Ronald DeFeo Jr.

Ronald DeFeo Jr. | |

|---|---|

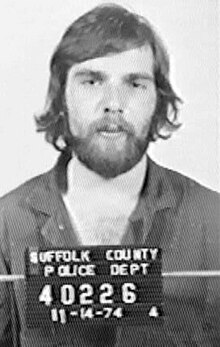

DeFeo's mug shot, November 14, 1974 | |

| Born | Ronald Joseph DeFeo Jr. September 26, 1951 Brooklyn, New York,[1] U.S. |

| Died | March 12, 2021 (aged 69) Albany, New York, U.S. |

| Other names | Butch |

| Conviction(s) | Second-degree murder (6 counts) |

| Criminal penalty | 25 years to life in prison |

| Details | |

| Date | November 13, 1974 |

| Target(s) | His family |

| Killed | 6 |

| Weapons | .35 Marlin rifle |

Ronald Joseph DeFeo Jr. (September 26, 1951 – March 12, 2021) was an American mass murderer who was tried and convicted for the 1974 killings of his father, mother, two brothers, and two sisters in Amityville, New York. Sentenced to six counts of 25 years to life, DeFeo died in prison on March 12, 2021. The case inspired the book and film versions of The Amityville Horror.[2]

Murders

[edit]Around 6:30 p.m. on November 13, 1974, DeFeo, who was then 23, entered Henry's Bar in Amityville, Long Island, New York, and declared: "You got to help me! I think my mother and father are shot!"[3] DeFeo and a small group of people went to 112 Ocean Avenue, which was located near the bar, and found that DeFeo's parents were dead inside the house. One of the group, DeFeo's friend Joe Yeswit, made an emergency call to the Amityville Police Department, who searched the house and found that six members of the family were dead in their beds.[4]

The victims were Ronald Jr.'s parents: Ronald DeFeo Sr. (43) and Louise DeFeo (née Brigante, 43); and his four siblings: Dawn (18), Allison (13), Marc (12), and John (9). All of the victims had been shot with a .35 caliber lever action Marlin 336C rifle[5] around 3:00 a.m. that day. The children had been killed by single shots, while the parents had each received two shots. Physical evidence suggests that Louise DeFeo and her daughter Allison were awake at the time of their deaths. According to Suffolk County Police, all the victims were found lying face down in bed.[6] The DeFeo family had occupied 112 Ocean Avenue since purchasing the house in 1965. The six victims were later buried in Saint Charles Cemetery nearby in Farmingdale.

Ronald DeFeo Jr., also known as "Butch", was the eldest child of the family and was its lone surviving member.[7] He was taken to the local police station for his own protection after suggesting to police officers at the scene of the crime that the killings had been carried out by a mob hitman named Louis Falini.

However, an interview at the station exposed serious inconsistencies in his version of events. The following day, he confessed to carrying out the killings himself; Falini, the alleged hitman, had an alibi proving that he was out of state at the time of the killings. DeFeo told detectives: "Once I started, I just couldn't stop. It went so fast."[3] He admitted that he had taken a bath and redressed, and detailed where he had discarded crucial evidence such as blood-stained clothes, the Marlin rifle, and cartridges, before going to work as usual.[8]

Trial and conviction

[edit]DeFeo's trial began on October 14, 1975. He and his defense lawyer, William Weber, mounted an affirmative defense of insanity, with DeFeo claiming that he had no memory of killing his family. The insanity plea was supported by the psychiatrist for the defense, Daniel Schwartz. The psychiatrist for the prosecution, Dr. Harold Zolan, maintained that, although DeFeo was a user of heroin and LSD, he had anti-social personality disorder and was aware of his actions at the time of the crime.[9] The trial's judge, Thomas Stark, declared that DeFeo's crimes were "the most heinous murders committed in Suffolk County since its founding."[10]

On November 21, 1975, DeFeo was found guilty on six counts of second-degree murder. On December 4, 1975, Judge Stark sentenced DeFeo to six sentences of 25 years to life.[11]

DeFeo was held at the Sullivan Correctional Facility in the town of Fallsburg, New York until his death, with all of his appeals and requests to the parole board being denied.[12]

Controversies

[edit]All six of the victims were found face down in their beds with no signs of a struggle. The police investigation concluded that the rifle had not been fitted with a sound suppressor and found no evidence of sedatives having been administered. DeFeo claimed during his interrogation that he had drugged his family. [13]

DeFeo had a volatile relationship with his father, but the motive for the killings remains unclear. He asked police what he had to do to collect on his father's life insurance, which prompted the prosecution to suggest at trial that his motive was to collect on the life insurance policies of his parents.[3][14][15]

After his conviction, DeFeo gave varying accounts of how the killings were carried out. In a 1986 interview for Newsday, DeFeo claimed his sister Dawn killed their father and then their distraught mother killed all of his siblings, apparently with a rifle, before he killed his mother. He stated that he took the blame because he was afraid to say anything negative about his mother to her father, Michael Brigante Sr., and his father's uncle, out of fear that they would kill him. His father's uncle was Peter DeFeo, a caporegime in the Genovese crime family. In this interview, DeFeo also asserted he was married at the time of the murders to a woman named Geraldine Gates, with whom he was living in New Jersey, and that his mother phoned to ask him to return to Amityville to break up a fight between Dawn and their father. Subsequently, he drove to Amityville with Geraldine's brother, Richard Romondoe, who was with him at the time of the murders and could verify his entire story.[16]

