German camps in occupied Poland during World War II

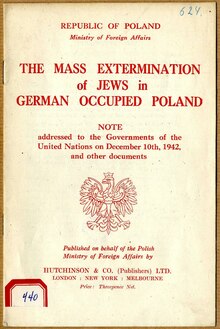

| Left to right (top to bottom): Concentration camp in Płaszów near Kraków, built by Nazi Germany in 1942 • Inmates of Birkenau returning to barracks, 1944 • Slave labour for the Generalplan Ost, making Lebensraum latifundia • Majdanek concentration camp (June 24, 1944) • Death gate at Stutthof concentration camp • Map of Nazi extermination camps in occupied Poland, marked with white skulls in black squares | |

| Operation | |

|---|---|

| Period | September 1939 – April 1945 |

| Location | Occupied Poland |

| Prisoners | |

| Total | 5 million Polish citizens (including Polish Jews and Gypsies)[1] and millions of other, mostly European, citizens |

The German camps in occupied Poland during World War II were built by the Nazis between 1939 and 1945 throughout the territory of the Polish Republic, both in the areas annexed in 1939, and in the General Government formed by Nazi Germany in the central part of the country (see map). After the 1941 German attack on the Soviet Union, a much greater system of camps was established, including the world's only industrial extermination camps constructed specifically to carry out the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question".

German-occupied Poland contained 457 camp complexes. Some of the major concentration and slave labour camps consisted of dozens of subsidiary camps scattered over a broad area. At the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, the number of subcamps was 97.[2] The Auschwitz camp complex (Auschwitz I, Auschwitz II-Birkenau, and Auschwitz III-Monowitz) had 48 satellite camps; their detailed descriptions are provided by the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.[3][4] Stutthof concentration camp had 40 subcamps officially and as many as 105 subcamps in operation,[5] some as far as Elbląg, Bydgoszcz and Toruń, at a distance of 200 kilometres (120 mi) from the main camp.[6][7] The camp system was one of the key instruments of terror, while at the same time providing necessary labour for the German war economy.

The camp system was one of the key instruments of terror, while at the same time providing necessary labour for the German war economy. Historians estimate that some 5 million Polish citizens (including Polish Jews) went through them.[1] Impartial scientific research into prisoner statistics became possible only after the collapse of the Soviet Empire in 1989, because in the preceding decades all inhabitants of the eastern half of the country annexed by the USSR in 1939 were described as citizens of the Soviet Union in the official communist statistics.[1]

Overview

Before the September 1939 Invasion of Poland, the concentration camps built in Nazi Germany held mainly German Jews and political enemies of the Nazi regime.[4] Everything changed dramatically with the onset of World War II. The Nazi concentration camps (Konzentrationslager, KL or KZ) set up across the entire German-occupied Europe were redesigned to exploit the labor of foreign captives and prisoners of war at high mortality rate for maximum profit. Millions of ordinary people were enslaved as part of the German war effort.[8] According to research by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,[9] Nazi Germany created some 42,500 camps and ghettos in which an estimated 15 to 20 million people were imprisoned. All types of confinement were used as a source of labour supply.[9]

Between 1941 and 1943, the concerted effort to destroy the European Jews entirely led to the creation of extermination camps by the SS for the sole purpose of mass murder in gas chambers. During the Holocaust, many transit camps as well as newly formed Jewish ghettos across German occupied Poland served as collection points for deportation under the guise of "resettlement". The unsuspecting victims used to mistakenly perceive their own deportations as work summons.[10] The Germans turned Auschwitz into a major death camp by expanding its extermination facilities. It was only after the majority of Jews from all Nazi ghettos were annihilated that the cement gas chambers and crematoria were blown up in a systematic attempt to hide the evidence of genocide. The cremation ovens working around the clock till November 25, 1944, were blown up at Auschwitz by the orders of SS chief Heinrich Himmler.[4][11]

Extermination camps

The vision of the Final Solution had crystallised in the minds of the Nazi leadership during a five-week period, from 18 September to 25 October 1941. It coincided with the German victories on the Eastern Front which yielded over 500,000 new POWs near Moscow.[12] During this time, the concept of Hitler's Lebensraum was redefined. Different methods of industrial-scale murder were tested and the sites of the extermination camps were selected.[13]

