Flesh for Frankenstein

| Flesh for Frankenstein | |

|---|---|

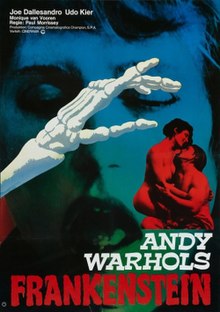

West German theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Paul Morrissey |

| Written by | Paul Morrissey |

| Based on | Frankenstein by Mary Shelley |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Luigi Kuveiller[1] |

| Edited by | Jed Johnson Franca Silvi[1] |

| Music by | Claudio Gizzi[2] |

Production company | Compagnia Cinematografica Champion[1] |

| Distributed by | Gold Film (Italy) Bryanston Distributing Company (USA) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 95 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $500,000[3] |

Flesh for Frankenstein is a 1973 horror film written and directed by Paul Morrissey. It stars Udo Kier, Joe Dallesandro, Monique van Vooren and Arno Juerging.

In West Germany and the United States, the film was released as Andy Warhol's Frankenstein and was presented in the Space-Vision 3D process in premiere engagements. It was rated X by the MPAA due to its explicit sexuality, nudity and violence. In the 1970s, a 3-D version played in London and Stockholm. A 3-D version also played in Australia in 1986, along with Blood for Dracula. The gruesomeness of the action was intensified in the original release by the use of 3D.[4]

Plot

[edit]Baron von Frankenstein neglects his duties towards his wife/sister Katrin, as he is obsessed with creating a perfect Serbian race to obey his commands, beginning by assembling a perfect male and female from parts of corpses. The doctor's sublimation of his sexual urges by his powerful urge for domination is shown when he utilizes the surgical wounds of his female creation to satisfy his lust. Frankenstein is dissatisfied with the inadequate reproductive urges of his current male creation and seeks a head donor with a greater libido; he also repeatedly exhibits an intense interest that the creature's "nasum" (nose) have a correctly Serbian shape.[4]

As it turns out, a suitably randy farmhand, Nicholas, leaving a local brothel along with his sexually repressed friend, brought there in an unsuccessful attempt to dissuade him from entering a monastery, are spotted and waylaid by the doctor and his henchman, Otto; mistakenly assuming that the prospective monk is also suitable for stud duty, they take his head for use on the male creature. Not knowing these behind-the-scenes details, Nicholas survives and is summoned by Katrin to the castle, where they form an agreement that he will gratify her unsatisfied carnal appetites.[4]

Under the control of Frankenstein, the male and female creatures are seated for dinner with the castle's residents, but the male creature shows no signs of recognition of his friend as he serves the doctor and his family. Nicholas realizes at this point that something is awry, but himself pretends not to recognize his friend's face until he can investigate further. After a falling-out with Katrin, who is merely concerned with her own needs, Nicholas goes snooping in the laboratory and is captured by the doctor. Frankenstein muses about using his new acquisition to replace the head of his creature, who is still showing no signs of libido. Nevertheless, Katrin is rewarded for betraying Nicholas by being granted use of the creature for erotic purposes, but is killed during a bout of overly vigorous copulation.

Meanwhile, Otto repeats the doctor's sexual exploits with the female creature, resulting in her graphic disembowelment. Frankenstein returns and, enraged, does away with Otto. When he attempts to have the male creature eliminate Nicholas, however, the remnants of his friend's personality rebel and the doctor is killed in gruesome fashion. The creature, believing he is better off dead, then disembowels himself. Frankenstein's children, Erik and Monica, then enter the laboratory and proceed to turn the wheel of the crane that is holding Nicholas in mid-air. To his surprise, the crane lifts him higher into the air as the children prepare scalpels.[4]

