Abanindranath Tagore

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2015) |

শিল্পাচার্য - Great Teacher of the Arts Abanindranath Tagore অবনীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর | |

|---|---|

Abanindranath Tagore | |

| Born | Jorasanko 7 August 1871 |

| Died | 5 December 1951 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | India |

| Known for | Drawing, painting, writing |

| Notable work | Bharat Mata; The Passing of Shah Jahan; Bageshwari shilpa-prabandhabali; Bharatshilpe Murti; Buro Angla; Jorasankor Dhare; Khirer Putul; Shakuntala |

| Movement | Bengal school of art, Contextual Modernism |

| Awards | honorary doctor of the University of Calcutta

|

Abanindranath Tagore CIE (Bengali: অবনীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর; 7 August 1871 – 5 December 1951) was the principal artist and creator of the Indian Society of Oriental Art in 1907. He was also the first major exponent of Swadeshi values in Indian art. He founded the influential Bengal school of art, which led to the development of modern Indian painting.[1][2] He was also a noted writer, particularly for children. Popularly known as 'Aban Thakur', his books Rajkahini, Buro Angla, Nalak, and Khirer Putul were landmarks in Bengali language children's literature and art.

Tagore sought to modernise Mughal and Rajput styles to counter the influence of Western models of art, as taught in art schools under the British Raj. Along with other artists from the Bengal school of art, Tagore advocated in favour of a nationalistic Indian art derived from Indian art history, drawing inspiration from the Ajanta Caves. Tagore's work was so successful that it was eventually accepted and promoted as a national Indian style within British art institutions.[3]

Personal life and background

[edit]Abanindranath Tagore was born in Jorasanko, Calcutta, British India, to Gunendranath Tagore and Saudamini Devi. His grandfather was Girindranath Tagore, the second son of "Prince" Dwarkanath Tagore. He was a member of the distinguished Tagore family and a nephew of the poet Rabindranath Tagore. His grandfather and his elder brother, Gaganendranath Tagore, were also artists.

Tagore learned art while studying at Sanskrit College, Kolkata in the 1880s.

In 1890, Tagore attended the Calcutta School of Art where he learnt to use pastels from O. Ghilardi, and oil painting from C. Palmer, European painters who taught in that institution.[4]

In 1888, he married Suhasini Devi, daughter of Bhujagendra Bhusan Chatterjee, a descendant of Prasanna Coomar Tagore. He left Sanskrit College after nine years of study and studied English as a special student at St. Xavier's College, which he attended for about a year and a half.

He had a sister, Sunayani Devi, who was also a painter.[5] Her paintings depicted both mythological and domestic scenes, some of which were inspired by Patachitra.[6]

Painting career

[edit]

Early life

[edit]In the early 1890s several of his illustrations were published in Sadhana magazine, and in Chitrangada, and other works by Rabindranath Tagore. He also illustrated his own books. Around 1897 he took lessons from the vice-principal of the Government School of Art, studying in the traditional European academic manner, learning the full range of techniques, but with a particular interest in watercolour. It was during this period that he developed his interest in Mughal art, producing a number of works based on the life of Krishna in a Mughal-influenced style. After meeting E. B. Havell, Tagore worked with him to revitalise and redefine teaching of art at the Calcutta School of Art, a project also supported by his brother Gaganendranath, who set up the Indian Society of Oriental Art.

Tagore believed in the traditional Indian techniques of painting. His philosophy rejected the "materialistic" art of the West and came back to Indian traditional art forms. He was influenced by the Mughal school of painting as well as Whistler's Aestheticism. In his later works, Tagore started integrating Chinese and Japanese calligraphic traditions into his style.

Later career

[edit]He believed that Western art was "materialistic" in character, and that India needed to return to its own traditions to recover its spiritual values. Despite its Indo-centric nationalism, this view was already commonplace within British art of the time, stemming from the ideas of the Pre-Raphaelites.[7] Tagore's work also shows the influence of Whistler's Aestheticism. Partly for this reason many British arts administrators were sympathetic to such ideas, especially as Hindu philosophy was becoming increasingly influential in the West following the spread of the Theosophy movement. Tagore believed that Indian traditions could be adapted to express these new values, and to promote a progressive Indian national culture.

His finest achievement was the Arabian Nights series which was painted in 1930. In these paintings he uses the Arabian Nights stories as a means of looking at colonial Calcutta and picturing its emergent cosmopolitanism.[8][9]

With the success of Tagore's ideas, he came into contact with other Asian cultural figures, such as the Japanese art historian Okakura Kakuzō and the Japanese painter Yokoyama Taikan, whose work was comparable to his own. In his later work, he began to incorporate elements of Chinese and Japanese calligraphic traditions into his art, seeking to construct a model for a modern pan-Asian artistic tradition which would merge the common aspects of Eastern spiritual and artistic cultures.[10]

His close students included Nandalal Bose, Samarendranath Gupta, Kshitindranath Majumdar, Surendranath Ganguly, Asit Kumar Haldar, Sarada Ukil, Kalipada Ghoshal, Manishi Dey, Mukul Dey, K. Venkatappa and Ranada Ukil.

