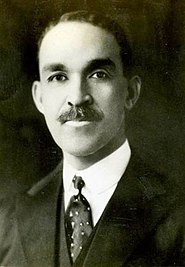

Benjamin Griffith Brawley

Benjamin Griffith Brawley (April 22, 1882 – February 1, 1939) was an American author and educator. Several of his books were considered standard college texts, including The Negro in Literature and Art in the United States (1918) and New Survey of English Literature (1925).[1]

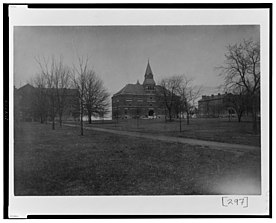

Born in 1882 in Columbia, South Carolina, Brawley was the second son of Edward McKnight Brawley and Margaret Dickerson Brawley.[2][3] He studied at Atlanta Baptist College (renamed Morehouse College), graduating in 1901, earned his second BA in 1906 from the University of Chicago,[1] and received his master's degree from Harvard University in 1908.[3] Brawley taught in the English departments at Atlanta Baptist College, Howard University, and Shaw University.

He served as the first dean of Morehouse College from 1912 to 1920 before returning to Howard University in 1937 where he served as chair of the English department.[3] He wrote a good deal of poetry, but is best known for his prose work including: History of Morehouse College (1917); The Negro Literature and Art (1918); A Short History of the American Negro (1919); A Short History of the English Drama (1921); A Social History of the American Negro (1921); A New Survey of English Literature (1925). In 1927, Brawley declined Second award and Bronze medal awarded to him by the William E. Harmon Foundation Award for Distinguished Achievement Among Negroes:[4] "... a well-known educator and writer, Brawley declined the second-place award because, he said, he had never done anything but first-class work."[5]

Biography

[edit]Education and early life

[edit]As a child, Benjamin Brawley learned that all men come from clay and that none of them should look up or down at each other, which kept him from approaching life with a pretentious attitude despite coming from a well-off family.[6] Brawley started developing a deep concern for people as a result of his interactions with children who were less privileged than he was, and his interest in people's life conditions is believed to have been consequential in his career as a teacher and a scholar.[6] Brawley's father was an educated man, and Brawley was one of nine children in the family.[7] Because of his father's position as a church minister, Brawley's family has had to relocate on many occasions in when he was a child.[8] Brawley's education started in his home where his mother served as his teacher until his family moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where he was admitted into third grade. During his time in Nashville, despite going to a normal school, Brawley's mother still read Bible stories and verses with him on Sundays.[8] As the son of a minister, Brawley studied Latin when he was twelve years old at Peabody Public School in Petersburg, Virginia, and he learned Greek when he was 14 years old with his father.[6] Brawley's father introduced him to the story of The Merchant of Venice, and he moved on to read stories, such as, Sanford and Merton and The pilgrim's Progress in addition to romantic stories that he read outside his family's library.[6]

In his adolescence, Brawley spent most of his summers earning from different jobs; he spent one summer working on a Connecticut tobacco farm, two summers at a printing office in Boston, and he spent some time as a driver for a white physician; besides his working summers, he spent the other half of his free time studying privately to get ahead at school.[6] Brawley entered the Atlanta Baptist Seminary (Morehouse College), where he became aware of the educational discrepancies in the community, at the age of thirteen -- most of his older classmates did not know much about classical literature or languages, such as Greek and Latin, which he knew plenty about.[8] During his time at Morehouse, Brawley not only excelled in his studies but he also assisted his classmates by revising their written assignments before they submitted them to their professors.[6] Besides his academic excellence, Brawley displayed significant leadership qualities; he managed Morehouse's baseball team; he served as quarterback for the football team and as a foreman for the College Printing Office.[8] Additionally, he and another student founded The Atheneum, a student journal that later became Maroon Tiger, in 1898, and this journal featured A Prayer, which Brawley wrote as a response to a lynching that happened in Georgia.[6]

