Catholic Church in New Zealand

Catholic Church in New Zealand | |

|---|---|

| Hāhi Katorika ki Aotearoa | |

| |

| Classification | Catholic |

| Orientation | Latin |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Pope | Pope Francis |

| Archbishop | Paul Martin |

| Region | New Zealand |

| Language | English, Latin |

| Headquarters | Viard House, Sacred Heart Cathedral, Wellington |

| Origin | 1842 (vicariate)[1] |

| Number of followers | 470,919 (2018)[2] |

| Official website | catholic.org.nz |

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church by country |

|---|

|

|

|

The Catholic Church in New Zealand (Māori: Te Hāhi Katorika ki Aotearoa) is part of the worldwide Catholic Church under the leadership of the Pope in Rome, assisted by the Roman Curia, and with the New Zealand bishops.[3]

Catholicism was introduced to New Zealand in 1838 by missionaries from France, who converted Māori. As settlers from the British Isles arrived in New Zealand, many of them Irish Catholics, the Catholic Church became a settler church rather than a mission to Māori.[4]

According to the 2023 census, the largest single Christian religious affiliation in New Zealand, was "Christian (not further defined)" which recorded 364,644. "Roman Catholic" was second with 289,788.[5]

In New Zealand there is one archdiocese (Wellington) and five suffragan dioceses (Auckland, Christchurch, Dunedin, Hamilton and Palmerston North). The church is overseen by the New Zealand Catholic Bishops' Conference. Its primate is the Metropolitan Archbishop of Wellington, who has been Paul Martin since 2023.[6]

History

[edit]Beginnings

[edit]The first Christian service conducted in New Zealand waters may have occurred if Father Paul-Antoine Léonard de Villefeix, the Dominican chaplain of the French navigator, Jean-François de Surville, celebrated Mass in Doubtless Bay, near Whatuwhiwhi, on Christmas Day, 1769.[7][8]

Nearly 70 years later, in January 1838, another Frenchman, Bishop Jean Baptiste Pompallier (1807–1871) arrived in New Zealand as the Vicar Apostolic of Western Oceania. He made New Zealand the centre of his activities, which covered a vast area in the Pacific. He celebrated his first Mass in New Zealand at Totara Point, Hokianga, at the home of an Irish family, Thomas and Mary Poynton and their children, on 13 January 1838. Pompallier was accompanied by members of the Society of Mary (Marists), and more soon arrived. The mission headquarters were established in Kororāreka (later called Russell) where the Marists constructed a building (now called Pompallier) from pisé and set up a printing press. As well as stationing missionaries in the north, Pompallier began work in the Bay of Plenty, in the Waikato amongst Māori, and in Auckland and Wellington areas amongst European settlers.[9] In 1840, New Zealand became a British colony with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. The number of Catholic colonists comprised fewer than 500, from a total number of around 5000.

The Catholic Church established New Zealand as a separate vicariate in 1842.[10]

The mission splits

[edit]As a result of disagreement between Pompallier and Jean-Claude Colin, Superior of the Marists in France, Rome agreed to divide New Zealand into two ecclesiastical administrations from 1850. Pompallier became Bishop of Auckland and the Marist Bishop Philippe Viard (1809–1872) took charge of Wellington, which included the southern half of the North Island and the whole of the South Island. This decision meant that much of the Māori mission in the North (where most Māori lived) was abandoned; the Marists working in what became the Auckland diocese, including those who spoke Māori, moved to Wellington. However, Pompallier, who was in Europe in 1850, returned to New Zealand with more priests, the first Sisters of Mercy and ten seminarians, whose training was quickly completed. All but one of them were ordained within five weeks, and their training was the origin of St Mary's Seminary founded in that year.[11]

Increasingly, the Catholic Church in New Zealand was preoccupied with meeting the needs of the settler community. Many of the Catholic settlers were from Ireland, with some from England and Scotland. In the 19th century some were from English recusant gentry families, including Sir Charles Clifford, 1st Baronet (first Speaker of the New Zealand House of Representatives), Frederick Weld (sixth Premier of New Zealand) and their cousin William Vavasour.

