Royal Canadian Mounted Police

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police Gendarmerie royale du Canada | |

|---|---|

![Badge of the RCMP[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/86/Coat_of_arms_of_the_Royal_Canadian_Mounted_Police.svg/140px-Coat_of_arms_of_the_Royal_Canadian_Mounted_Police.svg.png) | |

Patch (i.e. shoulder flash) of the RCMP | |

![Corps ensign of the RCMP[2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/25/Flag_of_the_Royal_Canadian_Mounted_Police.svg/140px-Flag_of_the_Royal_Canadian_Mounted_Police.svg.png) Corps ensign of the RCMP[2] | |

| Common name | The Mounties |

| Abbreviation |

|

| Motto | Maintiens le droit (French for 'uphold the right' / 'maintain the right' / 'defend the law')[1][3][4] |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | May 23, 1873 (NWMP formed)[5][6] February 1, 1920 (renamed to RCMP and absorption of Dominion Police)[7] |

| Preceding agencies |

|

| Employees | 30,092 (2019) |

| Volunteers | Approximately 1,600 auxiliary constables[8] |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Federal agency | Canada |

| Operations jurisdiction | Canada |

| Constituting instruments |

|

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Overseen by | Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

| Headquarters | M. J. Nadon Government of Canada Building 73 Leikin Drive Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0R2[9] |

| Sworn members | 22,445[10] (April 2019)

|

| Unsworn members | 5,759[10] (April 2019)

|

| Minister responsible | |

| Agency executive | |

| Parent agency | Public Safety Canada |

| Divisions | 15[10]

|

| Detachments | 712[11]

|

| Facilities | |

| Vehicles | 8,677

|

| Boats | 5 |

| Fixed-wings | 26[12] |

| Helicopters | 9[12] |

| Notables | |

| Significant incidents | |

| Awards | |

| Website | |

| www | |

| While a federal agency, the RCMP also serves as the local law enforcement agency for various provincial, municipal, and First Nations jurisdictions.[13] | |

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP; French: Gendarmerie royale du Canada; GRC) is the national police service of Canada. The RCMP is an agency of the Government of Canada; it also provides police services under contract to 11 provinces and territories, over 150 municipalities, and 600 Indigenous communities. The RCMP is commonly known as the Mounties in English (and colloquially in French as la police montée).

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police was established in 1920 with the amalgamation of the Royal North-West Mounted Police and the Dominion Police. Sworn members of the RCMP have jurisdiction as a peace officer in all provinces and territories of Canada.[14] Under its federal mandate, the RCMP is responsible for enforcing federal legislation; investigating inter-provincial and international crime; border integrity;[15] overseeing Canadian peacekeeping missions involving police;[16] managing the Canadian Firearms Program, which licenses and registers firearms and their owners;[17] and the Canadian Police College, which provides police training to Canadian and international police services.[18] Policing in Canada is considered to be a constitutional responsibility of provinces;[19] however, the RCMP provides local police services under contract in all provinces and territories except Ontario and Quebec.[20][21][note 1] Despite its name, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police are no longer an actual mounted police service, and horses are used only at ceremonial events and certain other occasions.

The Government of Canada considers the RCMP to be an unofficial national symbol,[22] and in 2013, 87 per cent of Canadians interviewed by Statistics Canada said that the RCMP was important to their national identity.[23] However, the service has faced criticism for its broad mandate,[24][25] and its public perception in Canada has gradually soured since the 1990s, worn down by workplace culture lawsuits, several high-profile scandals, staffing shortages, and the service's handling of incidents like the 2020 Nova Scotia attacks.[26][27] The treatment of First Nations people by the RCMP has also been criticized.

History

[edit]Early history (1920–1970)

[edit]

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police was formed in 1920 by the amalgamation of two separate federal police services: the Royal North-West Mounted Police (RNWMP), which had been responsible for colonial policing in the Canadian West,[28] but by 1920 was becoming "rapidly obsolete;"[29] and the Dominion Police, which was responsible for federal law enforcement, intelligence, and parliamentary security.[30] The new police service inherited the paramilitary, frontline policing-oriented culture that had governed the RNWMP, which had been modelled after the Royal Irish Constabulary,[31] but much of the RCMP's local policing role had been superseded by provincial and municipal police services.

In 1928, the federal government authorized the RCMP to enter into heavily subsidized contracts with provinces and municipalities, enabling the service to return to its roots in local policing. The federal government paid 60 per cent of the policing costs, while provinces and municipalities paid the remaining 40 per cent.[29] By 1950, eight of the ten Canadian provinces had disbanded their provincial police services in favour of subsidized RCMP policing.[32]

As part of its national security and intelligence functions, the RCMP infiltrated ethnic or political groups considered to be dangerous to Canada. These included the Communist Party of Canada (founded in 1921) and a variety of Indigenous, minority cultural, and nationalist groups.[33][need quotation to verify] The service was also deeply involved in immigration matters, and was responsible for deporting suspected radicals. The RCMP paid particular attention to nationalist and socialist Ukrainian groups[34] and the Chinese community, which was targeted because of disproportionate links to opium dens. Historians estimate that Canada deported two per cent of its Chinese community between 1923 and 1932, largely under the provisions of the Opium and Narcotics Drugs Act.[35] The first Mountie to go undercover was Frank Zaneth who under the code name Operative Number 1 infiltrated various "radical" groups along with the Mafia.[36]

In 1932, RCMP members killed Albert Johnson, the Mad Trapper of Rat River, after a shoot-out.[37] Johnson had been the subject of a dispute with local Indigenous trappers—he had reportedly destroyed their traps, harassed them verbally, and on one occasion, pointed a firearm at them—and, when confronted with a search warrant, opened fire on RCMP officers, wounding one.[37][38] Also in 1932, the Customs Preventive Service (CPS), a branch of the Department of National Revenue, was folded into the RCMP at the request of RCMP leadership.[39][40]

In 1935, the RCMP, acting as the provincial police service for Saskatchewan (but against the wishes of the Saskatchewan government)[23] and in collaboration with the Regina Police Service, attempted to arrest organizers of the On-to-Ottawa Trek in the Germantown neighbourhood's market square by kettling around 300 rally-goers, sparking the Regina Riot.[41] One city police officer and one protester were killed. The trek, which had been organized to call attention to conditions in relief camps, consequently failed to reach Ottawa, but nevertheless had political reverberations.[41] That same year, three RCMP members, acting under contract as provincial police officers, were killed in Saskatchewan and Alberta during an arrest and subsequent pursuit.[42]

During the interwar period, the RCMP employed special constables to assist with strikebreaking. For a brief period in the late 1930s, a volunteer militia group, the Legion of Frontiersmen, was affiliated with the RCMP.[43] Many members of the RCMP belonged to this organization, which was prepared to serve as an auxiliary police service.

In 1940, the RCMP schooner St. Roch facilitated the first effective patrol of Canada's Arctic territory. It was the first vessel to navigate the Northwest Passage from west to east, taking two years, the first to navigate the passage in one season (from Halifax to Vancouver in 1944), the first to sail either way through the passage in one season, and the first to circumnavigate North America (1950).[44]

In 1941, two African-Canadian men from Nova Scotia applied to join the RCMP. The commissioner at the time, Stuart Wood, allegedly allowed them to sit for entrance tests in the hopes that they could be definitively refused entry to the service as "their colour would raise the question of policy."[45] Both men ultimately passed the requisite tests, but neither was given an offer of employment.[45]

In the wake of the 1945 defection of Soviet cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko, who revealed that the Soviet Union was spying on Western nations, the RCMP separated its units responsible for domestic intelligence and counter-espionage from the Criminal Investigation Branch to the new Special Branch, formed in 1950.[46] The branch changed names twice: in 1962, to the Directorate of Security and Intelligence; and in 1970 to the Security Service.[46]

On April 1, 1949, Newfoundland and Labrador joined in Confederation with Canada, and the Newfoundland Ranger Force amalgamated with the RCMP.