The new extermination policy was spelled out at the Wannsee Conference near Berlin in January 1942, leading to the attempt at "murdering every last Jew in the German grasp" thereafter.[13] In early 1942 the German Nazi government constructed killing facilities in the territory of occupied Poland for the secretive Operation Reinhard. The extermination camps (Vernichtungslager) were added to already functioning extermination through labor systems, including at Auschwitz Konzentrationslager and Majdanek; both operating in a dual capacity until the end of the war. In total, the Nazi German death factories (Vernichtungs- oder Todeslager) designed to systematically murder trainloads of people by gassing under the guise of a shower, included the following:

- German extermination camps in Poland

Vernichtungslager Nazi-delineated territory Polish location Holocaust victims 1 Auschwitz-Birkenau Oberschlesien Oświęcim near Kraków 1.1 million, around 90 percent Jewish.[14] 2 Treblinka * Generalgouvernement 80 km north-east of Warsaw 800,000–900,000 at Camp II (and 20,000 at Camp I).[15] 3 Belzec * Generalgouvernement Bełżec near Tomaszów Lubelski 600,000 with 246,922 from General Government.[16]

4 Sobibor * Generalgouvernement 85 km south of Brześć nad Bugiem 200,000 (140,000 from Lublin and 25,000 from Lwów).[17] 5 Chełmno Reichsgau Wartheland 50 km north of Łódź 200,000 (most via the Łódź Ghetto).[18] 6 Majdanek Generalgouvernement Lublin city district at present 130,000 per Majdanek State Museum research.[19] * Killing factories of secretive Operation Reinhard, 1942–43

The primary function of death camps was the murder of Jews from all countries occupied by Germany, except the Soviet Union (Soviet Jews were generally murdered by death squads). Non-Jewish Poles and other prisoners were also murdered in these camps; an estimated 75,000 non-Jewish Poles were murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Most extermination camps had regular concentration camps set up along with them including Auschwitz-Birkenau, Majdanek, and Treblinka I. However, these camps were distinct from the adjoining extermination camps.[20]

Concentration camps

At the beginning of the war, the new Stutthof concentration camp near Gdańsk served exclusively for the internment and extermination of the Polish elites. Before long, it became a nightmare of Moloch with 105 subcamps extending as far as 200 kilometres south into the heartland of Poland and more than 60,000 dead before the war's end, mainly non-Jewish Poles.[5] As far as forced labour, there was little difference between camp categories in Poland except for the level of punitive actions. Some camps were built so that the prisoners could be worked to death out of the public eye; this policy was called Vernichtung durch Arbeit (annihilation through work). Large numbers of non-Jewish Poles were held in these camps, as were various prisoners from other countries. Among the major concentration camps run by SS for the purpose of wilful killing of forced labourers, the most notable examples included the Soldau concentration camp in Działdowo, and the Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp made famous in the feature film Schindler's List and the Inheritance documentary.[21]

The Gross-Rosen concentration camp located in Rogoźnica, Poland (part of the German Silesia in World War II),[22] was surrounded by a network of 97 satellite camps (Aussenlager) populated with Polish nationals expelled from Nazi Wartheland in the process of ethnic cleansing. By October 1943, most inmates were Polish Jews including nearly 26,000 women.[23] There were similar camps, built locally, at Budzyń, Janowska, Poniatowa, Skarżysko-Kamienna (HASAG), Starachowice, Trawniki and Zasław servicing Nazi German startups which ballooned during this period.[2][24] War profiteers set up camps in the vicinity of the ghettos via Arbeitsamt, as in Siedlce, the Mińsk Ghetto (Krupp), and numerous other towns with virtually nothing to eat.[25]