Cast

[edit]- Joe Dallesandro as Nicholas, The Stableboy

- Udo Kier as Baron Von Frankenstein

- Monique van Vooren as Baroness Katrin Frankenstein

- Arno Juerging as Otto, The Baron's Assistant

- Dalila Di Lazzaro as Female Monster

- Srdjan Zelenovic as Sacha / Male Monster, Nicholas' Friend

- Marco Liofredi as Erik Frankenstein, The Baron's Son

- Nicoletta Elmi as Monica Frankenstein, The Baron's Daughter

- Liù Bosisio as Olga, The Maid

- Cristina Gaioni as Nicholas' Girlfriend

Production

[edit]In 1973, Paul Morrissey and Joe Dallesandro came to Italy to shoot a film for producers Andrew Braunsberg and Carlo Ponti.[1] The original idea came from director Roman Polanski, who had met Morrissey when promoting his film What?, with Morrissey stating that Polanski felt he would be "a natural person to make a 3-D film about Frankenstein. I thought it was the most absurd option I could imagine." Morrissey convinced Ponti to not just make one film during this period, but two, which led to the production of both Flesh for Frankenstein and Blood for Dracula.[1] They were filmed at Cinecittà in Rome by a crew of Italian filmmakers. The staff included Enrico Job as the production designer, pianist Claudio Gizzi for the score and special effects artist Carlo Rambaldi for the special effects.[1] Warhol's contributions to the film were minimal, including visiting the set once and briefly visiting during the editing period.[1]

At first, Morrissey intended to rely on improvisation for the dialogue for his characters, but had to come up with a new method, as this would not work for some actors, such as Udo Kier.[1] This led to Morrissey preparing the dialogue day-by-day, dictating it to Pat Hackett at his studio.[1] Filming began on Flesh for Frankenstein on 20 March 1973.[1]

While some Italian prints credit second unit director Antonio Margheriti as director of the film under his pseudonym "Anthony M. Dawson", Udo Kier has stated that Margheriti had nothing to do with directing the film. Kier stated that he and the other cast members received direction only from Morrissey and noted that "Margheriti was on the set, he came to the studio from time to time, but he never directed the actors. Never!"[5] Margheriti was credited as the director to ensure the film would obtain Italian nationality for the producers due to Italian laws.[1][6] Tonino Guerra is credited as the screenwriter in the Italian prints as well, but his input is strictly limited to the Italian print of the film, as the only writer whose work on the film was ever evident was Morrissey himself.[1] Margheriti did shoot some special effects scenes, including the scene involving "breathing lungs" made from pigs' lungs.[1]

Release

[edit]Flesh for Frankenstein was shown in West Germany on November 30, 1973 as Andy Warhol's Frankenstein.[1] It was later shown on April 2, 1974 at Filmex, the Los Angeles International Film Exposition.[7] The film was submitted to Italian censors in January 1974 under the title Carne per Frankenstein, which was initially different from the American edit, containing some less explicit sex scenes and more violent death scenes.[1] That version was initially banned in Italy, but an edited version was resubmitted under the title Il mostro è in tavola, barone...Frankenstein, with changes to dialogue as well as the addition and removal of various scenes, giving it an 89-minute running time for distribution by Gold Film.[1]

The film earned $4.7 million in rentals in North America.[8] By 1974, the Los Angeles Times stated that the film had grossed $7 million.[9] In Italy, the film grossed a total of 345,023,314 Italian lire, an amount Italian film historian Roberto Curti described as "mediocre".[1]

Critical reception

[edit]Upon its release, Nora Sayre of The New York Times wrote, "In a muddy way, the movie attempts to instruct us about the universal insensitivity, living-deadness and the inability to be turned on by anything short of the grotesque. However, this 'Frankenstein' drags as much as it camps; despite a few amusing moments, it fails as a spoof, and the result is only a coy binge in degradation."[10]