Career and later years

[edit]Brawley graduated from The Atlanta Baptist Seminary with honors in 1901, and soon after, he launched his teaching career at Georgetown in a one-room school a few miles from Palatka, Florida where he cared for about fourteen children from first to eighth grade.[6][9] At that school, the term was limited to five months and his salary to no more than thirty dollars a month.[6] While Brawley received a more lucrative job offer right after signing with Georgetown, because he did not want to break a contract at the start of his career, he decided to honor his contract with Georgetown and turned down a contract that would allow him to work for longer school terms and that would significantly increase his monthly pay.[6] After the end of the school term and a year since he began his contract, Brawley headed to Atlanta for a teaching position at his former school, The Atlanta Baptist Seminary, where he continued to teach English for about eight years.[9] While teaching at The Atlanta Baptist Seminary, Brawley pursued a Bachelor of Arts degree and a Master of Arts degree, for which he completed most of the classes during summer sessions.[6] In 1806, he received his Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Chicago, and in 1808, he received his Master of Arts from Harvard University.[6]

In 1910, Brawley accepted an invitation to become a part of the faculty at Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he met a Jamaican lady from Kingston with the name Hilda Damaris Prowd who would later become his wife.[9] In response to their first meeting, Brawley wrote the sonnet First Sight. [6]Prowd and Brawley shared common interests in travels, operas, reading. and hosting friends.[6] Brawley and Prowd left Washington to move back to Atlanta, where Brawley was returning to teach English at The Atlanta Baptist Seminary (Morehouse College) and serve as the first dean of the institution.[6][9] During his first year there since returning, he taught six classes every day in addition to other teaching tasks.[6]

Brawley went to the Republic of Liberia in Africa to conduct an educational survey in 1920.[8] Sometime after his trip, Brawley decided to become a minister just like his father in early 1921.[8] Thus, he moved on to serve as a Baptist minister for The Messiah Congregation in Boston, Massachusetts.[8] A year later, he resigned from his position as a minister and returned to teaching because of incompatibility issues with the congregation's Christianity.[8] After quitting his ministerial position, Brawley went to teach at Shaw University in North Carolina, and a few years later, in 1931, he accepted a teaching position at Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he resided until his death in 1939.[8][10]

Publications and selected writings

[edit]- A Toast to Eggs For Breakfast" (poems), Atlanta Baptist College, 1902.

- The Problem, and Other Poems (poems), Atlanta Baptist College, 1905.

- A Short History of the American Negro, Macmillan, 1913; 4th revised edition, 1939.

- History of Morehouse College, Morehouse College (Atlanta, GA), 1917; reprinted, McGrath Publishing, 1970.

- Africa and the War, New York: Duffield and Company, 1918. [7]

- The Negro in Literature and Art in the United States, Duffield, 1918, revised edition, 1921; revised and retitled The Negro Genius: A New Appraisal of the Achievement of the American Negro in Literature and the Fine Arts, Dodd, 1937; reprinted, Biblo & Tannen, 1966.

- A Short History of the English Drama, Harcourt, 1921; reprinted, Books for Libraries, 1969.

- A Social History of the American Negro, Macmillan, 1921; reprinted AMS Press, 1971; reprinted Dover Publications, 2001. ISBN 0-486-41821-9.

- New Survey of English Literature: A Textbook for Colleges, Knopf, 1925, reprinted, 1930.

- Freshman Year English, New York: Noble and Noble, Publishers, 1929. [7]

- A History of the English Hymn, Abingdon, 1932.

- (Editor) Early Negro American Writers, University of North Carolina Press, 1935; reprinted, Books for Libraries, 1968.

- Paul Laurence Dunbar, Poet of His People, University of North Carolina Press, 1936, reprinted, Kennikat, 1967.

- Negro Builders and Heroes, University of North Carolina Press, 1937; reprinted, 1965.

- The Best stories of Paul Laurence Dunbar, New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1938. [7]

- The Seven Sleepers of Ephesys (poems), Foote & Davis (Atlanta, GA), 1971.[11]

- Three Negro Poets: Horton, Mrs. Harper, and Whitman. The Journal of Negro History 2.4 (1917): 384-392.

Newspapers and periodicals

[edit]- The Springfield Republican (Springfield) "American Drama and the Negro," II (1915), 9.[7]

- The Watchman-Examiner (New York) "Hymn as Literature," XIX (1930), 6.[7]

- The Athenaeum (Atlanta) "On Some Old Letters," XIV (1908), 6–8. "To the Men of Atlanta Baptist College," XIII (1910), 21–23. "George Sale and His Message to Atlanta Baptist College," XIV (1912), 48–50.

- The Bookman (New York) "The Negro in American Literature," LVI (1922), 137–141.

- The Champion of Fair Play (Chicago) "American Ideals and the Negro," IV (1916), 31–32.

- The Christian Register (Boston) "What The War Did to Krutown," X (1920), 33–35.

