Earl's Court

| Earl's Court | |

|---|---|

Earl's Court Square | |

Location within Greater London | |

| Population | 9,104 (Earl's Court Ward; 2011 census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ254784 |

| • Charing Cross | 3.1 mi (5.0 km) ENE |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | SW5 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Earl's Court is a district of Kensington in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in West London, bordering the rail tracks of the West London line and District line that separate it from the ancient borough of Fulham to the west, the sub-districts of South Kensington to the east, Chelsea to the south and Kensington to the northeast. It lent its name to the now defunct eponymous pleasure grounds opened in 1887 followed by the pre–World War II Earls Court Exhibition Centre, as one of the country's largest indoor arenas and a popular concert venue, until its closure in 2014.

In practice, the notion of Earl's Court, which is geographically confined to the SW5 postal district, tends to apply beyond its boundary to parts of the neighbouring Fulham area with its SW6 and W14 postcodes to the west, and to adjacent streets in postcodes SW7, SW10 and W8 in Kensington and Chelsea.

Earl's Court is also an electoral ward of the local authority, Kensington and Chelsea London Borough Council.[2] Its population at the 2011 census was 9,104.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]Earl's Court was once a rural area, covered in orchards, green fields and market gardens. The Saxon Thegn Edwin held the lordship of the area prior to the Norman conquest. Subsequently, the land, part of the ancient manor of Kensington, was under the lordship of the de Vere family, the Earls of Oxford, descendants of Aubrey de Vere I, who held the manor of Geoffrey de Montbray, bishop of Coutances, according to the Domesday Book 1086. By circa 1095, his tenure had been converted, and he held Kensington directly from the crown. A church had been constructed there by 1104.[3]

For centuries, Earl's Court remained associated with the De Vere family, who likely lent their comital title to the manor house that became known as the "Earl's Court". Ownership later transferred through marriage in the early 17th century to the family of Sir William Cope. His daughter Isabella married Henry Rich, an ambitious courtier who was created 1st Earl of Holland in 1624. The manor subsequently passed to Rich and the house later constructed at Holland Park would bear his name for posterity as Holland House.[4] Eventually, the estate was divided into two parts. The part now known as Holland Park was sold to Henry Fox in 1762. The Earl's Court portion was retained and descended to William Edwardes, 1st Baron Kensington.[5]

The original manor house was located on the site of the present-day Earl's Court, where the Old Manor Yard is now, just by Earl's Court tube station, eastern entrance.[6] Earl's Court Farm is visible on Greenwood's map of London dated 1827.

In the late 18th century, the area began to transition from rural estates to suburban housing developments. The surgeon John Hunter had established a home and animal menagerie on the site of the former manor house in 1765. After his death in 1793, the property changed hands several times. For a period in the early 19th century it operated as a lodging house and asylum before being demolished in 1886.[7]

19th century

[edit]At the beginning of the century, the estate was generating modest rents from farmland and some building leases.[8]

There were unsuccessful speculative attempts at development in the 1820s, including failed housing development ventures. A two-mile conversion of the insanitary Counter's Creek into the Kensington Canal (1826 onwards) didn't attract substantial traffic and was followed by its eventual replacement by "Mr Punch's railway", which ceased operations six months after opening.[9][10][8] Building resumed slowly in the 1840s. By 1852 when Lord Kensington died, development was still confined to the northern part of the estate above Pembroke Road.[8]

Meanwhile, the congestion apparent in London and Middlesex for burials at the start of the century was causing public concern not least on health grounds.[11] Brompton Cemetery was duly established by Act of Parliament, laid out in 1839 and opened in 1840, originally as the West of London and Westminster Cemetery. It was consecrated by Charles James Blomfield, Bishop of London, in June 1840, and is now one of Britain's oldest and most distinguished garden cemeteries, served by the adjacent West Brompton station.

The construction of the Metropolitan District Railway in 1865–69, which eventually became London Underground's District Line and was joined after 1907 by the Piccadilly line in the 1860s, enabled the transformation of Earl's Court from farmland into a Victorian suburb. In the quarter century after 1867, Earl's Court was transformed into a loosely populated Middlesex suburb and in the 1890s a more dense parish with 1,200 houses and two churches.[8]

Eardley Crescent and Kempsford Gardens were built between 1867 and 1873, building began in Earl's Court Square and Longridge Road in 1873, in Nevern Place in 1874, in Trebovir Road and Philbeach Gardens in 1876 and Nevern Square in 1880.[8] Gunter estate was developed East of Earl's Court road between 1865 and 1896.[7]

