Penning trap

A Penning trap is a device for the storage of charged particles using a homogeneous magnetic field and a quadrupole electric field. It is mostly found in the physical sciences and related fields of study as a tool for precision measurements of properties of ions and stable subatomic particles, like for example mass,[1] fission yields and isomeric yield ratios. One initial object of study was the so-called geonium atoms, which represent a way to measure the electron magnetic moment by storing a single electron. These traps have been used in the physical realization of quantum computation and quantum information processing by trapping qubits. Penning traps are in use in many laboratories worldwide, including CERN, to store and investigate anti-particles such as antiprotons.[2] The main advantages of Penning traps are the potentially long storage times and the existence of a multitude of techniques to manipulate and non-destructively detect the stored particles.[3][4] This makes Penning traps versatile tools for the investigation of stored particles, but also for their selection, preparation or mere storage.

History

[edit]The Penning trap was named after F. M. Penning (1894–1953) by Hans Georg Dehmelt (1922–2017) who built the first trap. Dehmelt got inspiration from the vacuum gauge built by F. M. Penning where a current through a discharge tube in a magnetic field is proportional to the pressure. Citing from H. Dehmelt's autobiography:[5]

"I began to focus on the magnetron/Penning discharge geometry, which, in the Penning ion gauge, had caught my interest already at Göttingen and at Duke. In their 1955 cyclotron resonance work on photoelectrons in vacuum Franken and Liebes had reported undesirable frequency shifts caused by accidental electron trapping. Their analysis made me realize that in a pure electric quadrupole field the shift would not depend on the location of the electron in the trap. This is an important advantage over many other traps that I decided to exploit. A magnetron trap of this type had been briefly discussed in J.R. Pierce's 1949 book, and I developed a simple description of the axial, magnetron, and cyclotron motions of an electron in it. With the help of the expert glassblower of the Department, Jake Jonson, I built my first high vacuum magnetron trap in 1959 and was soon able to trap electrons for about 10 sec and to detect axial, magnetron and cyclotron resonances." – H. Dehmelt

H. Dehmelt shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1989 for the development of the ion trap technique.

Operation

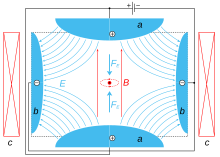

[edit]Penning traps use a strong homogeneous axial magnetic field to confine particles radially and a quadrupole electric field to confine the particles axially.[6] The static electric potential can be generated using a set of three electrodes: a ring and two endcaps. In an ideal Penning trap the ring and endcaps are hyperboloids of revolution. For trapping of positive (negative) ions, the endcap electrodes are kept at a positive (negative) potential relative to the ring. This potential produces a saddle point in the centre of the trap, which traps ions along the axial direction. The electric field causes ions to oscillate (harmonically in the case of an ideal Penning trap) along the trap axis. The magnetic field in combination with the electric field causes charged particles to move in the radial plane with a motion which traces out an epitrochoid.

The orbital motion of ions in the radial plane is composed of two modes at frequencies which are called the magnetron and the modified cyclotron frequencies. These motions are similar to the deferent and epicycle, respectively, of the Ptolemaic model of the solar system.

The sum of these two frequencies is the cyclotron frequency, which depends only on the ratio of electric charge to mass and on the strength of the magnetic field. This frequency can be measured very accurately and can be used to measure the masses of charged particles. Many of the highest-precision mass measurements (masses of the electron, proton, 2H, 20Ne and 28Si) come from Penning traps.

Buffer gas cooling, resistive cooling, and laser cooling are techniques to remove energy from ions in a Penning trap. Buffer gas cooling relies on collisions between the ions and neutral gas molecules that bring the ion energy closer to the energy of the gas molecules. In resistive cooling, moving image charges in the electrodes are made to do work through an external resistor, effectively removing energy from the ions. Laser cooling can be used to remove energy from some kinds of ions in Penning traps. This technique requires ions with an appropriate electronic structure. Radiative cooling is the process by which the ions lose energy by creating electromagnetic waves by virtue of their acceleration in the magnetic field. This process dominates the cooling of electrons in Penning traps, but is very small and usually negligible for heavier particles.

