Royal Scots Greys

| Royal Regiment of Scots Dragoons Royal North British Dragoons Royal Scots Greys | |

|---|---|

Cap badge of the Scots Greys | |

| Active | 1678–1971 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Line Cavalry |

| Role | Armoured |

| Size | Regiment |

| Part of | Royal Armoured Corps |

| Garrison/HQ | Redford Barracks, Edinburgh |

| Nickname(s) | "Birdcatchers"[1] "The Bubbly Jocks"[1] |

| Motto(s) | Nemo me impune lacessit (Nobody touches me with impunity) Second to None |

| Colours | Blue facings with gold lace (for officers) or yellow lace (for other ranks) |

| March | Quick (band) – Hielan' Laddie Slow (band) – The Garb of Old Gaul; (pipes & drums) – My Home |

| Insignia | |

| Tartan |  |

The Royal Scots Greys was a cavalry regiment of the Army of Scotland that became a regiment of the British Army in 1707 upon the Union of Scotland and England, continuing until 1971 when they amalgamated with the 3rd Carabiniers (Prince of Wales's Dragoon Guards) to form the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

The regiment's history began in 1678, when three independent troops of Scots Dragoons were raised. In 1681, these troops were regimented to form The Royal Regiment of Scots Dragoons, numbered the 4th Dragoons in 1694. They were already mounted on grey horses by this stage and were already being referred to as the Grey Dragoons.

Following the formation of the united Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707, they were renamed The Royal North British Dragoons (North Britain then being the envisaged common name for Scotland), but were already being referred to as the Scots Greys. In 1713, they were renumbered the 2nd Dragoons as part of a deal between the commands of the English Army and the Scottish Army when the two were in the process of being unified into the British Army.[2] They were also sometimes referred to, during the first Jacobite uprising, as Portmore's Dragoons.[3] In 1877, their nickname was finally made official when they became the 2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys), which was inverted in 1921 to The Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons). They kept this title until 2 July 1971, when they amalgamated with the 3rd Carabiniers, forming the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

Origins of the Scots Greys

[edit]

The Royal Scots Greys began life as three troops of dragoons; this meant that while mounted as cavalry, their armament was closer to that used by infantry units. Troopers were equipped with matchlock muskets, sergeants and corporals with halberds and pistols; only the officers carried swords, though Lieutenants were armed with a partisan.[4] The original uniform called for the troopers to wear grey coats, but there is no record of any requirement that the horses be a particular colour.[5]

On 21 May 1678, two troops were raised by Captains John Strachan and John Inglis with a third under Captain Viscount Kingstoun added on 23 September. These were the first mounted units raised for the Crown in Scotland and were used by John Graham, Viscount Dundee to uphold the Episcopalian order by suppressing prohibited Presbyterian assemblies or Conventicles in South-West Scotland.[6] Some of the persecuted Presbyterian civilians took up arms to defend their Conventicles from the dragoons' attacks in June 1679, and this resulted in the Bothwell Bridge.[7]

In 1681, an additional three troops were raised and added to the existing three to create what became the Royal Regiment of Scots Dragoons. In this period, regiments were considered the personal property of their colonel and changed names when transferred. At senior levels in particular, ownership and command were separate functions; 'Colonel' usually indicated ownership, with operational command generally exercised by a lieutenant colonel.[8]

Charles II's commander in Scotland, Lieutenant-General Thomas Dalziel, 1599-1685 was appointed Colonel with Charles Murray, Lord Dunmore as Lt-Colonel.[9] Shortly after James II & VII became King in February 1685, a Scottish revolt known as Argyll's Rising broke out in June which was easily crushed: the regiment saw action against Argyll's army at Stonedyke near Dumbarton.[10] Dunmore became Colonel of the Regiment himself in 1685. The Lt-Colonel at this time was William Livingston, Viscount Kilsyth.[11]

Scotland grew increasingly restive in the period before the November 1688 Glorious Revolution and the regiment was employed in an ultimately vain attempt to stem the tide of rebellion. It arrived in London shortly before William of Orange landed but saw no fighting and in December, Dunmore was replaced as Colonel by Sir Thomas Livingstone, a Scot who had served William for many years and was related to Kilsyth.[12] Now officially known as Livingstone's Regiment of Dragoons, after loyally serving the Stuarts' Episcopalian Scottish government they were now part of the force used by Hugh Mackay to support William's new Presbyterian Scottish government and oppose erstwhile comrades who remained loyal to the Stuarts and rebelled against William and his government in the first Scottish Jacobite Rising of 1689-1692. As cavalry, their role was to secure the roads between Inverness and Stirling and so were not present at the Jacobite victory of Killiecrankie in July 1689. In 1692, William III confirmed the regiment's designation as 'Royal' and they were ranked as the 4th Dragoons.[13]

1693–1714: Grey Horses, Red Coats, and War of Spanish Succession

[edit]

When inspected by William III in 1693, it was noted the regiment was mounted on grey horses. One suggestion is these were inherited from the Dutch Horse Guards, who had returned to the Netherlands but this has not been confirmed.[14] The original grey coats were replaced with red, or scarlet, coats with blue facings, proclaiming the Scots Greys "Royal" status.[14]

Transferred to the Netherlands in 1694 during the Nine Years' War, they were used for reconnaissance duties, but did not see any significant actions during their three years on the continent.[14] Following the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, they were based in Scotland; after the War of the Spanish Succession began, they returned to Flanders in 1702 as part of Marlborough's army. They played an active role in the campaigns of 1702 and 1703, including the capture of a large shipment of gold in 1703.[15]

During Marlborough's march to the Danube in 1704, the Scots Greys served as part of Ross's Dragoon Brigade.[16] Used as dismounted infantry, they took part in the Battle of Schellenberg, then the Battle of Blenheim on 2 July 1704; despite being heavily engaged, they did not have a single fatality, though many were wounded.[15]

At the Battle of Elixheim in 1705, the Scots Greys participated in the massed cavalry charge which broke through the French lines.[17] At Ramillies in May 1706, as part of Lord Hays' brigade of dragoons, the regiment captured the colours of the elite Régiment du Roi.[18]

Renamed the Royal North British Dragoons, their next significant action was the Battle of Oudenarde.[18] At the Battle of Malplaquet in September 1709, they captured the standard of the French Household Cavalry; This was their last significant action prior to the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713.[18]

Following the 1707 Acts of Union, the English and Scottish military establishments were merged, causing debates over regimental precedence; this was connected to the price of commissions, seniority and pay. The Scots Greys were to be designated the first dragoon regiment and the Royal Scots the first regiment of infantry but having both Scots regiments first led to protests. A compromise was reached, whereby the English dragoon regiment was designated as the first, and the Scots Greys became the 2nd Royal North British Dragoons. [2] This was the origin of the motto Second to None.[19]

1715–1741 Home Service and Jacobites

[edit]

Once back in Britain, the Scots Greys returned to Scotland where they helped police the countryside. In 1715, the Earl Mar declared for the "Old Pretender", James Stuart, sparking the Jacobite rising. Remaining loyal to the Anglo-German king, the Scots Greys were active in putting down the uprising. This included taking part at the Battle of Sheriffmuir on 13 November 1715. There the Scots Greys, under the Duke of Argyll, were stationed on the right of the Government forces.[20][21] Also known at that time as Portmore's Dragoons, the Scots Greys initially attacked the left flank of the Jacobite army. Advancing around a bog, which the highlanders had thought would protect their flank, the Scots Greys surprised the highlanders, making repeated charges into disordered ranks of the Jacobite infantry.[3] The Scots Greys continue to pursue the shattered left wing of the Jacobite force as it fled for nearly two miles until it was blocked by the river Allan. Unable to fall back, disorganised, they were easy targets for the Scots Greys' dragoons. It is reported that the Duke of Argyll was said to cry out to "Spare the poor blue bonnets!". However, little quarter was given by Scots Greys to any group trying to rally that day.[3] The rest of the royal forces were not as successful. The Jacobites managed to rout the left wing of the Royal army, the day ending in a tactical standoff.[2]

Although the fighting was indecisive, the battle had halted the Jacobites' momentum. For the next four years, the Scots Greys continued to suppress Jacobite supporters in Scotland.[21] With the final end of the First Jacobite rising in 1719, the Scots Greys went back to their traditional role: policing Scotland. The next 23 years passed relatively uneventfully for the regiment.[2]

War of the Austrian Succession

[edit]

During the 1740 to 1748 War of the Austrian Succession, 'British' forces served on behalf of Hanover until 1744. The Scots Greys transferred to Flanders in 1742 and garrisoned the area around Ghent.[2] The regiment fought at Dettingen in June 1743, now chiefly remembered as the last time a British monarch commanded troops in battle.[22] An attempt by the Allies to relieve Tournai led to the May 1745 Battle of Fontenoy; this featured a series of bloody frontal assaults by the infantry and the cavalry played little part, with the exception of covering the retreat.[23]