Earl's Court's only hospital was opened in 1887 on the corner of Old Brompton Road and Finborough Road. It was named Princess Beatrice Hospital in honour of Queen Victoria's youngest daughter. The hospital closed in 1978.[12]

20th century

[edit]

For most of the century, Earl's Court was home to three notable institutions, all now gone. The first and indeed oldest school of its kind is the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art founded in 1861. It was located on the corner of Cromwell Road and Earl's Court Road, until its move to the former Royal Ballet School in Talgarth Road. The next foundation dated 1892, was the London Electronics College (formerly the London School of Telegraphy), which was located at 20 Penywern Road and in its heyday did much to expand the use of Morse code throughout the world. Already in the 1990s it was threatened with closure as technology had moved on.[13] It finally closed in 2017 having served as a further education college offering electronic engineering and IT courses. The third institution was the Poetry Society, founded in 1909 and housed at 21 Earl's Court Square. It decamped to new premises in the recently refurbished Covent Garden district of Central London in the 1990s.

Evidently, after WWI, Earl's Court had already acquired a slightly louche reputation if George Bernard Shaw is to be believed, see his Pygmalion.[14] Following the Second World War a number of Polish officers, part of the Polish Resettlement Corps, who had fought alongside Allied Forces, but were unable to return to their homeland under Soviet dominance (see Yalta Conference), opened small businesses and settled in the Earl's Court area leading to Earl's Court Road being dubbed the "Polish Corridor".[15]

During the late 1960s a large transient population of Australian, New Zealand and white South African travellers began to use Earl's Court as a UK hub and over time it gained the name "Kangaroo Valley".[16]

Population

[edit]Immediately after development, Earl's Court was sought-after and had generally middle class population, apart from some poorer pockets. Multi-occupied homes and overcrowding existed in parts of Warwick Road and around Pembroke Place, inhabited mostly by laborers and working class families. Wealthier residents with many servants occupied the larger houses on Cromwell Road and Lexham Gardens.[8]

Over time, the balance tipped from owner-occupiers to lodging houses and flats. By the 1890s, Booth's poverty maps showed the area still wealthy overall but with signs of decline setting in. The large houses built for single families were increasingly converted to flats or operated as boarding houses catering to visitors to nearby Earl's Court Exhibition Centre.[8][7]

After World War II, the area became known for its transient population. Groups settling briefly included Polish refugees, Commonwealth migrants, Arabs, Iranians and Filipinos. The influx led to overcrowded housing conditions and neglect of properties. Some stability returned from the 1970s with residents' associations forming and upgrades to the housing stock. But Earl's Court continued to be known for its rootless, shifting population compared to other more settled Kensington neighbourhoods.[8] Thus, in 1991 it had 30% annual population turnover with almost a half of inhabitants born outside of the UK.[6]: 13

The Earl's Court ward had a population of 9,104 according to the 2011 census.[1]

The recent change in the area's population is largely owed to rocketing property prices and the continued gentrification of the area. The scale of change is illustrated by the economic divide between the eastern and western areas of Earl's Court.[citation needed] Despite fighting fiercely for the exhibition centre, according to Dave Hill in The Guardian, the area's economy has been destroyed by this imbalance and the destruction of the exhibition venue.[17][failed verification]

Notable people

[edit]

The quality of the Earl's Court built environment attracted many eminent residents over the years.[6]: 9–11, 44–54

Blue plaques

[edit]- Jenny Lind (1820–1887), Swedish opera singer and teacher lived in Boltons Place in the latter part of her life.[18] A blue plaque at 189 Old Brompton Road, London, SW7, was put up in 1909.[19]

- Edwin Arnold (1832–1904), English poet and journalist, lived at 31 Bolton Gardens.[20]

- WS Gilbert (1838–1911), English dramatist and librettist, poet and illustrator, one of the two authors of the Savoy operas, lived in Harrington Gardens.

- Norman Lockyer (1836–1920), English scientist and astronomer credited with discovering the gas helium, lived at 16 Penywern Road

- Dame Ellen Terry (1847–1928), leading Shakespearian stage actress in Britain in the 1880s and 1890s, lived at 22 Barkston Gardens.

- Edmund Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby (1861–1936), British soldier and administrator famous for his role during the First World War when he led the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in the conquest of Palestine and Syria, lived at 24 Wetherby Gardens.

- Beatrix Potter (1866–1943), English naturalist, children's author, grew up in Old Brompton Road. Hers is not a blue plaque, but a multicoloured plaque on the wall of Bousfield Primary School, near the spot where her house stood before it was bombed in the Second World War

- Howard Carter (1874–1939), English archaeologist, Egyptologist and primary discoverer of the tomb of Tutankhamun, lived at 19 Collingham Gardens.