The Wellington diocese was divided into three dioceses, with Dunedin (1869) and later Christchurch (1887) being established in the South Island.[12] In 1887, New Zealand became a separate ecclesiastical province. The hierarchy was established with Wellington becoming the archiepiscopal see. In 1900 Holy Cross College, Mosgiel, a national seminary for the training of priests, was opened. In 1907, when New Zealand was created a Dominion, there were 126,995 Catholics out of a total European settler population of 888,578.[10]

Māori

[edit]After 1850, the Māori mission continued in the Auckland diocese in an attenuated form and could not be revived until after the New Zealand Wars of the 1860s. The survival of the Māori church during the remaining decades of the 19th century was in large part due to Māori catechists – many of them trained at Pompallier's St Mary's Seminary.[13] James McDonald was the only missionary to the Māori in the late 1870s. In 1880, Archbishop Steins, the Bishop of Auckland, gave McDonald charge of the Māori mission.[14] In 1886, Bishop John Edmund Luck obtained Mill Hill Fathers for the mission. In spite of inadequate resources, the priests were very active. Some, like Father Carl Kreijmborg, were "builder-priests", themselves erecting churches. They also started credit unions, piggeries, dairy farms, and co-operative stores. Many of the priests were German or Dutch and they made lifelong commitments to their Māori communities. Some became more proficient in Māori than in English.

In the Wellington diocese the Marists continued their work, to a limited extent, amongst Māori, notably at Ōtaki. Mother Aubert (see below) contributed significantly in Hawke's Bay and later in Jerusalem. Catholic secondary schools for Māori were established: St Joseph's Māori Girls' College, Napier (1867) by the Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions; Hato Petera College, Northcote (1928) by the Mill Hill Fathers (later staffed by the Marist Brothers who had arrived in New Zealand in 1876); and, in 1948, Hato Paora College was opened by the Marist Fathers.[15] The first Māori Catholic priest, Father Wiremu Te Awhitu[16] was ordained in 1944, and the first Māori Catholic bishop, Bishop Max Mariu was ordained in 1988.[17]

Religious orders

[edit]Many Catholic religious orders came to New Zealand. The Sisters of Mercy arrived in Auckland in 1850 – the first order of religious sisters to come to New Zealand – and began work in health care and education.[18] The Congregation of Our Lady of the Missions arrived in Napier in 1867. When Patrick Moran arrived as the first Catholic Bishop of Dunedin in February 1871, he was accompanied by ten Dominican nuns from the Sion Hill Convent, Dublin, and they proceeded to establish their schools within days of unpacking.[19] In 1876, the same bishop obtained the services of the Christian Brothers who opened their Dunedin school in that year. In 1880, the Sisters of St Joseph of Nazareth came from Bathurst to Whanganui where they opened 7 schools between 1880 and 1900.[20] The Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart arrived in New Zealand in 1883 and established their first community at Temuka, South Canterbury.[21] During the next twenty years Mary MacKillop (St Mary of the Cross), the founder of that congregation, visited New Zealand four times to support her sisters.[22] Suzanne Aubert, who had come to New Zealand in 1860 at the invitation of Bishop Pompallier, and had worked in Auckland and Hawke's Bay, established her order the Sisters of Compassion in Jerusalem in 1892 and brought it to New Zealand in 1899.[23] In 1997 the New Zealand Bishops' Conference agreed to support the "Introduction of the Cause of Suzanne Aubert", to begin the process of consideration for her canonisation as a saint by the Church.[24] In the 20th century many other orders became established in New Zealand, including the Carmelite nuns in Christchurch and Auckland and the Cistercians in Hawke's Bay.

Development

[edit]

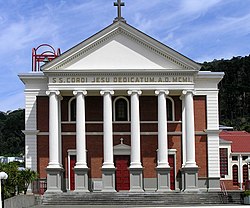

The prominence of churches in New Zealand's cities, towns and countryside attests to the historical importance of Catholicism in New Zealand.[25]

St Patrick's Cathedral is the cathedral of the Catholic Bishop of Auckland. It is on the original site granted by the Crown to Bishop Pompallier in 1841; it was renovated and re-opened in September 2007.[26] St Joseph's Cathedral, Dunedin, was constructed between 1878 and 1886. Sacred Heart Cathedral is the cathedral of the Archdiocese of Wellington and was opened in 1901 (in place of the destroyed St Mary's Cathedral), although it was not until 1984 that it became officially the cathedral.[27] The highly esteemed Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, Christchurch, was opened in 1905.[25] The latter three buildings were designed by the prominent New Zealand Catholic architect Francis Petre.[28] In 1947 another seminary, Holy Name Seminary, was opened in Christchurch. The cathedral of the Hamilton Diocese is the Cathedral of the Blessed Virgin Mary (built in 1975, rededicated in 1980 and renovated in 2008),[29] and the cathedral of the Palmerston North Diocese is the Cathedral of the Holy Spirit (built in 1925, renovated and rededicated in 1980).[30]