When the 1745 Rising began in July many British units were recalled to Scotland but the regiment remained in Flanders, fighting at the Battle of Rocoux on 11 October 1746, a French tactical victory. After Culloden, Cumberland and other British units returned to the Low Countries, in preparation for the 1747 campaign.[24]

The French won another tactical victory at Lauffeld on 2 July, where the Scots Greys took part in Ligonier's charge, one of the best known cavalry actions in British military history. This enabled the rest of the army to withdraw but Ligonier was taken prisoner and the Scots Greys lost nearly 40% of their strength.[25] By the time it was back to full strength, the 1748 Peace of Aix-la-Chappelle ended the war and the Scots Greys returned to Britain.[26]

Seven Years' War

[edit]The Scots Greys passed the seven years between the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle and the start of the Seven Years' War moving from station to station within Great Britain. The years passed relatively uneventfully for the regiment. The major development during this period was the addition of a light company to the Scots Greys in 1755.[27]

However, soon after the light company was raised, with Britain entering into the Seven Years' War, it was detached from the Scots Greys and combined with the light companies of other cavalry regiments to form a temporary, separate light battalion. This light battalion would be employed raiding the French coast.[26] One of the most notable raids was the attack on St. Malo from the 5 to 7 June 1758. The raid resulted in the destruction of the shipping at St. Malo.[28]

The balance of the regiment was transferred to Germany, where it joined the army commanded by Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick. Assigned to the cavalry under the command of Lord George Sackville, the Scots Greys arrived in Germany in 1758.[28] The following year, the Scots Greys took part in the Battle of Bergen on 13 April 1759. There, the forces of Britain, Hanover, Brunswick, and Hesse-Kassel were defeated, leaving the cavalry, including the Scots Greys, to cover the retreat. Because of the rear-guard action by the British cavalry, the army was able to survive to fight again later that year near Minden.[26]

Reeling after the defeat at Bergen, the British army and its allies reformed and engaged in a series of manoeuvres with the French armies. Eventually, the two forces collided on 1 August 1759 at the Battle of Minden.[29] The Scots Greys, still part of Sackville's command, were held back due to Sackville's delay. Eventually, while Sackville consulted with his superiors, his deputy, on his own initiative, finally ordered the Scots Greys and the rest of the cavalry forward. However, when Sackville returned, he countermanded the order and the cavalry held its place.[30] Once the battle appeared won, with the French retreating, the Scots Greys and the rest of the cavalry pressed the pursuit of the retreating French army.[31]

With Sackville sacked as commander of the British cavalry on the continent and court-martialed for his actions at Minden, the Scots Greys and the rest of the British cavalry came under the command of Marquess of Granby.[32] The following year, 1760, saw the British cavalry more aggressively led at the Battle of Warburg. There, on 31 July 1760, the Scots Greys participated in Granby's charge, which broke the French left flank and then defeated the counter-charge of the French cavalry.[31] Three weeks later, the Scots Greys, along with the Inniskilling Dragoons, met with the rearguard of the French forces near the town of Zierenberg. There the dragoons, supported by some British grenadiers, encountered a French cavalry force covering the retreat. Two squadrons of the Scots Greys charged four squadrons of French cavalry.[31] The Scots Greys and Inniskillings routed the French, sending them in a disorderly retreat into the town of Zierenberg. Soon after, infantry was brought up to storm the town; the town and the survivors of the Scots Greys' attack were captured.[33]

The Scots Greys began the following year by conducting patrols and skirmishing with French troops. Eventually, the Scots Greys were with the main army under Brunswick at the Battle of Villinghausen on 15–16 July 1761.[31]

The start of 1762 found the Scots Greys again raiding and clashing with French cavalry along the Hanoverian frontier. With the war approaching the end, the French decided to make one last concerted effort to overrun Hanover. At the same time, Brunswick, still commanding the Anglo-Hanoverian-Brunswick-Hessian forces in western Germany, wanted to take the initiative once the campaign season arrived. The two forces met at the castle of Wilhelmsthal near Calden.[34] Still attached to Granby's command, the Scots Greys were present for the Battle of Wilhelmsthal, on 24 July 1762. As the French centre gave way, the Scots Greys were ordered to exploit the victory. The Scots Greys drove the French forces through the village of Wilhelmsthal, capturing many prisoners and part of the baggage train.[31]

The Battle of Wilhemlstahl was to be the Scots Greys' last major engagement of the war. The following year, the French and British concluded the Treaty of Paris ending the hostilities, for the moment, between the two. With the end of the fighting, the Scots Greys returned home to Great Britain via the low countries.[35]

1764–1815

[edit]Home service and changes

[edit]Between 1764 and 1815, the Scots Greys remained on home service. Unlike many of the other regiments of British cavalry, they did not see any combat during the American Revolutionary War. Also, except for the Flanders Campaign of 1793–94, they saw no other active service during the French Revolutionary or Napoleonic Wars until the Waterloo Campaign of 1815. For most of the 20 years following the Seven Years' War the Scots Greys remained in Scotland and England.[36]

During this time, however, change was happening to the Scots Greys. Through a series of changes in uniform and equipment, the regiment began to be identified more as cavalry, rather than as mounted infantry. Drummers, an instrument of the infantry, were replaced with trumpeters, as was standard for cavalry regiments, in 1766.[37] Two years later, the Scot Greys traded in their mitre-style grenadier cap for the tall bearskin hat that would remain a part of the regiment's uniform until its amalgamation in 1971.[38] During this period, the Scots Greys also underwent an organizational change. Although deemed to be a heavy dragoon unit, each troop of the regiment was reorganised to include a detachment of light dragoons. These light dragoons were mounted on lighter, faster horses than the rest of the regiment. However, this increase in strength was soon lost, as the light troops of Scots Greys and other heavy dragoon regiments of the British Army were combined to form a new regiment, the 21st (Douglas's) Light Dragoons, in 1779.[39]

Campaign in the Low Countries

[edit]With the French Revolution in 1789, and the increasing tensions between Great Britain and Revolutionary France, the Scots Greys were brought up to strength and then expanded with four new troops to nine troops of dragoons, each of 54 men, in 1792 in anticipation of hostilities.[40] Four troops of the Scots Greys were alerted for possible foreign deployment in 1792 and were transported to the continent in 1793 to join the Duke of York's army operating in the low countries.[41] The Scots Greys arrived in time to participate in the siege of Valenciennes and then the unsuccessful siege of Dunkirk.[40]

Following the failure of the siege, the Scots Greys were employed as part of the screen for the Duke of York's army, skirmishing with French forces.[42] The next significant action for the Scots Greys occurred at Willems 10 May 1794 on the heights near Tournai. There the Scots Greys, brigaded with the Bays and the Inniskillings, charged the advancing French infantry. The French infantry, upon seeing the threat of the cavalry formed into squares. The Scots Greys charged directly into the nearest of the squares. The charge broke the formed infantry square, a remarkable feat. The breaking of the first square demoralised the other French infantry, allowing the Bays and the Inniskillings to break those squares as well.[43] In exchange for 20 casualties, the Greys had helped rout three battalions and capture at least 13 artillery pieces.[42] This would be the last time that British cavalry, alone without artillery support, would break an infantry square until the Battle of Garcia Hernandez in 1812.[43]

Despite the victory before Tournai, the Allied Army would be defeated at the Battle of Tourcoing on 18 May 1794. From then on, the British Army would be retreating in the face of the French Army. During the retreat, the Scots Greys were active in covering the British forces retreat through the low countries and into Hanover.[42] By the spring of 1795, the Army reached Bremen, in Hanover, and was embarked on ships to return to England. The four troops of Scots Greys arrived in England in November 1795, allowing the regiment to be reunited.[43] The ninth troop was disbanded when the regiment was reunited.[42]

Despite their exploits in the low countries, and the fact that Britain would be heavily engaged around the globe fighting Revolutionary and, later, Napoleonic France, the Scots Greys would not see action until 1815.[44]

Waterloo

[edit]

This changed when news of Napoleon's escape from Elba reached Britain. The Scots Greys, which had been reduced in size because of the end of the Peninsular War, were expanded. This time, there would be 10 troops of cavalry, a total of 946 officers and men, the largest the regiment had ever been until that time.[45] Six of the ten troops were sent to the continent, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel James Inglis Hamilton, to join the army forming under the command of the Duke of Wellington.[45] The Scots Greys, upon arrival in Ghent, were brigaded under the command of Major-General Ponsonby in the Union Brigade, with Royal Dragoons and the Inniskillings Dragoons.[46]

The Scots Greys, with the rest of the Union Brigade, missed the Battle of Quatre Bras despite a long day of hard riding. As the French fell back, the Scots Greys and the rest of the Union Brigade arrived at the end of their 50-mile ride.[47]