- Sir William Orpen (1878–1931), Irish portrait painter, lived at 8 South Bolton Gardens.

- Agatha Christie (1890–1971), English creator of Hercule Poirot, lived in Cresswell Place

- Alfred Hitchcock (1899–1980), English filmmaker and producer, lived at 153 Cromwell Road

- Mervyn Peake (1911–1968), painter and author of written works, such as the Gormenghast trilogy, lived at 1 Drayton Gardens

- Benjamin Britten (1913–1976), English composer, conductor, violist and pianist, lived at 173 Cromwell Road.

- Hattie Jacques (1922–1980), English comedy actress of stage, radio and screen including the Carry On films, lived at 67 Eardley Crescent. In November 1995 a blue plaque was unveiled at this house by Eric Sykes and Clive Dunn, who was a colleague from her Players' Theatre days.

- Willie Rushton (1937–1996), English satirist, cartoonist, co-founder of Private Eye, and much else, lived in Wallgrave Road.[21]

Other notable residents

[edit]- William Edwardes, 2nd Baron Kensington (1777–1852), Irish peer and British Member of parliament, original developer of the Edwardes estate, where part of Earl's Court now stands. The family originated in Pembrokeshire which accounts for Earl's Court street names such as, Nevern, Penywern and Philbeach etc.

- Augustus Henry Lane-Fox (Pitt Rivers) (1827–1900), Yorkshire-born army officer, ethnologist and archaeologist lived in 19-21 Penywern Road with 11 servants from 1879 to 1881 when he inherited a vast fortune that enabled him to upgrade to Grosvenor Gardens, London, on condition he adopted the surname, Pitt Rivers.[22] He is the founder of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford.

- Major Sir William Palliser (1830–1882), Irish-born politician and inventor, Member of Parliament for Taunton from 1880 to his death, lived in Earl's Court Square.

- Sir Robert Gunter (1831–1905), army officer, confectioner, developer and MP and his Yorkshire ancestry left their stamp on the area not merely as builders of the huge Gunter estate, but by conferring so many West Riding of Yorkshire names through part of Earl's Court, i.e. Barkston, Bramham, Collingham, Wetherby, Knaresborough etc.

- Howard Spensley (1834–1902), Australian lawyer and British Liberal politician, lived in Earl's Court Square.

- William Butler Yeats (1865–1939), Irish poet and pillar of the literary establishment, Nobel Prize winner lived at 58 Eardley Crescent during 1887 when he returned to London with his parents. His mother suffered several strokes that year.[23]

- Horace Donisthorpe (1870–1951), English myrmecologist and coleopterist, lived at 58 Kensington Mansions, Trebovir Road. Memorable for championing the renaming of the genus Lasius after him as Donisthorpea, and for discovering new species of beetles and ants, he is often considered the greatest figure in British myrmecology.

- H. G. Pelissier (1874–1913), English theatrical producer, composer and satirist, lived at 1 Nevern Square.

- Adelaide Hall (1901–1993) American jazz singer and entertainer lived at 1 Collingham Road with her husband Bert Hicks.[24]

- Stewart Granger (1913–1993), British actor, was born in Coleherne Court, Old Brompton Road, and spent most of his childhood there.[25]

- Ninette de Valois (1898–2001), founder of The Sadler's Wells, later The Royal Ballet, lived in Earl's Court Square.[26]

- Jennifer Ware (1932–2019), social activist co-founder of the Earl's Court Society among other local bodies, dubbed "The Mother of Earl's Court".[27]

- Dusty Springfield (1939–1999), popular British singer and record producer, once lived in Spear Mews.

- Syd Barrett (1946–2006) English, of Pink Floyd lived at 29 Wetherby Mansions, Earl's Court Square, from December 1968 to some time in the 1970s.[28][29][30]

- Diana, Princess of Wales (1961–1997), member of the British Royal Family, and the first wife of King Charles III, lived at 60 Coleherne Court, Old Brompton Road, from 1979 to 1981.[31][32][33]

- Sophie, Countess of Wessex (born 1965), like Princess Diana lived in Coleherne Court.

- Michael Gove (born 1967), British Conservative Party politician.[34]

- Tara Palmer-Tomkinson (1971–2017), English socialite and 90s It Girl lived (and died) in a flat in Bramham Gardens.[35][36]

Alumni of St Cuthbert's and St Matthias School

[edit]- Michael Morpurgo (born 1943), English author, poet and playwright

- Rita Ora (born 1990), Kosovo-born British singer and actress

Film locations and novels

[edit]

- Beatrix Potter's most famous work, Peter Rabbit was written in her childhood home in Bolton Gardens. The nearby Brompton Cemetery's tomb stones are said to have inspired the names of some of her much loved characters.

