Urban planning in Singapore

Urban planning in Singapore is the direction of infrastructure development in Singapore. It is done through a three-tiered planning framework, consisting of a long-term plan to plot out Singapore's development over at least 50 years, a Master Plan for the medium term, and short-term plans, the first two of which are prepared by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) and the last by multiple agencies.

Planning in Singapore first began with the Jackson Plan in 1822, which divided Singapore town into multiple ethnic areas and established Singapore as a commercial and administrative centre. For a century, the colonial authorities in Singapore were not very involved in its development until they began engaging in urban regulation in the 1890s, in response to congestion and squatter settlements. When this proved inadequate, the British established the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) in 1927, which had limited powers and hence limited initial impact. Detailed urban planning for Singapore eventually started in the 1950s, with the goal to give Singapore a wider economic role in the Federation of Malaya. The 1958 plan was produced as a result, heavily influenced by British planning practices and assumptions.

After Singapore's independence in 1965, planning policies were revised, and the State and City Planning Project was initiated to produce a new plan for Singapore, which became the 1971 Concept Plan. This plan laid out the basic infrastructure for Singapore's development and brought about the integrated planning process used ever since. Planning in Singapore began to incorporate additional priorities from the 1980s, such as quality of life and conservation, while the 1991 revision of the Concept Plan introduced the concept of regional centres to promote decentralisation. To improve the implementation of the Concept Plan's strategies, Singapore was divided into multiple planning areas in the 1990s, and comprehensive plans for each area's development were produced and compiled into a new plan. In the 2001 and 2011 concept plan, Singapore's urban planners began to incorporate public feedback and opinions into the planning process, shifting towards liveability and sustainability, while prioritising economic development as the powerhouse of each plan's success. The 2011 Concept Plan also featured a distinct focus on sustainability and conservation. The most recent plan is the 2019 masterplan, which details Singapore's increasing consideration towards sustainability, cultural preservation, building communities and closing resource loops.

History

[edit]Colonial Town Planning (1819 - 1958)

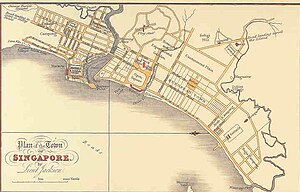

[edit]When Stamford Raffles, who founded Singapore in 1819, returned to the colony, he was dissatisfied with the haphazard development he encountered. At this time, Singapore was considered the trading factory and warehouse of the British East India Company. As a result, commercial houses and wharves grew disorderly along the banks of the Singapore River, a location known for its accessibility to trading boats.[1] A town committee was formed as a result, to ensure that Singapore developed and grew in an orderly manner, as part of Raffle's vision of Singapore as a commercial and administrative centre. The first official plan of the town, the Jackson Plan, was drawn up in December 1822 or January 1823.[2]

The strict regularity of the plan placed Singapore's streets and roads in a grid network. An area south of the Singapore River was set aside as a commercial and administrative centre, while the river's east bank, the 'Forbidden Hill' (Fort Canning Hill) and south-western tip was used for defence purposes.[2] Crucially, the plan divided Singapore into several ethnic subdivisions, the Europeans, Malays, Chinese, Indians, Arabs and Bugis were placed in separate ethnic enclaves.[3] To make Singapore a commercial and administrative centre, haphazardly constructed buildings were discouraged and significant disruptions were caused by the massive movements of people to and from their designated areas. Furthermore, to add professionalism to the planning process, Raffles secured the services of G.P Coleman, an architect and surveyor, and appointed Jackson, an assistant engineer), to build and oversee the development of the island.[4] It was Jackson who would have the most significant impact on the appearance of the town, building the earliest Raffles Institution and the earliest bridges across Singapore River.