In June 1953, the RCMP became a full member of the International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol).[47]

In 1969, the RCMP hired its first Black police officer, Hartley Gosline.[45]

Late 20th century

[edit]On July 4, 1973, during a visit to Regina, Saskatchewan, Queen Elizabeth II approved a new badge for the RCMP. The force subsequently presented the sovereign with a tapestry rendering of the new design.[48]

In 1978, the RCMP formed 31 part-time emergency response teams across the country to respond to serious incidents requiring a tactical police response.[49][50]

In 1986, in the wake of the 1985 Turkish embassy attack in Ottawa and the bombing of Air India Flight 182, the Canadian government directed the RCMP to form the Special Emergency Response Team (SERT), a full-time counter-terrorism unit.[51][52]

In the early 1990s, journalists at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's The Fifth Estate opened an investigation into rumours that a senior RCMP officer in the Criminal Intelligence Service (CISC) was on the payroll of a Montreal-based organized crime group, and in 1992, aired an episode identifying Inspector Claude Savoie, then the assistant director of the CISC, as the leak, citing evidence that connected him to Allan Ronald Ross, an Irish-Canadian drug lord, and Sidney Leithman, a prominent lawyer associated with Montreal's organized crime network.[53] Shortly after the episode aired, and minutes before being interviewed by detectives with the RCMP's professional standards unit, Savoie committed suicide in his Ottawa office.[54] One of Savoie's subordinates, Portuguese-Canadian constable Jorge Leite, was found guilty of corruption and breach of trust by a Portuguese court about his work with Savoie.[55][56]

In 1993, the SERT was transferred to the Canadian Forces, creating a new unit called Joint Task Force 2 (JTF2). The JTF2 inherited some equipment and the SERT's former training base near Ottawa.

In 1995 the Personal Protection Group (PPG) of the RCMP was created at the behest of Jean Chrétien after the break-in by André Dallaire at the Prime Minister's official Ottawa residence, 24 Sussex Drive.[57] The PPG is a 180-member group responsible for VIP security details, chiefly the prime minister and the governor general.[58]

RCMP Security Service (1950–1984)

[edit]The RCMP Security Service (RCMPSS) was a specialized political intelligence and counterintelligence branch with national security responsibilities following revelations of illegal covert operations relating to the Quebec separatist movement.[59] As a result, the RCMPSS was replaced by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) in 1984, and is statutorily independent of the RCMP.

In the late 1970s, revelations surfaced that the RCMP Security Service had in the course of their intelligence duties engaged in crimes such as burning a barn and stealing documents from the separatist Parti Québécois. This led to the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Certain Activities of the RCMP, better known as the "McDonald Commission", named for the presiding judge, Justice David Cargill McDonald. The commission recommended that the service's intelligence duties be removed in favour of the creation of a separate intelligence agency, the CSIS. The RCMP and the CSIS nonetheless continue to share responsibility for some law enforcement activities in the contemporary era, particularly in the anti-terrorism context.[60]

21st century

[edit]Due to 9/11, the RCMP Sky Marshals, which is charged with security on passenger aircraft, was inaugurated in 2002.[61]

Four RCMP officers were fatally shot during the Mayerthorpe tragedy in Alberta in March 2005. It was the single largest multiple killing of RCMP officers since the killing of three officers in Kamloops, British Columbia, by a mentally ill assailant in June 1962. Before that, the RCMP had not incurred such a loss since the North-West Rebellion.[62] One result was that on 21 October 2011 Commissioner William J. S. Elliott announced that RCMP officers would have the C8 rifle at their disposal, where in the past they had been limited to sidearms. One of the main conclusions from the fatality inquiry that led to this result was the fact that the officers who were involved in the events did not have the appropriate weapons to face someone with a semi-automatic rifle.[63]

In 2006, the United States Coast Guard's Ninth District and the RCMP began a program called "Shiprider", in which 12 Mounties from the RCMP detachment at Windsor and 16 U.S. Coast Guard boarding officers from stations in Michigan ride in each other's vessels. The intent was to allow for seamless enforcement of the international border.[64]

On December 6, 2006, RCMP Commissioner Giuliano Zaccardelli resigned after admitting that his earlier testimony about the Maher Arar case was inaccurate. The RCMP's actions were scrutinized by the Commission of Inquiry into the Actions of Canadian Officials in Relation to Maher Arar. In the aftermath of the Arar affair, the commission of inquiry recommended that the RCMP be subject to greater oversight from a review board with investigative and information-sharing capacities.[65] Following the commission of inquiry's recommendations, the Harper government tabled amendments to the RCMP Act to create the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission.[65]

In the wake of the 2007 Robert Dziekański taser incident at the Vancouver International Airport, two officers were found guilty of perjury to the Braidwood Inquiry and sentenced to jail for their actions. They appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada but were unsuccessful.

In July 2007, two RCMP officers were shot and succumbed to their injuries in the Spiritwood Incident near Mildred, Saskatchewan.[citation needed]

By the end of 2007, the RCMP was named Newsmaker of the Year by The Canadian Press.[66]

2010s

[edit]The RCMP mounted the Queen's Life Guard in May 2012 during celebrations of Queen Elizabeth II's Diamond Jubilee.[67]

On June 3, 2013, the RCMP's A Division was renamed the "National Division" and tasked with handling corruption cases "at home and abroad".[68]

In June 2014, three RCMP officers were murdered during the Moncton shooting.[69] A review from retired assistant commissioner Alphonse MacNeil in May 2015 issued 64 recommendations, while the RCMP was charged with violating the Canada Labour Code (CLC) for the slow roll-out of the C8 carbine, which had been recommended by the 2011 Elliott inquiry. The RCMP issued the first carbines in 2013, and with 12,000 members across the country had, as of May 2015, only purchased 2,200.[70] At the CLC trial the Crown argued that the then newly-retired head of the RCMP Bob Paulson had "played the odds" with officer safety and it proved fatal.[71] One result of the CLC trial was the conviction of the organization that had been led by Paulson for close to seven years.[72]

In October 2016, the RCMP issued an apology for harassment, discrimination, and sexual abuse of female officers and civilian members. Additionally, they set aside a $100 million fund to compensate these victims. Over 20,000 current and past female employees who were employed after 1974 are eligible.[73]

2020s

[edit]On March 10, 2020, Chief Allan Adam of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation was arrested by two RCMP officers in Fort McMurray, Alberta.[74][75] After several minutes of Chief Adam yelling and posturing at officers, the officers tackled him and punched him in the head whilst struggling with him on the ground. Chief Adam was later charged with resisting arrest and assaulting a peace officer, but the charges were subsequently dropped.[76] After watching the video of the arrest, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said, "[w]e have all now seen the shocking video of Chief Adam's arrest and we must get to the bottom of this".[77][74][78] Following the revelation of Chief Adam's arrest—as well as several other recent instances in which RCMP officers had assaulted or killed Indigenous people[79]—RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki stated, after initially demurring on the question, that systemic racism exists in the RCMP: "I do know that systemic racism is part of every institution, the RCMP included", she said.[80] One day earlier, Trudeau had also stated that "[s]ystemic racism is an issue right across the country, in all our institutions, including in all our police services, including in the RCMP."[81]

RCMP Constable Heidi Stevenson was killed while responding to the Wortman killing spree that left 23 dead in Nova Scotia in April 2020. The political furor that followed engulfed Commissioner Brenda Lucki and her minister, Public Safety Minister Bill Blair.[82] The RCMP was strongly criticized for its response to the attacks, the deadliest rampage in Canadian history,[83] as well as their lack of transparency in the criminal investigation. CBC News' television program The Fifth Estate and online newspaper Halifax Examiner analyzed the timeline of events, and both observed a myriad of failures and shortcomings in the RCMP response.[84][85][86] A criminologist criticized the RCMP's response as "a mess" and called for an overhaul in how the agency responds to active shooter situations, after they had failed to properly respond to other such incidents in the past.[87]

In the early 2020s, several governments, politicians, and scholars recommended terminating the RCMP's contract policing program.[88][89][90][91] Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino was mandated to conduct a review of RCMP contract policing when he took office in 2022.[92]

In June 2021, Privacy Commissioner of Canada Daniel Therrien found that the RCMP had broken Canadian privacy law through hundreds of illegal searches using Clearview AI.[93]

In February 2022, four men were arrested near Coutts, Alberta, for their roles in an alleged conspiracy to kill RCMP officers during the Canada convoy protest.[94]

On September 19, 2022, the RCMP led the procession through London, England, following the state funeral of Queen Elizabeth II due to the long-standing special relationship with the Queen.[95][96]

In 2023, the Mass Casualty Commission recommended that the RCMP replace its Depot-based training regime with a more intensive university-style program and that the federal public safety minister review the RCMP's involvement in contract policing.[97] Later that year, the force established a new direct-entry program for federal policing candidates.[98] Those recruited for the program will be required to complete a shorter, more focussed 14-week training curriculum in Ottawa before being posted to a federal policing position.[99] As of 2024, the implementation is suspended due to concerns raised by unions.[100]

