American Veterans Committee (1943–2008)

The American Veterans Committee was founded in 1943 as a liberal veterans organization and an alternative to groups such as the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, which supported a conservative political and social agenda.[1] The organization's roots were planted in 1942 when Sgt. Gilbert Harrison began to correspond with fellow servicemen concerning an organization that expanded beyond the needs of military men. In 1943, the University Religious Conference at UCLA became a meeting place for the military men who shared this desire for a veterans organization that also advocated peace and justice. One year later in 1944, Charles Bolte joined the UCLA group and the American Veterans Committee was born. The founding group included Donald Prell. The new organization immediately began to publish the AVC Bulletin to document the organization's advocacy issues.[2]

| Formation | 1943 |

|---|---|

| Membership | 100,000 (1947)[3] |

With a motto of "Citizens First, Veterans Second," the AVC supported a range of liberal causes. Most notably, the organization challenged segregationist policy and maintained racially integrated chapters in Southern states before the era of civil rights.[3] It also played an integral role in establishing the World Veterans Federation in 1950, which still advocates the building of peace among former adversaries. While other veterans' organizations lobbied for financial "bonuses" for returning veterans, the AVC opposed such bonuses, supporting instead housing and education programs for veterans.[4] Unlike other veterans' groups, the AVC offered full membership to women and people of color.[5]

During its early years, AVC grew at exponential rates: 5,500 members in 1945, 18,000 members in 1946, and 100,000 members in 1947. However, there was a drastic drop in membership after the organization became embroiled in the Second Red Scare. While American Communists had initially disdained the AVC as "Ivy Leaguers", they later reversed their policy when their members were rejected from the American Legion, and encouraged their members to join the AVC.[6] In response to the Second Red Scare campaign, AVC ejected its Communist members and closed future membership to supporters of totalitarian parties. While the organization purged itself of Communists and survived the scandal, the episode resulted in a decrease in membership from 100,000 in 1947 to 20,000 in 1948.[2]

In its smaller form, the AVC continued through 2007 to promote efforts, in the words of historian John Egerton, to "right social wrongs at home" by supporting a variety of liberal causes: civil rights, civil liberties, veterans affairs, and international affairs. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., AVC was able to frequently testify before Congress, file briefs in major court cases, and provide legal aid to minority veterans in the South.

In order to strengthen their force, the organization partnered with other organizations, such as the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, to advocate issues. AVC also created grass-roots efforts on numerous campuses in its early years. After the War, thousands of veterans flocked to universities to take advantage of their GI Bill education benefits, which laid a foundation for the AVC to create a strong on-campus presence.

Throughout its existence, the organization advocated various aspects of its core mission of civil rights and liberties. In 1960s, AVC took on the role of watchdog in military and veterans affairs that continued throughout its existence. The organization drew attention to the Draft (1966), Human Rights of the Man in Uniform (1968 and 1970), Education Problems of Returning Vietnam Veterans (1972), and National Service (1989). During the 1970s, AVC created programs to assist Vietnam veterans with less-than-honorable discharges by providing legal advice and worked with the government to create programs for minority and female veterans, to expand representation available to veterans, and to establish a Court of Veterans Appeals.[2]

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, AVC also focused their attention on the underserved women veterans. Their efforts resulted in the creation of a Women Veterans Advisory Committee at the Veterans Administration and a new department focused on the needs of women veterans.

In the 1990s there was a shift in focus to the veterans returning from the Gulf War, national service, and equality for gays in the military.

The last two chapters closed in 2007 and 2008. These were the Washington D.C. chapter, and the Chicago area chapter led by Jerry Knight of Park Forest, IL.[3]

Notable members

[edit]

- Charles L. Bolte (1895–1989), general, US Army

- Evans Carlson (1896–1947), brigadier general, USMC[7]

- Medgar Evers (1925–1963), civil rights activist[8]

- Merle Hansen (1919–2009), activist[9]

- Gilbert A. Harrison (1915–2008), editor and owner of The New Republic

- Phineas Indritz (1916–1997), constitutional lawyer[10]

- Bentley Kassal (1917–2019), attorney, jurist, state legislator

Donald Prell wearing his WWII U.S. Army uniform in 2008 - Timothy Leary (1920–1996), psychologist, activist[3]

- Bill Mauldin (1921–2003), editorial cartoonist[3]

- Cord Meyer, Jr. (1920–2001), CIA official [1]

- William Robert Ming (1911–1973), civil rights lawyer[11]

- Donald Prell (1924-2020), author, futurist, founder of Datamation

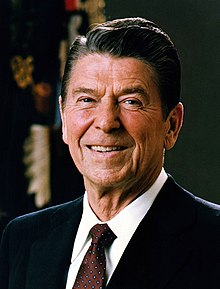

- Ronald Reagan (1911–2004), actor, U.S. president[3]

- George Reeves (1914–1959), actor[12]

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr. (1914–1988), U.S. representative [2]

- Alice Bradley Sheldon (1915–1987), science fiction writer (as James Tiptree, Jr.)[13]

- Shelby Storck (1916–1969), documentary filmmaker[14]

- Michael Straight (1916–2004), magazine publisher, novelist[15]

- Studs Terkel (1912–2008), author, oral historian[3]

- Hubert Louis Will (1914–1995), lawyer, U. S. district judge, northern district Illinois

References

[edit]- ^ Peace Campaign, Time, December 3, 1945

- ^ a b c Guide to the American Veterans Committee Records, 1942-2002, Special Collections Research Center, Estelle and Melvin Gelman Library, The George Washington University.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schmadeke, Steve, American Veterans Committee to close last chapter, based in Park Forest, Chicago Tribune, February 07, 2008

- ^ Robert Francis Saxe (2007), Settling down: World War II veterans' challenge to the postwar consensus, p. 152.

- ^ Phillips, Julie. James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2006.

- ^ March & Countermarch, Time, January 27, 1947

- ^ Marine Corps Chevron, July 14, 1945

- ^ "Medgar Evers", "NAACP History: Medgar Evers | NAACP". Archived from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- ^ Obituary, The Business Farmer, April 2, 2009 "The Business Farmer News, Opinion, Agriculture in Nebraska, Wyoming". Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved 2015-08-12.

- ^ Obituary, The Washington Post, October 18, 1997

- ^ "Ming Re-Elected Head of AMerican Veterans", Jet, May 15, 1958, p. 10.

- ^ Pasadena Veterans Will Meet Tomorrow, Metropolitan Pasadena Star-News (Pasadena, California) · 3 Mar 1946, Sun · Page 27

- ^ Phillips, 2006.

- ^ "Who is Shelby Storck" http://encycl.opentopia.com/term/Shelby_Storck Archived 2013-06-30 at archive.today

- ^ "Straight denounces current spy hunts", The Daily Californian, May 8, 1950, p. 7.