The ethnic segregation was considered by some as part of a "divide and rule" strategy, a concerted effort by the British government to make residents reliant on them for matters related to race and ethnicity.[5] The demarcations also allowed the British political and economic control over the separated indigenous population, depending on the European Quarter as an administrative and commercial centre. This perspective is part of the larger critique of British hegemonic rule, where only selected ethnic leaders (mostly wealthy, professional and business Chinese) were represented in the Municipal Committee, which regulates ethnic interests. Such policies gave the appearance of mass support for British planning policies, such as those involving ethnic segregation, without considering the interests of the working class or other under-represented ethnic groups.[6]

The Jackson Plan formed the foundations of Singapore's Central Business District and morphologically, the grid street pattern provided the form for the central area. The rigidity of the street pattern also became one of the main reasons for traffic congestion post-war when private cars began to take to the streets. Long afterwards, the segregation of racial groups will continue to remain intact and only begin to change in the mid-1960s.[1]

For the next century, until 1958, there was little involvement by the colonial authorities in the planning of Singapore, and while the authorities occasionally modified Raffles' plan, they did not make any official plans on a comprehensive scale. The authorities only became more involved in urban development from the 1890s, taking responsibility for development work under the Municipal Bill of 1896, constructing back lanes and introducing building regulations. Nevertheless, these efforts were far from able to control urban development, and by the 20th century, Singapore faced congestion and squatter problems.[1] This observation was made with regards to Singapore in the 1920s:

... a striking example of a planless modern city and regional growth undirected by any comprehensive general plan and complementary schemes of improvement and development. The outcome of their modern growth is much unnecessary disorder, congestion and difficulties for which remedial measures have long been overdue [sic]

— Reade, Town Planning Adviser to the Federated Malay States (FMS)

In 1918, in response to a Housing Committee's findings regarding unsanitary living conditions posing a health hazard,[1] the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) was established in 1927. Tasked with carrying out urban improvement and rehousing works,[8] the SIT was not empowered to prepare comprehensive plans or to control development, initially only handling minor development schemes.[9] In the years preceding the Second World War, the SIT concentrated mostly on building and improving roads and open spaces, and constructing public housing.[1]

Post-World War II Town Planning (1958 and 1965 Master Plan)

[edit]During the British Military Administration after World War II, the British government was focused on alleviating the housing shortage in Singapore, redeveloping the central area and to improve living conditions in the congested city centre. At this time, Singapore faced an urgent need for environmental management and to control land use. This was further motivated by the vision that Singapore will play a wider economic role in the Federation of Malaya. A comprehensive plan for Singapore's development was drafted, but was not implemented after the return of civilian rule. Nevertheless, to provide more housing and raise living standards in the central area, the SIT started preparing a Master Plan in 1951. The plan was passed to the government in 1955 and was adopted in 1958.

In order to formulate the plan, the 1958 Master Plan undertook detailed surveys and forecasts of major variables: land use, population, traffic, employment and possible industrial development. A blueprint planning approach was adopted for the plan, with a strong emphasis on rational use of land for zoning and physical elements of the plan. The plan consisted of zoning throughout all urban land uses, open spaces such as greenbelts, and several new towns away from the city centre for the purpose of decentralization.[1] In addition, significant road network upgrades were proposed to handle predicted large increases in road traffic volumes, and two-thirds of slum residents were to be rehoused in formal housing. The plan was conceived with the expectation that Singapore would grow gradually and was unsuited for the social and economic change, rapid population growth and the Central Area's expansion in the early 1960s.[1] Expected to last for 20 years, the Master Plan was formulated to be an instrument of control which could be expanded or retracted. Several British planning assumptions were evident in the plan, such as the slow and steady rate of social change and minimal public sector intervention in planning, ideas transmitted through the involvement of British planners overseas.[1] Despite its short timeline, the 1958 Master Plan laid the groundwork for detailed urban planning in Singapore and came to be regarded as essential for the development of the country.

Singapore gained self governance in 1959 and was part of the Federation of Malaya for four years. The uneasy political arrangement and disputes over Singapore's status within the federation played a big influence on the planning process and the formulation of the 1965 Master Plan. While the 1958 Master Plan provided a guide for the control of development and land use, it became inadequate for the rapidly changing social and economic conditions in Singapore as a result of self governance and time lapses between policy formulation and implementation. The main problems that the plan had to target was the high rate of population growth, rapid expansion of central area, traffic congestion and deterioration of the city core.

Unlike the 1958 masterplan, the 1965 plan had a regional element, characteristic of the new government's priority that Singapore's future planning cannot be considered in isolation to its surrounding regions.[10] Beyond basic standard of living and amenity, the 1965 Plan re-oriented Singapore from a mere commercial outlet to a centre of manufacturing export for Malaysia's industries and a centre for industrial expansion. The population basis for planning was raised to between 3.5 and 4 million, and plans to accommodate this expanded population took the form of a radial expansion. The ''Ring City' would have urban centres along the coast and at selected inland sites. A network of highways and a Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) system will be used to provide transport. The First Review of the plan included an area encompassing southern Johore and Singapore Island, in line with the plan's regional focus. However, with Singapore's direction of development unclear, the 1965 Plan was held back innovatively and was not expected to last past 1972.