War economy of Nazi Germany

Following the failure of the Blitzkrieg strategy on the Eastern Front, the year 1942 marked the turning point in the German "total war" economy. The use of slave labour increased massively. About 12 million people, most of whom were Eastern Europeans, were interned for the purpose of labour exploitation inside Nazi Germany.[26] Millions of camp inmates were used virtually for free by major German corporations such as Thyssen, Krupp, IG Farben, Bosch, Blaupunkt, Daimler-Benz, Demag, Henschel, Junkers, Messerschmitt, Philips, Siemens, and even Volkswagen,[27] not to mention the German subsidiaries of foreign firms, such as Fordwerke (Ford Motor Company) and Adam Opel AG (a subsidiary of General Motors) among others.[28] The foreign subsidiaries were seized and nationalized by the Nazis. Work conditions deteriorated rapidly. The German need for slave labour grew to the point that even the foreign children have been kidnapped in an operation called the Heuaktion in which 40,000 to 50,000 Polish children aged 10 to 14 were used as slave labour.[29] More than 2,500 German companies profited from slave labour during the Nazi era,[30] including Deutsche Bank.[31]

The prisoners were deported to camps servicing German state projects of Organization Schmelt,[23] and the war profiteering Nazi companies controlled by SS-WVHA and Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD) in charge of Arbeitseinsatz, such as Deutsche Wirtschaftsbetriebe (DWB), Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke (DAW),[32] and the massive Organisation Todt (OT),[33] which built Siegfried Line, Valentin submarine pens, and launch pads for the V-1 flying bomb and V-2 rocket,[34] among other slave labour projects such as the SS Ostindustrie GmbH, or private enterprises making German uniforms such as Többens and Schultz.[24]

Labour camp categories

The Germans pressed large numbers of Poles and Polish Jews into forced labour. The labourers, imprisoned in German Arbeitslager camps and subcamps across Poland and the Reich, worked for a broad range of war-related industries from armaments production and electronics to army uniforms and garments.[34] At most camps, including Buchenwald, the Poles and Polish Jews deported from Pomerania and Silesia were denied recognition as Polish nationals.[35] Their true numbers can never be known. Only 35,000 Poles who were still alive in 1945 came back to Poland and registered as Buchenwald survivors, others remained in the West.[35]

The Gross-Rosen population accounted for 11% of the total number of inmates in Nazi concentration camps by 1944,[36] and yet by 1945 nothing remained of it due to death march evacuation.[23] Auschwitz ran about 50 subcamps with 130,000-140,000 Poles on record, used as slave labour. Over half of them were murdered there; others were shipped to other complexes.[37] There were hundreds of Arbeitslager camps in operation, where at least 1.5 million Poles performed hard labour at any given time. Many of the subcamps were transient in nature, being opened and closed according to the labour needs of the occupier. There were also around 30 Polenlager camps among them, formally identified in Silesia as permanent (see list)[38] such as Gorzyce and Gorzyczki.[39] Many of the 400,000 Polish prisoners of war captured by Germans during the 1939 invasion of Poland were also imprisoned in these camps, although many of them were sent as forced labourers to the heartland of Germany. Several types of labor camps in this category were distinguished by German bureaucracy.[40]

- Arbeitslager was general-purpose term for labor camps in the direct sense.

- Gemeinschaftslager was a work camp for civilians.

- Arbeitserziehungslager were training labor camps, where the inmates were held for several weeks.

- Strafarbeitslager were punitive labor camps, originally created as such, as well as based on prisons.

- The term Zwangsarbeitslager is translated as forced labor camp.

- Polen Jugenverwahrlag were set up for Polish children hard to Germanize.

- Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle camps for the actual, and the presumed ethnic Germans.

Prisoner of war camps

The Germans established several camps for prisoners of war (POWs) from the western Allied countries in territory which before 1939 had been part of Poland. There was a major POW camp at Toruń (Thorn, called Stalag XX-A) and another at Łódź with hundreds of subsidiary Arbeitskommandos; Stalag VIII-B, Stalag XXI-D, plus a network of smaller ones including district camps. Many Soviet prisoners-of-war were also brought to occupied Poland, where most of them were murdered in slave labor camps. The POW camp in Grądy (Stalag 324) held 100,000 Soviet prisoners; 80,000 of them perished. The Germans did not recognise Soviets as POWs and several million of them died in German hands. They were fed only once a day, and the meal would consist of bread, margarine and soup.[41]

The victims

The Polish nation lost the largest portion of its pre-war population during World War II. Out of Poland's pre-war population of 34,849,000, about 6 million – constituting 17% of its total – perished during the German occupation. There were 240,000 military deaths, 3,000,000 Polish-Jewish Holocaust victims, and 2,760,000 civilian deaths (see World War II casualties backed with real research and citations).