Church today

[edit]

Changing social attitudes in the 1950s and 60s and the sweeping changes ushered in by the Second Vatican Council affected the Catholic Church in New Zealand – including in areas of liturgy and church architecture. From 1970 Mass in New Zealand was said in either English or Māori.[31] The iconic Futuna Chapel was built as a Wellington retreat centre for the Marist order in 1961; the design by Māori architect John Scott fused Modernist and indigenous design principles and marked a deviation from traditional church architecture.[32]

On 6 March 1980, the Auckland Diocese and the Wellington Archdiocese were split to create the dioceses of Hamilton and Palmerston North respectively. There have been four New Zealand cardinals, of which all four held the position, successively, of Archbishop of Wellington and Metropolitan of New Zealand: Peter McKeefry, Reginald Delargey, Thomas Stafford Williams and current archbishop John Atcherley Dew.[33]

Pope John Paul II became the first pope to visit New Zealand, in November 1986. He was given an official state welcome, and presided at ceremonies attended by thousands.[34][35] He called for respect between cultures in New Zealand:

The Māori people have maintained their identity in this land. The peoples coming from Europe and more recently from Asia have not come to a desert. They have come to a land already marked by a rich and ancient heritage, and they are called to respect and foster that heritage as a unique and essential element of the identity of this country.[36]

In 2001, the Pope transmitted an apology for injustices done to the indigenous peoples of Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands, and asked for forgiveness where members of the church had been or still were party to such wrongs. The apostolic exhortation also condemned incidents of sexual abuse by clergy in Oceania.[37][38]

Sexual abuse cases

[edit]Of New Zealand Catholic diocesan clergy, 14% have been accused of improper behaviour (either fiscal, sexual abuse, psychological abuse or neglect) since 1950. There were 835 reported cases of alleged sexual child abuse since 1950.[39] From the 1990s, cases of abuse within the Catholic Church and other child care institutions began to be exposed in New Zealand. There were "at least three priests" convicted and several were criticised for allowing abuse to continue. The abuse was on a much lower scale than in Australia and many other countries because the Catholic Church had "a less prominent role in education and social welfare". In 2000 the Church acknowledged and apologised for the abuse of children by clergy, putting in place protocols and setting up a national office to handle abuse complaints.[40][41]

Demographics

[edit]In the 2013 census, 47.65 percent of the population identified themselves as Christians, while another 41.92 percent indicated that they had no religion and around 7 percent affiliated with other religions.[42] The main Christian denominations are: Catholics (12.61 percent); Anglicans (11.79 percent), Presbyterians (8.47 percent), and Christians not further defined (5.54 percent).[42] The 2013 census has shown an actual decline in Catholic adherents with a fall of some 16,000 members. However, the 2013 census also showed that the decline in the membership of the mainline non-Catholic denominations was greater, and that the Catholic Church had become the largest New Zealand Christian denomination, passing the Anglican Church for the first time in history.[2] The percentage of Catholics in the 1901 census was 14 percent, though at that time the church was only the third largest denomination.[43]

Regionally, the West Coast and Taranaki have the largest proportion of Catholics: 16.8 percent and 15.5 percent respectively at the 2013 census. Meanwhile, Tasman and Gisborne have the lowest proportion of Catholics at 7.4 percent and 8.2 percent respectively.[44]

Approximately 25 percent of New Zealand Catholics regularly attend Sunday Mass compared to 60 percent in the late 1960s.[45] In recent times numbers of priests, nuns and brothers have declined, and the involvement of laypeople has increased. There are 530 priests and 1,200 men and women religious.[citation needed] In 2024, there were 18 men training to be priests at Holy Cross Seminary.[46]

Social and political engagement

[edit]Catholic organisations in New Zealand are involved in community activities including education; health and care services; chaplaincy to prisons, rest homes, and hospitals; social justice and human rights advocacy.[47][48] Catholic charities active in New Zealand include the St Vincent de Paul Society[49] and Caritas Internationalis.[50]