Post-independence and the Concept Plan (1965 - 1980s)

[edit]Singapore officially separated from Malaysia on 9 August 1965 and attained independence. As a new nation, the government had a new set of goals and priorities: national survival, achievement, and making Singapore a global city.[11] Survival was important to Singapore due to the communist confrontations experienced by the new administration in the early 1960s. Additionally, the rapid advance in information technology at the time made it essential for Singapore to become a global city. These goals, combined with the drive to attain excellence individually and organizationally as a new country, combine to produce the post-independence planning process.

Unlike the 1958 plan, post-independence planning was firmly set within the boundaries of main and offshore plans. The need for economic success was also urgently conveyed in the plans leading up to 1980s. To this end, planning began to become an institutionalized, professional act. Expertise was imported to prepare plans, specialist services were obtained in the fields of planning, and the State and City Planning (SCP) Department was created. Local professional staff were sent overseas to be trained. Post-independence planning was characterized by egalitarian goals and ensuring optimal land use. Land was considered a scarce resource, and allocation of land was seen as a communal or national act as opposed to an individual one. The SCP was focused on 'optimisation of the republic's land resources and resolving conflicting development proposals in the overall interest of the state for the common good'.[12]

The concept plan was developed in 1971, with the assistance of the United Nations Development Programme, which aimed to guide urban development in Singapore to the 1990s. The concept plan is based on the structure form of a 'Ring City', embodied by the ring-like structure of the transportation system.[11] It is a 'comprehensive' plan, aiming to include all feasible planning variables and options. Specific areas were marked out for residential, industrial and other uses. The central area, about 2 kilometres north and south of the Singapore River, was marked to be redeveloped. Unlike previous plans, the concept plan placed immense confidence in the ability of science and technology to alleviate planning problems, believing that the future could be sculpted and moulded through new innovations and efficient planning.[11] Through the cooperation of multiple agencies such as the Housing and Development Board (HDB), Planning Department, and the Public Works Department, the project released a draft plan in 1969, which, with several amendments, was approved in 1971 as the Concept Plan.

The plan was premised on the development of good infrastructure, which would facilitate economic growth, satisfy housing requirements and basic social needs of the population. Key infrastructure developments included the new international Changi Airport, a mass rapid transit system, and a new expressway system. High density housing would be concentrated along high capacity transportation routes, while the central area would be cleared of its residential population, in an effort to decentralise.[11] Meanwhile, the city core would be redeveloped as an international financial, commercial, and tourist centre. Key developments in the city core include Shenton Way (Singapore's Wall Street) and Orchard Road (a shopping belt for tourists and higher-income Singaporeans). Other areas outside of the city core like Tampines New Town were transformed from rural wastelands to modern residential living areas, whereas Jurong Industrial Estate was developed into a thriving industrial and residential area. Industrial estates were also located at Sembawang, Yishun and Tanjong Rhu, forming one of the main engines for Singapore's growth. Singapore's highly efficient transportation system, the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT), is also a product of the 1971 Concept Plan, speaking to its success in moulding Singapore today.

Key agencies tasked to execute the plan were the State City Planning Department (SCPD), Housing Development Board (HDB), Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), Jurong Town Corporation (JTC) and the Public Works Department (PWD). In particular, the HDB suburbanized the population, providing quality accommodation as good as private housing, to more than four-fifths of the population.[13] URA also played a key role in rejuvenating the old core of the city, demolishing 1500 acres of the old city core to build a new one. Through 'active programs' which involved both public and private participation, URA revamped the road system and drastically changed the built environment of central Singapore.[11] Led by its three guiding principles of conservation, rehabilitation, and rebuilding, URA planned and created a city that is physically, economically, and culturally regarded as a modern metropolis.

