Benjamin Kennicott

Benjamin Kennicott (4 April 1718 – 18 September 1783) was an English churchman and Hebrew scholar.

Life

[edit]Kennicott was born at Totnes, Devon where he attended Totnes Grammar School.[1] He succeeded his father as master of a charity school, but the generosity of some friends enabled him to go to Wadham College, Oxford, in 1744, and he distinguished himself in Hebrew and divinity. While an undergraduate he published two dissertations, On the Tree of Life in Paradise, with some Observations on the Fall of Man, and On the Oblations of Cain and Abel, which obtained him a B.A. before the statutory time.[2]

In 1747 Kennicott was elected a fellow of Exeter College, Oxford, and in 1750 he took his degree of M.A. In 1764 he was made a fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1767 keeper of the Radcliffe Library. He was also a canon of Christ Church, Oxford (1770), and rector of Culham (1753) in Oxfordshire, and was subsequently given the living of Menheniot, Cornwall, which he was unable to visit and resigned two years before his death.[2]

Works

[edit]Kennicott's major work is the Vetus Testamentum hebraicum cum variis lectionibus (1776–1780). Before this appeared he had written two dissertations entitled The State of the Printed Hebrew Text of the Old Testament considered, published respectively in 1753 and 1759, which were designed to combat contemporary ideas as to the "absolute integrity" of the received Hebrew text. The first contains "a comparison of I Chron. xi. with 2 Sam. v. and xxiii. and observations on seventy manuscripts, with an extract of mistakes and various readings"; the second defends the claims of the Samaritan Pentateuch, assails the correctness of the printed copies of the Aramaic translation, gives an account of Hebrew manuscripts of the Bible known to be extant, and catalogues one hundred manuscripts preserved in the British Museum and in the libraries of Oxford and Cambridge.[2]

In 1760 Kennicott issued proposals for collating all Hebrew manuscripts of date prior to the invention of printing. Subscriptions to the amount of nearly £10,000 were obtained, and many scholars agreed to participate, Paul Jakob Bruns of Helmstedt making himself specially useful as regarded manuscripts in Germany, Switzerland and Italy. Between 1760 and 1769 ten "annual accounts" of the progress of the work were given; in its course 615 Hebrew manuscripts and 52 printed editions of the Bible were either wholly or partially collated, and use was also made (but often very perfunctorily) of the quotations in the Talmud.[2]

The materials thus collected, when arranged and prepared for the press, extended to 30 volumes. The text finally followed in printing was that of Van der Hooght—unpointed however, the points having been disregarded in collation—and the various readings were printed at the foot of the page. The Samaritan Pentateuch stands alongside the Hebrew in parallel columns. The Dissertatio generalis, appended to the second volume, contains an account of the manuscripts and other authorities collated, and also a review of the Hebrew text, divided into periods, and beginning with the formation of the Hebrew canon after the return of the Jews from the exile.[2]

Kennicott's great work was in one sense a failure. It yielded no materials of value for the emendation of the received text, and by disregarding the vowel points overlooked the one thing in which some result (grammatical if not critical) might have been derived from collation of Massoretic manuscripts. But the negative result of the publication and of the Variae lectiones of De Rossi, published some years later, was important.[2] It showed that all Hebrew manuscripts of the Old Testament,[3] whatever their affinities and distinctions, were the result of an editorial process in antiquity that shields the original text from inquiry except indirectly through the study of versions and quotations. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls ended the transmissional monopoly of the Massoretic Text, but only in the Book of Isaiah and several much shorter passages, nonetheless comprising excerpts from almost every book of the Old Testament.[citation needed]

After Kennicott's death, his observations on Hebrew Bible passages were published as Remarks on Select Passages in the Old Testament (1787).

Kennicott Fellowship

[edit]Kennicott's work was perpetuated by his widow, who founded two university scholarships at Oxford for the study of Hebrew. The fund originally yielded an income of £200 per annum.[2] Currently, the Kennicott Fellowship is a postdoctoral Junior Research Fellowship in Ancient Hebrew, Hebrew Bible, and related topics.[4] The fellowship initially supported doctoral students but was later re-purposed to fund the present position. The current Kennicott Fellow is Hallel Baitner;[5] past fellows include S. R. Driver,[6] Norman Whybray,[7] Jocelyn Davey (Chaim Raphael),[8] Anselm Hagedorn,[9] Paul Joyce, [10] Jennie Grillo,[11] Timothy Lim,[12] Daniel Falk,[13] Katherine Southwood,[14] and John Screnock.[15] As of 2008, the value of the Kennicott Hebrew Fellowship was in the order of £19,263.[16]

Publications

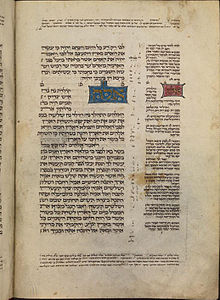

[edit]A full facsimile of the Bodleian Library's Kennicott Bible, MS. Kennicott 1, has been published.

Family

[edit]In 1771 Kennicott married Ann Chamberlayne, sister of Edward Chamberlayne the Treasury official, and sister-in-law of William Hayward Roberts. She survived him by many years, dying in 1831.[17] A friend of Hannah More, she knew Hugh Nicholas Pearson and was influenced by his evangelical faith. With Pearson as executor, she left property from the Chamberlayne estate in Norfolk to endow the two Hebrew scholarships at Oxford, mentioned above.[18]

References

[edit]- ^ Carlisle, Nicholas (1818). A Concise Description of the Endowed Grammar Schools in England and Wales. Vol. 1. London: Baldwin, Craddock and Joy. pp. 360–361. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Kennicott, Benjamin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 732–733.

- ^ The Kennicott Bible

- ^ "Kennicott Research Fellow - Classical Hebrew | data.ox.ac.uk". data.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "Hallel Baitner | Faculty of Oriental Studies". www.orinst.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Studies on the Language and Literature of the Bible: Selected Works of J. A. Emerton. Brill. p. 652.

- ^ "Obituaries" (PDF). Keble College: The Record 2009: 95.

- ^ Twentieth Century Crime and Mystery Writers. Macmillan. 1980. pp. 433.

- ^ Ancient Israel: The Old Testament in its Social Context. Fortress Press. 2006. pp. x.

- ^ "Paul Joyce".

- ^ The Romance between Greece and the East. Cambridge University Press. pp. viii.

- ^ Lim, Timothy (1997). Holy Scripture in the Qumran Commentaries and Pauline Letters. Oxford University Press. pp. vi.

- ^ "Daniel Falk – Jewish Studies Program". jewishstudies.la.psu.edu. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "Professor Katherine Southwood". St John's College. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "John Screnock | Faculty of Oriental Studies". www.orinst.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "Oxford University Gazette, 29 May 2008:Prizes, Grants, and Funding". Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- ^ Aston, Nigel. "Kennicott, Benjamin". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15407. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ John Stewart Reynolds (1953). The Evangelicals at Oxford, 1735-1871: A Record of an Unchronicled Movement with the Record Extended to 1905. Basil Blackwell. pp. 86 note 6.

External links

[edit]- Bodleian Library MS. Kennicott 1, the Kennicott Bible (full digitization)