomat [visiting Abkhazia], apart from trips to Sokhumi, will also include the route to Abkhazia’s administrative center in the village of Chkhalta where the chairman of the Abkhaz government is Malkhaz Akishbaia."[30]

Politics

Much of the Politics in Abkhazia is dominated by the territorial dispute with Georgia, from which the territory seceded, and by the fight over the presidency in 2004/2005.

On 3 October 2004 presidential elections were held in Abkhazia. In the elections, Russia evidently supported Raul Khajimba, the prime minister backed by seriously ailing outgoing separatist President Vladislav Ardzinba. Posters of Russia's President Vladimir Putin together with Khajimba, who like Putin had worked as a KGB official, were everywhere in Sukhumi. Deputies of Russia's parliament and Russian singers, lead by Joseph Kobzon, a deputy and a popular singer, came to Abkhazia campaigning for Khajimba.

However Raul Khajimba lost the elections to Sergey Bagapsh. The tense situation in the republic led to the cancellation of the election results by the Supreme Court. After that the deal was struck between former rivals to run jointly — Bagapsh as a presidential candidate and Khajimba as a vice presidential candidate. They received more than 90% of the votes in the new election.

The People's Assembly consisting of 35 elected members is vested with legislative powers. The last parliamentary elections were held on March 4, 2007.

About 250,000 ethnic Georgian residents of Abkhazia are restricted form entering the region by the Abkhazian separatist regime and cannot participate in the elections.[citation needed]

International involvement

The UN has played various roles during the conflict and peace process: a military role through its observer mission (UNOMIG); dual diplomatic roles through the Security Council and the appointment of a Special Envoy, succeeded by a Special Representative to the Secretary-General; a humanitarian role (UNHCR and UNOCHA); a development role (UNDP); a human rights role (UNCHR); and a low-key capacity and confidence-building role (UNV). The UN’s position has been that there will be no forcible change in international borders. Any settlement must be freely negotiated and based on autonomy for Abkhazia legitimized by referendum under international observation once the multi-ethnic population has returned.[31] According to Western interpretations the intervention did not contravene international law since Georgia, as a sovereign state, had the right to secure order on its territory and protect its territorial integrity.

OSCE has increasingly engaged in dialogue with officials and civil society representatives in Abkhazia, especially from NGOs and the media, regarding human dimension standards and is considering a presence in Gali. OSCE expressed concern and condemnation over ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia during the 1994 Budapest Summit Decision[32] and later at the Lisbon Summit Declaration in 1996.[33]

The USA rejects the unilateral secession of Abkhazia and urges its integration into Georgia as an autonomous unit. In 1998 the USA announced its readiness to allocate up to $15 million for rehabilitation of infrastructure in the Gali region if substantial progress is made in the peace process. USAID has already funded some humanitarian initiatives for Abkhazia. The USA has in recent years significantly increased its military support to the Georgian armed forces but has stated that it would not condone any moves towards peace enforcement in Abkhazia.

On August 22, 2006, Senator Richard Lugar, then visiting Georgia's capital Tbilisi, joined the Georgian politicians in criticism of the Russian peacekeeping mission, stating that "the U.S. administration supports the Georgian government’s insistence on the withdrawal of Russian peacekeepers from the conflict zones in Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali district."[34]

On October 5, 2006, Javier Solana, the High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy of the European Union, ruled out the possibility of replacing the Russian peacekeepers with the EU force."[35] However, the Georgian parliament is preparing for the vote in October of 2006 which will demand the complete withdrawal of Russian peacekeepers from Abkhazia.[36] On October 10, 2006, EU South Caucasus envoy Peter Semneby noted that "Russia's actions in the Georgia spy row have damaged its credibility as a neutral peacekeeper in the EU's Black Sea neighbourhood."[37]

On October 13, 2006, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted a resolution, based on a Group of Friends of the Secretary-General draft, extending the UNOMIG mission until April 15, 2007. Acknowledging that the "new and tense situation" resulted, at least in part, from the Georgian special forces operation in the upper Kodori Valley, urged the country to ensure that no troops unauthorized by the Moscow ceasefire agreement were present in that area. It urged the leadership of the Abkhaz side to address seriously the need for a dignified, secure return of refugees and internally displaced persons and to reassure the local population in the Gali district that their residency rights and identity will be respected. The Georgian side is "once again urged to address seriously legitimate Abkhaz security concerns, to avoid steps which could be seen as threatening and to refrain from militant rhetoric and provocative actions, especially in upper Kodori Valley". Calling on both parties to follow up on dialogue initiatives, it further urged them to comply fully with all previous agreements regarding non-violence and confidence-building, in particular those concerning the separation of forces. Regarding the disputed role of the peacekeepers from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Council stressed the importance of close, effective cooperation between UNOMIG and that force and looked to all sides to continue to extend the necessary cooperation to them. At the same time, the document reaffirmed the "commitment of all Member States to the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Georgia within its internationally recognized borders."[38]

Gallery of Abkhazia

This section contains an unencyclopedic or excessive gallery of images. |

-

Pitsunda Cathedral

-

New Athos Railway Station

-

New Athos monastery

-

Ritsa lake

-

Gagra

-

Geg waterfall

-

View of Sukhumi 1

-

View of Sukhumi 2

-

View from Pitsunda cape

-

Sukhumi quay

-

Sukhumi botanical garden front entrance

-

Chanba Dramatic theatre in Sukhumi

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Full Report by Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch. Georgia/Abkhazia. Violations of the laws of war and Russia's role in the conflict Helsinki, March 1995

- ^ Chervonnaia, Svetlana Mikhailovna. Conflict in the Caucasus: Georgia, Abkhazia, and the Russian Shadow. Gothic Image Publications, 1994.