- No. 36 Courtfield Gardens was used in the Alvin Rakoff 1958 film Passport to Shame (aka Room 43).

- Kensington Mansions, on the north side of Trebovir Road, was the mysterious mansion block in Roman Polanski's movie Repulsion (1965), in which the sexually repressed Carole Ledoux (played by Catherine Deneuve) has a murderous breakdown.[37] The film won the Silver Berlin Bear-Extraordinary Jury Prize at the Berlin Film Festival later the same year. Kensington Mansions Block 5 featured in an episode of TV crime drama New Tricks.

- Part of the Italian film Fumo di Londra (internationally released as Smoke Over London and Gray Flannels, 1966) was shot on Redcliff Gardens. Alberto Sordi, who wrote, directed and starred in the film, won the David di Donatello for best actor. The soundtrack by Italian maestro Piero Piccioni is one of his best known.

- 64 Redcliffe Square is featured in An American Werewolf in London (1981). The film is a horror/comedy about two American tourists in Yorkshire who are attacked by a werewolf that none of the locals admit exists. The flat in the square belongs to Alex (Jenny Agutter), a pretty young nurse who becomes infatuated with one of the two American college students (David Kessler), who is being treated in hospital in London.[38]

- Earl's Court was the setting for the 1941 novel Hangover Square: A Tale of Darkest Earl's Court by novelist and playwright Patrick Hamilton. Often cited as Hamilton's finest work, it is set in 1939 in the days before war is declared with Germany. The hero George Harvey Bone innocently longs for a beautiful but cruel woman called Netta in the dark smoky pubs of Earl's Court, all the while drowning himself in beer, whisky and gin.

- Several scenes of the 1972 film Straight on Till Morning were filmed in and around Hogarth Road.

- Part of the 1985 BBC film To the World's End was shot in Earl's Court. It documented the people and the neighbourhoods along the journey of the No. 31 London bus from Camden Town to World's End, Chelsea.

- One section of V.S. Naipaul's 1987 semi-autobiographical novel The Enigma of Arrival is set in Earl's Court. In it, he describes his stay at an Earl's Court boarding house in 1950, just after his arrival in England. The Swedish Academy singled out this book as Naipaul's masterpiece when awarding him the 2001 Nobel Prize in Literature.

- The 2006 film Basic Instinct 2 used 15 Collingham Gardens for a party scene.

- Bolton Gardens was depicted in the 2006 film Miss Potter starring Renée Zellweger

- 26 Courtfield Gardens was mentioned in Richard Curtis' film About Time (2013) and was filmed on location for one of party scenes.

- The 2018 David Hare series Collateral starring Carey Mulligan and Billy Piper filmed in Bramham Gardens which was used as the home of Piper's character.

- A house in Earl's Court Square was filmed for the Grand Designs 2019 House of the Year upon its nomination by the Royal Institute of British Architects.

- In season 2 of the BBC America's Killing Eve, the exterior shot of a hotel is filmed on the corner of Cromwell Road and Collingham Road; on the boundary of Earl's Court and South Kensington.

- Season 4 of The Crown (2020) filmed outside Princess Diana's former flat in Coleherne Court.

- The reality TV show Made in Chelsea has filmed in the garden square of Courtfield Gardens (West).

- Glam rock icon David Bowie filmed the video for his 1979 hit single "D.J." off of the Lodger album here, during which he walks down the street and attracts a crowd of people—many of whom start following him—some running up to him and kissing him or whispering things in his ear—as he lip synchs the lyrics. The video was directed by David Mallet.

Local attractions

[edit]

Earl's Court may be within walking distance of High Street Kensington, Holland Park, Kensington Gardens/Hyde Park, the Royal Albert Hall, Imperial College, the Natural History, Science and Victoria and Albert Museums.

Original gaiety

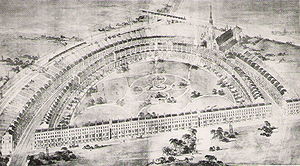

[edit]The introduction of two Underground stations, and a mass network of railways trapped a triangle of land on the border of the original parishes of Kensington and Fulham. After an unsuccessful attempt to build a Catholic school on the site, the idea of expanding entertainment in the area was probably inspired by the existence of the Lillie Bridge Grounds popular sports facility, just inside the Fulham boundary, next to West Brompton station. The person who was to bring it to fruition was John Robinson Whitley, an entrepreneur from Leeds who used the land as a show-ground for a number of years from 1887. Whitley did not meet with business success, but his aspirations for Earl's Court took hold for others to fulfil.