At the foundation of the plan was the Compulsory Land Acquisition Act, introduced in 1966, which allowed the government to acquire, amalgamate, and redevelop land. The act allowed for unobstructed clearance of land for development.[14] The simultaneous development of mass housing and urban renewal also allowed large amounts of the population to be systematically transferred from the city core to the suburbs. Since housing and urban renewal were at the top of the government's priorities, URA was given access to resources, capital, and manpower on a national scale for its development activities.[14]

The 1971 Concept Plan marked a change in the nature of Singapore's urban planning from one based on the possible directions Singapore's development could take to one based on the path its development should take, and the introduction of an integrated planning process brought about by inter-agency cooperation. Moreover, it laid out the basic infrastructure from which Singapore developed further.

The 1980s and 1990s

[edit]While Singapore's development focused mainly on economic success during the initial post-independence years, as Singaporeans became more affluent in the 1980s, planners started taking into account quality of life factors. Additional land within new towns was allocated for parks and open spaces, while gardens and common facilities were incorporated into public housing estates to foster a sense of community between residents. Moreover, from 1980, industrial planning shifted towards infrastructure and areas suited for higher value industries, and industrial areas started to be constructed as "business parks". These "business parks" had cleaner environments than earlier industrial areas.

A review of planning of the Central Area culminated in the Structure Plan in 1984. Under this plan, several districts in the city centre were identified for conservation, open spaces and parks were clearly marked out, and other districts, such as the Golden Shoe and Orchard Road districts, were designated as areas for high-density development. More attention was also paid to conservation, with the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) setting aside certain parts of the city centre for conservation in 1986, and announcing the Conservation Master Plan in 1989, under which entire areas in the city centre could be conserved.

As the 1971 Concept Plan's plan period ended in 1992, a revised Concept Plan was released in 1991. In line with the shift towards making Singapore more liveable, the revised Concept Plan touched on all aspects of life, from business to leisure, powered by economic growth. Its main focuses include sustaining economic growth, increasing transport efficiency and providing comfortable accommodation for 4 million people and improving the quality of life for the population. Economic growth will be sustained through providing land to meet the needs of all industries, developing business parks, constructing four regional centres (Tampines, Seletar, Woodlands, Jurong East) and transforming the Marina Bay area into an international business hub.[11] The plan for four regional centres is consistent with the policy of decentralisation that began in the 1970s. There will be a distinct identity and economic focus for each regional centre, which will be self-contained. Each regional centre would serve as a regional hub employment, shopping, business, entertainment and cultural activities. With the objective of economic decentralisation, companies were also encouraged to spread out to the regional centres. The plan also detailed that the transport system will be improved by focusing on areas of maximum accessibility and by expanding the transport network. New MRT stations, a new ferry system, light rail, cycleways and walkways were also planned to reduce automobiles on the road.[11]

The revised Concept Plan also prioritised the need for Singapore to move away from manufacturing-oriented industries to professional and higher technology industries. Business parks were planned to be built along technology corridors, in close proximity to major transportation nodes and regional centres. These parks are geared towards image-conscious, knowledge based companies, with heavy landscaping and high quality working environments to attract companies which are higher in the value chain.[11] To complement these business parks, the Marina Bay area will also become a downtown core area, with new hotels, shopping facilities, entertainment, convention centres and a new waterfront promenade. However, Singapore did not give up on their industrial planning entirely. In order to ensure that they stay competitive in the global market, Singapore shifted towards the development of industrial clusters in the 1990s. These clusters were industrial areas in which multiple businesses in the same industry were consolidated, in order to foster mutual support between companies and increase economies of scale. Furthermore, to ensure optimal land use, minimum plot ratios were introduced and older industrial areas were redeveloped for more productive industries. Land reclamation was also carried out to increase the land available for industrial use.

While Singapore pivots towards becoming an Asian economic powerhouse, the revised plan did not forget the importance of creating a beautiful city in facilitating this change. Urban development would be integrated with the natural environment, with an island-wide network of blue and green linkages and locating residential estates near waterfronts, parks and gardens. Development of more resorts, marinas, beaches, sports facilities, entertainment complexes and theme parks were also planned to provide the population a wider range of leisure options.[15] Historic areas in the city were also strategically conserved to be developed into a 'Civic District' in order to attract tourists and maintain Asian roots in the city.

To aid the implementation of the Concept Plan's aims, Singapore was divided into 55 planning areas. Development Guide Plans, comprehensive plans for each planning area, were drawn up between 1993 and 1998, and the resulting plans were compiled into a plan for the whole island.