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6216822.stm

- ^ Amy McCallio, Rise of Abkhaz Separatism, YATT Publications, 2004.

- ^ http://mosnews.com/news/2006/07/21/luzhkabkhaz.shtml

- ^ http://www.geotimes.ge/index.php?m=home&newsid=2810

- ^ Breakaway Abkhazia seeks recognition, Al-Jazeera, October 18, 2006.

- ^ Abkhazia: Ways Forward, Europe Report N°179 , 18 January 2007

- ^ UN High Commissioner for refugees. Background note on the Protection of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Georgia remaining outside Georgia, [1]

- ^ Report of the Representative of the Secretary-General on the human rights of internally displaced persons – Mission to Georgia. United Nations: 2006.

- ^ Georgia-Abkhazia: Profiles. Accord: an international review of peace initiatives. Reconciliation Resources. Accessed on April 2, 2007.

- ^ Абхазская компания в 2007 году начнет добычу стройматериалов на Псоу, Official web-site of the President of the Abkhaz Republic, December 21, 2006.

- ^ Cornell, Svante E. (2001), Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, p. 156. Routledge (UK), ISBN 0700711627)

- ^ Müller, D, 1999. Demography: ethno-demographic history, 1886-1989 in The Abkhazians: A handbook. Richmond: Curzon Press.

- ^ Ментешашвили А.М. Исторические предпосылки современного сепаратизма в Грузии. - Тбилиси, 1998. [2]

- ^ JRL RESEARCH & ANALYTICAL SUPPLEMENT ~ JRL 8226, Issue No. 24 • May 2004. SPECIAL ISSUE; THE GEORGIAN-ABKHAZ CONFLICT: PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE

- ^ 1-я Всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Кутаисская губерния. Спб: 1905. С. 32

- ^ Sukhum, Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedia

- ^ [3] 2003 Census statistics Template:Ru icon

- ^ The International Crisis Group. Abkhazia Today. Europe Report N°176, p. 9. 15 September 2006.

- ^ "Georgia." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 30 Apr. 2007.

- ^ http://www.statistics.ge/Main/Yearbook/2005/05Population_05.doc Statistical Yearbook of Georgia, 2005: Population] (607kb, Microsoft Word Document). The State Department of Statistics of Georgia. Retrieved on April 30, 2007.

- ^ Lortkipanidze M., The Abkhazians and Abkhazia, Tbilisi 1990.

- ^ Chervonnaia, Svetlana Mikhailovna. Conflict in the Caucasus: Georgia, Abkhazia, and the Russian Shadow. Gothic Image Publications, 1994, Intruduction

- ^ Human Rights Watch Helsinki. Georgia; Human Rights Developments http://www.hrw.org/reports/1996/WR96/Helsinki-09.htm

- ^ Georgia/Abkhazia. Violations of the laws of war and Russia's role in the conflict" http://www.hrw.org/reports/1995/Georgia2.htm

- ^ [http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/osce/new/Regional-Issues.html CSCE Budapest Document 1994, Budapest Decisions, Regional Issues]

- ^ Lisbon OSCE Summit Declaration

- ^ Istanbul OSCE Summit Declaration

- ^ http://civil.ge/eng/detail.php?id=13654

- ^ Resolutions 849, 854, 858, 876, 881 and 892 adopted by the UN Security Council

- ^ From the Resolution of the OSCE Budapest Summit, 6 December 1994 [4]

- ^ Lisbon Summit Declaration of the OSCE, 2-3 December 1996

- ^ U.S. Senator Urges Russian Peacekeepers’ Withdrawal From Georgian Breakaway Republics. (MosNews).

- ^ Solana fears Kosovo 'precedent' for Abkhazia, South Ossetia. (International Relations and Security Network).

- ^ http://civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=13827

- ^ Russia 'not neutral' in Black Sea conflict, EU says, EUobserver, October 10, 2006.

- ^ SECURITY COUNCIL EXTENDS GEORGIA MISSION UNTIL 15 APRIL 2007, The UN Department of Public Information, October 13, 2006.

External links

- Template:En icon/Template:Ru icon/Template:Ab icon President of the Republic of Abkhazia. Official site

- Template:En icon/Template:Ru icon Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Abkhazia. Official Site

- Template:En icon BBC Regions and territories: Abkhazia

- Template:En icon The Autonomous Republic of Abkhazeti - from Georgian National Parliamentary Library

- Template:En icon Abkhazia.com Official website of the refugees from Abkhazia

- Template:Ru icon Abkhazian news

- Template:Ru icon State Information Agency of the Abkhaz Republic

- Template:En icon Abkhazia Provisional Paper Money

- Template:Ru icon Orthodox Churches of Abkhazia

- Template:Ru icon Archaeology and ethnography of Abkhazia. Abkhaz Institute of Social Studies. Abkhaz State Museum