In the early 2020s, the cities of Surrey, British Columbia, and Grande Prairie, Alberta, both established independent municipal police forces to replace the RCMP. In the wake of these decisions, and similar moves by the governments of Alberta and Saskatchewan to establish supplementary provincial police services to support (and, according to some critics, eventually replace) the RCMP, Commissioner Mike Duheme indicated that the RCMP was learning how to better manage transitions to local policing from contract policing.[101] Similar transitions have been proposed, debated, or approved in some Alberta First Nations, rural Manitoba, and rural New Brunswick.[102][103]

Role in colonization

[edit]As the federal police service, the RCMP has had an expansive and controversial role in colonization. One of the RCMP's two preceding agencies—the Royal Northwest Mounted Police (RNWMP)—had enjoyed a relatively positive relationship with the Indigenous peoples of Canada, buoyed by their role in restoring order to the Canadian west, which had been disrupted by immigrant settlement, and the stark contrast between Canadian policy and the ongoing American Indian Wars in the late 19th century.[28] After the signing of the Numbered Treaties between 1871 and 1899, however, the service generally failed to provide Indigenous communities with police services equal to those provided to non-Indigenous communities.[28]

American historian Andrew Graybill argued the RCMP historically resembled the Texas Rangers in many ways: each protected the established order by confining and removing Indigenous peoples; tightly controlling the mixed-blood peoples (the African Americans in Texas and the Métis in Canada); assisting the large-scale ranchers against the small-scale ranchers and farmers who fenced the land; and breaking the power of labour unions that tried to organize the workers of industrial corporations.[104]

From 1920 (1933, with respect to the Indian Act[105]) to 1996, RCMP officers served as truant officers for Indian residential schools, including through the transition of students from federal residential to provincial day schools after 1948,[106] assisting principals, staff, Indian agents, relatives, and members of the communities in bringing truant children to the schools,[107] sometimes by force,[108] as per the Indian Act[107] and as was common for truant non-Indigenous children through the same period.[109] Marcel-Eugène LeBeuf stated in his report for the RCMP that records and oral histories indicate the force "was responding, in its most traditional police role, to a request to protect children"[110] and that abuses within the school system were largely unreported to the RCMP at the time.[107]

During the federal government's imposition of municipal-style elected councils on First Nations, the RCMP raided the government buildings of particularly resistant traditional hereditary chiefs' councils and oversaw the subsequent council elections – the Six Nations of the Grand River Elected Council was originally referred to as the "Mounties Council" as a result of the RCMP's involvement in its installation.[111]

Role in land disputes

[edit]In 1995, the RCMP intervened in the Gustafsen Lake standoff between the armed Ts'peten Defenders, occupying what they claimed was unceded Indigenous land, and armed ranchers, who owned the land and had previously allowed Indigenous people to use part of it on the condition they not erect permanent structures. The RCMP's response included 400 tactical assault team members, five helicopters, two surveillance planes, and nine Bison armoured personnel carriers on loan from the Canadian Army[112] and sparked international controversy over the RCMP's use of unusually broad press exclusion zones.[113] One of the members of the Ts'peten Defenders was later granted political asylum in the United States after an Oregon judge found that the RCMP's reporting of the incident—marked by an RCMP member's off-hand comment to media that "smear campaigns are [the RCMP's] specialty"—amounted to a "disinformation campaign."[114][115]

Between January 2019 and March 2020, the RCMP spent $13 million policing and periodically enforcing injunctions against Indigenous protesters blocking the construction of a pipeline across what the protesters asserted was unceded Wet'suwet'en territory.[116] Wet'suwet'en hereditary chiefs Na'moks and Woos complained about the armed RCMP presence, as the police moved down the road, kilometre-by-kilometre, over days, dismantling fortified checkpoints and making arrests.[116] The RCMP's enforcement of a court injunction against the occupiers in 2020 sparked international controversy and protests and, as of 2022, sporadic occupations and protests—some violent—have continued at the site.[117]

Women in the RCMP

[edit]

In the 1920s, Saskatchewan provincial pathologist Frances Gertrude McGill began providing forensic assistance to the RCMP in their investigations.[118] She helped establish the first RCMP forensic laboratory in 1937,[119] and later was its director for several years. In addition to her forensic work, McGill also provided training to new RCMP and police recruits in forensic detection methods.[118] Upon her retirement in 1946, McGill was appointed honorary surgeon to the RCMP and continued to act as a dedicated consultant for the service up until her deatj in 1959.[120]

On May 23, 1974, RCMP Commissioner Maurice Nadon announced that the RCMP would accept applications from women as regular members of the service. Troop 17 was the first group of 32 women at Depot in Regina on September 16, 1974, for regular training.[121] This first all-female troop of 30 women graduated from Depot on March 3, 1975.[122]

After initially wearing different uniforms, female officers were finally issued the standard RCMP uniforms. Now all officers are identically attired, with two exceptions. The ceremonial dress uniform, or "walking-out order", for female members has a long, blue skirt and higher-heeled slip-on pumps plus a small black clutch purse (however, in 2012 the RCMP began to allow women to wear trousers and boots with all their formal uniforms).[123]) The second exception is the official maternity uniform for pregnant female officers assigned to administrative duties.

The following years saw the first women attain certain positions.

Organization

[edit]International

[edit]The RCMP International Operations Branch (IOB) assists the Liaison Officer (LO) Program to deter international crime relating to Canadian criminal laws. The IOB is a section of the International Policing, which is part of the RCMP Federal and International Operations Directorate. Thirty-seven liaison officers are placed in 23 other countries and are responsible for organizing Canadian investigations in other countries, developing and maintaining the exchange of criminal intelligence, especially national security with other countries, to assist in investigations that directly affect Canada, to coordinate and assist RCMP officers on foreign business and to represent the RCMP at international meetings.[127]

Liaison officers are in:

- Africa & Middle East:

- Asia-Pacific:

- Europe:

- The Americas:

The RCMP also provides law enforcement training overseas in Iraq and other Canadian peacekeeping missions. The RCMP has been involved in training and logistically supporting the Haitian National Police since 1994, a controversial matter in Canada considering allegations of widespread human rights violations on the part of the HNP. Some Canadian activist groups have called for an end to the RCMP training.[128]

National

[edit]The RCMP is organized under the authority of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act (RCMP Act), an act of the Parliament of Canada. Under sections 3 and 4 of the RCMP Act, the RCMP is a police service for Canada; namely, a federal police service.[129] However, section 20 of the RCMP Act provides that the RCMP may be used for law enforcement in provinces or municipalities if certain conditions are met.[130] As explained by Justice Ivan Rand of the Supreme Court of Canada, "what is set up is a police service for the whole of Canada to be used in the enforcement of the laws of the Dominion, but at the same time available for the enforcement of law generally in such provinces as may desire to employ its services."[131]

Under section 5 of the RCMP Act,[132] the agency is headed by the commissioner of the RCMP, who, under the direction of the minister of public safety and emergency preparedness, has the control and management of the service and all matters connected therewith. The RCMP is provided with a senior executive committee (SEC) which[133]

is the senior decision-making forum established by the Commissioner for the development and approval of strategic, service-wide policies, under and consistent with the Commissioner's authority under section 5 of the RCMP Act. The role of [the] SEC is to develop, promote, and communicate strategic priorities, strategic objectives, management strategies, and performance management for direction and accountability.