On the morning of 18 June 1815, the Scots Greys found themselves in the third line of Wellington's army, on the left flank.[48] As the fights around La Haye Sainte and Hougoumont developed, Wellington's cavalry commander, the Earl of Uxbridge, held the cavalry back. However, with the French infantry advancing and threatening to break the British centre. Uxbridge ordered the Household Brigade and the Union Brigades to attack the French infantry of D'Erlon's Corps. The Scots Greys were initially ordered to remain in reserve as the other two brigades attacked.[49]

As the rest of the British heavy cavalry advanced against the French infantry, just after 1:30 pm, Lieutenant-Colonel Hamilton witnessed Pack's brigade beginning to crumble, and the 92nd Highlanders falling back in disorder.[49] On his initiative, Hamilton ordered his regiment forward at the walk. Because the ground was broken and uneven, thanks to the mud, crops, and the men of the 92nd, the Scots Greys remained at the walk until they had passed through the Gordons. The arrival of the Scots Greys helped to rally the Gordons, who turned to attack the French.[49] Even without attacking at a full gallop, the weight of the Scots Greys charge proved to be irresistible for the French column pressing Pack's Brigade. As Captain Duthilt, who was present with de Marcognet's 3rd Division, wrote of the Scots Greys charge:

Just as I was pushing one of our men back into the ranks I saw him fall at my feet from a sabre slash. I turned round instantly – to see English cavalry forcing their way into our midst and hacking us to pieces. Just as it is difficult, if not impossible, for the best cavalry to break into infantry who are formed into squares and who defend themselves with coolness and daring, so it is true that once the ranks have been penetrated, then resistance is useless and nothing remains for the cavalry to do but to slaughter at almost no risk to themselves. This is what happened, in vain our poor fellows stood up and stretched out their arms; they could not reach far enough to bayonet these cavalrymen mounted on powerful horses, and the few shots fired in chaotic melee were just as fatal to our own men as to the English. And so we found ourselves defenceless against a relentless enemy who, in the intoxication of battle, sabred even our drummers and fifers without mercy.[50]

A lieutenant of the 92nd Highlanders who was present would later write, "the Scots Greys actually walked over this column".[51]

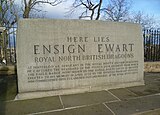

As the Scots Greys waded through the French column, Sergeant Charles Ewart found himself within sight of the eagle of 45e Régiment de Ligne (45th Regiment of the Line). With a chance to capture the eagle, Ewart fought his way towards it, later recounting:

One made a thrust at my groin – I parried it off and ... cut him through the head. one of their Lancers threw his lance at me but missed ... by my throwing it off with my sword ... I cut him through the chin and upwards through the teeth. Next, I was attacked by a foot soldier, who, after firing at me charged me with his bayonet, but ... I parried it and cut him down through the head.[53]

With the eagle captured, Sergeant Ewart was ordered to take the trophy off, denying the French troops a chance to recapture their battle standard. In recognition of his feat, he was promoted from sergeant to ensign.[54]

Having defeated the column and captured one of its battle standards, the Scots Greys were now disorganised. Neither Ponsonby nor Hamilton were able to effectively bring their troopers back under control. Rather than being able to reorganise, the Scots Greys continued their advance gaining speed, eventually galloping, and now aimed at Durutte's division of infantry.[55] Unlike the disordered column that had been engaged in attacking Pack's brigade, some of Durutte's men had time to form square to receive the cavalry charge.[55] The volley of musket fire scythed through the Scots Greys' ragged line as they swept over and round the French infantry, unable to break them. Colonel Hamilton was last seen during the charge, leading a party of Scots Greys, towards the French artillery.[56] However, in turning to receive the Scots Greys' charge, Durutte's infantry exposed themselves to the 1st Royal Dragoons. The Royal Dragoons slashed through them, capturing or routing much of the column.[57]

Having taken casualties, and still trying to reorder themselves, the Scots Greys and the rest of the Union Brigade found themselves before the main French lines.[58] Their horses were blown, and they were still in disorder without any idea of what their next collective objective was. Some attacked nearby gun batteries of the Grande Battery, dispersing or sabring the gunners.[59] Disorganized and milling about the bottom of the valley between Hougoumont and La Belle Alliance, the Scots Greys and the rest of the British heavy cavalry were taken by surprise by the counter-charge of Milhaud's cuirassiers, joined by lancers from Baron Jaquinot's 1st Cavalry Division.[60]

As Ponsonby tried to rally his men against the French cuirassers, he was attacked by Jaquinot's lancers and captured. A nearby party of Scots Greys saw the capture and attempted to rescue their brigade commander. However, the French soldier who had captured Ponsonby executed him and then used his lance to kill three of the Scots Greys who had attempted the rescue.[58] By the time Ponsonby died, the momentum had entirely returned in favour of the French. Milhaud's and Jaquinot's cavalrymen drove the Union Brigade from the valley. The French artillery added to the Scots Greys' misery.[56]

The remnants of the Scots Greys retreated to the British lines, harried by French cavalry. They eventually reformed on the left, supporting the rest of the line as best they could with carbine fire. In all, the Scots Greys suffered 104 dead and 97 wounded and lost 228 of the 416 horses. When they were finally reformed, the Scots Greys could only field two weakened squadrons, rather than the three complete ones with which they had begun the day.[56]

Following the victory of Waterloo, the Scots Greys pursued the defeated French Army until Napoleon's surrender and final abdication. The Scots Greys would remain on the continent until 1816 as part of the army of occupation under the terms of the peace treaty.[56]

1816–1856: Years of peace and the Crimean War

[edit]Between 1816 and 1854, the Scots Greys remained in the British Isles. As they had done in the interludes between continental wars, they moved from station to station, sometimes being called upon to support local civilian authorities.[61]

The decades of peaceful home service were broken with the outbreak of war with Russia. Trying to prop up the Ottoman Empire, Britain, France, and Sardinia, mobilised forces to fight in the Black Sea. The allied nations agreed that the target of the expedition would be Sevastopol in the Crimea. Assigned to Brigadier-General Sir James Scarlett's Heavy Brigade of the Cavalry Division, the Scots Greys, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Griffith arrived in the Crimea in 1854.[62]

On 25 October 1854, the Heavy Brigade was part of a British force supporting the siege operations around Sevastopol. The British on the right flank of the siege lines were over extended, giving the Russian forces under General Pavel Petrovich Liprandi an opportunity to disrupt the British siege works and possible destroy their supply base at Balaclava.[63] With nearly 25,000 men, including 3,000 cavalry troopers formed in 20 squadrons and 78 artillery pieces, General Liprandi attacked the British positions.[64] To defend its supply base and siege lines, the British could counter with approximately 4,500 men and 26 artillery pieces.[65]

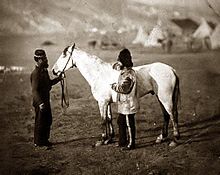

As the Russians attacked, the Scots Greys watched as the redoubts protecting the supply lines and Balaclava were overrun by the Russians.[66] They watched as the Russian force charged the 93rd Highlanders, only to be turned back by the "thin red streak tipped with a line of steel".[67]

Leading men into battle for the first time ever, Scarlett ordered his brigade to form two columns. The left column contained a squadron of the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons, followed by the two squadrons of the Scots Greys.[68] As they trotted to the assistance of the Campell's Highlanders, Scarlett was informed of additional Russian cavalry threatening his flank. Ordering the brigade to wheel about, the Scots Greys ended up in line with the Inniskilling Dragoons in the front row supported by the 5th Dragoon Guards.[68] Even with the Russian cavalry approaching, Scarlett waited patiently for his dragoons to be brought into formation rather than move in a disorganised formation.[69]

The approaching Russian cavalry was on the heights and numbered about 3,000 sabres. The Scots Greys and the rest of the British dragoons were waiting at the base of the heights, and totalled about 800 men.[69] Satisfied that his brigade was ready, Scarlett finally sounded the advance. Although Scarlett had spent precious minutes ordering his line, it soon proved to be unwieldy, especially in the sector occupied by the Scots Greys, who had to pick their way through the abandoned camp of the Light Brigade. The Scots Greys, once clear of the Light Brigade's camp, had to speed up to catch Scarlett and his aides, who were more than 50 yards ahead of them.[70] For some reason, the Russian cavalry commander chose to halt up slope of the Heavy Brigade, choosing to receive the charge at a halt.[71]