The Polish government has issued a number of decrees, periodically updated, providing for the surviving Polish victims of wartime (and post-war) repression, and has produced lists of the various camps where Poles (defined both as citizens of Poland regardless of ethnicity, and persons of Polish ethnicity of other citizenship) were detained either by the Germans or by the Soviets.

Camps after the liberation

German camps were liberated by the Red Army and Polish Army in 1944 or 1945. A number of camps were subsequently used by the Soviets or Polish communist regime as POW or labor camps for Germans, Poles, Ukrainians, e.g.: Zgoda labour camp, Central Labour Camp Potulice, Łambinowice camp.[42]

Decrees of Polish Parliament

On 20 September 2001 the Sejm of the Republic of Poland introduced a special bill devoted to commemoration of Poland's citizens subjected to forced labour under German rule during World War II. The bill confirmed various categories of camp victims as defined during the founding of the Institute of National Remembrance (Dz.U.97.141.943),[43] but most importantly, named every Nazi German concentration camp and subcamp with Polish nationals in them. The list was compiled for legal purposes as reference for survivors seeking international recognition and/or compensation action. It included Soviet and Stalinist places of detention as well. Among the Nazi German camps were 23 main camps with Polish prisoners, including 49 subcamps of Auschwitz, 140 subcamps of Buchenwald, 94 subcamps of KZ Dachau, 83 subcamps of KZ Flossenbürg, 97 subcamps of Gross-Rosen, 54 subcamps of KZ Mauthausen, 55 subcamps of Natzweiler, 67 subcamps of KZ Neuengamme, 26 subcamps of Ravensbrück, 55 subcamps of KZ Sachsenhausen, 28 subcamps of Stutthof, 24 subcamps of Mittelbau and others. Without exception, they were set up by the Germans for the abuse and exploitation of foreign nationals.[22]

Naming of the camps by western media often cause controversies due to the usage of ambiguous phrase "Polish death camps" discouraged by the Polish and Israeli governments as loaded. All camps built in occupied Poland were German. They were set up during the reign of the Nazis over German-occupied Europe. Sporadically, the controversy is caused by the lack of sensitivity toward the history of the German occupation of Poland with comments made without awareness of the controversy.[44]

See also

- History of Poland (1939–45)

- The Holocaust in Poland

- Łapanka

- Potulice concentration camp

- Nazi crimes against ethnic Poles

- Operation Tannenberg

Notes

- ^ a b c Dr Waldemar Grabowski, IPN Centrala (31 August 2009). "Straty ludności cywilnej" [Polish civilian losses]. Straty ludzkie poniesione przez Polskę w latach 1939–1945. Bibula – pismo niezalezne. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

Według ustaleń Czesława Łuczaka, do wszelkiego rodzaju obozów odosobnienia deportowano ponad 5 mln obywateli polskich (łącznie z Żydami i Cyganami). Z liczby tej zginęło ponad 3 miliony. Translation: According to postwar research by Czesław Łuczak over 5 million Polish nationals (including Polish Jews and Roma) were deported to German camps, of whom over 3 million prisoners perished.

- ^ a b "Filie obozu Gross-Rosen" [Subcamps of Gross-Rosen, interactive]. Gross-Rosen Museum (Muzeum Gross Rosen w Rogoźnicy). Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ List of Subcamps of KL Auschwitz (Podobozy KL Auschwitz). Archived 2011-10-12 at the Wayback Machine The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Oświęcim, Poland (Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau w Oświęcimiu), 1999–2010 (in Polish)

- ^ a b c Compiled by Dr. Stuart D. Stein (2000), "German Crimes in Poland, Central Commission for Investigation of German Crimes in Poland. Volume I, Warsaw 1946", Background and Introduction, Howard Fertig, New York, 1982, archived from the original on 2011-06-22

- ^ a b Holocaust Encyclopedia (20 June 2014). "Stutthof". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ "Forgotten Camps: Stutthof". JewishGen. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Stutthof (Sztutowo): Full Listing of Camps, Poland". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

Source: "Atlas of the Holocaust" by Martin Gilbert (1982).