In 1895 the Great Wheel, a Ferris wheel, was created for the international impresario, Imre Kiralfy's Empire of India Exhibition. A plaque in the former Earls Court venue commemorated some of these events and that the reclusive Queen Victoria was an occasional visitor to the many shows put on at the site. In 1897 Kiralfy had the Empress Hall built to seat 6,000 in neighbouring Fulham and he had the Earl's Court grounds converted into the style of the 1893 Chicago White City for the Columbian Exposition. More was to come.

Not until 1937 was the Earls Court Exhibition Centre opened, with its striking Art Moderne façade facing Warwick Road. A new entrance to Earl's Court tube station was constructed to facilitate easy access to the Exhibition Centre, including direct entrance from the underground passage which connects the District and Piccadilly lines. This was however closed in the 1980s at around the time the capacity of the Exhibition Centre was expanded by the construction of a second exhibition hall, Earl's Court 2, which was opened by Princess Diana, herself a former Earl's Court resident.

In its heyday the Earls Court Exhibition Centre hosted many of the leading national trade fairs, including the annual British International Motor Show (1937-1976) and Royal Smithfield Show, as well as Crufts dog show and the combined forces Royal Tournament, which gave its name to the public house (now demolished) on the corner of Eardley Crescent. The biggest trade fairs migrated to the National Exhibition Centre at Birmingham Airport when it opened in 1988. The longest-running annual show was the Ideal Home Show in April, which attracted tens of thousands of visitors. Otherwise, it was increasingly used as a live music venue, hosting events such as the farewell concert by the boy-band Take That. At the other end of the scale, it was also used for arena-style opera performances of Carmen and Aida. Archive Movietone newsreel footage (which can be seen on YouTube) captures a unique and powerful rehearsal of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra under Wilhelm Furtwängler playing the end of Brahms' Fourth Symphony during a post-war reconciliation visit to London.

Other highlights

[edit]The Prince of Teck is a Grade II listed pub at Earl's Court Road.[39]

An early 1940s and 50s Bohemian haunt in the Earl's Court Road was the café, el Cubano, which had piped music and an authentic Italian steam Gaggia coffee machine,[40] a rarity in those days. It was few doors down from the bakery, Beaton's, whose only other outlet was on the King's Road, Chelsea. Also from that era was the theatre club, Bolton's that in 1955 transformed into arthouse cinema, the Paris Pullman in Drayton Gardens.

The Troubadour is a coffee house and a small music venue, which has hosted emerging talent since 1954 – including Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix[41] and Elvis Costello.

The Drayton Arms is a Grade II listed public house at 153 Old Brompton Road, which is also a theatrical venue.[42]

The Finborough Theatre, which opened in 1980, is the neighbourhood's local theatre.

The area also has a police box of the type used for the TARDIS time machine in the BBC Television series Doctor Who. The blue police box located outside Earl's Court underground station in Earl's Court Road is actually a replica of the traditional GPO police telephone boxes that were once a common sight in the UK from the early 1920s.[43]

Neighbourhoods

[edit]

Earl's Court is a diverse and vibrant area that comprises several distinct neighborhoods, each with its own unique charm and architectural style. The primary neighborhoods in Earl's Court are Courtfield and Earl's Court Village to the east of Earl's Court Road, and Nevern Square, Earl's Court Square, and Philbeach to the west. Together, these areas form the character of Earl's Court, reflecting the diverse styles and development patterns of the late 19th century in London.

The area is home to many multimillion-pound flats and houses in smart garden squares and residential streets. The southern boundary of Earl's Court is Old Brompton Road, with the area to the west being West Brompton, and the area to the south east being the Beach area of Chelsea. The eastern boundary of Earl's Court is Collingham Gardens and Collingham Road, east of which is South Kensington.[44]

Further west, Kensington Mansions, Nevern Square and Philbeach Gardens are built around impressive formal garden settings (access limited to key holding residents). Collingham Road and Harrington Road, also have some unique buildings, many of them used as embassies.[citation needed] "West Earl's Court", lying to the west of Earl's Court Road, is notably different in architecture. White stucco fronted "boutique" hotels in Trebovir Road and Templeton Place, and the impressive late-Victorian mansion flats and town houses of Earl's Court Square, Nevern Square and Kensington Mansions

Earl's Court Village is a triangular-shaped conservation area situated behind the bustling Earl’s Court Road and Cromwell Road, comprising Childs Place, Kenway Road, Wallgrave Road and Redfield Lane. The neighborhood retains a village-like charm, with late Georgian and Victorian terraced houses and shops. The buildings are made from a limited palette of materials, including London stock brick and stucco, with vertically sliding timber sash windows. Street trees and verdant front and rear gardens contribute to the picturesque streetscape.[45]: 6 Hidden in the middle of this area is London's smallest communal garden, "Providence Patch" built on the site of former stables serving the surrounding houses. A glimpse of the (private) gardens can be seen via the original stable entrance way in Wallgrave Road.[46]