Scarlett and his command group, two aides and a trumpeter, were the first to reach the Russian cavalry. The rest of the brigade followed closely. As they neared the Russian line, they started to take carbine fire, which killed the Scots Greys' commander and took the hat off of its executive officer.[72] The Scots Greys finally came abreast of the Inniskillings just short of the Russians and the two regiments finally were able to gallop.[71] As the Inniskillings shouted their battle cry, Faugh A Ballagh, observers reported that the Scots Greys made an eerie, growling moan.[73] The Scots Greys charged through the Russian cavalry, along with the Inniskilings, and disappeared into the melee among the mass of Russian cavalry. With both forces disordered by the charge, it became clear to the regimental adjutant of the Scots Greys that, to avoid being overwhelmed by Russian numbers, the Scots Greys had to reform.[74] Pushed back from the centre of the mass, the Scots Greys reformed around the adjutant and drove again into the Russian cavalry. Seeing that the Scots Greys were again cut off, the Royal Dragoons, finally arriving to the fight after disobeying Scarlett's order to remain with the Light Brigade, charged to their assistance, helping to push the Russians back.[75] Amid the hacking and slashing of the sabre battle, the Russian cavalry had had enough, and retreated back up the hill, pursued for a short time by the Scots Greys and the rest of the regiments.[76]

The entire encounter lasted approximately 10 minutes, starting at 9:15 and ending by 9:30 am. In that time, in exchange for 78 total casualties, the Heavy Brigade inflicted 270 casualties on the Russian cavalry, including Major-General Khaletski.[76] More importantly, the Scots Greys helped rout a Russian cavalry division, ending the threat to Campbell's Highlanders, and with it the threat to the British supply base. With the rest of the Heavy Brigade, the Scots Greys could only look on as Lord Cardigan lead the Light Brigade on their ill-fated charge. As the Scots Greys returned to the British lines, they passed Colonel Campbell and the 93rd Highlanders. Campbell called out to the Scots Greys, "Greys, gallant Greys, I am sixty-one years of age, but were I young again, I should be proud to serve in your ranks."[73] Not only did Campbell recognise their achievement, so did the Crown. Two members of the Scots Greys, Regimental Sergeant Major John Grieve and Private Henry Ramage, were among the first to be awarded the Victoria Cross for their actions on 25 October.[77] For the rest of the war, the Heavy Cavalry, including the Scots Greys, had little to do.[78]

1857–1905: Home service, Egypt, and the 2nd Anglo-Boer War

[edit]

By 1857, the regiment was back in Britain, returning to its peacetime duties in England, Scotland and Ireland for the next fifty years of service without a shot being heard in anger.[79] After years of being known as the Scots Greys, though official designated as the 2nd Royal North British Dragoons, their nickname was made official. In 1877, the regiment was retitled as 2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys).[78]

Although individual members of the regiment on secondment to other units may have seen action, the regiment as a whole did not see active service until the start of the Anglo-Boer War. The largest detachment of the Scots Greys to see action were the two officers and 44 men who were sent to join the Heavy Camel Regiment during the expedition to relieve Gordon at Khartoum. They saw action at the Battle of Abu Klea, where they suffered thirteen killed in action, and another three who died of disease.[80]

In 1899, the regiment's years of peace ended with the start of the Second Anglo-Boer War. That year, the Scots Greys, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel W.P. Alexander, were ordered to Cape Town to join the Cavalry Division being formed.[81] In the years since Balaclava, much had changed about warfare. Gone were the red coats and bearskin shakos. The Scots Greys would now fight wearing khaki. In fact, with the popularity of wearing khaki that accompanied the start of the Boer War, the Scots Greys went so far as to dye their grey mounts khaki to help them blend in with the veldt.[82]

The regiment arrived in the Cape Colony in December 1899 and was put to work guarding the British lines of communication between the Orange and Modder rivers.[83] When Lord Roberts was prepared to begin his advance, the Scots Greys were attached to the 1st Cavalry Brigade under Brigadier General Porter.[83] While serving under Porter, the Scots Greys were reinforced by two squadrons of Australian horsemen.[84]

Once Roberts' offensive began, the Scots Greys took part in the relief of Kimberly. With Kimberly relieved, the Scots Greys were engaged in the fighting during the advance to Bloemfontein and later Pretoria, including the Battle of Diamond Hill.[85]

Following the capture of Pretoria, the Scots Greys were sent to liberate British prisoners. The POW's being held at Waterval POW camp, the same one where those captured in the Jameson Raid had been held.[86] As the Scots Greys approached, prisoner lookouts at the camp spotted the dragoons when they moved through Onderstepoort. As word spread through the camp, the British prisoners over-powered the guards, mostly men either too old or too young to be out on commando, pushed their way out of confinement to meet with the Scots Greys.[87] Although the camp guards were easily overcome, and most likely unknown to the British forces and prisoners, Koos de la Rey and his men were positioned to try and prevent the rescue of the British prisoners.[86] De la Rey ordered warning shells fired, trying to keep the prisoners in their prison camp. Faced with the approaching Scots Greys and the prisoners, De la Rey opted to not do more and instead ordered a retreat rather than fight a battle over the prison camp.[88]

The fall of Pretoria was also the end of the second phase of the war. With the end of formal fighting, and the start of third phase of the Boer War, the guerrilla campaign by the Boers, the Scots Greys were on the move constantly.[85]

Among the detachments was a squadron was left at Uitval (also known as Silkaatsnek) under the command of Major H. J. Scobell. There they were eventually joined by five companies from the 2nd battalion, the Lincolnshire Regiment, with a section of guns from O Battery, RHA.[89] While Scobell had kept a strong picket line to watch for Boer commandos, this was changed when he was superseded as the commander of the garrison and the Scots Greys came under the command of an infantry colonel.[90] This decrease in pickets allowed a force of Boer commandos to attack the outpost on 10 July 1900. Most of the squadron was captured during the disaster that ensued. The defeat allowed the Boers to hold Silkaatsnek.[91]

Following the disaster at Silkaatsnek, the Scots Greys were concentrated and returned to operating with the 1st Cavalry Brigade. From February to April 1901, the Scots Greys and 6th Dragoon Guards were sent on a sweep from Pretoria to east of Transvaal. In the process, they captured or destroyed large amounts of Boer war stocks, including nearly all of the remaining artillery.[85] Following that success, the Scots Greys and 6th Dragoon Guards were sent to sweep the guerrillas from the valley of the Vaal and into the Western Transvaal. There, they received word of the defeat of Benson's column at Battle of Bakenlaagte on 30 October 1901.[85] Reinforced by the 18th Hussars, 19th Hussars, and a detachment of mounted Australians, the reinforced brigade chased after the Boers, killing a number of those who had participated in the fighting at Bakenlaagte.[85]

The Scots Greys would continue fighting to suppress the guerrilla campaign. The most notable capture made by the regiment was that of Commandant Danie Malan.[92] Eventually, the last of the "bitter enders" in the Boer camp agreed to peace, with the formal end of the conflict happening on 31 May 1902. The Scots Greys remained for three more years, helping to garrison the colony, operating out of Stellenbosch, before returning home to Britain in 1905.[92]

The Great War

[edit]During the inter-war years, the Scots Greys were re-equipped and reorganised based on the experience of Boer War. Lee–Enfield rifles and new swords were introduced as the British Army debated what the role of cavalry would be in the coming war. In 1914, the Scots Greys were organised as a regiment of three squadrons. Each squadron was made up of four troops with 33 men each.[93] When war did come, in August 1914, the Scots Greys were assigned to the 5th Cavalry Brigade commanded by Brigadier P.W. Chetwode.[92]

Initially, the 5th Cavalry Brigade operated as an independent unit under control of the BEF. However, on 6 September 1914, it was assigned to Brigadier-General Gough's command. When Gough's independent command was expanded to a division, the formation was redesignated as the 2nd Cavalry Division. The Scots Greys and the other cavalry regiments of the 5th Brigade would remain with the 2nd Cavalry Division for the rest of the war.[94]

1914: Mons, the Retreat, the Marne, the Aisne

[edit]The regiment landed in France on 17 August 1914. Soon after arriving in France, staff of the BEF issued a directive ordering the Scots Greys to dye their horses. The reason was partly because the grey mounts made conspicuous targets, but was also partly based on the fact that the all grey mounts made the regiment distinctive and therefore easier to identify. For the rest of the war, the grey horses of the regiment would be dyed a dark chestnut.[95]

First contact with the German army came on 22 August 1914 near Mons. The Scots Greys, fighting dismounted, drove off a detachment from the German 13th Division. The German infantry reported that they fell back because they had encountered a brigade.[96] As it became apparent that the B.E.F. could not hold the position against the German onslaught, the Scots Greys became part of the rear guard, protecting the retreating I Corps.[95] In the aftermath of the Battle of Le Cateau, the Scots Greys, with the rest of the 5th Cavalry Brigade, helped to temporarily check the German pursuit at Cerizy, on 28 August 1914.[97]

Once the B.E.F. was able to reorganise and take part in the Battle of the Marne, in September 1914, the Scots Greys shifted from covering the retreat to screening the advance. Eventually, the advance of the B.E.F. halted at the Battle of Aisne, where British and German forces fought to standstill just short of the Chemin des Dames.[95]

1914: Race to the sea and First Ypres

[edit]After being pulled from the trenches at the Aisne, the Scots Greys were sent north to Belgium as part of the lead elements as the British and Germans raced towards the sea, each trying to outflank the other.[98] With the cavalry reinforced to Corps strength, the Scots Greys and the rest of the 5th Cavalry Brigade were transferred to the newly formed 2nd Cavalry Division.[99]

As the front became more static, and the need for riflemen on the front line more pressing, the Scots Greys found themselves being used almost exclusively as infantry through the Battles of Messines and Ypres. The regiment was almost continuously engaged from the start of the First Battle of Ypres until its end.[98]

1915–1916: Trench warfare

[edit]

The Scots Greys rotated back into the trenches in 1915. Due to the shortage of infantry, the regiment continued to fill the gaps in the line, fighting in a dismounted role. The regiment remained on line for all but seven days of the Second Battle of Ypres. The losses in that battle would force the Scots Greys into reserve for the rest of the year.[98] According to a report in Scottish newspapers of the time it was decided to paint the horses khaki as their grey coats were too visible to German gunners. This gave rise to a comic poem printed at the time, of which this is the first verse:

O wae is me my hert is sair, tho but a horse am I.

