Devils Tower

| Devils Tower (Bear Lodge) | |

|---|---|

| Matȟó Thípila (Lakota), Daxpitcheeaasáao (Crow)[1] | |

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 5,112 ft (1,558 m) NAVD 88[2] |

| Coordinates | 44°35′26″N 104°42′55″W / 44.59056°N 104.71528°W[3] |

| Geography | |

| |

| Location | Crook County, Wyoming, United States |

| Parent range | Bear Lodge Mountains, part of the Black Hills |

| Topo map | USGS Devils Tower |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Laccolith |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | William Rogers and Willard Ripley, July 4, 1893 |

| Easiest route | Durrance Route |

| Devils Tower National Monument | |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Hulett, Wyoming |

| Coordinates | 44°35′26″N 104°42′55″W / 44.59056°N 104.71528°W |

| Area | 1,346 acres (5.45 km2)[5] |

| Established | September 24, 1906[6] |

| Visitors | 499,031 (in 2017)[7] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Devils Tower National Monument |

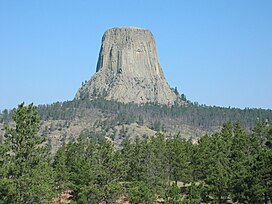

Devils Tower (also known as Bear Lodge)[8] is a butte, possibly laccolithic, composed of igneous rock in the Bear Lodge Ranger District of the Black Hills, near Hulett and Sundance in Crook County, northeastern Wyoming, above the Belle Fourche River. It rises 1,267 feet (386 m) above the Belle Fourche River, standing 867 feet (264 m) from summit to base. The summit is 5,112 feet (1,558 m) above sea level.

Devils Tower National Monument was the first United States national monument, established on September 24, 1906, by President Theodore Roosevelt.[9] The monument's boundary encloses an area of 1,347 acres (545 ha).

Name

[edit]Indigenous names for the monolith include "Bear's House" or "Bear's Lodge" (or "Bear's Tipi", "Home of the Bear", "Bear's Lair"); Cheyenne, Lakota: Matȟó Thípila, Crow: Daxpitcheeaasáao ("Home of Bears"[10]), "Aloft on a Rock" (Kiowa), "Tree Rock", "Great Gray Horn",[11] and "Brown Buffalo Horn" (Lakota: Ptehé Ǧí).[citation needed]

The name "Devil's Tower" originated in 1875 during an expedition led by Colonel Richard Irving Dodge, when his interpreter reportedly misinterpreted a native name to mean "Bad God's Tower".[11] All information signs in that area use the name "Devils Tower", following a geographic naming standard whereby the apostrophe is omitted.[12]

In 2005, a proposal to recognize several indigenous ties through the additional designation of the monolith as Bear Lodge National Historic Landmark were opposed by United States Representative Barbara Cubin, arguing that a "name change will harm the tourist trade and bring economic hardship to area communities".[13] In November 2014, Arvol Looking Horse proposed renaming the geographical feature "Bear Lodge" and submitted the request to the United States Board on Geographic Names. A second proposal was submitted to request that the U.S. acknowledge what it described as the "offensive" mistake in keeping the current name and to rename the monument and sacred site into Bear Lodge National Historic Landmark. The formal public comment period ended in fall 2015. Local state senator Ogden Driskill opposed the change.[14][15] The name was not changed.

Geology

[edit]The landscape surrounding Devils Tower is composed mostly of sedimentary rocks. The oldest rocks visible in Devils Tower National Monument were laid down in a shallow sea during the Triassic.[citation needed] This dark red sandstone and maroon siltstone, interbedded with shale, can be seen along the Belle Fourche River. Oxidation of iron minerals causes the redness of the rocks. This rock layer is known as the Spearfish Formation. Above the Spearfish Formation is a thin band of white gypsum, called the Gypsum Springs Formation, Jurassic in age.[citation needed] Overlying this formation is the Sundance Formation.[16] During the Paleocene Epoch, 56 to 66 million years ago, the Rocky Mountains and the Black Hills were uplifted.[citation needed] Magma rose through the crust, intruding into the existing sedimentary rock layers.[17]

Geologists Carpenter and Russell studied Devils Tower in the late 19th century and came to the conclusion that it was formed by an igneous intrusion.[18] In 1907, geologists Nelson Horatio Darton and C.C. O'Harra (of the South Dakota School of Mines) theorized that Devils Tower must be an eroded remnant of a laccolith.[19]

The igneous material that forms the Tower is a phonolite porphyry intruded about 40.5 million years ago,[20] a light to dark-gray or greenish-gray igneous rock with conspicuous crystals of white feldspar.[21] As the magma cooled, hexagonal columns formed (though sometimes 4-, 5-, and 7-sided columns were possible), up to 20 feet (6.1 m) wide and 600 feet (180 m) tall.

