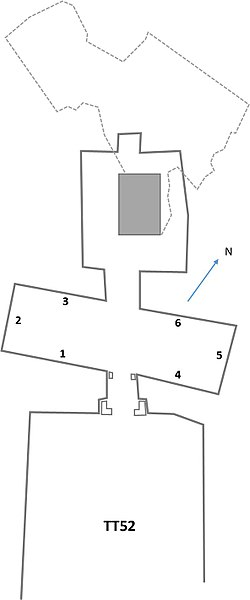

TT52

| TT52 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of Nakht | |

Plan of TT52 | |

| Coordinates | 25°43′54.65″N 32°36′35.84″E / 25.7318472°N 32.6099556°E |

| Location | Sheikh Abd el-Qurna |

← Previous TT51 Next → TT53 | |

The Theban Tomb TT52 is located in Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, part of the Theban Necropolis, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite to Luxor. It is the burial place of Nakht, an ancient Egyptian official who held the position of a scribe and astronomer of Amun, probably during the reign of Thutmose IV (1401–1391 BC or 1397–1388 BC) during the Eighteenth Dynasty, the first dynasty of the New Kingdom.[1]

Architecture

[edit]The tomb architecture and decoration conforms to the standard design of Theban tombs of the New Kingdom by using such scenes that are commonly found in contemporary tombs. Some of these decorations display differences from scenes found in Old Kingdom mastabas of Memphis, where one of the principal functions of the tomb was to ensure magical sustenance for the ka, whereas in the New Kingdom tombs, the primary function was to identify oneself on the tomb walls.

The tomb has the typical T-shaped architectural design that was common for non-royal Theban tombs of the New Kingdom; there was a broad hall, which followed from the entrance and court. This led into an inner chamber, the long hall, and the shrine, which was situated in a niche, containing the statue of the deceased. These chambers were designed to contain scenes for the service of the dead in their afterlife. Essentially, this architectural design is somewhat similar to that of the bipartite mastabas of the Old Kingdom, which contained two main chambers, the offering chapel and the burial chamber, as these New Kingdom tombs also contain two main chambers. However, in the latter tombs both of the chambers are created for different purposes to that of the chambers within the Old Kingdom mastabas. Within the mastaba, the offering chapel was dedicated to the sustenance of the deceased beyond death by magically providing food and water. Such scenes are generally not depicted as often in the New Kingdom tombs.

Decoration

[edit]| Nakht in hieroglyphs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| |||

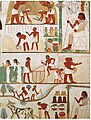

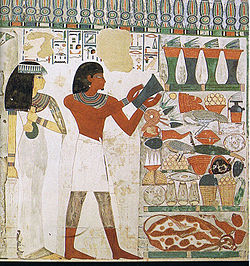

The stela on the south wall of the broad hall shows men making offerings to images of the deceased. Beneath this, Nut is shown before a pile of offerings. This scene, therefore, shows that the dead were not wholly reliant on their family for offerings but could rely on "a divine source as well".[3] Similar scenes could also be found on the walls of Old Kingdom burials, depicting processions of people bringing offerings for the deceased. However, Malek wrote that offerings scenes are rarer in New Kingdom tombs than in the Old Kingdom.[4]

Two corresponding scenes are depicted on the east wall next to the entrance to the broad hall. These scenes show Nakht and his wife, Tawy, making offerings to Ra, who is manifested by the sunlight that would emerge from the doorway. This scene is depicted to show the continuation of an earthly ritual in the afterlife[3] – in the New Kingdom private individuals had access to an afterlife meaning that they could expect to enter the Field of Reeds.