My Scottish pride is wounded and among the dust maun lie.

I used to be a braw Scots grey but now I'm khaki clad.

My auld grey coat has disappeared, the thocht o't makes me sad.

By January 1916, the Scots Greys were back in action, albeit in a piecemeal fashion. With the Kitchener Armies still not fully ready, men were still needed for the front. Like the other cavalry regiments, the Scots Greys contributed a troop to the front. In two months of action, this line troop was active in raids and countering raids by the German army.[98]

With the arrival of the Kitchener Armies, the Scots Greys were concentrated again in preparation of the forthcoming summer offensive. The 2nd Cavalry Division became the reserve for General Plumer's Second Army. Mounted, the Scots Greys were held in readiness to exploit a breakthrough that never came during the Battle of the Somme.[98]

As the war continued, it became apparent that more mobile firepower was needed at all levels of the British Army. Accordingly, the Scots Greys were expanded to include a machine gun squadron.[101]

1917: Arras and Cambrai

[edit]As the war progressed, British generals still hoped to use the Scots Greys and other cavalry regiments in their traditional roles. The Battle of Arras would demonstrate the futility of that hope.[101]

Beginning in April, the Scots Greys were engaged in action around the town of Wancourt. In three days of fighting, in an action that would become known as the First Battle of the Scarpe, the regiment suffered heavy casualties among its men and horses.[102] After a short period to refit, the Greys drew the assignment of raiding the German positions at Guillermont Farm. The raid succeeded, with the Scots Greys killing 56 and capturing 14 with negligible loss to themselves.[101]

In November 1917, the Scots Greys saw a glimpse of their future when they moved to support the armoured attack at the Battle of Cambrai. Initially intended to be part of the exploitation force, as at the Battle of the Somme, the plan failed to develop the type of break through which could be exploited by the cavalry. As the fighting bogged down, the Scots Greys once again found themselves fighting on foot in an infantry role. Part of the reason that the Scots Greys were unable to advance as cavalry was because the bridge that was crucial to the advance was accidentally destroyed when the tank crossing it proved to be too heavy.[103] Unable to advance mounted, the Scots Greys were committed as infantry to the battle.[101]

1918: St. Quentin, retreat, 100 Days

[edit]After the winding down of the battles of 1917, the Scots Greys found themselves near the St. Quentin canal. There, they witnessed the German offensive forcing their way across the canal. Although the Scots Greys held their positions, they were soon in danger of being flanked. After almost three years of static warfare, the rapidity of the German advance caught the regiment flat flooted as the German attacks penetrated the Scots Greys position.[101] In the confusion of the retreat, detachments of the Scots Greys became lost and ended up serving with other regiments of the 5th Cavalry Brigade, fighting rearguard actions as the B.E.F. retreated. Once the Michael Offensive began to grind down in April, the Scots Greys, along with the other cavalry regiments, were able to be withdrawn from the line to refit and reorganise.[101]

Between May and June 1918, the Scots Greys were held in reserve. However, in August, the Scots Greys was brought forward for the Battle of Amiens.[104] Still part of the 2nd Cavalry Division, the Scots Greys moved in support of the Canadian Corps' attack on Roye.[105]

With the victory at Amiens, the B.E.F. began its long-awaited final offensive. During this first month of the offensive, August to September 1918, the Scots Greys rarely operated as a unit. Instead, detachments of the Scots Greys were engaged in a variety of traditional cavalry duties. This included scouting, liaison duties and patrolling.[101] As the B.E.F. approached the Sambre river, the Scots Greys were used to probe the available river crossings. However, just as they did, many dragoons of the Scots Greys began to fall ill from influenza. Within a few days, due almost solely to the influenza outbreak, the regiment could muster only one composite company of men healthy enough to fight.[106]

At the time of the Armistice, the Scots Greys were at Avesnes. To enforce the terms of the Armistice, the Scots Greys were ordered to cross into Germany, arriving there on 1 December 1918. However, although they would be here to police the terms of the armistice until a final treaty could be completed, they were almost immediately dismounted. By the beginning of 1919, the Scots Greys were reduced to 7 officers and 126 other ranks.[106] This was approximately the size of one of its pre-war squadrons.[93] After almost five years of service on the continent, the Scots Greys returned home to Britain on 21 March 1919 via Southampton.[106]

1919–1939: Inter-war years

[edit]For the next year, the Scots Greys remained in Britain. While there, the regiment was once again renamed. This time they were designated the "Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons)".[107] Although tanks had been introduced during the First World War, many senior officers believed that the horse still had a place on the battlefield. Consequently, the Scots Greys retained their horses when they were sent on to their first peacetime deployment "East of Suez". In 1922, the Scots Greys arrived in India, where they would serve for the next six years.[107]

Upon returning to Great Britain, the Scots Greys found themselves subject to the problems that the rest of the British Army were going through in that era. In 1933, the regiment took part in a recruiting drive by conducting a march through Scotland, including a three-day traverse of the Cairngorm Mountains to get better publicity.[107] Although budgets were lean, the Scots Greys, like other British cavalry regiments, were finally re-equipped. Each troop would now contain an automatic weapons section.[107]

Still mounted on horses, the Scots Greys received orders for Palestine in October 1938. There they took part in suppressing the later stages of Arab Revolt. Much of the time, the Scots Greys were engaged in keeping the peace between the Jewish settlers and the Arabs.[107]

Second World War

[edit]1939–1941: Palestine and Syria

[edit]Still stationed in Palestine, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel H. N. Todd, the Scots Greys were brought up to war strength following the declaration of war against Germany. Although the German blitzkrieg attacks in Poland, France and the Low Countries demonstrated that the tank was now the dominant weapon, the Scots Greys continued to be equipped with horses.[107]

As the B.E.F. fought in France in 1940, the Scots Greys were retained in the Middle East to police the Mandate. In fact the last mounted cavalry charge on horseback by the Scots Greys occurred in February 1940, when the regiment was called to quell Arab rioters.[107]

At first, the Scots Greys were transformed into a motorised regiment, using wheeled vehicles. Elements of the Scots Greys and Staffordshire Yeomanry formed a composite cavalry regiment assigned to reinforce the divisional cavalry element for Operation Exporter, the invasion of Vichy-held Syria and Lebanon. The remainder of the regiment remained in Palestine, operating in the vicinity of Jerusalem.[108] The composite Grey-Stafford regiment took part in most of the battles of the campaign, including the Battle of Kissoué, where it held off a counter-attack by Vichy French armour.[109]

A final review of the Scots Greys as a cavalry regiment occurred at Nablus in the Palestine mandate once the campaign in Syria and Lebanon was complete. Soon after this final review, the horses were traded in and then they who had spent their lives as dragoons were retrained to act as drivers, loaders, and gunners for tanks. Now designated as an armoured regiment, they received their first tanks in September 1941. Initially, the Scots Greys trained on the Stuart tank.[110]

1942–1943: Egypt, Libya, Tunisia

[edit]

With the conversion to armour complete, the Scots Greys were transferred to the Eighth Army. Once in Egypt, their new Stuart tanks were immediately withdrawn and the regiment spent time near Cairo learning to operate the Grant.[110]

Although combat ready, the Scots Greys did not participate in the fighting around Tobruk in the late spring and summer of 1942. Because so many other armoured units were mauled in the fighting, the Scots Greys had to turn over their tanks to other units. In July 1942, the Scots Greys finally were committed to the fighting, equipped with a mixture of Grant and Stuart tanks. Unlike most tank units in the Eighth Army, which were either predominantly fielding heavy/medium tanks or light tanks, the Scots Greys field 24 Grants and 21 Stuarts.[111] Temporarily attached to the 22nd Armoured Brigade, the Scots Greys were placed with majority of the British heavy armour.[112] Initially held in reserve on Ruweisat Ridge, the Scots Greys conducted a successful counter-attack against the German forces to plug a hole that had been created by the German attack.[113] Attacking as though still a mounted regiment, the Scots Greys fought the Panzer IV's of the 21st Panzer Division, eventually driving them back.[114]