- ^ Ulrich Herbert (16 March 1999). "The Army of Millions of the Modern Slave State: Deported, used, forgotten: Who were the forced workers of the Third Reich, and what fate awaited them?". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ a b Anat Helman (2015). "The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos by Geoffrey P. Megargee". Exploring the Universe of Camps and Ghettos. Oxford University Press. pp. 251–252. ISBN 978-0-19-026542-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Getta tranzytowe w dystrykcie lubelskim (Transit ghettos in the Lublin district)". Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Pamięć Miejsca. Retrieved 20 May 2015. - ^ Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Oświęcim, Poland. 13 September 2005, Internet Archive.

- ^ David Glantz, Jonathan House, (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-1906033729, p. 343.

- ^ a b Browning (2004), p. 424.

- ^ Data sources: Rees, Laurence (2005). Auschwitz: A New History. New York: Public Affairs. ISBN 1-58648-303-X, p. 298. Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00239-9, p. 383.

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia, "Treblinka". Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. - ^ Jacek Małczyński (2009-01-19). "Drzewa "żywe pomniki" w Muzeum – Miejscu Pamięci w Bełżcu (Trees as living monuments at Bełżec)". Współczesna przeszłość, 125-140, Poznań 2009. University of Wrocław: 39–46. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Raul Hilberg (1985), The Destruction of the European Jews by Yale University Press, p. 1219. ISBN 978-0-300-09557-9.

- ^ MOZKC (28 December 2013). "Historia obozu (Camp history)" (Information for visitors). Chełmno extermination camp. Muzeum Kulmhof w Chełmnie nad Nerem. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Paweł Reszka (Dec 23, 2005). "Majdanek Victims Enumerated. Changes in the history textbooks?". Gazeta Wyborcza. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Archived from the original (Internet Archive) on November 6, 2011. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Moshe Lifshitz, "Zionism". (ציונות), p. 304; (in) Trapped in a Nightmare by Cecylia Ziobro Thibault, ISBN 1938908430.

- ^ "30th Annual News & Documentary Emmy Awards Winners Announced at New York City Gala" (PDF). National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original (PDF file, direct download 50.4 KB) on November 22, 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ a b Rozporządzenie Prezesa Rady Ministrów (29 September 2001). "W sprawie określenia miejsc odosobnienia, w których były osadzone osoby narodowości polskiej lub obywatele polscy innych narodowości". Dz. U. z dnia 29 września 2001 r. Dziennik Ustaw, 2001. Nr 106, poz. 1154. Archived from the original (Internet Archive) on February 13, 2006. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ a b c Dr Tomasz Andrzejewski, Dyrektor Muzeum Miejskiego w Nowej Soli (8 January 2010), 'Organizacja Schmelt.' Marsz śmierci z Neusalz (Internet Archive). Skradziona pamięć! Tygodnik Krąg. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Forced labor-camps in District Lublin: Budzyn, Trawniki, Poniatowa, Krasnik, Pulawy, Airstrip and Lipowa camps". Holocaust Encyclopedia: Lublin/Majdanek Concentration Camp. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ^ Edward Kopówka (translated from the Polish by Dobrochna Fire), The Jews in Siedlce 1850–1945. Chapter 2: The Extermination of Siedlce Jews. The Holocaust, pp. 137–167. Yizkor Book Project. Note: the testimonials from young children beyond their level of competence, such as G. Niewiadomski's (age 13) and similar others, quoted by the author from H. Grynberg (OCLC 805264789), are intentionally omitted for the sake of reliability. Retrieved via Internet Archive on 30 October 2015.

- ^ Marek, Michael (2005-10-27). "Final Compensation Pending for Former Nazi Forced Labourers". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2008-05-20. See also: "Forced Labour at Ford Werke AG during the Second World War". The Summer of Truth Website. Archived from the original on July 7, 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-20 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Marc Buggeln (2014). Slave Labor in Nazi Concentration Camps. OUP Oxford. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-19-101764-3 – via Google Books, preview.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Sohn-Rethel, Alfred Economy and Class Structure of German Fascism, CSE Books, 1978 ISBN 0-906336-01-5

- ^ Roman Hrabar (1960). Hitlerowski rabunek dzieci polskich : uprowadzanie i germanizowanie dzieci polskich w latach 1939–1945. Katowice: Śląsk. pp. 99, 146. OCLC 7154135 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jürgen Reents, ND (16 November 1999). "2,500 Firmen – Sklavenhalter im NS-Lagersystem" (in German). Die Zeitung "Neues Deutschland". Archived from the original on July 19, 2011 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Comprehensive List Of German Companies That Used Slave Or Forced Labour During World War II Released". American Jewish Committee. 7 December 1999. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008. See also: Roger Cohen (February 17, 1999). "German Companies Adopt Fund For Slave Labourers Under Nazis". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-20. "German Firms That Used Slave or Forced Labour During the Nazi Era". American Jewish Committee. January 27, 2000. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- ^ Erik Lørdahl (2000). German Concentration Camps 1933–1945. History. War and Philabooks. p. 59. ISBN 9788299558815. OCLC 47755822.

- ^ John Christopher (2014). Organisation Todt. Amberley Publishing. pp. 37, 150. ISBN 978-1-4456-3873-7.

- ^ a b Holocaust Encyclopedia (2014), The Gross-Rosen concentration camp (Internet Archive). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ a b Dr Bohdan Urbankowski (2010). "W cieniu Buchenwaldu (In the deep shadow of Buchenwald)". Pamięć za drutami. Magazine Tradycja, pismo społeczno-kulturalne. ISSN 1428-5363. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ "Historia KL Gross-Rosen". Internet Archive (in Polish). Muzeum Gross Rosen w Rogoźnicy. Archived from the original on April 23, 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Auschwitz Museum (2015). "Różne grupy więźniów. Polacy". KL Auschwitz. Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ FPNP database. "Lista Polenlagrów" (PDF 251 KB). Obozy przesiedleńcze i przejściowe na terenach wcielonych do III Rzeszy. Demart. p. 6. Retrieved May 14, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Das Bundesarchiv. "Directory of Places of Detention". Federal Archives. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

Search keyword: Polenlager

- ^ War relics (2013). "List of some of the more common terms and abbreviations". SS Dienstalterliste. Internet Archive. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Krzysztof Bielawski (11 January 2011). "Obóz jeniecki w Grądach k. Ostrowi Mazowieckiej" [Prisoner-of-war camp in Grądy]. Miejsca martyrologii – Zabytki. Ostrów Mazowiecka: Wirtualny Sztetl (Virtual Shtetl, POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews).

- ^ "One place, different memories". Geschichtswerkstatt Europa. 2010. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (24 January 1991). "Ustawa z dnia 24 stycznia 1991 r. o kombatantach oraz niektórych osobach będących ofiarami represji wojennych i okresu powojennego". Dz. U. z dnia 24 stycznia 1991 r. Dziennik Ustaw, 1997. Nr 142, poz. 950. Archived from the original (Internet Archive) on October 4, 2006. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Landler, Mark (30 May 2012). "Polish Premier Denounces Obama for Referring to a 'Polish Death Camp'". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

References

- Browning, Christopher R. (2004). The Origins of the Final Solution. Contributions by Jürgen Matthäus. London: William Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-01227-0.

- "Polish Council of Ministers decree on combatants and repressed". Archived from the original on October 4, 2006. Retrieved April 10, 2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Polish Council of Ministers "Decree on definition of detention sites". Archived from the original on February 13, 2006. Retrieved March 9, 2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - German Camps Polish Victims, The German occupation of Poland. Archived 2022-08-10 at the Wayback Machine Compendium of anti-Polish sentiment by PMI group; Cardiff, Wales.

- Hilberg, Raul (1985). The Destruction of the European Jews: The Revised and Definitive Edition. New York: Holmes and Meier. ISBN 0-8419-0832-X – via Internet Archive, Snippet view.

the final solution on a European-wide scale mobile killings.