- The Crisis (New York) "Atlanta Striving," XXIIII (1914), 114–116.

- The Dial (Chicago) "The Negro in American Fiction," LX (1916), 445–450.

- The English Journal (Chicago) "The Negro in Contemporary Literature," XVIII (1929), 194–202.

- The Harvard Advocate (Cambridge) "Varied Outlooks," LXXXIV (1907), 67–69.

- The Home Mission College Review (Raleigh) "Is The Ancient Mariner Allegorical?" I (1927), 28–31. "Some Observations on High School English," II (1928), 36–42.

- Journal of Negro History (Washington, D. C.) "Lorenzo Dow," I (1916), 265–275. "Three Negro Poets: Horton, Mrs. Harper, and Whitman," II (1917), 384–392. "Elizabeth Barrett Browning and the Negro," III (1918), 22–25. "The Promise of Negro Literature," XIX (1934), 53–59.

- The Methodist Review (New York) "Wycliffe and the World War," IX (1920), 81–83. "Our Religious Re-Adjustment," XIII (1924), 28–30.

- The New South (Chattanooga) "Recent Literature on the Negro," XIII (1927), 37–41.

- The New Republic (New York) "Liberia One Hundred Years After," XXIV (1921), 319 321.

- The North American Review (New York) "Blake's Prophetic Writing," XXI (1926–1927), 90–94. "The Southern Tradition," CCXXIV (1928), 309–315.

- The North American Student (New York) "Recent Movements among the Negro People," III (1917), 8–11. (16) The Opportunity Magazine (New York) "The Writing of Essays," IV (1926), 284–287. "Edmund T. Jinkins," IV (1926), 383–385.

- The Reviewer (Chapel Hill) "A Southern Boyhood," V (1925), 1–8. "The Lower Rungs of the Ladder," V (1925), 78–86. "On Re-Reading Browning," V (1925), 60–63.

- Sewanee Review (Sewanee) "English Hymnody and Romanticism," XXIV (1916) 476 482. "Richard Le Gaillienne and the Tradition of Beauty," XXVI (1918), 47–60.

- The South Atlantic Quarterly (Durham) "Pre-Raphaelitism and Its Literary Relations," XV (1916), 68–81.

- The Southern Workman (Hampton) "Our Debts," XLIV (1915), 622–626. "The Negro Genius," XLIV (1915), 305–308. "The Course in English in the Secondary School," XLV (1916), 495–498. "A Great Missionary," XLI (1916), 675–677. "Meta Warrick Fuller," XLVII (1918), 25–32. "William Stanley Braithwaite," XLVII (1918), 269–272. "Significant Verse," XLVIII (1919), 31–32. "Liberia Today," XLIX (1920), 181–183. "The Outlook in Negro Education," XLIX (1920), 208–213. "Significant Days in Negro History," LII (1923), 86-9"A History of the high school," LIII (1924), 545-549. "On the Teaching of English," LIII (1924), 298–304. "Not in Textbooks," LIV (1925), 34–37. "The Teacher Faces the Student," LV (1926), 320–325. "Negro Literary Renaissance," LVI (1927), 177–184. "The Profession of the Teacher," LVII (1928), 481–486. "Dinner at Talfourd's," LVIII (1929), 10–14. "Citizen of the World," LIX (1930), 387–393. "The Dilemma for Educators," LIX (1930), 206–208. "Dunbar Thirty Years After," LIX (1930), 189–191. "Ironsides: The Bordentown School," LXI (1931), 410–416. "Plea for Tory," LX (1931), 297–301. "Art Is Not Enough," LXI (1932), 488–494. "Hamlet and the Negro," LXI (1932), 442–448. "Whom Living We Salute," LXI (1932), 401–403. "A Composer of Fourteen Operas," LXII (1933), 43–44. "Armstrong and the Eternal Verities," LXIII (1934), 80–87. "The Singing of Spirituals," LXIII (1934), 209–213.

- The Southwestern Christian Advocate (New Orleans) "Shakespeare's Place in the Literature of the World," XLV (1916), 3–11.

- The Springfield Republican (Springfield) "David Lloyd George," X (1923), 8.

- The Voice of the Negro (Atlanta) "Phillis Wheatley," II (1906), 55–59.