The Courtfield Conservation Area is a residential neighborhood surrounded by Cromwell Road to the north, Earl’s Court Road to the west, and Old Brompton Road to the south. The area is characterized by Victorian formal terraces, mature gardens, and generous road widths, with buildings primarily dating from 1870 to 1900. Courtfield boasts a mix of architectural styles, including Italianate and red brick terraces, and mansion blocks. The area is also known for its picturesque streetscape, with numerous mature street trees and lushly planted garden squares.[47]: 4 Traditional cast iron railings around some areas such as the Courtfield Gardens have been restored (the originals having been removed on the orders of the MoD (UK) in 1940 for munitions during the Second World War)[47]: 39 creating a more authentic Victorian ambience.

The Philbeach Conservation Area comprises a mix of mid-Victorian terraced houses, built mainly in the Italianate style. These homes feature pale gault brick frontages with stucco dressings, Roman Doric projecting porches, and sash windows. The area also includes St Cuthbert's Church, a Grade I listed building, and Philbeach Gardens.[48]: 6

Nevern Square Conservation Area showcases the evolution of architectural styles in the late 19th century. The area includes mid-late Victorian terraced houses, mansion flats, and the Grade II listed Earl's Court Underground Station. The main focus is Nevern Square, a private garden square surrounded by elegant homes. Development in the area began in the Italianate style, transitioning to the Domestic Revival style, and finally to the construction of mansion flats. Gardens and green corridors play an essential role in the area's character.[49]: 6

Earl's Court Square Conservation Area, a predominantly residential area, lies to the south, surrounded by busy thoroughfares on the east, west, and south. The residential streets consist of terraced housing, semi-detached houses, and mansion blocks, all built in the mid-late Victorian period. The buildings share a common palette of materials, including yellow or red stock brick, stucco, and stone, with timber sash windows or casement windows. The area also has a commercial character along the southeastern boundary on Earl's Court Road. Mature street trees, verdant planting, and communal gardens contribute to the area's picturesque streetscape.[50]: 3

Garden squares and mews

[edit]

The layout of much of the Earl's Court differed in some respects from earlier developments, such as ones to the south of Old Brompton Road. Unlike the grand spaces of The Boltons or the more modest Ifield Road, the Gunter estate was characterized by the typical Kensington "Gardens" – rows of houses backing directly onto private (but communal) ornamental grounds. Even though not every house backed directly onto a garden, the houses still fronted onto the streets in orthodox fashion, rather than presenting their "backs" to the streets. Besides Collingham Gardens designed by Ernest George and Harold Peto, the rear views of the houses across the gardens were orderly and uniform.[7]

Considerable importance was placed on the mews, with Hesper Mews laid out in 1884-85 as the largest and finest stable block under the supervision of various architects. Colbeck Mews (1876-84) also had architect-designed stables by George and Peto. Most mews had the typical arched entrance, and some like Hesper Mews presented attractive flank fronts to adjacent streets. Despite the prominence of mews, with over twice as many than south of Old Brompton Road, the number of individual units was only about a quarter of the houses.[7]

Earl's Court adds to the Royal Borough's tally of almost 50 garden squares. Within SW5 they include:

- Barkston Gardens

- Bina Gardens

- Bolton Gardens

- Bramham Gardens

- Collingham Gardens

- Courtfield Gardens

- Earl's Court Square

- Gledhow Gardens

- Nevern Square

- Philbeach Gardens

- Wetherby Gardens

The mews include:

- Courtfield Mews

- Dove Mews

- Farnell Mews

- Gasper Mews

- Hesper Mews

- Kramer Mews

- Laverton Mews

- Morton Mews

- Old Manor Yard

- Redfield Mews

- Spear Mews

- Wetherby Mews

Gay area

[edit]

Earl's Court preceded Soho and Vauxhall as London's premier centre of gay nightlife, though the number of businesses aimed mostly at gay men has dwindled to a single retail outlet and bar, as Soho and Vauxhall established themselves as the new focus. The first public nightclub aimed at a gay clientele, the Copacabana, opened in Earl's Court Road in the late 1970s, but was re-themed as a general venue in the late 1990s. The bar upstairs, Harpoon Louie's (later Harpo's and later still Banana Max), was until the late 1980s among the most popular gay bars in London. It is now a Jollibee restaurant.