In 1990, DeFeo filed a 440 motion, a proceeding to have his conviction vacated. In support of his motion, DeFeo asserted that Dawn and an unknown assailant, who fled the house before he could get a good look at him, killed their parents and Dawn subsequently killed their siblings. He said the only person he killed was Dawn and that it was by accident as they struggled over the rifle. Again, he asserted he was married to Geraldine and that her brother was with him at the time of the murders. An affidavit from Richard Romondoe was submitted to the court, and it was asserted that he could not be located to testify in person. Evidence was submitted to the court by the Suffolk County District Attorney's Office suggesting that Richard Romondoe did not exist and that Geraldine Gates was living in upstate New York married to someone else at the time of the murders. Geraldine Gates did not testify at this hearing, because the authorities had already confronted her about the false claims; in 1992, they had secured a statement under oath in which she admitted that Romondoe was fictitious, and that she did not actually marry DeFeo until 1989 in anticipation of the filing of the 440 motion.[17][self-published source]

Judge Stark denied the motion, writing, "I find the testimony of the defendant overall to be false and fabricated. His testimony that during the fall of 1974 he was married and lived with his wife and child at Long Branch, New Jersey is incredible and not worthy of belief. He produced no corroborating evidence in this regard... another reason for my disbelief of defendant's testimony is demonstrated by consideration of several portions of the trial testimony... he signed a lengthy written statement describing in detail his activities... in this statement he said that he lived with his family at 112 Ocean Avenue in Amityville and that he worked for his father... that he usually went to and from work with his father; that he was ill and stayed home from work on November 12, 1974; that he was on probation for having stolen an outboard engine and had an appointment to see his probation officer in Amityville on that very afternoon... defendant's girlfriend, Mindy Weiss, testified that she began dating the defendant in June 1974, and was with him frequently that summer and fall." Stark further declared, "Defendant's testimony that he did not shoot and kill the members of his family is likewise incredible and not worthy of belief."[18]

On November 30, 2000, DeFeo met with Ric Osuna, the author of The Night the DeFeos Died, which was published in 2002. According to Osuna, they spoke for about six hours. However, in a letter to the radio show host Lou Gentile, DeFeo denied giving Ric Osuna information that could be used in his book, claiming that he immediately left the interview and did not speak to Osuna about anything substantive.[19]

According to Osuna, DeFeo claimed that he had committed the murders with his sister Dawn and two friends, Augie Degenero and Bobby Kelske, "out of desperation," because his parents had plotted to kill him. Allegedly, DeFeo claimed that, after a furious row with his father, he and his sister planned to kill their parents and that Dawn murdered the children to eliminate them as witnesses. He said that he was enraged on discovering his sister's actions, knocked her unconscious onto her bed, and shot her in the head. Police found traces of unburned gunpowder on Dawn's nightgown, which DeFeo proponents allege proves she discharged a firearm.[20] However, at trial, the ballistics expert, Alfred Della Penna, testified that unburned gunpowder is discharged through the muzzle of a weapon, indicating that she was in proximity to the muzzle of the weapon when it was discharged and not that she fired the weapon. He reiterated this on the 2006 A&E Amityville documentary First Person Killers: Ronald DeFeo.[21] This interview is extensively discussed in Will Savive's Mentally Ill In Amityville. Savive had an expert evaluate Della Penna's assessment and the expert confirmed that he was correct. Moreover, the medical examiner found nothing to indicate that Dawn had been in a struggle; the bullet wound was the only fresh mark on her body.

Skeptic Joe Nickell noted in 2003 that, given the frequency with which DeFeo had changed his story over the years, any further claims from him regarding the events that took place on the night of the murders should be approached with caution.[22]

Most of the claims made in Ric Osuna's book are sourced to DeFeo's ex-wife, Geraldine Gates. While in the 1986 interview with Newsday, she asserted she married DeFeo in 1974, in Osuna's book, she alleges they married in 1970. Their 1993 divorce case says that they met in 1985, married in 1989, and divorced in 1993.[23]

Death

[edit]Ronald DeFeo died aged 69 on March 12, 2021, at the Albany Medical Center. The official cause of death has not been released to the public.[24]

In popular culture

[edit]- Jay Anson's book The Amityville Horror was published on September 13, 1977. The book is based on the 28-day period during December 1975 and January 1976 when George and Kathy Lutz and their three children became the first family to live at 112 Ocean Avenue since the murders. The Lutz family left the house, claiming that they had been terrorized by paranormal phenomena while living there.[8] The book's 1979 film adaptation became the highest-grossing independent film of all time and held that record until 1990. It was followed by several sequels, as well as many other films which share no connection other than the reference to Amityville.[25]