As rain and snow continue to erode the sedimentary rocks surrounding the Tower's base, more of Devils Tower will be exposed. Nonetheless, the exposed portions of the Tower still experience certain amounts of erosion. Cracks along the columns are subject to water and ice erosion. Portions, or even entire columns, of rock at Devils Tower are continually breaking off and falling. Piles of broken columns, boulders, small rocks, and stones, called scree, lie at the base of the tower, indicating that it was once wider than it is today.[17]

The geologically related Missouri Buttes are located 3.5 mi (5.6 km) northwest of Devils Tower.

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Devils Tower #2, Wyoming, 1991–2020 normals, 1959–2020 extremes: 3862ft (1177m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 65 (18) |

71 (22) |

80 (27) |

90 (32) |

97 (36) |

105 (41) |

108 (42) |

103 (39) |

103 (39) |

92 (33) |

80 (27) |

67 (19) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 51.9 (11.1) |

54.7 (12.6) |

69.8 (21.0) |

79.1 (26.2) |

85.4 (29.7) |

91.5 (33.1) |

97.2 (36.2) |

96.4 (35.8) |

92.8 (33.8) |

82.7 (28.2) |

67.6 (19.8) |

53.9 (12.2) |

99.0 (37.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 34.2 (1.2) |

36.9 (2.7) |

47.4 (8.6) |

56.6 (13.7) |

65.8 (18.8) |

76.3 (24.6) |

85.3 (29.6) |

84.6 (29.2) |

74.7 (23.7) |

59.5 (15.3) |

45.2 (7.3) |

35.4 (1.9) |

58.5 (14.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 21.0 (−6.1) |

23.8 (−4.6) |

34.1 (1.2) |

42.8 (6.0) |

52.4 (11.3) |

62.5 (16.9) |

70.0 (21.1) |

68.5 (20.3) |

58.4 (14.7) |

45.0 (7.2) |

32.1 (0.1) |

22.4 (−5.3) |

44.4 (6.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 7.8 (−13.4) |

10.8 (−11.8) |

20.8 (−6.2) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

39.1 (3.9) |

48.7 (9.3) |

54.7 (12.6) |

52.4 (11.3) |

42.1 (5.6) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

9.3 (−12.6) |

30.3 (−0.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −17.5 (−27.5) |

−14.0 (−25.6) |

−3.3 (−19.6) |

10.8 (−11.8) |

22.5 (−5.3) |

34.7 (1.5) |

42.6 (5.9) |

38.8 (3.8) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

12.3 (−10.9) |

−3.5 (−19.7) |

−13.1 (−25.1) |

−25.9 (−32.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −41 (−41) |

−44 (−42) |

−32 (−36) |

−12 (−24) |

11 (−12) |

26 (−3) |

31 (−1) |

29 (−2) |

14 (−10) |

−20 (−29) |

−35 (−37) |

−48 (−44) |

−48 (−44) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.72 (18) |

0.76 (19) |

1.13 (29) |

1.98 (50) |

2.93 (74) |

3.22 (82) |

2.14 (54) |

1.90 (48) |

1.32 (34) |

1.53 (39) |

0.78 (20) |

0.68 (17) |

19.09 (484) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.8 (22) |

9.3 (24) |

7.3 (19) |

5.3 (13) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.8 (4.6) |

6.3 (16) |

9.6 (24) |

48.8 (123.6) |

| Source 1: NOAA[22] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: XMACIS (records & monthly max/mins)[23] | |||||||||||||

Native American cultural beliefs

[edit]Devils Tower inspired many geomyths.

According to the traditional beliefs of Native American peoples, the Kiowa and Lakota, a group of girls went out to play and were spotted by several giant bears, who began to chase them. In an effort to escape the bears, the girls climbed atop a rock, fell to their knees, and prayed to the Great Spirit to save them. Hearing their prayers, the Great Spirit made the rock rise from the ground towards the heavens so that the bears could not reach the girls. The bears, in an effort to climb the rock, left deep claw marks in the sides, which had become too steep to climb. Those are the marks which appear today on the sides of Devils Tower. When the girls reached the sky, they were turned into the stars of the Pleiades.[24]

Another version tells that two Sioux boys wandered far from their village when Mato the bear, a huge creature that had claws the size of tipi poles, spotted them, and wanted to eat them for breakfast. He was almost upon them when the boys prayed to Wakan Tanka the Creator to help them. They rose up on a huge rock, while Mato tried to get up from every side, leaving huge scratch marks as he did. Finally, he sauntered off, disappointed and discouraged. The bear came to rest east of the Black Hills at what is now Bear Butte. Wanblee, the eagle, helped the boys off the rock and back to their village. A painting depicting this legend by artist Herbert A. Collins hangs over the fireplace in the visitor center at Devils Tower.