The commissioner is assisted by deputy commissioners in charge of Contract and Indigenous Policing, Federal Policing, and Specialized Policing Services. The commanding officers of K Division and E Division are also named deputy commissioners.[134]

Divisions

[edit]The RCMP divides the country into divisions for command purposes. In general, each division is coterminous with a province (for example, C Division in Quebec). The province of Ontario, however, is divided into two divisions: National Division (National Capital Region) and O Division (rest of the province). There is one additional division, Depot Division, which comprises the RCMP Academy in Regina and the Police Dog Service Training Centre[135] in Innisfail. The RCMP National Headquarters are in Ottawa, Ontario, established in 1920.[136]

| Division | Location | Year established | Headquarters |

|---|---|---|---|

| National (formerly A) | National Capital Region | 1874 | Ottawa |

| Depot | Regina | 1885 | Regina |

| B | Newfoundland and Labrador | 1874 | St. John's |

| C | Quebec | 1874 | Montreal |

| D | Manitoba | 1874 | Winnipeg |

| E | British Columbia | 1874 | Surrey |

| F | Saskatchewan | 1874 | Regina |

| G | Northwest Territories | 1885 | Yellowknife |

| H | Nova Scotia | 1885 | Halifax |

| J | New Brunswick | 1932 | Fredericton |

| K | Alberta | 1885 | Edmonton |

| L | Prince Edward Island | 1932 | Charlottetown |

| M | Yukon | 1904 | Whitehorse |

| O | Ontario | 1920 | Toronto |

| V | Nunavut | 1999 | Iqaluit |

Some historical divisions are no longer in use.

| Division | Location | Years established |

|---|---|---|

| HQ (now RCMP National Headquarters) | Ottawa | 1920–1987 |

| N (now Canadian Police College and Musical Ride headquarters) | Ottawa | 1905–1987 |

Detachments

[edit]

A detachment is a section of the RCMP that polices a local area. Detachments vary greatly in size. The largest single RCMP detachment is in the city of Surrey in British Columbia, with over a thousand employees. Surrey has contracted with the RCMP for policing services since 1951.[137] The second-largest RCMP detachment is in Burnaby, also in British Columbia.[138] Conversely, detachments in small, isolated rural communities have as few as three officers. The RCMP formerly had many single-officer detachments in these areas,[139][140] but in 2012 the RCMP announced that it was introducing a requirement that detachments should have at least three officers.[140]

As of 2022, several large Indigenous communities do not have RCMP detachments and are instead served by detachments in much smaller non-Indigenous communities.[141]

Personal Protection Group

[edit]

The Personal Protection Group (PPG) is a 180-member group responsible for security details for the monarch, other members of the royal family, and other VIPs.[58] It was created after the 1995 break-in at 24 Sussex Drive.[57] There are three units within the PPG: The Governor General's Protection Detail and the Prime Minister's Protection Detail provide bodyguards for the safety of the governor general of Canada and the prime minister of Canada, respectively, in Canada and abroad. These units are based in Ottawa, the former with operations at Rideau Hall (the monarch's and governor general's official residence in the capital) and the latter at 24 Sussex Drive (the prime minister's official residence) and Harrington Lake (the prime minister's retreat), near Chelsea, Quebec. The Very Important Persons Security Section provides security details to VIPs (including the chief justice of Canada, federal ministers other than the prime minister, and diplomats) and others under the direction of the minister of public safety.

Personnel

[edit]As of April 1, 2019[update], the RCMP employed 30,196 men and women, including police officers, civilian members, and public service employees.[10]

Actual personnel strength by ranks:

- Commissioners: 1

- Deputy commissioners: 6

- Assistant commissioners: 28

- Chief superintendents: 57

- Superintendents: 187

- Inspectors: 322

- Corps sergeants major: 1

- Sergeants major: 8

- Staff sergeants major: 9

- Staff sergeants: 838

- Sergeants: 2,018

- Corporals: 3,599

- Constables: 11,913

- Special constables: 122

- Civilian members: 7,695

- Public servants: 3,403

- Total: 30,196

Regular members

[edit]

The term regular member, or RM, originates from the RCMP Act and refers to the 18,988 regular RCMP officers who are trained and sworn as peace officers, and include all the ranks from constable to commissioner. They are the police officers of the RCMP and are responsible for investigating crime and have the authority to make arrests. RMs operate in over 750 detachments, including 200 municipalities and more than 600 Indigenous communities. RMs are normally assigned to general policing duties at an RCMP detachment for a minimum of three years. These duties allow them to experience a broad range of assignments and experiences, such as responding to emergency (9-1-1) calls, foot patrol, bicycle patrol, traffic enforcement, collecting evidence at crime scenes, testifying in court, apprehending criminals and plain clothes duties. Regular members also serve in over 150 different types of operational and administrative opportunities available within the RCMP, these include major crime investigations, emergency response, forensic identification, forensic collision reconstruction, international peacekeeping, bike or marine patrol, explosives disposal, and police dog services. Also included are administrative roles including human resources, corporate planning, policy analysis, and public affairs.

Auxiliary constables and other staff members

[edit]Besides the regular RCMP officers, several types of designations exist which give them assorted powers and responsibilities over policing issues.

Presently, there are:

- Community constables: Varies across Canada [citation needed]

- Reserve constables : Varies across Canada[142]

- Auxiliary constables: Varies across Canada[143]

- Special constables: 122[10]

- Civilian criminal investigators: 35 [144]

- Civilian members: 7,590[10]

- Public servants: 3,497[10]

Community constables (CC)

[edit]A designation introduced in 2014 as a replacement for the community safety officers and Indigenous community constables pilot programs.[145][146] Community constables are armed, paid members holding the rank of special constables, with peace officer power.[147] They are to provide a bridge between the local citizens and the RCMP using their local and cultural knowledge.[148] They are mostly focused on crime prevention, liaisons with the community, and providing resources in the event of a large-scale event.[149]

Reserve constables (R/Cst.)

[edit]A program reinstated in 2004 in British Columbia, it was later expanded to cover all of Canada to allow for retired, regular RCMP members and other provincially trained officers to provide extra manpower when shortages are identified.[150] R/Cst. are appointed under Section 11 of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Act as paid part-time, armed officers with the same powers as regular members.[151] However, they are not allowed to carry service-issued sidearms and use of force options unless they are called upon to duty.[150] They generally carry out community policing roles but may also be called upon if an emergency occurs.[150][152]

Auxiliary constables (A/Cst.)

[edit]Volunteers within their community, appointed under provincial police acts.[143] Auxiliary constables are not police officers and can not identify themselves as such. However, they are given peace officer powers when on duty with a regular member (RM). Their duties consist mainly of assisting RMs in routine events, for example, cordoning off crime scene areas, crowd control, participating in community policing, and assistance during situations where regular members might be overwhelmed with their duties (e.g., keeping watch of a backseat detainee while an RM interviews a victim). They are identified by the wording "RCMP Auxiliary" on cars, jackets, and shoulder flashes.

Special constables (S/Cst.)

[edit]Employees of the RCMP have varied duties depending on where they are deployed but are often given this designation because of the expertise they possess that needs to be applied in a certain area. For example, an Indigenous person might be appointed a special constable to assist regular members as they police an Indigenous community where English is not well understood, and where the special constable speaks the language well.

They still perform this role today in many isolated northern communities and the RCMP has 122 special constables who are active, and they are drawn almost entirely from the same Indigenous communities that they serve. From the early years of policing in northern Canada, and well into the 1950s, local Indigenous people were hired by the RCMP as special constables and were employed as guides to obtain and care for sled dog teams. Many of these former special constables still reside in the north to this day and are still involved in the regimental functions of the RCMP. Most pilots for RCMP aircraft, such as fixed-wing planes or helicopters, are special constables.

Civilian criminal investigators (CCI)

[edit]CCIs were implemented in 2021. They are civilian unarmed staff members, with limited peace officer status and are restricted from making physical arrests.[153] CCIs have backgrounds in computer science or financial markets and are involved in specialized investigations.[144] They participate in interviews, the preparation of court documents, and the searching of scenes.

Civilian members of the RCMP

[edit]While not delegated the powers of police officers, they are instead hired for their specialized scientific, technological, communications, and administrative skills. Since the RCMP is a multi-faceted law enforcement organization with responsibilities for federal, provincial, and municipal policing duties, it offers employment opportunities for civilian members as professional partners within Canada's national police service. Civilian members represent approximately 14 percent of the total RCMP employee population and are employed within RCMP establishments in most geographical areas of Canada. The following is a list of the most common categories of employment that may be available to interested and qualified individuals.

- Administrative

- Human resource management

- Police Records Information Management Environment (PRIME-BC)

- Policy development and analysis

- Staff development and training

- Translation

- Operations

- Telecommunications operator (dispatcher)[154]

- Scientific (forensic laboratory services)[155]

- Biology services

- Firearms and toolmark identification (covering Forensic firearm examination, ballistics, and related examinations)

- National Anti-counterfeiting Bureau

- Toxicology services

- Trace evidence

- Technical

- Communications

- Computer systems development

- Counterfeit analysis

- Document examination

- Electronics Technology

- Firearms technology

- Forensic identification services

- Information services and public affairs

- Information technology

- Instrument technology

- Telecommunications

Public service employees

[edit]Also referred to as public servants, PSes, or PSEs, they provide much of the administrative support for the RCMP in the form of detachment clerks and other administrative support at the headquarters level. They are not police officers, do not wear a uniform, have no police authority, and are not bound by the RCMP Act.