For Tagore, the house he grew up in (5 Dwarakanath Tagore Lane) and its companion house (6 Dwarakanath Tagore Lane) connected two cultural worlds – 'white town' (where the British colonisers lived) and 'black town' (where the natives lived). According to architectural historian Swati Chattopadhay, Tagore used the Bengali meaning of the word, Jorasanko ('double bridge') to develop this idea in the form of a mythical map of the city. The map was, indeed, not of Calcutta, but an imaginary city, Halisahar, and was the central guide in a children's story Putur Boi (Putu's Book). The nineteenth-century place names of Calcutta, however, appear on this map, thus suggesting that this imaginary city be read with the colonial city as a frame of reference. The map used the structure of a board game (golokdham) and showed a city divided along a main artery; on one side a lion-gate leads to the Lal-Dighi in the middle of which is the 'white island.'[11]

Tagore maintained throughout his life a long friendship with the London-based artist, author and eventual president of London's Royal College of Art, William Rothenstein. Arriving in the autumn of 1910, Rothenstein spent almost a year surveying India's cultural and religious sites, including the ancient Buddhist caves of Ajanta; the Jain carvings of Gwalior; and the Hindu panoply of Benares. He ended up in Calcutta, where he drew and painted with Tagore and his students, attempting to absorb elements of Bengal School style into his own practice.[12]

However limited Rothenstein's experiments with the styles of early Modernist Indian painting were, the friendship between him and Abanindranath Tagore ushered in a crucial cultural event. This was Rabindranath Tagore's time living at Rothenstein's London home, which led to the publication of the English-language version of Gitanjali and the subsequent award to Rabindranath in 1913 of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The publication of Rabindranath Tagore's Gitanjali in English brought the Tagore family international renown, which helped to make Abanindranath Tagore's artistic projects better known in the West.

Abanindranath Tagore became chancellor of Visva Bharati in 1942.[13]

Rediscovery

[edit]Within a few years of the artist's death in 1951, his eldest son, Alokendranath, bequeathed almost the entire family collection of Abanindranath Tagore's paintings to the newly founded Rabindra Bharati Society Trust that took up residence on the site of their famous house on No. 5, Dwarakanath Tagore lane. As only a small number of the artist's paintings had been collected or given away in his lifetime, the Rabindra Bharati Society became the main repository of Tagore's works throughout his life. Banished into trunks inside the dark offices of the society, these paintings have remained in permanent storage ever since. As a result, the full range and brilliance of Tagore's works has never be effectively projected into the public domain. They remained intimately known only to a tiny circle of art connoisseurs and scholars in Bengal, some of whom like K. G. Subramanyan and R. Siva Kumar have long argued that the true measure of Tagore's talent is to be found in his works of the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s but could do little to offer up a comprehensive profile of the master for the contemporary art world.

R. Siva Kumar's Paintings of Abanindranath Tagore (2008) is a path-breaking book redefining Tagore's art. Another book that constitutes a serious reconsideration of Tagore's art, contextualising it as a critique of modernity and the nation-state is Debashish Banerji's The Alternate Nation of Abanindranath Tagore (2010).[14]

Indian film director Purnendu Pattrea made a documentary film on the artist, titled Abanindranath, in 1976.[15]

List of paintings

[edit]A list of paintings by Abanindranath Tagore:[16]

- Ashoka's Queen (1910)

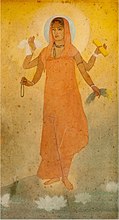

- Bharat Mata (1905)

- Fairyland Illustration (1913)

- Ganesh Janani (1908)

- Aurangzeb examining the head of Dara Shikoh (1911)

- Avisarika (1892)

- Baba Ganesh (1937)

- Banished Yaksha (1904)

- Yay and Yay (1915)

- Buddha and Sujata (1901)

- Chaitanya with his followers on the sea beach of Puri (1915)

- End of Dalliance (1939)

- Illustrations of Omar Khayyam (1909)

- Kacha and Devajani (1908)

- Krishna Lal series (1901 to 1903)

- Moonlight Music Party (1906)

- Moonrise at Mussouri Hills (1916)

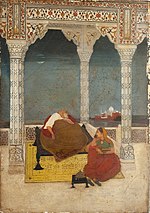

- Passing of Shah Jahan (1900)