- The 1982 film Amityville II: The Possession is based on the book Murder in Amityville by parapsychologist Hans Holzer. It is set at 112 Ocean Avenue, featuring the fictional Montelli family, who are based on the DeFeo family. The story introduces speculative and controversial themes, including an incestuous relationship between Sonny Montelli and his teenage sister Patricia, based loosely on a rumor of an incestuous relationship between DeFeo and his sister Dawn.[26]

- The 2019 film The Amityville Murders is another dramatization of the DeFeo murders and the circumstances surrounding them; unlike Amityville II: The Possession, the 2019 film retains the names of the real-life participants. Diane Franklin and Burt Young, who starred in Amityville II, appear in different roles in The Amityville Murders.[27]

- The film versions of the DeFeo murders contain several inaccuracies. The 2005 remake of The Amityville Horror contains a fictional child character called Jodie DeFeo. The claim that DeFeo was influenced to commit the murders by spirits from a Lenape burial ground on the site of 112 Ocean Avenue has been rejected by local historians and Native American leaders, who argue that there is insufficient evidence to support the claim that the burial ground ever existed.[28]

References

[edit]- ^ Barrett, Jackie (August 7, 2012). The Devil I Know: My Haunting Journey with Ronnie DeFeo and the True Story of the Amityville Murde rs. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-61066-4.

- ^ Barry-Dee, Christopher (2003). Talking with Serial Killers: The Most Evil People in the World Tell Their Own Stories. John Blake Publishing. ISBN 978-1-843-5-86173.

- ^ a b c Lynott, Douglas B. "The Real Life Amityville Horror". truTV Crime Library. Trutv.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008.

- ^ DJ - The Amityville Horror

- ^ "(Slideshow: Gunbox)". The Amityville Murders™. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008.

- ^ Lynott, Douglas B. "The Real Life Amityville Horror; Shots in the Night". truTV Crime Library. Trutv.com.

- ^ Bever, Lindsey (June 22, 2016). "The 'Amityville Horror' house is for sale: Five bedrooms, 3.5 bathrooms and one bloody history". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ a b Ramsland, Katherine: Inside the minds of mass-murderers: why they kill. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005, p. 80. ISBN 0-275-98475-3

- ^ Stark, Thomas M. (2021). Horrific Homicides: A Judge Looks Back at the Amityville Horror Murders and Other Infamous Long Island Crimes. Archway Publishing. ISBN 978-1-6657-1105-0.

- ^ "FACE OF 'HORROR' – AFTER 31 YEARS, THE AMITYVILLE KILLER SPEAKS". New York Post. April 20, 2006. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "'Amityville Horror' Killer Is Denied Parole Request". New York Times. September 24, 1999. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ "Amityville Killer Ronald DeFeo Jr. Dies In Prison - CBS New York". www.cbsnews.com. March 16, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ Gupte, Pranay (November 18, 1974). "Slain Family Drugged, Police on L:I..Report". The New York Times. Amityville, New York. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ Ramsland, Katherine. "Haunted Crime Scenes; Amityville Controversy". truTV Crime Library. Trutv.com. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ "The Amityville Murders". Amityvillemurders.com. Archived from the original on November 8, 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ Keeler, Bob. ""DeFeo's New Story," Newsday, March 19, 1986".

- ^ Osuna, Ric (2002). The Night The Defeos Died. Xlibris Corporation. pp. 334–35. ISBN 1401046452.

- ^ Stark, Thomas J.S.C: People v DeFeo Memorandum Denying Motion To Vacate Conviction, dated January 6, 1993, p. 3–4

- ^ "Ronnie DeFeo Jr". Amityvillehorrortruth.com. Archived from the original on July 1, 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ "Amityville - the Cultural Impact of Homicide". Castleofspirits.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ Stark, Thomas M. (October 28, 2021). Horrific Homicides: A Judge Looks Back at the Amityville Horror Murders and Other Infamous Long Island Crimes. Archway Publishing. ISBN 978-1-6657-1105-0.

- ^ Nickell, Joe (January 2003). "Amityville Horror Investigative Files (January 2003)". Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ New York Supreme Court DeFeo v. DeFeo.159 Misc. 2d 490; 605 N.Y.S.2d 202; 1993,

- ^ Valenti, John (March 15, 2021). "'Amityville Horror' killer Ronald DeFeo Jr. dies in state custody, officials say". Newsday. Archived from the original on March 15, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Miller, John M. "The Amityville Horror". Turner Classic Movies. In the Know. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ Amityville II: The Possession (1982) at IMDb

- ^ Harvey, Dennis (February 4, 2019). "Film Review: 'The Amityville Murders'". Variety. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ "The Amityville Murders". Amityvillemurders.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

External links

[edit]- 1951 births

- 2021 deaths

- 1974 murders in the United States

- 20th-century American criminals

- American mass murderers

- American murderers of children

- American people convicted of murder

- American people of Italian descent

- American people who died in prison custody

- Criminals from New York City

- People convicted of murder by New York (state)

- People from Amityville, New York

- Criminals from Brooklyn

- People from Long Island

- People with antisocial personality disorder

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by New York (state)

- Prisoners who died in New York (state) detention

- The Amityville Horror

- Parricides