Municipal employees

[edit]Abbreviated as "ME" they are found in RCMP detachments where a contract exists with a municipality to provide front-line policing. MEs are not employees of the RCMP but are instead employed by the local municipality to work in the RCMP detachment. They conduct the same duties that a PSE would and are required to meet the same reliability and security clearance to do so. Many detachment buildings house a combination of municipally and provincially funded detachments, and therefore there are often PSEs and MEs found working together in them.

Ranks

[edit]The rank system of the RCMP is partly a result of their origin as a paramilitary service. Upon its founding, the RCMP adopted the rank insignias of the Canadian Army (which in turn came from the British Army). Like in the military, the RCMP also has a distinction between commissioned and non-commissioned officers.[156] The non-commissioned ranks are mostly based on military ranks (apart from constable). Non-commissioned officer ranks above staff sergeant resemble those that formerly existed in the Canadian Army, but have since been replaced by warrant officers.[157] The commissioned officer ranks, by contrast, use a set of non-military titles that are often used in Commonwealth police services. The number of higher ranks like chief superintendent and deputy commissioner have been added on and increased since the formation of the service, while the lower commissioned rank of sub-inspector has been dropped.

The numbers are current as of April 1, 2019:[158]

| Commissioned officers[159] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commissioner | Deputy commissioner | Assistant commissioner | Chief superintendent | Superintendent | Inspector |

| Commissaire | Sous-commissaire | Commissaire adjoint | Surintendant principal | Surintendant | Inspecteur |

| Commr. | D/Commr. | A/Commr. | C/Supt. | Supt. | Insp. |

| 1 | 6 | 33 | 55 | 186 | 331 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[160] These are the official abbreviations for the commissioned and non-commissioned officers in the RCMP.[161][162]

| Non-commissioned officers[159] | Constables | Depot | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

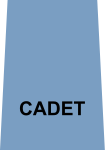

| Corps sergeant major | Sergeant major | Staff sergeant major | Staff sergeant | Sergeant | Corporal | Constable | Cadet |

| Sergent-major du corps | Sergent-major | Sergent-major d'état major | Sergent d'état-major | Sergent | Caporal | Gendarme | Cadet |

| C/S/M. | S/M. | S/S/M. | S/Sgt. | Sgt. | Cpl. | Cst. | Cdt. |

| 1 | 8 | 10 | 828 | 2,037 | 3,565 | 11,859 | Varies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

No Insignia |  |

The inspector ranks and higher ranks are commissioned ranks and are appointed by the Governor-in-Council. Depending on the badges and dresses which are worn on the shoulder as slip-ons, on shoulder boards, or directly on the epaulettes. The lower ranks are non-commissioned officers, and the insignia continues to be based on pre-1968 Canadian Army patterns. Since 1990, the non-commissioned officers' insignias & insignias have been embroidered on the epaulette slip-ons. Non-commissioned rank badges are worn on the right sleeve of the scarlet/blue tunic and blue jacket. Constables wear no rank insignia. There are also 122 special constables, as well as a varying number of reserve constables, auxiliary constables, and students who wear identifying insignia.

The star, or "pip", used in the insignia of commissioned officers represents the military Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath. The order's motto (tria juncta in uno, 'three joined in one', referring to the holy trinity) is inscribed in a band in the middle of it. The three crowns inset in the centre not only represent the Christian Trinity but also the three former kingdoms that became the United Kingdom. The RCMP formerly had subaltern (junior officer) ranks that were indicated by one "pip" for a sub-inspector (equivalent to an army second lieutenant) to three "pips" for an inspector (equivalent to an army captain).[163] A reorganization in 1960 changed the insignia to three "pips" for sub-inspectors[164] and a crown for inspectors,[165] making the latter a field officer rank. The rank of sub-inspector was abolished in 1990, leaving the RCMP with no subaltern ranks.

A royal crown is used in the regimental cap badge and the insignia of senior commissioned officers. In 1955 St. Edward's Crown replaced the Tudor Crown. Although Queen Elizabeth II adopted the redesign of the heraldic crown in 1953, it took some time to design, approve, and manufacture the new insignia. The crossed Mameluke sabre and baton is the insignia for general officers. In the RCMP it designates the commissioner (equivalent to an army general) and their subordinate deputy commissioners (equivalent to army lieutenant-generals). The assistant commissioners use the crown-over-three-pips insignia of an army brigadier. The brass shoulder title pin on the epaulettes was changed from "RCMP" to "GRC-RCMP" in 1968. (GRC stands for Gendarmerie royale du Canada, the RCMP's French-language title). This was due to a 1968 ruling stating that all statutes had to be published bilingually in both English and French. As a law enforcement agency, the RCMP had to use ranks and titles in both languages. This was later reinforced by the Official Languages Act.

Honorary positions and the role of the Royal Family.

[edit]Several members of the Canadian royal family hold honorary titles in the RCMP. These roles are comparable to the colonel-in-chief and honorary colonel positions in the Canadian Army, serving as promoters of the service's identity, traditions, and history, as well as making occasional visits to operational units. The commissioner-in-chief of the RCMP receives information and updates on important activities and serve as an advisor to the force's commanding officer; although, they do not play an operational role with the service.[166]

In addition to members of the Canadian Royal Family holding these positions, as federal law enforcement officers all members of the RCMP swear allegiance to the Monarch of Canada, presently King Charles III.[167]

Commissioner in chief

[edit]The commissioner-in-chief is the most senior honorary and ceremonial leadership position in the RCMP that is held by the Monarch of Canada, presently Charles III, King of Canada, who was bestowed the role prior to his coronation in 2023.[168]

The role was established as a separate role for the Canadian monarch from that of honorary commissioner in 2012, the first holder was Queen Elizabeth II who was bestowed the title in celebration of her diamond jubilee.[169] The role was created to show and maintain the close link between the Canadian monarch and the RCMP. The role has no day to day operational function but the commissioner-in-chief receives regular updates on the important activities of the RCMP, as well as promoting the Mounted Police both in Canada and abroad, and visiting RCMP events.[170] Upon appointment the commissioner-in-chief is presented with a Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer's sword, bearing the Canadian Coat of Arms and the Royal Cypher.[168]

Before the creation of commissioner in chief, the role of honorary commissioner was usually held by periodically by the Canadian monarchs and heir apparents, since 2023 the role of honorary commissioner is not currently in use.[170]

Honorary deputy commissioner

[edit]Honorary deputy commissioners are honorary positions held by senior members of the Canadian Royal Family, whose role is also to show the connection of the Royal Family and the RCMP.

The current honorary deputy commissioners are Anne, Princess Royal, and Edward, Duke of Edinburgh.[170]

Presently unused roles

[edit]Honorary commissioner was a role in the RCMP which had been held by Canadian monarchs and heir apparents, since April 2023 the role of honorary commissioner in not currently in use since Charles III's appointment as commissioner-in-chief.[168]

| Position | Holder | Duration | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title on taking post | Current title or title on vacating post | From | To | ||

| Honorary commissioner | Prince Edward, Prince of Wales | Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor | May 3, 1920 | 1937[166] | To coincide with the change of name from Royal Northwest Mounted Police to Royal Canadian Mounted Police[171] |

| Honorary commissioner | Queen Elizabeth II | Same | July 7, 1953 | May 10, 2012[175] | |

| Commissioner-in-chief | May 10, 2012 | September 8, 2022 | In celebration of her Diamond Jubilee[173][176] | ||

| Honorary deputy commissioner | Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex | Prince Edward, Duke of Edinburgh | October 12, 2007 | Present[166] | Accepted title at an RCMP regimental dinner.[166] |

| Honorary commissioner | Prince Charles, Prince of Wales | King Charles III | May 10, 2012 | April 28, 2023 | Accepted title at Depot Division when the Queen became commissioner-in-chief[166][173] |

| Commissioner-in-chief | King Charles III | Same | April 28, 2023 | Present | Appointment conferred in a ceremony at Windsor Castle[177] |

| Honorary deputy commissioner | Princess Anne, Princess Royal | Same | November 10, 2014 | Present[178] | Accepted title at the Musical Ride Centre[166] |

Equipment and vehicles

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Fleet data is from 2010, over 13 years ago.. (August 2023) |

Land fleet

[edit]

The RCMP Land Transport Fleet inventory includes:[179]

- Cars: 5,330

- Unmarked vehicles: 2,811

- Light trucks: 2,090

- Heavy trucks: 123

- SUVs: 616

- Motorcycles: 34

- Small snowmobiles: 481

- All-terrain vehicles: 181

- Tractors: 27

- Buses: 3

- Armoured Personnel Carriers: 2

- Total: 11,699

Marine craft

[edit]

The RCMP policies Canadian Internal Waters, including the territorial sea and contiguous zone as well as the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence Seaway; such operations are provided by the RCMP's Federal Services Directorate and include enforcing Canada's environment, fisheries, customs, and immigration laws. In provinces and municipalities where the RCMP performs contract policing, the service polices freshwater lakes and rivers.