- Poet's Baul-dance in Falgurni (1916)

- Pushpa-Radha (1912)

- Radhika gazing at the portrait of Sri Krishna (1913)

- Shah Jahan Dreaming of Taj (1909)

- Sri Radha by the River Jamuna (1913)

- Summer, from Ritu Sanghar of Kalidasa (1905)

- Tales of Arabian Nights (1928)

- Temple Dancer (1912)

- The Call of the Flute (1910)

- The Feast of Lamps (1907)

- Journey's End (1913)

- Veena Player (1911)

- Jatugriha Daha (1912)

Family tree

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

Bharat Mata (c. 1905)

-

The Passing of Shah Jahan (1902)

-

My Mother (1912–13)

-

Fairyland illustration (1913)

-

Journey's End (c. 1913)

-

The Final Release, from the book Buddha and the gospel of Buddhism (1916), by Ananda Coomaraswamy

References

[edit]- ^ John Onians (2004). "Bengal School". Atlas of World Art. Laurence King Publishing. p. 304. ISBN 1856693775.

- ^ Abanindranath Tagore, A Survey of the Master’s Life and Work by Mukul Dey Archived 4 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine, reprinted from "Abanindra Number," The Visva-Bharati Quarterly, May – Oct. 1942.

- ^ The International Studio, Vol. 35: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art: Jul-Oct 1908. Forgotten Books. pp. 107–116, E.B. Havell. ISBN 9781334345050.

- ^ Chaitanya, Krishna (1994). A history of Indian painting: the modern period. Abhinav Publications. p. 145. ISBN 978-81-7017-310-6.

- ^ "All Those Good Years". Express India. Archived from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- ^ Das, Dattatraya (22 January 2024). "Chokher Bali: Tagore's literary women and his kinswomen". Celebrating Tagore - The Man, The Poet and The Musician. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

- ^ Guha-Thakurta, Tapati (1992). The making of a new "Indian" art : artists, aesthetics, and nationalism in Bengal, c. 1850-1920. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. pp. 147–179. ISBN 9780521392471.

- ^ Siva Kumar, R. (2008). Paintings of Abanindranath Tagore. Pratikshan Books. p. 384. ISBN 978-81-89323-09-7. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014.

- ^ Banerji, Debashish (2010). The Alternate Nation of Abanindranath Tagore. New Delhi: SAGE. pp. 85–108. ISBN 9788132102397. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Video of a London University Lecture detailing Abanindranath's Importance to Global Modernism, London University School of Advanced Study, March 2012.

- ^ Swati Chattopadhyay, Representing Calcutta: Modernity, Nationalism, and the Colonial Uncanny. Routledge 2006.

- ^ Rupert Richard Arrowsmith, "An Indian Renascence and the rise of global modernism: William Rothenstein in India, 1910–11", The Burlington Magazine, vol.152 no.1285 (April 2010), pp.228–235.

- ^ Samsad Bangali Charitabhidhan (Biographical Dictionary), Chief Editor: Subodh Chandra Sengupta, Editor: Anjali Bose, 4th edition 1998, (in Bengali), Vol I, page 23, ISBN 81-85626-65-0, Sishu Sahitya Samsad Pvt. Ltd., 32A Acharya Prafulla Chandra Road, Kolkata.

- ^ Romain, Julie. "Book Review for The Alternate Nation of Abanindranath Tagore". caa.reviews. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "ABANINDRANATH - Film / Movie". Complete Index To World Film.

- ^ Unattributed. "Abanindranath Tagore Biography". iloveindia.net. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Abanindranath Tagore at the Internet Archive

- Biography (Calcuttaweb.com)

- Mukul Dey Archives, Santiniketan, India

- Dolls by Abanindranath Tagore

- Abanindranath Tagore's Profile

- Abanindranath Tagore's Artist Profile

- Abanindranath's complete literary works in Bengali.

- Govt of India official website on paintings of Abanindranath Tagore

- Celebrating Tagore

- Indian male painters

- 1951 deaths

- Bengali Hindus

- Artists from Kolkata

- The Sanskrit College and University alumni

- Government College of Art & Craft alumni

- University of Calcutta alumni

- Academic staff of the University of Calcutta

- Tagore family

- Companions of the Order of the Indian Empire

- Bengali-language writers

- Indian children's writers

- Indian arts administrators

- Indian portrait painters

- 20th-century Indian painters

- 20th-century Indian novelists

- 1871 births

- 20th-century Indian male writers

- Painters from West Bengal

- Novelists from West Bengal

- Writers from Kolkata

- Buddhist artists

- 20th-century Indian male artists

- Artists from British India

- Writers from British India