A scene on the south side of the west wall represents a banquet scene. This genre of scene is frequently represented in New Kingdom tombs. The family of the deceased, in this case Nakht and Tawy, is also shown together being entertained by the musicians and dancers. Malek[4] wrote "domestic scenes are frequent" because they emphasise the closeness of the family and their continued existence together in the afterlife. However, these scenes may also have a sexual or potent purpose for the afterlife. Mannich[5] wrote that by including such scenes in the tomb, the deceased could be guaranteed potency in the hereafter. She writes that banquet scenes "are littered with such references" including the inclusion of mandrakes and lotus flowers, which are being held by the women in the second register. These type of scenes were highly common in New Kingdom Theban tombs.

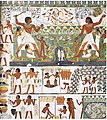

On the south side of the east wall, there is an agricultural scene. Nakht is shown overseeing men who are ploughing, sowing and harvesting the fields. The scenes of agriculture may show the continuation of Nakht’s life in the Field of Reeds. However, as suggested by Noblecourt, these scenes may metaphorically show an eternal life through the process of farming, through the seasons.[5] If Noblecourt’s view is accurate, then the scenes are different from that of Old Kingdom mastabas, where any agricultural scenes were designed primarily as a means of magically ensuring the continuity of farming on the estates of the deceased, thereby allowing sustenance for their ka.

On the north side of the west wall, Nakht is shown in a further frequently depicted scene: the fishing and fowling scene. This type of scene is also commonly found in New Kingdom, and although they were not uncommon in Old Kingdom mastabas, within the latter their primary purpose was to provide magical sustenance for the dead. In the tomb of Nakht, he is shown spearing fish and fowl, together with his family. Davies (1917:66) suggests that "sustenance…was not always coaxed from the soil by severe labor [sic]", indicating that this scene was used to show a form of receiving food after death in a different way, for entertainment for the deceased and for an artistic change of genre. However, there is a different interpretation that they were, like banquet scenes, depicted to show an image of potency and creativity after death as some of the equipment is similar and "the women present…wear outfits similar to that worn for a banquet".[5]

Davies[3] writes that all of these scenes may have had a further important motif in showing the family of the deceased together. He wrote that the Egyptians enjoyed family life and "the strength with which love of family survived death is witnessed to by the family groups painted on nearly every wall", suggesting that one purpose of the tomb scenes was to guarantee their company beyond death.

The architecture and decoration display much evidence for the thought of the Egyptians regarding their afterlife. As the tomb was split into two chambers, it can be said that they regarded their death in two parts, their afterlife and the transition phase between death and the afterlife, the latter not being depicted in the Tomb of Nakht. The decoration shows that, in contrast to Old Kingdom beliefs, as depicted of the walls of Memphite mastabas, its most important function was depict a life after death, together with family, with indications of creativity and potency, and "thus the picture of Theban life in a tomb of the Eighteenth Dynasty is a clear mirror of existence…of the homesteads around it where the nature-loving Egyptian preferred to dwell".[3]

-

Famous painting of the Beautiful festival of the valley

-

Nakht shown hunting and fishing (above); the production of wine (below)

-

A false door surrounded by various depictions of offerings

-

A painting depicting an agricultural scene

-

Tawy embracing Nakht as he smells a lotus, whilst they sit together before a set of offerings

-

Entrance to the Tomb of Nakht

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Baikie, James (1932). Egyptian Antiquities in the Nile Valley. Methuen.

- ^ Porter, Bertha and Moss, Rosalind, Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings Volume I: The Theban Necropolis, Part I. Private Tombs, Griffith Institute. 1970 ASIN B002WL4ON4, pp. 99–102

- ^ a b c d Norman de Garis Davies, The Tomb of Nakht at Thebes, Robb de Peyster Tytus Memorial Series, Volume 1, Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1917

- ^ a b Malek, Jaromir: Egyptian Art, Phaidon Press Limited, New York, 1999, reprinted 2002, pp. 240, 243

- ^ a b c Manniche, Lise: The so-called scenes of daily life in the private tombs of the Eighteenth Dynasty from Strudwick, Nigel and Taylor, John, The Theban Necropolis: Past Present and Future, The British Museum Press, London, 2002

External links

[edit]- Nakht – TT52 from Osirisnet.