Education

[edit]The first Catholic School in New Zealand was opened in 1840, the year the Treaty of Waitangi was signed, at Kororareka, and was called St Peter's School.[51] Initially Catholic missionaries, led by Bishop Pompallier, focused on schools for Māori. It was therefore Catholic laymen who in 1841 established a school for the sons of settlers. This school was Auckland's first school of any sort.[52][53][54] In 1877, the new central government passed a secular Education Act and the Catholic Church decided to establish its own network of schools. The system expanded rapidly. However, by the early 1970s, the Catholic system was on the brink of financial collapse trying to keep up with the post-WWII baby boom, suburban expansion, extension of compulsory education from six to nine years, and smaller class sizes. In 1975, the Third Labour Government passed the Private Schools Conditional Integration Act, which allowed the financially strapped Catholic school system to integrate into the state system. This means the school could receive government funding and keep its Catholic character in exchange for having the obligations of a state-run school, such as teaching the state curriculum. The land and buildings continue to be owned by the local bishop or a religious order and are not government-funded; instead parents pay "attendance dues" for their upkeep. Between 1979 and 1984, all but one Catholic school integrated into the state system.[55]

In June 2013, there were 190 Catholic primary schools in New Zealand and 50 secondary schools.[56] Around 86,000 students were enrolled in 2015, or just under 10 percent of all students in the New Zealand school system.[57][58] About 78 percent of New Zealand Catholic children attend Catholic schools.[58] Academically, the schools do very well. Between 1994 and 2010, the rolls in Catholic schools increased by almost 22 percent.[59] The New Zealand Catholic Education Office (NZCEO) assists in the running of Catholic schools in New Zealand.

Politics

[edit]In 1853 Charles Clifford and his cousin Frederick Weld were elected members of the 1st New Zealand Parliament. Both were from old English Catholic recusant families, and were educated at Stonyhurst College. Clifford was chosen as the first speaker of the House in 1854. Weld was a government minister from 1860, premier from 1864, and was later appointed governor of several British colonies (Western Australia, Tasmania, and the Straits Settlements). Henry William Petre was a member of the Legislative Council from 1853 to 1860; his father William Petre, 11th Baron Petre was chairman of the New Zealand Company, and also from the old recusant Petre family.[60]

In 1906 Liberal politician Joseph Ward, a Catholic, became prime minister. Ward was Australian-born and came from an Irish Catholic family. His political success was evidence that a Catholic could rise to the highest position in the land.[25] New Zealand Catholics were strongly represented in early Labour politics, which shared their dislike for the Protestant Political Association and supported Irish Home Rule.[31][25] In 1922, Bishop James Liston publicly rejoiced at Labour's electoral gains: "Thanks be to God, the Labour people, our friends, are coming into their own – a fair share in the Government of the country."[61] In 1935, New Zealanders elected a Labour government led by another Catholic prime minister, Michael Joseph Savage.[31] Later prime ministers Jim Bolger and Bill English were practising Catholics while serving in office.[62]

In the later 20th century, many Catholics took up justice and peace causes in their own communities, as well as nationally and internationally. New Zealand Catholics led protests against apartheid during the Springbok tour of 1981.[31]

Church leaders have often involved themselves in political issues in areas they consider relevant to Christian teachings. Recent political engagement by New Zealand bishops have included statements issued in relation to: the anti-nuclear movement;[63] Māori rights and Treaty of Waitangi settlements; the rights of refugees and migrants; and promoting restorative justice over retributive justice in New Zealand.[47]

In March 2013, Catholic bishops wrote to members of Parliament to state their strong objections to the Marriage (Definition of Marriage) Amendment Bill, which legalised same-sex marriage in New Zealand. The letter expressed concern that "state pressure will eventually be brought to bear against people’s freedom of conscience and speech."[64]

Dioceses and bishops

[edit]

There is one Roman Catholic archdiocese and five suffragan dioceses in New Zealand.[65]

| Diocese | Approximate regions | Cathedral | Creation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diocese of Auckland Bishop of Auckland |

Auckland, Northland | St Patrick's Cathedral | 1848 |

| Diocese of Christchurch Bishop of Christchurch |

Canterbury, West Coast | Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament | 1887 |

| Diocese of Dunedin Bishop of Dunedin |

Otago, Southland | St Joseph's Cathedral | 1869 |

| Diocese of Hamilton Bishop of Hamilton |

Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Gisborne | Cathedral of the Blessed Virgin Mary | 1980 |

| Diocese of Palmerston North Bishop of Palmerston North |

Manawatū-Whanganui, Taranaki, Hawke's Bay | Cathedral of the Holy Spirit | 1980 |

| Archdiocese of Wellington Archbishop of Wellington |

Wellington, Marlborough, Nelson, Tasman, part of West Coast | Sacred Heart Cathedral | 1848 |

New Zealand is also covered by three Eastern Catholic eparchies: the Melkite Eparchy of Saint Michael the Archangel (based in Sydney, Australia), the Chaldean Eparchy of Oceania (Sydney) and the Ukrainian Eparchy of Saints Peter and Paul (Melbourne, Australia).[65]

See also

[edit]- Military Ordinariate of New Zealand

- List of Catholic bishops in New Zealand

- List of saints from Oceania

- Christianity in New Zealand

- Catholic Church by country

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "History". The Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ a b 2018 Census totals by topic, Statistics New Zealand:: Tatauranga Aotearoa (1 Nov 2022)

- ^ "Home". New Zealand Catholic Bishops Conference. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ Sweetman, Rory (17 July 2018). "Catholic Church". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "Aotearoa Data Explorer". Stats NZ. 26 October 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "Archdiocese of Wellington – Archbishop". Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Wellington. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ So far, no record has been found to confirm that he did celebrate Mass on that day. 'Samuel Marsden's first service' (Ministry for Culture and Heritage). There is a record that he anointed (that is, gave the Sacrament of Anointing of the Sick) to several French sailors suffering from scurvy and its effects.

King, Michael (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand (ReadHowYouWant ed.). Accessible Publishing System PTY, Ltd (published 2011). pp. 120–121. ISBN 9781459623750.

After his chaplain, a Dominican Catholic named Paul-Antoine Léonard de Villefeix, had conducted the first Christian service in New Zealand waters on Christmas Day 1769, de Surville left the country [...].

- ^

Dunmore, John (30 October 2012). "Surville, Jean François Marie de". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

It is likely that the ship's chaplain, Father Paul-Antoine Léonard de Villefeix, celebrated Mass on Christmas Day, making this the first Christian service to be held in New Zealand.

- ^ Allan Davidson, Christianity in Aotearoa: A History of Church and Society in New Zeéaland, Third edition, Education for Ministry, Wellington, 2004, p. 16.

- ^ a b "Catholic Encyclopedia: New Zealand". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Michael King, God's Farthest Outpost: A History of Catholics in New Zealand, Penguin Books, Auckland, 1997, p. 73.

- ^ Davidson, p. 17.

- ^ Good Shepherd College website, Our History Archived 9 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine (retrieved 6 December 2011)

- ^ Simmons, E. R. "McDonald, James 1824 – 1890, McDonald, Walter 1830 – 1899". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ Davidson, pp 134–135.

- ^ Mariu, Max T. "Te Āwhitu, Wiremu Hākopa Toa". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Catholic Hierarchy website, Bishop Max Takuira Matthew Mariu SM

- ^ "Sisters of Mercy New Zealand". Sisters of Mercy New Zealand. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Michael King, God's Farthest Outpost: A History of Catholics in New Zealand, Penguin Books, Auckland, 1997, p. 95.

- ^ Diane Strevens, In Step with Time: A History of the Sisters of St Joseph of Nazareth, Wanganui, New Zealand, David Ling, Auckland, 2001, pp. 40 and 44.

- ^ Diane Strevens, MacKillop Women: The Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart Aotearoa New Zealand 1883–2006, David Ling, Auckland, 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Diane Strevens, MacKillop Women, p. 67

- ^ Michael King, God's Farthest Outpost, p. 107.

- ^ "Sisters of Compassion". Sisters of Compassion. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d Sweetman, Rory (17 July 2018). "Catholic Church – Building a national Catholic Church". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "St. Patrick's Catholic Cathedral Auckland". St Patrick's Catholic Cathedral Auckland. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Dan Kelly, On Golder's Hill: A History of Thorndon Parish, Sacred Heart Parish, Wellington, 2001, p. III.

- ^ Lochhead, Ian J. (1993). "Petre, Francis William". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ Dominic O'Sullivan & Cynthia Piper (eds) (2005). Standing Together: The Catholic Diocese of Hamilton 1840–2005. Wellington: Dunmore Press. p. 121.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "History". Cathedral of the Holy Spirit, Palmerston North. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d Sweetman, Rory (17 July 2018). "Catholic Church – Fitting into New Zealand society". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "Futuna Chapel". New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero. Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Archbishop John Dew named as new Kiwi cardinal". Stuff. 5 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "John Paul II – a memorial". New Zealand Catholic Bishops' Conference. Archived from the original on 1 May 2006. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Pope John Paul II makes lasting impression on New Zealand". Stuff. 18 November 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "Treaty of Waitangi". Caritas Aotearoa New Zealand. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Apostolic Exhortation Ecclesia in Oceania". Vatican Official Web Site. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Pope sends first e-mail apology". BBC News. 23 November 2001. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "New Zealand's Catholic church admits 14% of clergy have been accused of abuse since 1950". the Guardian. 1 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ Ben Heather, "Reports draw more church abuse complaints", The Dominion Post, 29 June 2013, p. A10.