2000s to present

[edit]Public consultation and feedback started playing a greater role in Singapore's urban planning from the early 2000s, and for the preparation of the 2001 Concept Plan, focus groups were formed to discuss urban planning issues. The 2001 plan mainly focused on quality of life, proposing more diverse residential and recreational developments, and balancing the goals of liveability and economic growth. This included plans to build housing in mature estates, in the new downtown at Marina South and at the western area of the island.[16] Green spaces would be expanded from 2000 to 4500 ha, with the opening of areas such as Pulau Ubin and the Central Catchment Reserve, which will be accessible by Park Connectors.[16] Sport facilities will also be built for recreational purposes, complementing the opening of reservoirs, where residents can exercise and enjoy closer access to nature.

Much like the 1991 Concept Plan, the 2001 concept plan prioritized the shift towards higher-value industries, such as electronics and pharmaceuticals. It included the proposal of a new zoning system to differentiate business and industrial uses based on their impact to the environment.[16] A new white zone was also introduced, designated for multiple industries, and were referred to by the government as "mixed-use developments". These areas consisted of plots that could be used in multiple ways, with multiple open spaces between developments, and were intended to foster the development of knowledge-based and creative industries in Singapore. Three regional centres were also added to the mix, with Tampines, Jurong East and Woodlands supported by an expansive train network which provides links to places island-wide. Furthermore, in response to population changes in the 2000s, the Land Transport Authority (LTA) released the Land Transport Master Plan 2008, which called for bus route planning to be handled by the LTA, a significant expansion of the rail network, and for the integration of the bus and rail systems in a hub-and-spoke network. The subsequent Master Plan, released in 2013, called for more sheltered walkways and cycling path networks within new towns to improve pedestrian and cycling access.

In response to recommendations by focus groups during the 2001 Concept Plan review to form a conservation trust to foster more public engagement, a Conservation Advisory Panel was formed in 2002. Consisting of members from many parts of society, it was intended to provide feedback on the URA's conservation proposals, and to encourage the public to learn more about Singapore's built heritage. In addition, Identity Plans were introduced in the same year for fifteen districts across Singapore. For these plans, studies of the districts were made, and public feedback and forums were handled by Subject Groups formed for each district. This was part of a larger effort to enrich Singapore's heritage, culture and diversity and to enhance Singapore's natural environment. By retaining cultural and historic landmarks and integrating them with the new developments, this can create a sense of continuity and history in the new towns. New towns will also be smaller and carry a unique sense of identity, to create a sense of ownership for residents.[16]

In 2011, the Concept Plan was revised yet again, with a focus on sustainability. A focus group on 'Sustainability and Identity' was assembled to discuss three key issues: Quality of Life, Sustainability, Ageing and Identity. Based on the feedback from this focus group, which emphasized strengthening green infrastructure, empowering green practices, and making Singapore an endearing home, the Concept Plan was formed.[17] Green infrastructure would consist of green buildings which conserve energy and have better life cycles, green mobility such as cycling, walking infrastructure and green habits, which consist of making recycling and reducing waste part of Singaporean's daily consciousness. Efforts to make Singapore an endearing home include preserving heritage buildings, introducing more live-in population to heritage districts, adding sculptures and public art to parks and housing estates and fostering partnership between community members such as business-owners and residents.[17]

Industrial areas in the 2010s were planned to be further integrated, with districts comprising residential, recreational and industrial developments closely linked together. In addition, building conservation saw the greater involvement of the public and the National Heritage Board, through the establishment of a Heritage Advisory Panel and the Our Heritage SG Plan for the heritage sector, while the Conservation Advisory Panel was replaced by a Heritage and Advisory Partnership in 2018. This partnership, besides providing feedback for conservation proposals, was intended to generate new proposals regarding building heritage in Singapore.