In a Cheyenne version of the story, the giant bear pursues the girls and kills most of them. Two sisters escape back to their home with the bear still tracking them. They tell two boys that the bear can only be killed with an arrow shot through the underside of its foot. The boys have the sisters lead the bear to Devils Tower and trick it into thinking they have climbed the rock. The boys attempt to shoot the bear through the foot while it repeatedly attempts to climb up and slides back down leaving more claw marks each time. The bear was finally scared off when an arrow came very close to its left foot. This last arrow continued to go up and never came down.[25]

Wooden Leg, a Northern Cheyenne, related another legend told to him by an old man as they were traveling together past the Devils Tower around 1866–1868. An Indigenous man decided to sleep at the base of Bear Lodge next to a buffalo head. In the morning he found that both he and the buffalo head had been transported to the top of the rock by the Great Medicine with no way down. He spent another day and night on the rock with no food or water. After he had prayed all day and then gone to sleep, he awoke to find that the Great Medicine had brought him back down to the ground, but left the buffalo head at the top near the edge. Wooden Leg maintained that the buffalo head was clearly visible through the old man's spyglass. At the time, the tower had never been climbed and a buffalo head at the top was otherwise inexplicable.[26]

The buffalo head gives this story special significance for the Northern Cheyenne. All the Cheyenne maintained in their camps a sacred teepee to the Great Medicine containing the tribal sacred objects. In the case of the Northern Cheyenne, the sacred object was a buffalo head.[27]

N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa) was given the name Tsoai-talee (Rock Tree Boy) by Pohd-lohk, a Kiowa elder, linking the child to the Devils Tower bear myth. To reinforce this mythic connection, his parents took him there.[28] Momaday incorporated the bear myth as unifying subtext into his 1989 novel The Ancient Child.[29]

U.S. history

[edit]Fur trappers may have visited Devils Tower, but they left no written evidence of having done so. The first documented non-Indigenous visitors were members of Captain William F. Raynolds's 1859 expedition to Yellowstone. Sixteen years later, Colonel Richard I. Dodge escorted an Office of Indian Affairs scientific survey party to the massive rock formation and coined the name Devils Tower.[30] Recognizing its unique characteristics, the United States Congress designated the area a U.S. forest reserve in 1892 and in 1906 Devils Tower became the nation's first National monument.[31]

Climbing

[edit]

As of 1994, climbing Devils Tower had increased in popularity. About 1.3% of the monument's 400,000 annual visitors climbed Devils Tower, mostly using traditional climbing techniques.[32] The first known ascent of Devils Tower by any method occurred on July 4, 1893, and is credited to William Rogers and Willard Ripley, local ranchers in the area. They completed this first ascent after constructing a ladder of wooden pegs driven into cracks in the rock face. A few of these wooden pegs are still intact and are visible on the tower when hiking along the 1.3-mile (2.1 km) Tower Trail at Devils Tower National Monument. Over the following 30 years, many climbs were made using this method before the ladder fell into disrepair.

The first ascent using modern climbing techniques was made by Fritz Wiessner with William P. House and Lawrence Coveney in 1937. Wiessner led almost the entire climb free, placing only a single piece of fixed gear, a piton, which he later regretted, deeming it unnecessary.

In 1941 George Hopkins parachuted onto Devils Tower,[33] without permission, as a publicity stunt resulting from a bet. He had intended to descend by a 1,000-foot (300 m) rope dropped to him after successfully landing on the butte, but the package containing the rope, a sledge hammer and a car axle to be driven into the rock as an anchor point slid over the edge. As the weather deteriorated, a second attempt was made to drop equipment, but Hopkins deemed it unusable after the rope became snarled and frozen due to the rain and wind. Hopkins was stranded for six days, exposed to cold, rain and 50 mph (80 km/h) winds before a mountain rescue team led by Jack Durrance, who had successfully climbed Devils Tower in 1938, finally reached him and brought him down.[34][35] His entrapment and rescue was widely covered by the media of the time.[36]

Today, hundreds of climbers scale the sheer rock walls of Devils Tower each summer. The most common route is the Durrance Route, which was the second free route established in 1938. There are many established and documented climbing routes covering every side of the tower, ascending the various vertical cracks and columns of the rock. The difficulty of these routes range from relatively easy to some of the most challenging in the world. All climbers are required to register with a park ranger before and after attempting a climb. No overnight camping at the summit is allowed; climbers return to base on the same day they ascend.[37][full citation needed]

The Tower is sacred to several Plains tribes, including the Lakota, Cheyenne and Kiowa. Because of this, many Native American leaders objected to climbers ascending the monument, considering this to be a desecration. The climbers argued that they had a right to climb the Tower, since it is on federal land. A compromise was eventually reached with a voluntary climbing ban during the month of June when the tribes are conducting ceremonies around the monument. Climbers are asked, but not required, to stay off the Tower in June. According to the PBS documentary In the Light of Reverence, approximately 85% of climbers honor the ban and voluntarily choose not to climb the Tower during the month of June. However, several climbers along with the Mountain States Legal Foundation sued the Park Service, claiming an inappropriate government entanglement with religion.[38][full citation needed][39]

Incidents

[edit]Seven people have lost their lives climbing Devils Tower in the park's 118 year history. Rescues of stranded and under-equipped climbers on the formation are common.[40] The most recent fatality was in September 2024, when a climber fell to his death while descending, leaving his climbing partner stranded without a rope on the face of the tower until help arrived.[41]

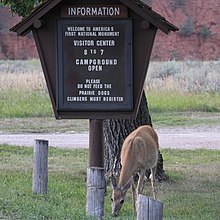

Wildlife

[edit]Devils Tower National Monument protects many species of wildlife, such as white-tailed deer, prairie dogs, and bald eagles.[42][43]

In popular culture

[edit]- The 1977 movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind used the formation as a plot element and as the location of its climactic scenes.[44][45] The film's popularity resulted in a large increase in visitors and climbers to the monument.[46]

National Register of Historic Places

[edit]Four areas of Devils Tower National Monument are on the National Register of Historic Places:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Apsáalooke Place Names Database". Little Big Horn College. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ "Devils Tower, Wyoming". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- ^ "Devils Tower". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- ^ "Devils Tower in United States of America". Protected Planet. IUCN. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ^ "Listing of acreage – December 31, 2011" (XLSX). Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved May 13, 2012. (National Park Service Acreage Reports)

- ^ . September 24, 1906 – via Wikisource.

- ^ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ "Mato Tipila, or Bear's Lodge, the stunning monolith of stone in northeastern Wyoming that settlers dubbed 'Devil's Tower.'" Jason Mark, Satellites in the High Country: Searching for the Wild in the Age of Man (2015), p. 166. "Devil's Tower, beyond the Black Hills, forms the Buffalo's Head, with the face, Bear Butte as the Buffalo's Nose, and Inyan Kaga as the Black Buffalo Horn." Jessica Dawn Palmer, The Dakota Peoples: A History of the Dakota, Lakota and Nakota through 1863 (2011), p. 203.

- ^ "Devils Tower First 50 Years" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Little Big Horn College Library". Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ a b "Why is it called Devils Tower? Some Native Americans called it Mato Tipila, meaning Bear Lodge. Other Native American names include Bear's Tipi, Home of the Bear, Tree Rock and Great Gray Horn. In 1875, on an expedition led by Col. Dodge, it is believed his interpreter misinterpreted the name to mean Bad God's Tower, later shortened to Devils Tower." NPS Frequently Asked Questions, accessed July 22, 2008.

- ^ "Since its inception in 1890, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names has discouraged the use of the possessive form—the genitive apostrophe and the 's'. The possessive form using an 's' is allowed, but the apostrophe is almost always removed. The Board's archives contain no indication of the reason for this policy." "USGS Frequently Asked Questions, #18". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ^ "Cubin Fights Devils Tower Name Change". Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ^ "Request made to change Devils Tower name to Bear Lodge". Rapid City Journal. Associated Press. June 22, 2015. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ Hancock, Laura (June 20, 2015). "Proposal could rename Devils Tower to Bear Lodge (with PDFs)". Casper Star-Tribune. Casper, WY. Retrieved September 24, 2015. PDFs include "Bear Lodge name change proposal" and "National Park Service information on name change".

- ^ Robinson, Charles (1956). "Geology of Devils Tower National Monument, USGS Bulletin 1021-I". USGS. doi:10.3133/b1021I. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b [citation needed]National Park Service: Devils Tower: Geologic Formations

- ^ Effinger, William Lloyd (1934). A Report on the Geology of Devils Tower National Monument. U.S. Department of the Interior. p. 10.

- ^ Chavis, Jason (March 21, 2018). "Facts on the Devils Tower in Wyoming". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- ^ Bassett, W.A. (October 1961). "Potassium-Argon Age of Devils Tower, Wyoming". Science. 134 (3487): 1373. Bibcode:1961Sci...134.1373B. doi:10.1126/science.134.3487.1373. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17807346. S2CID 3101604.

- ^ Woolley, A. R. (1987). Alkaline Rocks and Carbonatites of the World, Part 1: North and South America. London, British Museum (Natural History), University of Texas Press, page 126

- ^ "Devils Tower #2, Wyoming 1991–2020 Monthly Normals". Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ "xmACIS". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ Robert Burnham, Jr.: Burnham's Celestial Handbook, Vol. 3, p. 1867

- ^ Marquis, pp. 53–54

- ^ Marquis, pp. 54–55

- ^ Marquis pp. 106, 152

- ^ "N. Scott Momaday, Kiowa/Cherokee". Native American Writers. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "An Overview of Post-1960 Native American Literature". Native American Writers. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ Dodge, Richard (1996). Wayne R. Kime (ed.). The Black Hills journals of Colonel Richard Irving Dodge. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-8061-2846-1.

- ^ "Listing of National Park System Areas by State". National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ Devils Tower NM – Final Climbing Management Plan Archived November 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine National Park Service, page 4, February 1995, accessed March 13, 2009

- ^ "Parachutist George Hopkins – Devils Tower National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ Dorst, John Darwin (1999). Looking West. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 202. ISBN 0812214404.

- ^ "Parachutist gains five pounds while stranded on rock". The Victoria Advocate. United Press. October 7, 1941. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ See for instance, "Alpinists bring down man on Devil's Tower; 'rather go back than face crowd,' he says". The New York Times. October 7, 1941. p. 25.

- ^ "devilstowerclimbing.com". Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Sacred Land Film Project, Devils Tower.

- ^ Kalman, Chris (July 25, 2018). "It's Time to Rethink Climbing on Devils Tower". Outside Online. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ "NPS Incident Reports - Devils Tower National Monument". npshistory.com. Retrieved December 6, 2024.

- ^ "Fall kills climber and strands partner on Wyoming's Devils Tower". Los Angeles Times. September 25, 2024. Retrieved December 6, 2024.

- ^ "Mammals – Devils Tower National Monument". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ "Birds – Devils Tower National Monument". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ "Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)". Filmsite. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ Buckland, Warren (2006). Directed by Steven Spielberg: Poetics of The Contemporary Hollywood Blockbuster. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. pp. 111–129. ISBN 978-0-8264-1691-9.

- ^ Carlson, Allen (2009). Nature and Landscape: An Introduction to Environmental Aesthetics. Columbia University Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0231140416.

Bibliography

[edit]

- Marquis, Thomas B. (2003). Wooden Leg: A Warrior Who Fought Custer. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, Bison Books. ISBN 0-8032-8288-5. OCLC 52423964, 57065339. Wooden Leg: A Warrior Who Fought Custer at Google Books.

- Darton, Nelson Horatio (1909). Geology and water resources of the northern portion of the Black Hills and adjoining regions in South Dakota and Wyoming U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 65 (1909). doi:10.3133/pp65

External links

[edit]- Devils Tower National Monument – National Park Service

- The short film Tower of Stone is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive. Public domain, produced by National Park Service.

- 450 megapixel high-resolution photo of Devils Tower

- IUCN Category III

- Devils Tower National Monument

- 1906 establishments in the United States

- Wyoming folklore

- Archaeological sites in Wyoming

- Black Hills

- Climbing areas of the United States

- Kiowa

- Lakota mythology

- Landforms of Crook County, Wyoming

- Monoliths of the United States

- Museums in Crook County, Wyoming

- National Park Service national monuments in Wyoming

- National Register of Historic Places in Crook County, Wyoming

- Natural history museums in Wyoming

- Paleocene volcanism

- Properties of religious function on the National Register of Historic Places in Wyoming

- Protected areas of Crook County, Wyoming

- Religious places of the Indigenous peoples of North America

- Rock formations of Wyoming

- Sacred mountains of the Americas

- Volcanic plugs of the United States

- Volcanism of Wyoming

- Volcanoes of Wyoming

- Columnar basalts of the United States

- Geomyths