- ^ "Catholic Church in NZ: Confronting Abuse". New Zealand Catholic Bishops' Conference. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ a b Table 28, 2013 Census Data – QuickStats About Culture and Identity – Tables.

- ^ "Census snapshot: cultural diversity". Statistics New Zealand. 6 March 2001. Archived from the original on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "2013 Census QuickStats about culture and identity – data tables". Statistics New Zealand. 15 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Karl du Fresne, "Holy Smoke" New Zealand Listener, 6 April 2013 p. 18.

- ^ https://www.holycross.org.nz/our-people

- ^ a b "Catholic Church in NZ: Living Justly". New Zealand Catholic Bishops' Conference. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Sisters of St Joseph – The Journey". Sisters of St Joseph Whanganui. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Welcome to the New Zealand Society of St Vincent De Paul Website". Society of St Vincent de Paul New Zealand. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Caritas Aotearoa New Zealand". Caritas Aotearoa New Zealand. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ Dinah Holman, Newmarket Lost and Found, 2nd edition, The Bush Press of New Zealand, Auckland, 2010, p. 247.

- ^ A. G Butchers, Young New Zealand, Coulls Somerville Wilkie Ltd, Dunedin, 1929, pp. 124 – 126.

- ^ "Auckland's First Catholic School – And its Latest", Zealandia, Thursday, 26 January 1939, p. 5

- ^ E.R. Simmons, In Cruce Salus, A History of the Diocese of Auckland 1848–1980, Catholic Publication Centre, Auckland 1982, pp. 53 and 54.

- ^ NZCEO Archived 24 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine; Rory Sweetman, 'A Fair and Just Solution': A history of the integration of private schools in New Zealand, Dunmore Press, Palmerston North, 2002, pp. 71–114.

- ^ "Number of schools by School Type & Affiliation – 1 July 2013". Ministry of Education. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Head of Catholic Education to step down". Voxy. 29 January 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ a b Orejana, Rowena (25 January 2015). "NZ Catholic". Brother Lynch knighted for educational work. Auckland. p. 2. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ "Catholic Schools – Today". New Zealand Catholic Education Office. 19 May 2010. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Family of Petre". Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent LLC. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Sweetman, Rory (1997). Bishop in the dock: the sedition trail of James Liston. Auckland: Auckland University Press. p. 262.

- ^ Karl, Du Fresne (25 July 2017). "New Zealand politics isn't as anti-Catholic as Britain's". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "Catholic Bishops Speak Out for Peace, Oppose Nuclear Weapons". New Zealand Catholic Bishops' Conference. 1982. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ Otto, Michael (11 March 2013). "Church leaders write open letter to MPs about marriage definition bill". NZ Catholic Newspaper. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Dioceses". The Catholic Church in Aotearoa New Zealand. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

References

[edit]- Allan Davidson, Christianity in Aotearoa: A History of Church and Society in New Zealand, Third edition, Education for Ministry, Wellington, 2004.

- Dan Kelly, On Golder's Hill: A History of Thorndon Parish, Sacred Heart Parish, Wellington, 2001.

- Michael King, God's Farthest Outpost: A History of Catholics in New Zealand, Penguin Books, Auckland, 1997.

- Michael King, The Penguin History of New Zealand, Penguin, Auckland, 2003.

- E.R. Simmons, A Brief History of the Catholic Church in New Zealand, Catholic Publication Centre, Auckland, 1978.

- Diane Strevens, In Step with Time: A History of the Sisters of St Joseph of Nazareth, Wanganui, New Zealand, David Ling, Auckland, 2001.

- Diane Strevens, MacKillop Women: The Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart Aotearoa New Zealand 1883–2006, David Ling, Auckland, 2008.

- Rory Sweetman, A Fair and Just Solution: A history of the integration of private schools in New Zealand, Dunmore Press, Palmerston North, 2002.

- Samuel Marsden's first service, Ministry for Culture and Heritage, updated 8 May 2014