To meet these challenges, the RCMP operates the Marine Division, with five Robert Allan Ltd.–designed high-speed catamaran patrol vessels; Inkster and the Commissioner-class Nadon, Higgitt, Lindsay and Simmonds, based on all three coasts and manned by officers specially trained in maritime enforcement. Inkster is based in Prince Rupert, BC, Simmonds is stationed on Newfoundland's south coast, and the rest are on the Pacific Coast.[180] Simmonds' livery is unique, in that it sports the RCMP badge, but is otherwise painted with Canadian Coast Guard colours and the marking Coast Guard Police. The other four vessels are painted with blue and white RCMP colours.

The RCMP operates 377 smaller boats, defined as vessels less than 9.2 m (30 ft) long, at locations across Canada. This category ranges from canoes and car toppers to rigid-hulled inflatables and stable, commercially built, inboard-outboard vessels. Individual detachments often have smaller high-speed rigid-hulled inflatable boats and other purpose-built vessels for inland waters, some of which can be hauled by road to the nearest launching point.[180]

| Ship name | Type | Class | Base | Specifications | Propulsion | Top speed | Builder | Year commissioned | Crew |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inkster | Patrol vessel | n/a | Prince Rupert, BC | 19.75 m (64.8 ft) fast patrol aluminium catamaran |

25 kn (46 km/h; 29 mph)+ | Allied Shipbuilders Limited of North Vancouver, BC | 1996 | 4 | |

| Nadon | Patrol vessel | Commissioner Class PV (Raven Class) | Nanaimo, BC | 17.7 m (58 ft) fast patrol catamaran |

2 × 820 hp (610 kW) D2840 LE401 V-10 MAN Diesel engines | 36 kn (67 km/h; 41 mph) | Robert Allan Ltd. | 1991 | 4 |

| Higgitt | Patrol vessel | Commissioner Class PV | Campbell River, BC | 17.7 m (58 ft) fast patrol catamaran |

2 × 820 hp (610 kW) D2840 LE401 V-10 MAN Diesel engines | 36 kn (67 km/h; 41 mph) | Robert Allan Ltd. | 1992 | 4 |

| Lindsay | Patrol vessel | Commissioner Class PV | Patricia Bay, Victoria, BC | 17.7 m (58 ft) fast patrol catamaran |

2 × 820 hp (610 kW) D2840 LE401 V-10 MAN Diesel engines | 36 kn (67 km/h; 41 mph) | Robert Allan Ltd. | 1993 | 4 |

| Simmonds | Patrol vessel | Commissioner Class PV | South coast Newfoundland | 17.7 m (58 ft) fast patrol catamaran |

2 × 820 hp (610 kW) D2840 LE401 V-10 MAN Diesel engines | 36 kn (67 km/h; 41 mph) | Robert Allan Ltd. | 1995 | 4 |

Aircraft fleet

[edit]

As of February 2023, the RCMP had 35 police aircraft (9 helicopters and 26 fixed-wing aircraft) registered with Transport Canada and operate as ICAO airline designator SST, and telephony STETSON.[181][12] All aircraft are operated and maintained by the Air Services Branch.

| Aircraft | Number[12] | Variants | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerospatiale AS350 Écureuil | 6 | AS 350B3 | Helicopter, AStar 350 or "Squirrel" |

| Airbus H145 | 1 | H145 | Helicopter, light twin-engine, four-axis autopilot. Serving the Lower Mainland of BC ("E" Division) |

| Cessna 206 | 5 | U206G, T206H | Fixed wing, Stationair (station wagon of the air), general aviation aircraft |

| Cessna 208 Caravan | 3 | 208, 208B | Fixed wing, caravan, short-haul regional airliner and utility aircraft |

| de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter | 1 | 300 Series | Fixed wing, 20-passenger STOL feederliner and utility aircraft, twin-engine. |

| Eurocopter EC120 Colibri | 2 | EC 120B | Light helicopter, "Hummingbird" |

| Pilatus PC-12 | 15 | PC-12/45, PC-12/47, PC-12/47E | Fixed wing, turboprop passenger and cargo aircraft |

| Quest Kodiak | 1 | 100 | Fixed-wing, un-pressurized, turboprop-powered fixed-tricycle-gear, STOL |

Weapons and intervention options

[edit]

- Smith & Wesson Model 5946 (1992–present) – Standard full-sized service sidearm. It is stainless-steel, double-action only, with a 4 in (100 mm) barrel and a double-column 15-round magazine.

- Emergency response team (ERT) and dog handler members were issued modified Model 5946s with magazine safeties removed until they were replaced with the SIG Sauer P226R.

- Smith & Wesson Model 3953 (1996–present) – Special issue compact sidearm for plainclothes members and commissioned officers. It can also be requested as a service pistol by members with small hands who cannot positively grip the larger Model 5946. It is similar to the Model 5946 except it has a shorter 3.5 in (89 mm) barrel, a shortened grip, and a single-column eight-round magazine.

- SIG Sauer 226R (9×19mm) – Standard issue sidearm for ERT and dog-handler members. It replaced the modified Model 5946 that had been previously issued.

- Glock Model 19 – Special issue sidearm for Canadian Air Carrier Protective Program (CACPP) members.

- Heckler & Koch MP5 – Adopted by the ERT

- Remington Model 700 (.308 Winchester) bolt-action rifle

- Remington 870 12-gauge shotgun

- Colt Canada C7 rifle (5.56mm NATO)

- Colt Canada C8 carbine (5.56mm NATO) – Adopted by ERT

- Colt Canada C8 IUR (integrated upper receiver) 5.56mm NATO. The semi-automatic C8 IUR was adopted for general use in October 2011,[182] but the first batch were not procured until 2013.[183] The first RCMP Cadets began qualifying on the C8 IUR and receiving Active Shooter training in 2015.[184]

- Taser International M26, X26, and X26P. Following the Robert Dziekański incident, all older M26 models and 60 faulty X26 models in stock were removed and destroyed in 2010 due to being outside of specifications.[185]

- Oleoresin capsicum spray

- ASP and Monadnock expandable defensive batons

Past weapons and intervention options

[edit]- Rifles

- Canadian Arsenals Limited (CAL) C1A1 – issued in 7.62mm NATO. Canadian variant of the FN FAL and L1A1 produced under licence by Canadian Arsenals Limited (CAL) (Long Branch). The RCMP's rifles were sourced from the testing batch of FALs received from Fabrique Nationale and had been rebuilt by CAL to meet C1A1 standards. Used from 1961 to 1969.

- Winchester Model 70 Issued in .308 Winchester. Used from 1960–1973. This rifle was replaced by the Remington 700.

- Lee–Enfield No. 4 Mk 1 – issued in .303 British. World War II surplus rifles were used from 1947 to 1966. Replaced by CAL C1A1 and Winchester 70.

- Short Magazine Lee Enfield (SMLE) No. 1 Mk III – issued in .303 British. World War I surplus rifles used from 1919–1947.[186]

- Lee-Enfield carbine (LEC) – issued in .303 British. Procured as military surplus from militia stores to replace the unsatisfactory Ross Rifle. Used from 1914 to 1920. This was the last general-issue rifle used by the NWMP. The RCMP that replaced it only issued rifles according to need.

- Ross rifle – issued in .303 British. The Ross Mk I was issued from 1905 to 1907 and the improved Ross Mk II was in testing from 1909 to 1912.[186] The Mk I design was accepted by the Canadian Militia in 1903. The NWMP looked at acquiring the Ross to replace the Winchester and Lee-Metford and ordered 1000. Production problems led to delays until 1904; the most glaring being that the finished product did not match their original specifications.[186] The NWMP demanded their contract carbines use a different set of iron sights (which later became standard on the Mk II) which delayed production for a further year.[186] The carbines received in 1905 were plagued with quality control problems that made them more fragile than the weapons they were to replace. After a constable suffered an eye injury in 1907 the Ross carbines were withdrawn.[186] When the improved Ross Mk II rifles arrived in 1909 the wary NWMP decided to test-fire all of them fully before issuing them. A fire at the depot in Regina in 1911 destroyed almost all of the new rifles.[186] The NWMP then gave up on the Ross.

- Magazine Lee-Enfield (MLE) Mk.I rifle – issued in .303 British; it was the first smokeless powder weapon in NWMP service. Loaned to the NWMP from the Victoria and Winnipeg militias to replace a stolen cache of M1876 Winchesters. The NWMP "forgot" to give them back later. Used from 1902 to 1920.

- Lee-Metford carbine – issued in .303 British. The Metford rifling gave tighter groups when fired than the later Enfield, but the rifling wore out faster. Only 200 were procured. Used from 1895 to 1914. Replaced by the Lee-Enfield carbine.

- Winchester Model 1876 saddle carbine – issued in .45-75 Winchester. Popular for its handiness and rate of fire, but it was too fragile for the rough handling and use it received in the field. Used from 1878 until 1914.[187] and replaced by the Lee-Enfield Carbine.

- Snider–Enfield Mark III cavalry carbine – issued in .577 Snider. Single-shot breach-loading conversion of an Enfield caplock muzzle-loader. Used from 1873 to 1878 and replaced by the Winchester Model 1876 lever-action rifle.

- Service pistols

- Smith & Wesson military and police revolver – issued with 5 in (130 mm) barrel, in .38 Special. It served more than forty years from 1954 to 1996. Plainclothes members carried a variant with a 4 in (100 mm) barrel.

- In 1981, the standard loading was changed from a 158 gr (0.36 oz; 10.2 g) .38 Special full metal jacket (FMJ) ball round to a 158 gr (0.36 oz; 10.2 g) .38 Special +P semi-wadCutter hollow-point (SWCHP), a violation of the Hague Convention of 1899 if used in a military context.[188]

- Colt New Service revolver – issued with 5.5 in (140 mm) barrel; 700 ordered in .455 Webley in 1904, with .45 Long Colt versions being delivered from 1919; in all, over 3,200 were issued.[188][186] 455 Webley was the British military service round, and .45 Long Colt was the standard Canadian service round until both were replaced by the NATO-standard 9×19mm Parabellum post World War II. Used from 1904 to 1954.

- Enfield Mark II revolver – issued in .476 Enfield, about 1080 Mark IIs obtained from Britain's Ministry of Defence, after it was learned the Beaumont–Adams had been discontinued.[189][186] The remaining .450 Adams ammunition, which was compatible with the .476 Enfield round, was issued until stocks were depleted. Used from 1882 to 1911.

- Beaumont–Adams revolver – first issue weapon, in .450 Adams. 330 Mark Icas was purchased from Britain's Ministry of Defence in 1873 and issued after delivery in 1874. Rough handling of the crates in transit, poor packing by the contractor who shipped the guns, and previous service wear made them unsuitable for service.[186] The constables sometimes had to manually turn the cylinders due to cracked feed hands or keep both hands on the grips for the springs to work due to loose screws.[190] Later, these were to be replaced by 330 Enfield Mark IIs,[191] but many were stolen en route.[190] Used from 1874 to 1888.

- Pistols

Due to procurement problems with the Beaumont–Adams revolvers, constables sometimes carried their sidearms chambered in a standard service calibre.

- Tranter revolver – chambered in .450 Adams, the standard service round. It was similar to the Beaumont-Adams revolver it was substituted for.

- Smith & Wesson Model 3 revolver – chambered in .44 Russian, a very powerful cartridge in its day. Thirty were purchased in 1874 by the NWMP to field-test the .44 Russian round for service. Its non-standard chambering and the difficulty of getting ammunition for it led to its being withdrawn.

- Webley & Scott Bull Dog revolver[192] – chambered in .450 Adams. Its small size made it a handy backup pistol. Most were originally procured to arm NWMP constables assigned to protecting mail cars on trains. The constables would sometimes "absent-mindedly forget" to hand the pistols back afterwards.

- Sidearms

- 1821 pattern light cavalry sabre – Originally part of a trove of old swords given by the Canadian Militia to the NWMP as weapons. They were returned to stores in 1880. Later issued to commissioned officers in 1882 as ceremonial sidearms and a sign of rank. This was later replaced by the M1896 light cavalry sabre.

- 1853 pattern cavalry sabre – Originally part of a trove of old swords given by the Canadian Militia to the NWMP as weapons. They were returned to stores in 1880. Later issued in 1882 to non-commissioned officers as ceremonial sidearms and a sign of rank. This was later replaced by the 1821 pattern sabre.

- 1896 pattern light cavalry sabre – Replaced the 1821 pattern sabre as the NWMP officer's ceremonial sword.

- 1908 pattern cavalry sabre – Carried by the Mounted Police detachment sent to Siberia in 1918 during the Russian Civil War.

- Straightstick baton manufactured in wood and plastic

- Sap gloves – Prohibited by RCMP policy. Presently not used.

Ceremonial weapons and symbols of office

[edit]- 1912 pattern cavalry officer's sword carried by officers. The blade is acid etched on both sides with the monarch's crown, Canadian coat of Arms, royal cypher, and RCMP badge.

- 1908 pattern cavalry sword carried by NCOs on the Musical Ride

- Bamboo-shafted lance carried by members on horseback on the Musical Ride. The lance is used as a decorative item and flourishes during trick and formation riding. The pennant is red over white, the national colours of the Canadian flag. It represents the Pattern 1868 cavalry lance carried by the NWMP in the 1870s.

- Drill cane

- Swagger stick

- Commissioner's tipstaff

In 1973, Wilkinson Sword produced several commemorative swords to celebrate the RCMP centennial. None of these swords was ever used ceremonially and were strictly collectables. Wilkinson Sword also made a commemorative centennial tomahawk and miniature "letter opener" models of their centennial swords. During the same year, Winchester Repeating Arms Company produced an RCMP commemorative centennial version of their Model 94 rifle in .30-30 Winchester, with a 22 in (560 mm) round barrel. The receiver, buttplate, and forend cap (on the musket-style forend) were plated in gold. Commemorative medallions were embedded in the right-hand side of the stock, with an "MP" engraving. There was engraving on the barrel and receiver indicating the rifle was a centennial commemorative edition. Sights were open notch rear, with a flip-up rear ladder, graduated to 2,000 yd (1,800 m). Two versions were produced, 9500 with serial numbers beginning "RCMP" for commercial sale, and 5000 with the prefix "MP" sold only to serving RCMP members. In addition, ten presentation models were produced, serially RCMP1P to RCMP10P.[193]

Uniform

[edit]Operational uniform

[edit]

RCMP officers on frontline police duties wear grey shirts with RCMP shoulder flashes, navy blue pants with gold trouser piping, bulletproof vests, and a peaked cap with a solid gold band. High-ranking officers wear white shirts. A tie can be worn with a long-sleeved shirt for occasions such as testifying in court. In colder weather, members may wear heavier boots, winter coats, wool toques, or uniquely, muskrat fur caps.[194]

In 1990, Baltej Singh Dhillon became the RCMP's first Sikh officer to be allowed to wear a turban instead of the traditional campaign hat.[195] During the COVID-19 pandemic, Sikh, Muslim, and other bearded officers were initially assigned to administrative duties before being permitted to attend calls for service with low viral transmission risks after officer outcry.[196] The beards required as part of the Sikh practice of kesh and worn by some Muslim men prevented respirator masks from properly sealing around the mouth and nose, reducing their effectiveness.[196][197] As of 2019, all RCMP officers, regardless of religious belief, are allowed to wear full beards or braided hair below their collar.[198] Officers may also wear a ballcap in place of the traditional peaked cap.[198]

Dress uniform

[edit]

RCMP officers are equipped with a dress uniform, popularly known as the "blue serge", for performing certain formal duties, such as media relations or parliament testimony. It consists of a navy blue dress jacket with epaulets and brass buttons, a white shirt, a navy blue tie, navy blue pants with gold trouser piping, and a peaked cap with a solid gold band.[199] Shoulder flashes are not worn.

Ceremonial uniform

[edit]

For most formal and ceremonial duties, RCMP wears the internationally-famous Red Serge.[200] It has a high collared scarlet tunic, which was developed by the North-West Mounted Police and colored red to distinguish it from blue American military uniforms, midnight blue breeches with yellow trouser piping, an oxblood Sam Browne belt with white sidearm lanyard and matching oxblood riding boots, brown felt campaign hat with a "Montana crease" (pinched symmetrically at the four corners), and oxblood gloves.[199] Since 1990, identical ceremonial uniforms have been worn by both men and women.[201]

Decorations

[edit]Members receive a clasp and service badge star for every five years of service.[202] The King of Canada also awards the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Long Service Medal to members who have completed 20 years of service. A clasp is awarded for each successive 5 years to 40 years. Members also receive a service badge star for each five years of service, which is worn on the left sleeve. There are specialist insignia for positions such as first aid instructor and dog handler, a fingerprint insignia for forensic identification specialists, and pilot's wings worn by aviators. Sharpshooter badges for proficiency in pistol or rifle shooting are each awarded in two grades.[202] Sharpshooter badges and service badge stars are sewn onto the left sleeve of the red serge.