Current planning policy

[edit]

Singapore's planning framework comprises three tiers, a long-term plan, the Master Plan, and detailed plans.[18] The long-term plan, formerly called the Concept Plan,[19] plots out Singapore's developmental direction over at least five decades. Intended to ensure optimal land use to meet economic growth targets and handle expected population increases, it is revised every 10 years. The Master Plan, intended for the medium term, comprises land use plans across Singapore, and is revised every five years, while the detailed plans, issued by agencies supervising certain aspects of urban development, plot out short-term development. Preparation of the long-term plan and Master Plan is done by the URA,[18] while the URA carries out the planning process in cooperation with four other agencies, namely the LTA, the HDB, Jurong Town Corporation, and the National Parks Board.[20]

Under Singapore's current planning policy, development outside the central area comprises independent new towns, with residential, commercial and industrial areas, linked by expressways and a rail network. These new towns are in turn served by four regional centres, one in each region of Singapore, which carry out some of the functions of the central area.[18] Moreover, the new towns are planned out with the intent to foster community interaction, improve connectivity, and to improve quality of life, with common areas, integrated cycling and pedestrian path networks, and widespread greenery.[21]

Transport planning in Singapore consists of the Land Transport Master Plan, which is revised every five years, and development plans for the rail and bus system. Built upon a spoke-hub distribution paradigm, Singapore's transport planning has several key aims, namely increased connectivity, improved public transport provision, and increasing the proportion of commuters using public transport.[20]

The 2019 Master Plan

[edit]The current Master Plan, released in 2019, focuses on the themes of liveable and inclusive communities, sustainability, sustainable mobility, conservation of historic areas and Singapore as an international gateway.[22] In order to create closer knit communities, new towns will be well-connected and amenities will be community-centric so that public spaces can become more vibrant and inclusive.[23] The plan details working with communities and protecting built heritage, in order to create distinct and unique local identities, creating place character and continuity.[24] Continuing their shift towards sustainable mobility in the 2001 Concept plan, mobility will be encouraged with better connectivity across Singapore by enhancing cycling and pedestrian networks, promoting public transport use, making business nodes closer to homes and more easily accessible, and increasing the efficacy of goods delivery.[25] This includes four additional new rail lines, the Cross Island Line, Jurong Regional Line and Thomson East-Coast Line, which will be complemented by Integrated Transport Hubs which place rail and bus services in close proximity to MRT stations.[26] A new Connectivity Special Detailed and Control Plan was also developed such that cycling and pedestrian paths can be designed to provide optimised connectivity and bike parking will also be integrated within the new developments. A Transit Priority Corridor is also in the works, where bus lanes and cyclists enjoy seamless journeys, encouraging residents to cycle or take public transport.[26]

Like the plans before, the 2019 Master Plan also has a big focus on economic development in various distinct economic zones. The Northern area has been primed for growth industries and innovative sectors, with key developments such as Agri-Food Innovation Park at Sungei Kadut and the Punggol Digital District complementing the current Woodlands Regional Centre.[27] The central area, home to Singapore's financial hub, will continue to grow, accommodating more nearby housing and a larger diversity of jobs in the future. The Eastern Gateway, bolstered by the recent opening of Jewel Changi Airport and the expansion of Changi Air Hub, will continue to be a gateway for Singapore to the rest of the world. An additional Changi East Urban District will join the current lifestyle-business clusters in the area, bringing more jobs to the East.[27] Lastly, the Western Gateway will be anchored by the new Jurong Lake District (JLD), planned as the largest commercial node outside of the Central Business District, which is bolstered by its close proximity to world-class universities, the National University of Singapore and Nanyang Technological University.

The 2019 Masterplan also reflected Singapore's worries about climate change and recent commitment to cut greenhouse gas emissions to half by 2050, with a strong emphasis on protecting Singapore against climate conditions and creating sustainable communities. This includes efforts to protect the coastline with flood walls and revetments, raising minimum platform levels, widening and deepening drains in order to mitigate increasing flood risk as a result of climate change and rising sea-levels.[28] Other efforts to close resource loops and reduce energy use include strengthening current national water supply, exploring the use solar panels at Tengah Reservoir, building super-low energy buildings such as ALICE@Mediapolis and aiming for zero waste, with a recycling rate of up to 70%.[29] The Masterplan also explores the use of underground space and co-location for pedestrian linkages, car parking and the expansion of the public transport network, in order to preserve space in land-scarce Singapore.[30]

Singapore sees a distinct shift towards sustainability and addressing climate-change related fears in its recent planning policies. Beyond being an economic powerhouse, Singapore's planning priorities have expanded to sustainability, culture and resource preservation, bolstered by the use of advanced technology to create smarter cities.

Criticism

[edit]Singapore has been referred to by many as the "best-planned city" in the world, with planners lauding the rapid development from British colony to global city, world-class public infrastructure, efficient public transportation and wide-scale affordable housing.[31] Over 90% of Singaporeans or Permanent Residents own their own home and at the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale, it was calculated that with Singapore's land-use efficiency, the world's population could fit into 0.5% of the Earth's landmass.[31] Common traits cited for Singapore's successful urban planning include clean streets, automobile restrictions, ubiquitous greenery and distinct lack of urban sprawl.[32]

However, Singapore's highly curated, meticulously planned city is also not without its critics. Some have criticised Singapore's lack of spontaneous organic city growth and that the emphasis on a highly controlled urban plan has resulted in a sterile city.[31] Others have also criticised the façade of high public-housing ownership, when in reality, due to the Land Acquisition Act which allows the government to own most of Singapore's underlying land, 80% of HDB residents only have 99-year leases on their flats, which depreciates in value as the 99-year term approaches.[32] In the same vein, other planning outcomes such as low-car ownership were also a result of controversial policies. Car-owners have to obtain a 'Certificate of Entitlement' in order to own a car, which typically costs SGD$70,000 to SGD$100,000 (US$50,000 to US$75,000), which critics say makes cars unaffordable for lower-income families. Moreover, with an almost eagle-like focus on economic development in its early days, critics lament the loss of historical buildings for economic development, though conservation efforts have been increased in recent planning efforts. Much of the criticism stems from dissatisfaction against what critics regard as Singapore's semi-authoritarian political system and the impingement on personal freedoms as a result of planning policies.

Sustainability advocates have also been urging for even more sustainable planning policies, arguing that Singapore's commitment to slash carbon emissions by half by 2050 does not fulfil the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) requirements.[33] Believing that Singapore should slash carbon emissions to zero by 2050, advocates argue against the unsustainable use of Pulau Semakau Island for waste incineration and disposal, citing that landfill space will run out by 2035, the use of petroleum and natural gas as a source of energy and the petrochemical industries located on Jurong Island. Many also criticise Singapore's heavy focus in flood and climate change protection in the masterplan, declaring that more attention should be given to Singapore's unsustainable economic and energy sources.

In February 2021, a woodland reserve the size of 10 football fields just Northwest of Kranji was accidentally cleared for construction purposes, drawing intense criticism from Singapore's conservation groups. They argued that the forest was an important ecosystem, green corridor and one of the few remaining forests in Singapore, using this incident to highlight their view that planning in Singapore should do more to protect and preserve existing forests and wildlife.[34]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Teo, Siew Eng (April 1992). "Planning Principles in Pre- and Post-Independence Singapore". The Town Planning Review. 63 (2): 163–185. doi:10.3828/tpr.63.2.vr76822vu248631x. ISSN 0041-0020. JSTOR 40113142.

- ^ a b Pearson, H. F. Singapore from the sea, June 1823 : notes on a recently discovered sketch attributed to Lt. Philip Jackson. OCLC 1000472729.

- ^ "Jackson Plan". www.roots.gov.sg. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Hancock, T. H. H. (1986). Coleman's Singapore. Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society in association with Pelanduk Publications. OCLC 15808897.

- ^ "Multiracial Singapore: Ensuring inclusivity and integration". lkyspp.nus.edu.sg. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ Subramaniam, Aiyer (2007). From colonial segregation to postcolonial 'integration' - constructing ethnic difference through Singapore's Little India and the Singapore 'Indian'. University of Canterbury. School of Culture, Literature and Society. OCLC 729683976.

- ^ Home, R. "Colonial Town Planning in Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong". Planning History. 11 (1): 8–11.

- ^ Yuen, Belinda (2011). "Centenary paper: Urban planning in Southeast Asia: perspective from Singapore". The Town Planning Review. 82 (2): 145–167. doi:10.3828/tpr.2011.12. JSTOR 27975989. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Jensen, Rolf (July 1967). "Planning, Urban Renewal, and Housing in Singapore". The Town Planning Review. 38 (2): 115–131. doi:10.3828/tpr.38.2.eg304r3377568262. JSTOR 40102546. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Master plan first review, 1965 : report of survey. Singapore: Planning Department. OCLC 63345870.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eng, Teo Siew (April 1992). "Planning principles in pre- and post-independence Singapore". Town Planning Review. 63 (2): 163. doi:10.3828/tpr.63.2.vr76822vu248631x. ISSN 0041-0020.