The oldest pub on the site was the Lord Ranelagh pub (opposite the former Princess Beatrice Hospital) now demolished, that in 1964 spearheaded the local demand for live entertainment. A young, non-gay, male band, the Downtowners, attracted considerable attention. They persuaded many of the local cross-dressers to come into the pub and perform. Thus, the Queen of the Month contest was born. Every Saturday night the pub was packed to capacity. The show ran from September 1964 until May 1965 when the News of the World ran an article entitled 'This show must not go on'. On that Sunday night the pub was so packed that every table and chair had to be removed. Crowds spilled out on to the pavement onto Old Brompton Road. The police closed the show. Many well-known celebrities were among the clientele and the Lord Ranelagh, in its incarnations as Bromptons and finally, Infinity, is considered to have played a role in the history of gay liberation. In the 1970s it became a notorious leather bar, with blacked-out windows, attracting an international crowd including the likes of Freddie Mercury, Kenny Everett, and Rudolf Nureyev. The pub was demolished after its closure.

The Pembroke pub, formerly the Coleherne, dates from the 1880s and had a long history of attracting a bohemian clientele before becoming known as a gay pub. A lifelong resident of Earl's Court Square and social activist, Jennifer Ware, recollects as a child being taken there to Sunday lunch in the 1930s, when drag entertainers performed after lunch had finished.[51] It also became infamous as the stalking ground for three separate serial killers from the 1970s to the 1990s: Dennis Nilsen, Michael Lupo and Colin Ireland. It sought to lighten its image with a makeover in the mid-1990s to attract a wider clientele; to no avail, as in December 2008 it underwent a major refurbishment and repositioned itself as a gastro pub with a new name.[52]

Transport

[edit]Tube stations

[edit]

- Earl's Court tube station, served by the District and Piccadilly lines

- West Brompton station, served by the District line's Wimbledon branch and London Overground

- Gloucester Road tube station, served by the Circle, District and Piccadilly lines

Bus routes

[edit]These have replaced the former routes 31 that used to run from World's End to Kilburn and the old bus route 74B that ran from Hammersmith to London Zoo.

Major roads

[edit]When Ernest Marples was transport minister (1962-1964), it was decided to turn part of Earl's Court Road, from the junction with Pembroke Road, into a southward one-way arterial road and the parallel Warwick Road as the northward arterial road, going past the then Earl's Court Exhibition Centre. A third arterial road at right angles to the former two is the Cromwell Road, designated as the A4 that carries traffic between central London and Heathrow Airport and beyond to the West. A fourth road that creates a box with the other three is the A 3218, Old Brompton Road, better described as a trunk road.

Nearby places

[edit]

- Brompton Cemetery, Grade I Listed

- Stamford Bridge, home of Chelsea F.C.

- Olympia Exhibition Centre, West Kensington

Districts

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Kensington and Chelsea Ward population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ "Earl's Court Ward Profile" (PDF). rbkc.gov.uk. Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Victoria County History of England, Middlesex, vol. I, 116-7.

- ^ Aikin-Kortright, Fanny, ed. (1870). "Earl's Court, Kensington". The Court Suburb. Vol. 2. London.

- ^ Bellew, rev. J. C. M. (1867). "Holland House". The Broadway Annual. pp. 47–55.

- ^ a b c Richard Tames, Earl's Court and Brompton Past. Historical Publications, London, 2000

- ^ a b c d e Hobhouse, Hermione, ed. (1986). "The Gunter estate". Survey of London: Volume 42, Kensington Square To Earl's Court. London. pp. 196–214.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Hermione Hobhouse, ed. (1986). 'The Edwardes estate: South of West Cromwell Road', in Survey of London. Vol. 42, Kensington Square To Earl's Court. London. pp. 300–321.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) [accessed 22 April 2019]. - ^ Nicholas Barton (1992). The Lost Rivers of London. London: Historical publications. p. 71. ISBN 0-948667-15-X.

- ^ Arthur William à Beckett, The à Becketts of Punch, 1903, reprinted by Richardson, 1969, ISBN 978-1115475303

- ^ Sheppard, F.H.W., ed. (1983). "Brompton". Survey of London. Vol. 41. London: London City Council. pp. 246–252. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ The Lost Hospitals of London - Princess Beatrice, SW5