Craig Butler of AllMovie called the film "a ramshackle affair, with performances that are ludicrously over-the-top and direction that is even more so, and a script that is filled with horrible dialogue. Not to mention, it's a truly gross experience. Of course, many will appreciate it just for these qualities, either to laugh at how truly outrageous it all is or to marvel at the manner in which director/writer Paul Morrissey is skewering the very countercultural sex revolutionaries that were among his biggest fans, creating what is at heart a very conservative critique of hippie culture."[11] Ian Jane of DVD Talk said of the film, "Flesh for Frankenstein is a morbid and grotesque comedy that won't be to everyone's taste but that does deliver some interesting humor and horror in that oddball way that Morrissey has."[12] Bruce G. Hallenbeck commented in his book, Comedy-Horror Films: A Chronological History, 1914-2008, that Flesh for Frankenstein is perverse and distasteful, but in a way which is deliberately parodical and even a political statement. He remarked, "The irony inherent in the screenplay by Morrissey and Tonino Guerra ... gives the film a winking detachment, so that you find yourself convulsed with laughter during some of the goriest scenes ever filmed."[13]

As of January 2018[update], the film held a 92% 'fresh' rating on movie review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes.[14] In 2012, Time Out polled authors, directors, actors and critics who had worked in the horror genre on their top horror films, with Flesh for Frankenstein placing at number 98 on the top 100.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Curti, Roberto (2017). Italian Gothic Horror Films 1970-1979. McFarland. pp. 80–84. ISBN 978-1476629605.

- ^ Alexander, Chris (6 October 2009). "Exclusive Interview with Composer Claudio Gizzi". Fangoria. Archived from the original on 14 October 2009.

- ^ Eichelbaum, Stanley (7 June 1974). "'Frankenstein' in 3-D--bigger than 'Trash'". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 28. Retrieved 26 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d Cullum, Brett (7 November 2005). "Flesh for Frankenstein". DVD Verdict. Archived from the original on 2 March 2006.

- ^ Del Valle, David (1995). Lucas, Tim (ed.). "Udo Kier: Andy Warhol's Horror Star [Interview]". Video Watchdog Special Edition. No. 2. Cincinnati, Ohio: Tim and Donna Lucas. pp. 40–56.

- ^ Alexander, Chris (4 November 2016). "Exclusive Interview: Udo Kier on Courier-X and Who Really Directed Dracula and Frankenstein". Coming Soon. Evolve Media.

- ^ Staff writer (17 March 1974). "Filmex". Calendar. Los Angeles Times. Vol. 93. Los Angeles, California. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "All-time Film Rental Champs", Variety, 7 January 1976 p. 48

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (9 November 1974). "'That'll Be the Day' Having Its Day". Los Angeles Times. p. a10 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sayre, Nora (16 May 1974). "Butchery Binge:Morrissey's 'Warhol's Frankenstein' Opens". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Butler, Craig. "Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) – Review – AllMovie". AllMovie. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Jane, Ian (19 November 2005). "Flesh for Frankenstein". DVD Talk. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ Hallenbeck, Bruce G. (2009). Comedy-Horror Films: A Chronological History, 1914-2008. McFarland & Company. pp. 101–103. ISBN 9780786453788.

- ^ "Flesh for Frankenstein – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ Clarke, Cath; Calhoun, Dave; Huddleston, Tom (13 April 2012). "The 100 best horror films: the list". Time Out. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013.

External links

[edit]- Flesh for Frankenstein at IMDb

- Flesh for Frankenstein at AllMovie

- Flesh for Frankenstein at the TCM Movie Database

- Flesh for Frankenstein at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Flesh for Frankenstein an essay by Maurice Yacowar at the Criterion Collection

- 1973 films

- Frankenstein films

- 1973 horror films

- 1970s erotic films

- 1970s 3D films

- French 3D films

- French science fiction horror films

- French splatter films

- Italian 3D films

- Italian science fiction horror films

- Films directed by Paul Morrissey

- Films set in castles

- Films set in Serbia

- Films about incest

- Films about sexuality

- Italian independent films

- Films about necrophilia

- Italian splatter films

- French independent films

- Films produced by Carlo Ponti

- English-language French films

- English-language Italian films

- Censored films

- Films shot at Cinecittà Studios

- 1970s exploitation films

- 1970s Italian films

- 1970s French films