A month later, the Scots Greys were in action again at the Second Battle of El Alamein.[110] Now attached to the 22nd Armoured Brigade, part of the 7th Armoured Division.[112] As part of the 4th Armoured Brigade, the Scots Greys took part in the diversionary attack which pinned the 21st Panzer Division and Ariete Division in place while other elements of the Eighth Army executed the main attack to the north. the way through the minefields.[115] Once the break-out began, with Operation Supercharge, the Scots Greys, now back with the 4th Armoured Brigade, which was attached to the 2nd New Zealand Division, began attempted break-out.[116] In the course of their advance, the Scots Greys participated in the annihilation of the Ariete Division on 4 November 1942.[117] At Fuka, the Scots Greys found the division's artillery. Charging forward as if still mounted on horses, the Scots Greys captured eleven artillery pieces and approximately 300 prisoners in exchange for one Stuart put out of action.[115]

The Scots Greys continued their pursuit of the Panzer Army Africa for the next month and a half. The main problem for the regiment faced as it chased after Rommel's retreating army was the condition of its tanks. Some tanks were repairable, others had to be replaced from whatever was available.[117] By the end of the month, the Scots Greys were fielding 6 Grant, 17 Sherman, and 21 Stuart tanks. Beginning in the second week of December, the Eighth Army became engaged in what would develop into the Battle of El Agheila. On 15 December 1942, the Scots Greys became engaged in tank battle with elements of the 15th Panzer Division near the village of Nofilia. Due to breakdowns and losses along the way, the Scots Greys were reduced to 5 Grants and 10 Shermans. Leading the 4th Armour Brigade's advance, the Scots Greys entered the village, over-running the infantry defenders, capturing 250 men of the 115 Panzergrenadier Regiment.[116] Just as it was completing the capture of the prisoners, the Scots Greys encountered approximately 30 panzers of the 15th Panzer Division.[116] The tank engagement was inconclusive, with each side losing 4 tanks, although the Scots Greys were able to recover 2 of their damaged tanks.[118] The Germans withdrew as the 2nd New Zealand Division moved to the south, outflanking the 15th Panzer Division.[116]

As the pursuit continued, the Scots Greys saw little in the way of tank versus tank action while Rommel's army retreated into Tunisia. By January 1943, the decision was made to withdraw the Scots Greys from the front to refit the regiment.[115]

1943: Italy

[edit]

The Royal Scots Greys were re-equipped as an all-Sherman regiment, with Sherman II tanks. The regiment continued to refit through the short Sicilian campaign, not seeing action until it was part of the Salerno landings (Operation Avalanche), part of the Italian Campaign, in September 1943.[115] The regiment was assigned to 23rd Armoured Brigade, alongside 40th and 46th RTR. The 23rd was an independent brigade reporting directly to British X Corps, which was itself under command of the U.S. Fifth Army.[119]

Soon after landing, the Royal Scots Greys were in action against the German forces during the advance to Naples. Although the regiment was part of the 23rd Armoured Brigade, the regiment's three squadrons were split up to provide armour support for the three brigades (167th, 169th and 201st Guards) of the 56th (London) Infantry Division, nicknamed "The Black Cats".[120] Landing with the Black Cats of the 56th Division, the Scots Greys were instrumental in defeating the counter-attacks of Sixteenth Panzer Division.[121] Finally, on 16 September, the Scots Greys were committed to the fight as a regiment, helping to stop, and then drive back, the Twenty-Sixth Panzer Division, allowing X Corps to advance out of the beachhead.[122] The regiment would continue to participate in the Allied drive north, until it was brought to a halt at the Garigliano River. In January 1944, the regiment turned over its tanks to other units needing replacements and was transferred back to England.[115] Just before the regiment sailed, they were transferred back to the 4th Armoured Brigade.[123]

1944–1945: North-West Europe

[edit]The regiment spent the first half of the year refitting and training in preparation for the invasion of Europe. On 7 June 1944, the first three tanks of the regiment landed on Juno Beach.[115] As part of the Battle of Caen, the Scots Greys took part in the fighting for Hill 112.[124] During the fighting for Hill 112, the Scots Greys came to realise disparity between the Sherman II's and the latest German armour, including the new Panthers. In one incident, a 75mm equipped Sherman of the Scots Greys hit a Panther at 800 yards four times. All four rounds impacted harmlessly on the Panther's frontal armour.[125]

Once the breakthrough was achieved, the Scots Greys took part in the pursuit of the retreating German forces. The Scots Greys saw action at the Falaise pocket, the crossing of the Seine, and was one of the first regiments to cross the Somme River at the beginning of September 1944.[126] After crossing the Somme, the Scots Greys, along with the rest of the 4th Armoured Brigade, moved north into Belgium, near Oudenarde.[126]

In mid September, the Scots Greys took part in the Operation Market-Garden, in particular the fighting around Eindhoven where the 101st Airborne landed to capture the bridges.[127] The Scots Greys would operate in the Low Countries for the rest of the year. The regiment saw action in operations helping to capture Nijmegen Island, and the area west of the Maas. The regiment also helped to capture the Wilhelmina Canal and clear German resistance along the Lower Rhine to secure the allied flank for the eventual drive into Germany.[126][128]

After nearly six months of fighting in the low countries, the Scots Greys entered Germany as part of Montgomery's Operation Plunder offensive. On 26 February, the Scots Greys crossed into Germany.[129] Little more than a month later, the regiment was involved in the capture of Bremen.[126] On 3 April 1945, the Scots Greys came under the command of the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division, forming up in Neuenkirchen. On 5 April, the regiment supported the hard-fought breakout of the 156th (Scottish Rifles) Brigade, as they crossed the Dortmund-Ems Canal and went on to capture the district of Drierwalde. They continued to support the 52nd Division as they made their way across Germany towards Bremen, securing Hopsten, Recke, Voltage, Alfhausen, Bersenbrück, and Holdorf along the way.[130]

With Germany crumbling, Allied commanders began to become concerned with how far the Red Army was advancing into Western and Central Europe. To prevent possible post-war claims over Denmark, the Scots Greys and 6th Airborne Division were tasked with the job of extending eastwards past Lübeck. Despite having been in action for three months, the Scots Greys covered 60 miles (97 km) in eight hours to capture the city of Wismar on 1 May 1945.[131] The regiment captured the town just hours before meeting up with the Red Army.[131]

The final surrender by the surviving Nazi officials on 5 May 1945 marked the end of the war for the Scots Greys. With no further fighting in the regiment's near future, the Scots Greys immediately began collecting horses to establish a regimental riding school at Wismar.[131]

1946–1971: Post-War and Amalgamation

[edit]After the final surrender of Japan, the Scots Greys shifted to garrison duty. From 1945 until 1952, the regiment remained in the British sector of Germany as part of the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR), garrisoned at Osnabrück as part of 20th Armoured Brigade.[132][133] In 1952, the regiment deployed to Libya, joining the 25th Armoured Brigade.[132] The regiment returned to home service in 1955, rotating through barracks in Britain and Ireland before returning to Germany 1958 to rejoin the BAOR.[133]

In 1962, the Scots Greys were on the move again, this time deploying to help with the Aden Emergency. The regiment remained in Aden until 1963, helping to guard the border with Yemen.[134] After a year in the Middle East, the Scots Greys returned to Germany, where they would remain until 1969.[133]

In 1969, the Scots Greys returned home to Scotland for the last time as an independent unit. As part of the reductions started by the 1957 Defence White Paper, the Royal Scots Greys were scheduled to be amalgamated with the 3rd Carabiniers (Prince of Wales's Dragoon Guards). The amalgamation took place on 2 July 1971 at Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh. The amalgamated formation was christened The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards (Carabiniers and Greys).[131]

Regimental traditions

[edit]Regimental museum

[edit]The regimental collection is held by the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards Museum which is based in Edinburgh Castle.[135]

Scots Greys band

[edit]Unique among British cavalry regiments was that the Scots Greys fielded bagpipers. These bagpipers were initially formed by and paid for by the regiment because they were not authorised pipers on strength. At various times throughout the history of the regiment, there were pipers in the regiment, but these were unofficial. While stationed in India in the 1920s, the regiment fielded its first mounted pipers. At the end of the Second World War, the British Army was contracting from its wartime strength. Despite the contraction of some Scottish Territorial and Yeomanary units, some of the personnel were retained by the army and sent to various other units. As part of this, the Scots Greys received a small pipe band from one of these demobilised units.[136] King George VI took a particular interest in the Scots Greys' pipe band. His interest was so great that he took part in the design of the band's uniform, awarding them the right to wear the Royal Stuart tartan.[136]

The Scots Greys band over the years has acquired a few of its own traditions, which were specific to the band as opposed to the rest of the regiment. While the full dress of the rest of regiment required the wearing of a black bearskin headdress, the kettle drummers wore white bearskins. The tradition of the white bearskins is believed to have originated in 1887 ahead of the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. A common myth is that the adoption of white bearskin caps comes from Tsar Nicolas II, who was appointed Colonel-in-Chief of the regiment on his coronation in 1894, however pictures exist of the white bearskin caps being in use prior to this in addition to being disputed by the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards, who maintain the traditions of their antecedent regiments. [137][138][139] A tradition developed within the regiment of the Scots Greys band playing the Russian national anthem in the regiment's officers mess, in honour of Tsar Nicholas II.[140]

In addition to distinctive uniforms, the Scots Greys band was also entitled to certain other prerogatives. These included flying the sovereign's personal pipe banner, carried by the pipe major when the sovereign was present.[140]

An album called Last of The Greys by the Royal Scots Greys regimental band was released in 1972 – from which the track Amazing Grace went, astonishingly, to top of the "Top 40" charts on both sides of the Atlantic.[141][142] In the UK, the recording went to number one.[143] The successor formations to the Scots Greys continue to release albums today.[141]

Nicknames

[edit]Up until at least the Second World War, The Greys also had a popular, if somewhat derogatory, nickname of "The Bird Catchers", derived from their cap badge and the capture of the Eagle at Waterloo. Another nickname of the regiment was the "Bubbly Jocks", a Scots term meaning "turkey cock".[144]

Anniversaries and the loyal toast

[edit]Most regiments of the British Army have regimental anniversaries, usually commemorating a battle which the regiment distinguished itself. In the Scots Greys, the regiment annual commemorated its participation in the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June.[140]

The Scots Greys, along with certain other regiments of the British Army, handled the loyal toast differently. Since the Glorious Revolution, officers were required to toast the health of the reigning sovereign. Typically, this meant standing and giving a toast to the monarch. The Scots Greys, however, did not stand for the toast. It is said that this tradition of giving the loyal toast while seated started during the reign of George III. During his reign, George III would often dine with the regiment; however, because of his health, he was unable to stand during the toasts. Since he could not, he allowed the officers to remain seated during the loyal toasts.[140]

Motto

[edit]The Scots Greys had the motto "Second to none". It referred to their seniority in the British Army and their fighting prowess. Their official motto, however, was that of the Order of the Thistle; Nemo Me Impune Lacessit (No one provokes me with impunity).[144]

Uniform

[edit]Although the same basic uniform was worn by the heavy cavalry of the British Army at any given period, for centuries each regiment had its own distinctions and variations. The Scots Greys were no different. The most noticeable difference in the uniform of the Scots Greys was that the regimental full dress worn as general issue until 1914 included a bearskin cap. They were the only British heavy cavalry regiment to wear this fur headdress. Prior to receiving the bearskin, they were also unique among British cavalry regiments in wearing the mitre cap (sometimes referred to as a grenadier cap) instead of the cocked hat or tricorn worn by the rest of the British cavalry during the eighteenth century. The mitre cap dates back to the reign of Queen Anne, who awarded them this distinction after the Battle of Ramillies in 1706. An early form of the bearskin was adopted in 1768.[145]

Other regimental dress distinctions of the Scots Greys included a black and white zigzag "Vandyk" band on the No. 1 dress peaked caps of the regiment, metal insignia representing the White Horse of Hanover worn at the back of the bearskin, and the silver eagle badge worn to commemorate the capture of the French standard at Waterloo.[146]

Alliances

[edit]The Scots Greys had affiliations with the following units:[144]

Canada—2nd Dragoons

Canada—2nd Dragoons Canada—New Brunswick Dragoons

Canada—New Brunswick Dragoons Australia—12th Light Horse

Australia—12th Light Horse New Zealand—North Auckland Mounted Rifles

New Zealand—North Auckland Mounted Rifles New Zealand—New Zealand Scottish Regiment[147]

New Zealand—New Zealand Scottish Regiment[147]

Battle honours

[edit]

Battle honours of the Scots Greys:[144]

- War of Spanish Succession: Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, Malplaquet

- War of Austrian Succession: Dettingen

- Seven Years' War: Warburg, Willems

- Napoleonic Wars: Waterloo

- Crimean War: Balaclava, Sevastopol

- Second Boer War: South Africa 1899–1902, Relief of Kimberley, Paardeberg

- First World War: Retreat from Mons; Marne 1914; Aisne 1914; Ypres 1914, 1915; Arras 1917; Amiens; Somme 1918; Hindenburg Line; Pursuit to Mons; France and Flanders 1914–18. Mons; Messines 1914; Gheluvelt; Neuve Chapelle; St Julien; Bellewaarde; Scarpe 1917; Cambrai 1917, 1918; Lys; Hazebrouck; Albert 1918; Bapaume 1918; St Quentin Canal; Beaurevoir.

- Second World War: Hill 112; Falaise; Hochwald; Aller; Bremen; Merjayun; Alam el Halfa; El Alamein; Nofilia; Salerno; Italy 1943; Caen; Venlo Pocket; North-West Europe 1944-5; Syria 1941; El Agheila; Advance on Tripoli; North Africa 1942-3; Battipaglia; Volturno Crossing.

Colonels-in-Chief

[edit]The colonels-in-chief of the regiment were as follows:[148]

- 1894–1918: Emperor Nicholas II of Russia

- 1936–1952: King George VI

- 1952–1971: Queen Elizabeth II

Colonels of the regiment

[edit]

The colonels of the regiment were as follows:[148]

- from 1681 The Royal Regiment of Scots Dragoons

- 1681 Lieutenant-General Thomas Dalziel

- 1685 Colonel Lord Charles Murray

- 1688 Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Livingstone

- from 1694 The 4th Dragoons

- 1704 Brigadier-General Lord John Hay

- 1706 Field Marshal Lord John Dalrymple

- from 1707 The Royal North British Dragoons

- from 1713 2nd Dragoons

- 1714 General David, Earl of Portmore KT

- 1717 Lieutenant-General Sir James Campbell KB

- 1745 Field Marshal John, Earl of Stair KT

- 1747 Lieutenant-General John, Earl of Crawford

- 1750 General John, Earl of Rothes KT

On 1 July 1751, a royal warrant provided that, in future, regiments would not be known by their colonels' names, but by their "number or rank".

- from 1751 2nd Dragoons

- 1752 General John Campbell

- 1770 General William, Earl of Panmure

- 1782 Lieutenant-General George Preston; joined the regiment in 1739, reaching the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel; transferred to 17th Lancers as Colonel in 1770, then returned in 1782;[149][150]

- 1785 General James Johnston

- 1795 General Archibald, Earl of Eglinton

- 1796 Lieutenant-General Sir Ralph Abercromby KB

- 1801 General Sir David Dundas GCB

- 1813 General William John Kerr, 5th Marquess of Lothian, KT

- 1815 General Sir James Steuart, Bt., GCH

- 1839 General Sir William Keir Grant, KCB, KH

- 1852 Lieutenant-General Archibald Money, CB

- 1858 Lieutenant-General Arthur Moyses William Hill, 2nd Baron Sandys

- 1860 Lieutenant-General Sir Alexander Kennedy Clark-Kennedy, KCB, KH

- 1864 General Sir John Bloomfield Gough GCB

- from 1877 2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys)

- 1891 General George Calvert Clarke CB

- 1900 Lieutenant-General Andrew Nugent

- 1905 Major-General Andrew Smythe Montague Browne

- 1916 Field Marshal Sir William Robert Robertson, Bt., GCB, GCMG, GCVO, DSO

- from 1921 The Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons)

- 1925 Field Marshal Sir Philip Walhouse Chetwode, 1st Baron Chetwode, GCB, OM, GCSI, KCMG, DSO

- 1947 Brigadier George Herbert Norris Todd, MC

- 1958 Brigadier John Edmund Swetenham, DSO

- 1968–1971 Colonel Alexander George Jeffrey Readman, DSO

- from 1971 amalgamated with 3rd Carabiniers to form

References

[edit]- ^ a b Farmer, John S. (1984). The Regimental Records of the British Army. Bristol: Crecy Books. p. 23. ISBN 0-947554-03-3.

- ^ a b c d e Charles Grant and Michael Youens, Royal Scots Greys, (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, Ltd., 1972) p. 9

- ^ a b c Battle of Sheriffmuir at historynet.com retrieved on 1 November 2009

- ^ Almack 1908, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Grant and Youens 1972, p. 4.

- ^ Grant and Youens 1972, p. 3

- ^ Edward Almack, The History of the Second Dragoons: The Scots Greys, (London, 1908), pp. 6–8.

- ^ Guy, Alan (1985). Economy and Discipline: Officership and the British Army, 1714–63. Manchester University Press. p. 49. ISBN 0-7190-1099-3.