- ^ Sir Nicholas Scott (Chelsea). "London Electronics College". House of Commons: Hansard vol 275 cc685-92 685 1.29 pm. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ "Pygmalion, His Majesty's Theatre, 1914, review of George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion in London 100 years ago. Here is the original Telegraph review". The Daily Telegraph. 19 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ In the SW5 postal area alone, Polish outlets included: The Marine Officers' Club in Wetherby Gdns., the Airmen's Club in Collingham Gdns, the displaced Polish Women's Hostel in Warwick Road (Dom Polek), two medical practices, Warwick Road and Penywern Road, three dental practices in Cresswell Gdns., Gledhow Gdns. and Wetherby Gdns., a pharmacy, Grabowski in Earl's Court Road (later the owner, Mateusz Grabowski, opened the Grabowski Gallery in Chelsea and endowed a professorial chair at Cambridge University), three hotels: the Strathcona Hotel in Cromwell Road, the Lord Jim Hotel and the Oxford Hotel in Penywern Road, two booksellers and publishers: B. Świderski in Warwick Road, Orbis Books (London) in Kenway Road, three delicatessens: Chromiński and Kern's in Old Brompton Road, Ryszytny in Kenway Road and Finborough Road, two travel and parcel despatch companies: Haskoba in Cromwell Road, and Tazab Travel in Old Brompton Road, which later became a Polish-owned electrical shop and one undertaker: Łysakowski in Old Brompton Road, opp. Brompton Cemetery.

- ^ To the World's End: Scenes and Characters On a London Bus Route, director Jonathan Gili, BBC, 1985.

- ^ Dave Hill (15 December 2014). "Earl's Court final curtain is sad reflection on Boris Johnson's London". The Guardian.

- ^ Jamie Barras (12 August 2007), Jenny Lind, retrieved 16 March 2024

- ^ "English Heritage". www.english-heritage.org.uk. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ "- English Heritage". english-heritage.org.uk.

- ^ "Stock Photo - Home of William Rushton Author Rowhouse on Wallgrave Road Kensington near Earls Court Road London England UK".

- ^ "Pitt-Rivers' homes". web.prm.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ "William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) - Life (1)". www.ricorso.net. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ Photograph of Adelaide Hall with her private secretary standing outside her London home at Collingham Road:https://myspace.com/adelaidehall/mixes/classic-my-photos-162119/photo/9512318

- ^ Colherne Court East in 1913 – 20th Century. Rbkc.gov.uk (20 April 2005)

- ^ "London Open Garden Squares Weekend: top 20 to visit". The Daily Telegraph. 14 June 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Spotlight on Jennifer Ware". Kensington and Chelsea Social Council. 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Syd's London Homes:http://www.sydbarrettpinkfloyd.com/2007/03/syds-london-homes.html

- ^ "Syd Barrett, Wetherby Mansions, Earl's Court Square, Kensington, London". Notable Abodes.

- ^ "Syd Barrett in the bedroom of his Earl's Court flat, 1967". Pinterest.

- ^ "BBC News | UK | No takers for Diana's flat". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ "Princess Diana's Flat". www.shadyoldlady.com. Retrieved 16 March 2024.

- ^ Princess Diana – Gym – Earl's Court, west London Archived 31 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Prints.paphotos.com (21 August 1997)

- ^ Coates, Sam (16 November 2018). "Gove on edge after rejecting new job". The Times. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Celebrities mourn tragic death of socialite Tara Palmer-Tomkinson". 8 February 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Furness, Hannah; Steafel, Eleanor; Evans, Martin; Yorke, Harry (8 February 2017). "Tara Palmer-Tomkinson had not been seen for nearly a week before she was found dead, neighbours claim". The Telegraph. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Film locations for Repulsion (1965) Archived 12 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Movie-locations.com.

- ^ "IMDb: Most Popular Titles With Location Matching "64 Coleherne Road, Earl's Court, London, England, UK"". IMDb.

- ^ Historic England. "Prince of Teck public house (1031501)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ "Our legacy". Gaggia. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019.

- ^ "The Troubadour has been saved!". Evening Standard. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Historic England. "Drayton Arms public house (1225769)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ^ h2g2 – The Earl's Court Police Box, London, UK. BBC.

- ^ [1]. Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

- ^ "Earl's Court Village Conservation Area Appraisal" (PDF). RBKC. February 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ 'Earl's Court Village and Earl's Court Gardens area', in Survey of London: Volume 42, Kensington Square To Earl's Court, ed. Hermione Hobhouse (London, 1986), pp. 215-224. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol42/pp215-224 [accessed 31 March 2023].

- ^ a b "Courtfield Conservation Area Appraisal" (PDF). RBKC. 14 December 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Philbeach Conservation Area Appraisal" (PDF). RBKC. October 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Nevern Square Conservation Area Appraisal" (PDF). RBKC. October 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Earl's Court Square Conservation Area Appraisal" (PDF). RBKC. 6 June 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Jennifer Ware Obituary". The Times. 16 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019. (subscription needed)

- ^ [2] Archived 15 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine