Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses

| Part of Nazi Germany's anti-Jewish actions, including Anti-Jewish legislation in pre-war Nazi Germany, Racial policy of Nazi Germany, Nuremberg Laws, Kristallnacht, and the Holocaust, and of the Aftermath of Political violence in Germany (1918–1933). | |

Nazi SA paramilitaries outside Israel's Department Store in Berlin. The signs read: "Germans! Defend yourselves! Don't buy from Jews." | |

| Date | April 1, 1933 |

|---|---|

| Location | Pre-war Nazi Germany |

| Target | Jewish businesses and professionals |

| Participants | Nazi Party |

The Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses (German: Judenboykott) in Germany began on April 1, 1933, and was claimed to be a defensive reaction to the anti-Nazi boycott,[1][2] which had been initiated in March 1933.[3] It was largely unsuccessful, as the German population continued to use Jewish businesses, but revealed the intent of the Nazis to undermine the viability of Jews in Germany.[4]

It was an early governmental action against the Jews of Germany by the new National Socialist government, which culminated in the "Final Solution". It was a state-managed campaign of ever-increasing harassment, arrests, systematic pillaging, forced transfer of ownership to Nazi Party activists (managed by the Chamber of Commerce), and ultimately murder of Jewish business owners. In Berlin alone, there were 50,000 Jewish-owned businesses.[5]

Earlier boycotts

[edit]Antisemitism in Germany grew increasingly pervasive after the First World War and was most prevalent in the universities. By 1921, the German student union Deutscher Hochschulring barred Jews from membership. Since the bar was racial, it included Jews who had converted to Christianity.[6] The bar was challenged by the government, leading to a referendum in which 76% of the student members voted for the exclusion.[6]

At the same time, Nazi newspapers began agitating for a boycott of Jewish businesses, and anti-Jewish boycotts became a regular feature of 1920s regional German politics with right-wing German parties becoming closed to Jews.[7]

From 1931 to 1932, SA Brownshirt thugs physically prevented customers from entering Jewish shops, windows were systematically smashed and Jewish shop owners threatened. During the Christmas holiday season of 1932, the central office of the Nazi party organized a nationwide boycott. In addition, German businesses, particularly large organizations like banks, insurance companies, and industrial firms such as Siemens, increasingly refused to employ Jews.[7] Many hotels, restaurants and cafes banned Jews from entering and the resort island of Borkum banned Jews anywhere on the island. Such behavior was common in pre-war Europe;[8][9] however in Germany, it reached new heights.

Anti-Nazi boycott of 1933

[edit]

The Anti-Nazi Boycott commencing in March 1933 was a boycott of Nazi products by foreign critics of the Nazi Party in response to antisemitism in Nazi Germany following the rise of Adolf Hitler, commencing with his appointment as Chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933. Those in the United States, the United Kingdom and other places worldwide who opposed Hitler's policies developed the boycott and its accompanying protests to encourage Nazi Germany to end the regime's anti-Jewish practices.

National boycott

[edit]

In March 1933, the Nazis won a large number of seats in the German parliament, the Reichstag. Following this victory, and partly in response to the foreign Anti-Nazi boycott of 1933,[10] there was widespread violence and hooliganism directed at Jewish businesses and individuals.[6] Jewish lawyers and judges were physically prevented from reaching the courts. In some cases the SA created improvised concentration camps for prominent Jewish anti-Nazis.[11]

Joseph Goebbels, who established the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment, announced to the Nazi party newspaper on March 31 of 1933 that "world Jewry" had ruined the reputation of the German people, and wanted to make this boycott a publicly propelled antisemitic action.[12]

On April 1, 1933, the Nazis carried out their first nationwide, planned action against Jews: a one-day boycott targeting Jewish businesses and professionals, in response to the Jewish boycott of German goods.

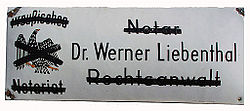

On the day of the boycott, the SA stood menacingly in front of Jewish-owned department stores and retail establishments, and the offices of professionals such as doctors and lawyers. The Propaganda Ministry wanted to catch violators of this boycott, looking to German citizens to shame other Germans who ignored the announcement and continued using Jewish stores and services.[12] The Star of David was painted in yellow and black across thousands of doors and windows, with accompanying antisemitic slogans. Signs were posted saying "Don't buy from Jews!" (Kauf nicht bei Juden!), "The Jews are our misfortune!" (Die Juden sind unser Unglück!) and "Go to Palestine!" (Geh nach Palästina!). Throughout Germany acts of violence against individual Jews and Jewish property occurred.[13]

The boycott was ignored by many individual Germans who continued to shop in Jewish-owned stores during the day.[14][1] It marked the beginning of a nationwide campaign against the Jews, but due to it's negative impact on the German economy it was met with some internal opposition. The Nazi German Austrian daily newspaper (Deutsche-Oesterreichische Tageszeitung) in one article suggested "German national wealth is being deliberately destroyed." and the Sicilian Nazi party dissaproved, seeing it as destructive to the local economy.[15]

International impact

[edit]The Nazi boycott inspired similar boycotts in other countries. In Poland the Endeks (founded by Roman Dmowski) organized boycotts of Jewish businesses across the country.[16]

In Quebec, French-Canadian nationalists organized boycotts of Jews in the 1930s.[17]

In the United States, Nazi supporters such as Father Charles Coughlin agitated for a boycott of Jewish businesses. Coughlin's radio show attracted tens of millions of listeners and his supporters organized "Buy Christian" campaigns and attacked Jews.[18] Also, Ivy League universities restricted the numbers of Jews allowed admission.[19][20]

In Austria, an organization called the Antisemitenbund had campaigned against Jewish civil rights since 1919. The organization took its inspiration from Karl Lueger, the legendary turn-of-the-century antisemitic mayor of Vienna, who inspired Hitler and had also campaigned for a boycott of Jewish businesses. Austrian campaigns tended to escalate around Christmas and became effective from 1932. As in Germany, Nazis picketed Jewish stores in an attempt to prevent shoppers from using them.[21]

In Hungary, the government passed laws limiting Jewish economic activity from 1938 onwards. Agitation for boycotts dated back to the mid-nineteenth century when Jews received equal rights.[22]

Subsequent events

[edit]The national boycott operation marked the beginning of a nationwide campaign by the Nazi party against the entire German Jewish population.