- ^ Department., Singapore. Planning (1985). Revised Master plan 1985 : report of survey. The Dept. ISBN 9971-88-136-5. OCLC 20683286.

- ^ Jensen, Rolf (July 1967). "Planning, Urban Renewal, and Housing in Singapore". Town Planning Review. 38 (2): 115. doi:10.3828/tpr.38.2.eg304r3377568262. ISSN 0041-0020.

- ^ a b Dale, Ole Johan (1999). Urban planning in Singapore : the transformation of a city. New York. ISBN 967-65-3064-6. OCLC 47997114.

- ^ How, P.H (30 October 1991). "Opportunities in the Leisure Industry". URA-REDAS Joint Seminar on Living the Next Lap - Blueprints for Business.

- ^ a b c d "Concept Plan 2001 is unveiled - Singapore History". eresources.nlb.gov.sg. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Concept Plan 2011 Focus Group on Sustainability and Identity unveils draft recommendations". www.ura.gov.sg. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Meng, Meng; Zhang, Jie; Wong, Yiik Diew (February 2016). "Integrated foresight urban planning in Singapore". Urban Design and Planning. 169 (DP1): 1–13. doi:10.1680/udap.14.00061.

- ^ "Past Long-Term Plans". ura.gov.sg. Urban Redevelopment Authority. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ a b Looi, Teik Soon (2018). "5 Singapore's land transport management plan". In de Percy, Michael; Wanna, John (eds.). Road Pricing and Provision: Changed Traffic Conditions Ahead. ANU Press. pp. 73–86. ISBN 9781760462314. JSTOR j.ctv5cg9mn.13.

- ^ Cheong, Koon Hean (December 2016). "Chapter 7: The Evolution of HDB Towns". In Heng, Chye Kiang (ed.). 50 Years of Urban Planning in Singapore. World Scientific. pp. 101–125. ISBN 978-981-4656-48-1.

- ^ "Master Plan". www.ura.gov.sg. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "New Housing Concepts & More Choices". www.ura.gov.sg. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "Rejuvenating Familiar Places". www.ura.gov.sg. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "Convenient & Sustainable Mobility". www.ura.gov.sg. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Better Connectivity for All". www.ura.gov.sg. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Strengthening Economic Gateways". www.ura.gov.sg. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "A Sustainable and Resilient City of the Future". www.ura.gov.sg. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "Closing Our Resource Loops". www.ura.gov.sg. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "Creating Spaces for Our Growing Needs". www.ura.gov.sg. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Wu, Daven (2 September 2020). "SINGAPORE: THE BEST-PLANNED CITY IN THE WORLD". Discovery Cathay Pacific. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b Binder, Denis (2019). "The Deceptive Allure of Singapore's Urban Planning to Urban Planners in America". Journal of Comparative Urban Law and Policy. 3: 155–190 – via Reading Room.

- ^ "Explainer: The Climate Crisis and Singapore". New Naratif. 28 May 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "How Did Singapore Clear a Giant Forest Reserve 'By Mistake'?". www.vice.com. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Tan, Sumiko. "Home, work, play." Urban Redevelopment Authority, 1999 ISBN 981-04-1706-3

- About Us, Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA)

- Dale, O.J., Urban Planning in Singapore: The Transformation of a City. 1999, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lim, W.S.W., Cities for People: Reflections of a Southeast Asian Architect. 1990, Singapore: Select Books Pte Ltd.

- Bishop, R., J. Phillips, and W.-W. Yeo, eds. Beyond Description: Singapore Space Historicity. 2004, Routledge: New York.

- Yeoh, Brenda S. A. Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Urban Built Environment. 2003. Singapore: Singapore University Press. ISBN 9971692686

- Yuen, Belinda. Planning Singapore: From Plan to Implementation. 1998. Singapore: Singapore Institute of Planners. ISBN 9810405731

- City & The State: Singapore's Built Environment Revisited. ed. Kwok, Kenson and Giok Ling Ooi. 1997. Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies. ISBN 9780195882636

- Wong, Tiah-Chee, Yap, Adriel Lian-Ho, Four Decades of Transformation: Land Use in Singapore, 1960–2000. 2004. Cavendish Square Publishing. ISBN 9789812102706