Poems in periodicals

[edit]- The Athenaeum (Atlanta) "At Home and Abroad," II (1899), 7. "Hiawatha," II (1899), 2. "Imperfection," II (1899), 4. "The Light of Life," II (1899), 5. "The Light of the World," II (1899), 5. Reprint in The Christian Advocate, (Chicago), XI (1920), 37. "Race Prejudice," II (1899), 9. "Bedtime," III (1900), 7. "Revocation," III (1900), 4. "Samuel Memba," III (1900), 2. "T. W.," Ill (1900), 8. "As I Gaze into the Night," IV (1901), 5. "The First of a Hundred Years," (Class Song), IV (1901), 6. "Poems," IV (1901), 7 and 9. "After the Rain," VI (1903), 7. "America," VI (1903), 2. "The Peon's Child," VII (1904), 6. "My Hero," XVII (1914), 7. Reprint in The Home Mission College Review, (Raleigh), I (1928), 30. "Shakespeare," XVIII (1916), 14. Reprint in The Home Mission College Review, (Raleigh), II (1928), 26.[7]

- The Christian Advocate (Chicago) "I Shall Go Forth in the Morning," XIII (1922), 18.

- Citizen (Los Angeles) "Ballade of One That Died Before His Time," IX (1915), 27.

- Crisis (New York) "The Freedom of the Free," XX (1913), 32.

- The Harvard Monthly (Cambridge) "Chaucer," XLV (1908), 184.

- Lippincott's Magazine (Philadelphia) "Crossroads," LXXIV (1905), 731.

- Survey (New York) "Battleground," XL (1918), 608.

- The Voice of the Negro (Atlanta) "Christopher Marlowe," I (1904), 65. "The Plan," I (1904), 524. "The Education," II (1905), 319. "First Sight," III (1906), 409. "To One Untrue," in (1906), 341. "Paul Laurence Dunbar," III (1906), 265.

Songs

[edit]- Song Collection Howard University Sings (edited), Washington, D. C., 1912. Pp. 10. Brawley wrote three of the eleven songs in the collection. [7]

- "Anniversary Hymn," Atlanta: Atlanta Baptist College Press, 1917. Written in response to the Fiftieth Anniversary of Morehouse College, Atlanta, Georgia. Set to music by Kemper Harreld. "Anniversary Hymn," Raleigh, 1929. Written on the occasion of the Sixty-Third Annual Founder's Day Celebration at Shaw University, Raleigh.

Edited works

[edit]- Early Negro American Writers, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1935. [7]

- New Era Declamations, Sewanee: The University Press of Sewanee, Tennessee, 1918.

- "The Baseball," Stories of the South, Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, 1931.

- "The Baseball," America Through the Short Story, Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1936.

- "The Negro in American Literature," The Bookman Anthology, New York: George H. Doran Company, 1923.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Roger M. Valade III, The Essential Black Literature Guide, Visible Ink, in association with the Schomburg Center, 1996; p. 53

- ^ "Benjamin Griffith Brawley (1882–1939)". www.historians.org. 2024-01-31.

- ^ a b c "Brawley, Benjamin Griffith (1882-1939)", at Blackpast.org

- ^ Parker, John W. (May 1934). Benjamin Brawley. The Crisis.

- ^ Calo, p. 115

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Parker, John W. (1955). "Benjamin Brawley and the American Cultural Tradition". Phylon. 16 (2): 183–194. doi:10.2307/272719. ISSN 0885-6818. JSTOR 272719.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Parker, John W. (1957). "A Bibliography of the Published Writings of Benjamin Griffith Brawley". The North Carolina Historical Review. 34 (2): 165–178. ISSN 0029-2494. JSTOR 23516848.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harlem Renaissance lives from the African American national biography. 2009-10-01.

- ^ a b c d "Benjamin Griffith Brawley | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- ^ "Brawley, Benjamin Griffith". South Carolina Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- ^ Benjamin Brawley Answers.com

Sources

[edit]- Calo, Mary Ann. (2007). Distinction and Denial: Race, Nation, and the Critical Construction of the African American Artist, 1920-40. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-03230-5 ISBN 978-0472032303

Further reading

[edit]- John W. Parker, "Phylon Profile XIX: Benjamin Brawley — Scholar and Teacher", Phylon (1940–1956), Vol. 10, No. 1 (1st Qtr. 1949).

External links

[edit]- Works by Benjamin Griffith Brawley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Benjamin Griffith Brawley at the Internet Archive

- Works by Benjamin Griffith Brawley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Benjamin Brawley Answers.com