- ^ Edward Almack, The History of the Second Dragoons: The Scots Greys, (London, 1908), pp. 2–4.

- ^ "The 2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys)". British Empire. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ Almack, Edward (1908). The History of the Second Dragoons Royal Scots Greys (2010 ed.). Kessinger Publishing. pp. 17–18. ISBN 1120890209.

- ^ Edward Almack, The History of the Second Dragoons: The Scots Greys, (London, 1908), pp. 17–18.

- ^ Grant and Youens 1972, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Grant and Youens 1972, p. 6

- ^ a b Grant and Youens 1972, p. 7.

- ^ Higgins, David R. "Tactical File: The Famous Victory: Blenheim, 13 August 1704." Strategy & Tactics, Number 238 (September 2006)

- ^ Fortescue 1918, p.57

- ^ a b c Grant and Youens 1972, p. 8

- ^ Staff. "History and Traditions of The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards (Carabiniers and Greys)". British Army website. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011.

- ^ The Battle of Sheriffmuir Archived 26 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine at ScotsWar.com accessed 19 October 2009

- ^ a b John Percy Groves, History of the 2nd Dragoons – the Royal Scots Greys, "Second to none", 1678–1893, (Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston, 1893), p. 11.

- ^ "Battle of Dettingen". British Battles. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ "Battle of Fontenoy". British Battles. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Rodger 1993, p. 42.

- ^ Oliphant 2015, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Grant and Youens 1972, p. 11

- ^ Almack 1908, p. 41.

- ^ a b Almack 1908, p. 42.

- ^ The Battle of Minden at British Battle retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Frank McGlynn, 1759: The Year Britain Became Master of the World, (New York: Grove Press, 2004) pp. 277–279

- ^ a b c d e Grant and Youen 1972, p. 12

- ^ McGlynn 2004, pp. 281–283.

- ^ "Record of the Services of the 51st (Second West York) Or The King's Own Light Infantry", in the United Services Magazine, vol. 119, (London: Hearst and Blackett Publishers, 1869) pp.43–44.

- ^ Battle of Wilhelmsthal retrieved 25 October 2009 from BritishBattles.com

- ^ Almack 1908, p. 46.

- ^ Grant and Youens 1972, p. 13.

- ^ Almack 1908, p. 47.

- ^ Grant and Youens 1972, p. 14.

- ^ Almack 1908, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b Grant and Youens 1972, p. 15.

- ^ Almack 1908, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b c d Grant and Youens 1972, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Almack 1908, p. 49.

- ^ Grant and Youens 1972, p. 17.

- ^ a b Almack 1908, p. 51.

- ^ "Soldier's Story: James Hamilton, Rags to Riches". Waterloo 200. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ^ Grant and Youens 1972, p. 18.

- ^ David Hamilton-Williams, Waterloo, New Perspectives, The Great Battle Reappraised, (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1994), p. 269.

- ^ a b c Hamilton-Williams 1994, p. 299

- ^ Hamilton-Williams 1994, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Hamilton-Williams 1994, p. 300.

- ^ Patrick J. R. Mileham, The Scottish Regiments: A Pictorial History 1633–1987 (New York: Hippocrene Books, Inc., 1988) p. 8.

- ^ John Keegan, The Face of Battle (New York: Penguin Books, 1978) pp. 146–147.

- ^ The Battle of Waterloo and The Royal Scots Greys and Sergeant Charles Ewart retrieved on 25 October 2009.

- ^ a b Hamilton-Williams 1994, p. 301.

- ^ a b c d Grant and Youens 1972, p. 21.

- ^ Hamilton-Williams 1994, p. 302.

- ^ a b Hamilton-Williams 1994, p. 304.

- ^ Geoffrey Wooten, Waterloo, 1815: The Birth of Modern Europe (Osprey Campaign Series, vol. 15), (London: Reed International Books Ltd., 1993) p.42.

- ^ Hamilton-Williams 1994, p. 303–304.

- ^ Almack 1908, pp. 75–76.

- ^ John Sweetman, Balaclava 1854: The Charge of the Light Brigade (Osprey Campaign Series, vol. 6), (London: Reeds Books International, Ltd., 1995) p. 36

- ^ Ian Fletcher & Natalia Ishchenko, The Crimean War: A Clash of Empires, (Staplehurst: Spellmount Limited, 2004) p. 155.

- ^ Sweetman 1995, p. 41.

- ^ Fletcher and Ishchenko, p. 158.

- ^ Terry Brighton, Hell Riders: The Truth about the Charge of the Light Brigade, (London: Viking, 2004. Also New York: Henry Holt, 2005), p. 84.

- ^ Sweetman 1995, p. 52.

- ^ a b Sweetman 1995, p. 56.

- ^ a b Grant and Youens 1972, p.22

- ^ Sweetman 1995, pp. 56–57

- ^ a b Grant and Youens 1972, p. 23.

- ^ Sweetman 1995, p. 57.

- ^ a b Grant and Youens 1972, p. 24.

- ^ Sweetman 1995, pp. 58–61.

- ^ Fletcher and Ishchenko, p. 172.

- ^ a b Sweetman 1995, p. 65.

- ^ Adrian Mather, "How Lothian troops led the charge to glory at the Battle of Balaclava", Scotsman.com, 22 October 2004 retrieved on 25 October 2009.

- ^ a b Grant and Youens 1972, p. 25

- ^ Almack 1908, p. 83–84.

- ^ G F Bacon, "Early history of the Scots Greys", The Navy and Army Illustrated, The Glories and traditions of the British Army, 1897 at [1] Archived 17 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine retrieved on 25 October 2009.

- ^ Almack 1908, p. 85.

- ^ Byron Farwell, The Great Anglo-Boer War, (New York: Harper and Row Publishers, 1976) p. 55.

- ^ a b Anglo Boer War: 2nd (Royal Scots Greys) Dragoons Archived 13 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine retrieved on 25 October 2009.

- ^ John Stirling, Our regiments in South Africa, 1899–1902: their record, based on dispatches, (London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1903) p. 424.

- ^ a b c d e Anglo Boer War: 6th Dragoon Guards Archived 9 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine retrieved on 26 October 2009.

- ^ a b Farwell 1976, p. 292

- ^ Farwell 1976, pp. 292–293.

- ^ Farwell 1976, p. 293. Some have stated that de la Rey chose not to fight because he did not want to mow down unarmed prisoners of war. Others have said he retreated rather than risking an engagement against a force of unknown size.

- ^ Anglo Boer War: Lincoln Regt. Archived 19 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine retrieved on 27 October 2009.

- ^ Sir John Frederick Maurice, Maurice Harold Grant, History of the war in South Africa, 1899–1902, Volume 3 (London: Hurst and Blackett limited, 1908), pp. 238–239.

- ^ Battle of Zilikats Nek[permanent dead link] retrieved on 27 October 2009.

- ^ a b c Grant and Youens 1972, p. 28.

- ^ a b Michael Barthorp, The Old Contemptibles: the British Expeditionary Force, its creation and exploits, 1902–1914 (New York: Osprey Publishing, Ltd., 1989) p. 8.

- ^ 2nd Cavalry Division at 1914–1918.net retrieved on 30 October 2009.

- ^ a b c Grant and Youens 1972, p. 29

- ^ David Lomas and Ed Dovey, Mons 1914: the BEF's Tactical Triumph, Vol. 49 of the Campaign Series, (Osprey Publishing, 1997) p. 29.

- ^ Brigadier Sir James Edward Edmonds, Military Operations, France and Belgium, 1914–1918, Volume 1, (London: MacMillan and Co., Ltd., 1922) p. 215.

- ^ a b c d e Grant and Youens 1972, p. 30.

- ^ Richard A Rinaldi, Order of Battle British Army 1914, (Maryland: General Data, LLC, 2008) p.108.

- ^ "Poem". Scottish Newspapers.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grant and Youens 1972, p. 31.

- ^ The Arras Offensive April–June 1917 at 1914–1918.net retrieved on 30 October 2009.

- ^ The Cambrai Operations November–December 1917 at 1914–1918.net retrieved on 30 October 2009.

- ^ Battle of Amiens 1918 at 1914–1918.net 30 October 2009.

- ^ Alistair McCluskey and Peter Dennis, Amiens 1918: The Black Day of The German Army, (New York: Osprey Publishing, Ltd. 2008) p. 59.

- ^ a b c Grant and Youens 1972, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e f g Grant and Youens 1972, p. 33.

- ^ Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons) retrieved on 31 October 2009.

- ^ Gavin Long, Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army – Volume II: Greece, Crete and Syria, (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1953) pp. 397–400.

- ^ a b c Grant and Youens 1972, p. 34.

- ^ Michael Carver, El Alamein, (Ware: Wordsworth Editions Ltd., 1962) p. 59.

- ^ a b Royal Scots Greys 18/"List of units that served in the 4th Armoured Brigade". Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2007.