A week later, on April 7, 1933, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service was passed, which restricted employment in the civil service to "Aryans". This meant that Jews could not serve as teachers, professors, judges, or in other government positions. Most Jewish government workers, including teachers in public schools and universities, were fired, while doctors followed closely behind. However, the Jews who were war veterans were excluded from dismissal or discrimination (about 35,000 German Jews died in the First World War).[23] In 1935, the Nazis passed the Nuremberg Laws, stripping all Jews of their German citizenship, regardless of where they were born.[11] Also, a Jewish quota of 1% was introduced for the number allowed to attend universities. In the amendment published on April 11 of Part 3 of the law, which stated that all non-Aryans were to be retired from the civil service, clarification was given: "A person is to be considered non-Aryan if he is descended from non-Aryan, and especially from Jewish parents or grandparents. It is sufficient if one parent or grandparent is non-Aryan. This is to be assumed in particular where one parent or grandparent was of the Jewish religion".[24]

"Jewish" books were publicly burnt in elaborate ceremonies, and the Nuremberg laws defined who was or was not Jewish. Jewish-owned businesses were gradually "Aryanized" and forced to sell out to non-Jewish Germans.

After the Invasion of Poland in 1939, the German Nazi occupiers forced Jews into ghettos and completely banned them from public life. As World War II continued the Nazis turned to genocide, resulting in what is now known as the Holocaust.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Boycott of Jewish Businesses". Holocaust Encyclopedia. USHMM.

- ^ The History Place (2 July 2016), “Triumph of Hitler: Nazis Boycott Jewish Shops”

- ^ Berel Lang (2009). Philosophical Witnessing: The Holocaust as Presence. UPNE. pp. 131–. ISBN 978-1-58465-741-5.

- ^ Pauley, Bruce F (1998), From Prejudice to Persecution: A History of Austrian Anti-Semitism, University of North Carolina Press, pp. 200–203

- ^ Kreutzmüller, Christoph (2012). Final Sale – The Destruction of Jewish Owned Businesses in Nazi Berlin 1930–1945. Metropol-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86331-080-6.

- ^ a b c Rubenstein, Richard L.; Roth, John K. (2003). "5. Rational Antisemitism". Approaches to Auschwitz: the Holocaust and its legacy (2nd ed.). Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0664223533.

- ^ a b Longerich, Peter (2010). "1: Antisemitism in the Weimar Republic". Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews (1st ed.). USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192804365.

- ^ Karpf, Anne (8 June 2002), "We've been here before", The Guardian

- ^ Encyclopedia.com (28 Sept 2008), “Pogroms”

- ^ The Anti-Nazi Boycott of 1933, American Jewish Historical Society. Accessed January 22, 2009.

- ^ a b Michael Burleigh; Wolfgang Wippermann (1991). "4: The Persecution of the Jews". The Racial State: Germany, 1933-1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-521-39802-2.

- ^ a b Stoltzfus, Nathan (1996). "2: Stories of Jewish-German Courtship". Resistance of the Heart: Intermarriage and the Rosenstrasse Protest in Nazi Germany. Rutgers University Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-8135-2909-3.

- ^ source?

- ^ "Boycott of Jewish Businesses". Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ Stewart, Brandon Allen (2021) "The Nazi Boycott of Jewish Businesses of April 1, 1933", pp.7-9

- ^ Cang, Joel (1939). "The Opposition Parties in Poland and Their Attitude towards the Jews and the Jewish Question". Jewish Social Studies. 1 (2): 241–256.

- ^ Abella, Irving; Bialystok, Franklin (1996). "Canada: Before the Holocaust". In Wyman, David S.; Rosenzveig, Charles H. (eds.). The World Reacts to the Holocaust. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 751–753. ISBN 978-0801849695.

- ^ "Charles E. Coughlin". Holocaust Encyclopedia. USHMM.

- ^ Horowitz, Daniel (1998). Betty Friedan and the Making of The Feminine Mystique: The American Left. p. 25.

- ^ Karabel, Jerome (2005). The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Houghton Mifflin.

- ^ Bruce F. Pauley, "From Prejudice to Persecution: A History of Austrian Anti-Semitism," (North Carolina, 1992), page 201.

- ^ Randolph L. Braham, "The Christian Churches of Hungary and the Holocaust," Yad Vashem (Shoah Resource Center), pp. 1–2.

- ^ "Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, April 7, 1933". www1.yadvashem.org. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ "Documents on the Holocaust: Selected Sources on the Destruction of the Jews of Germany and Austria, Poland, and the Soviet Union," ed.by Arad, Yitzhak; Gutman, Yisrael; Margaliot, Abraham (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1987), pp. 39–42.

External links

[edit]- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – Boycott of Jewish Businesses

- Fritz Wolff Dismissal from Karstadt (1933) – 1933 Judenboykott