Tartan

[edit]

The RCMP has since 1998 had its own distinctive tartan. The creation of the tartan was the result of a committee created in the early 1990s to create a tartan by its 125th anniversary. Upon approval from Commissioner Phillip Murray, the tartan was registered with the Scottish Tartans Society and presented to the agency by Anne, Princess Royal during her royal visit to Canada in 1998. The tartan appeared for the first time by an RCMP pipe band at the Royal Nova Scotia International Tattoo in July and August 1998.[203]

Military status

[edit]

| |

|---|---|

1973–2023 guidon of the RCMP | |

| Active | 1873–present |

| Country | Canada |

| Type | Dragoons |

| Battle honours | see Battle honours |

| Commanders | |

| Commissioner-in-chief | King Charles III[177] |

| Commissioner | Michael Duheme |

| Honorary deputy commissioners | The Duke of Edinburgh[204] The Princess Royal[205] |

| Insignia | |

| Tartan | RCMP |

| Abbreviation | RCMP/GRC |

Although the RCMP is a civilian police service, in 1921, following the service of many of its members during the First World War, King George V awarded the service the status of a regiment of dragoons, entitling it to display the battle honours it had been awarded.

Service in wartime

[edit]During the Second Boer War, members of the North-West Mounted Police were given leaves of absence to join the 2nd Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles (CMR) and Strathcona's Horse. The service raised the Canadian Mounted Rifles, mostly from NWMP members, for service in South Africa. For the CMR's distinguished service there, King Edward VII honoured the NWMP by changing the name to the "Royal Northwest Mounted Police" (RNWMP) on June 24, 1904.

During the First World War, the Royal Northwest Mounted Police (RNWMP) conducted border patrols, surveillance of enemy aliens, and enforcement of national security regulations within Canada. However, RNWMP officers also served overseas. On August 6, 1914, a squadron of volunteers from the RNWMP was formed to serve with the Canadian Light Horse in France. In 1918, two more squadrons were raised, A Squadron for service in France and Flanders and B Squadron for service in the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force.

In September 1939, at the outset of the Second World War, the Canadian Army had no military police. Five days after war was declared the Royal Canadian Mounted Police received permission to form a provost company of service volunteers. It was designated "No. 1 Provost Company (RCMP)", and became the Canadian Provost Corps. Six months after war was declared its members were overseas in Europe and served throughout the Second World War as military police.

RCMP members were embedded with several military units in Afghanistan during the War in Afghanistan from 2001–14. The RCMP was a member agency of the Afghan Threat Finance Cell, a multi-agency intelligence organization formed in 2008.[206]

Honours

[edit]The Royal Canadian Mounted Police were accorded the status of a regiment of dragoons in 1921. As a cavalry regiment, the RCMP was entitled to wear battle honours for its war service as well as carry a guidon, with its first guidon presented in 1935.[207][208] The second guidon was presented in 1973, and the third in 2023.[209]

Battle honours

- North West Canada 1885

- South Africa 1900–1902

- France & Flanders 1918

- Siberia 1918–19

- Second World War 1939–1945 Seconde Guerre mondiale

- Afghanistan 2003–14[210]

The RCMP also carries the honorary distinctions for the Canadian Provost Corps (Military Police), presented September 21, 1957, at a Parliament Hill ceremony for contributions to the corps during the Second World War. The honorary distinction was recognized on the guidon presented in 2023 with its inclusion among other RCMP battle honors.[209]

Public perception

[edit]The Mounties have been immortalized as symbols of Canadian culture in numerous Hollywood Northwestern movies and television series, which often feature the image of the Mountie as square-jawed, stoic, and polite, yet with a steely determination and physical toughness that sometimes appears superhuman. The RCMP's motto is the French phrase, Maintiens le droit, variously translated into English as "Defending the Law", "Maintain the right", and "Uphold the right".[1][3][4] The Hollywood saying that they 'always get their man' derives ultimately from the words "They fetch their man every time" occurring in a report made at Fort Benton regarding an incident at Fort Macleod in 1877, when two Mounties, notwithstanding the loss of their horses, managed to capture three whisky smugglers.[211]

In recent decades, Canadian public perception of the RCMP has become less favourable. In 2022 Angus Reid survey found that 41 per cent of Canadians had little or no confidence in the RCMP, compared to 37 per cent of Canadians served by a provincial police service.[212] The study also found that the RCMP as a whole was less trusted compared to municipal police services or individual RCMP detachments.[212]

During the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, several witnesses described apathy or disrespect on the part of officers taking statements about violence against Indigenous women, while others said that some officers declined to take statements altogether.[213][23]

Depictions in media

[edit]In 1912, Ralph Connor's Corporal Cameron of the North-West Mounted Police: A Tale of the MacLeod Trail appeared, and became an international best-selling novel. Mounties fiction became a popular genre in both pulp magazines and book form. Among the best-selling authors who specialized in tales of the Mounted Police were James Oliver Curwood, Laurie York Erskine, James B Hendryx, T Lund, Harwood Steele (the son of Sam Steele), and William Byron Mowery.

In other media, a famous example is the radio and television series, Sergeant Preston of the Yukon. Dudley Do-Right (of The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show) is a 1960s example of the comic aspect of the Mountie myth, as is Klondike Kat, from Total Television. The Broadway musical and Hollywood movie Rose-Marie is a 1930s example of its romantic side. A successful combination was a series of Renfrew of the Royal Mounted boy's adventure novels written by Laurie York Erskine beginning in 1922 and running to 1941. In the 1930s Erskine narrated a Sgt Renfrew of the Mounties radio show and a series of films with actor-singer James Newill playing Renfrew were released between 1937 and 1940. In 1953 portions of the films were mixed with new sequences of Newill for a Renfrew of the Mounted television series.

Bruce Carruthers (1901–1953), a former Mounted Police corporal (1919–1923), served as an unofficial technical advisor to Hollywood in many films with RCMP characters.[214] They included Heart of the North (1938), Susannah of the Mounties (1939), Northern Pursuit (1943), Gene Autry and The Mounties (1951), The Wild North (1952), and The Pony Soldier (1952).

Contemporary culture

[edit]In 1959, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation aired R.C.M.P., a half-hour dramatic series about an RCMP detachment keeping the peace and fighting crime. Filmed in black and white, in and around Ottawa by Crawley Films, the series was co-produced with the BBC and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and ran for 39 episodes. It was noted for its pairing of Québécois and Anglo officers.

Canadians also poke fun at the RCMP with Sergeant Renfrew and his faithful dog Cuddles in various sketches produced by the Royal Canadian Air Farce comedy troupe. On That '70s Show Mounties were played by SCTV alumni Joe Flaherty and Dave Thomas. The British have also exploited the myth: the BBC television series Monty Python's Flying Circus featured a group of Mounties singing the chorus in "The Lumberjack Song" in the lumberjack sketch. The 1972–90 CBC series The Beachcombers features a character named Constable John Constable who attempts to enforce the law in the town of Gibsons, British Columbia. In comic books, the Marvel Comics characters of Alpha Flight are described on several occasions as "RCMP auxiliaries", and two of their members, Snowbird and the second Major Mapleleaf are depicted as serving members of the service. In the latter case, due to trademark issues, Major Mapleleaf is described as a "Royal Canadian Mountie" in the opening roll call pages of each issue of Alpha Flight he appears in.

Charles Bronson and Lee Marvin starred in the 1981 movie Death Hunt that fictionalized the RCMP pursuit of Albert Johnson. British comedian Tony Slattery appeared as 'Malcolm the Mountie' in a series of UK TV adverts for Labatt's in the early 1990s. In the early 1990s, Canadian professional wrestler Jacques Rougeau utilized the gimmick of "The Mountie" while wrestling for the WWF. He typically wore the Red Serge to the ring and carried a shock stick as an illegal weapon. As his character was portrayed as an evil Mountie, the RCMP ultimately won an injunction preventing Rougeau from wrestling as this character in Canada, though he was not prevented from doing so outside the country. He briefly held the Intercontinental Championship in 1992.