Using the Penning trap can have advantages over the radio frequency trap (Paul trap). Firstly, in the Penning trap only static fields are applied and therefore there is no micro-motion and resultant heating of the ions due to the dynamic fields, even for extended 2- and 3-dimensional ion Coulomb crystals. Also, the Penning trap can be made larger whilst maintaining strong trapping. The trapped ion can then be held further away from the electrode surfaces. Interaction with patch potentials on the electrode surfaces can be responsible for heating and decoherence effects and these effects scale as a high power of the inverse distance between the ion and the electrode.

Fourier-transform mass spectrometry

[edit]Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (also known as Fourier-transform mass spectrometry) is a type of mass spectrometry used for determining the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ions based on the cyclotron frequency of the ions in a fixed magnetic field.[7] The ions are trapped in a Penning trap where they are excited to a larger cyclotron radius by an oscillating electric field perpendicular to the magnetic field. The excitation also results in the ions moving in phase (in a packet). The signal is detected as an image current on a pair of plates which the packet of ions passes close to as they cyclotron. The resulting signal is called a free induction decay (fid), transient or interferogram that consists of a superposition of sine waves. The useful signal is extracted from this data by performing a Fourier transform to give a mass spectrum.

Single ions can be investigated in a Penning trap held at a temperature of 4 K. For this the ring electrode is segmented and opposite electrodes are connected to a superconducting coil and the source and the gate of a field-effect transistor. The coil and the parasitic capacitances of the circuit form a LC circuit with a Q of about 50 000. The LC circuit is excited by an external electric pulse. The segmented electrodes couple the motion of the single electron to the LC circuit. Thus the energy in the LC circuit in resonance with the ion slowly oscillates between the many electrons (10000) in the gate of the field effect transistor and the single electron. This can be detected in the signal at the drain of the field effect transistor.

Geonium atom

[edit]A geonium atom is a pseudo-atomic system that consists of a single electron or ion stored in a Penning trap which is 'bound' to the remaining Earth, hence the term 'geonium'.[6] The name was coined by H.G. Dehmelt.[8]

In the typical case, the trapped system consists of only one particle or ion. Such a quantum system is determined by quantum states of one particle, like in the hydrogen atom. Hydrogen consists of two particles, the nucleus and electron, but the electron motion relative to the nucleus is equivalent to one particle in an external field, see center-of-mass frame.

The properties of geonium are different from a typical atom. The charge undergoes cyclotron motion around the trap axis and oscillates along the axis. An inhomogeneous magnetic "bottle field" is applied to measure the quantum properties by the "continuous Stern-Gerlach" technique. Energy levels and g-factor of the particle can be measured with high precision.[8] Van Dyck, et al. explored the magnetic splitting of geonium spectra in 1978 and in 1987 published high-precision measurements of electron and positron g-factors, which constrained the electron radius.[citation needed]

Single particle

[edit]In November 2017, an international team of scientists isolated a single proton in a Penning trap in order to measure its magnetic moment to the highest precision to date.[9] It was found to be 2.79284734462(82) nuclear magnetons. The CODATA 2018 value matches this.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ Eronen, T.; Kolhinen, V. S.; Elomaa, V. -V.; Gorelov, D.; Hager, U.; Hakala, J.; Jokinen, A.; Kankainen, A.; Karvonen, P.; Kopecky, S.; Moore, I. D. (2012-04-18). "JYFLTRAP: a Penning trap for precision mass spectroscopy and isobaric purification". The European Physical Journal A. 48 (4): 46. Bibcode:2012EPJA...48...46E. doi:10.1140/epja/i2012-12046-1. ISSN 1434-601X. S2CID 119825256.

- ^ "Penning Trap | ALPHA Experiment". alpha.web.cern.ch. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ Major, F. G. (2005). Charged particle traps : physics and techniques of charged particle field confinement. V. N. Gheorghe, G. Werth. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-22043-7. OCLC 62771233.

- ^ Vogel, Manuel (2018). Particle confinement in Penning traps : an introduction. Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-319-76264-7. OCLC 1030303331.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Hans G. Dehmelt - Biographical". Nobel Prize. 1989. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Brown, L.S.; Gabrielse, G. (1986). "Geonium theory: Physics of a single electron or ion in a Penning trap" (PDF). Reviews of Modern Physics. 58 (1): 233–311. Bibcode:1986RvMP...58..233B. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.58.233. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-13. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- ^ Marshall, A. G.; Hendrickson, C. L.; Jackson, G. S. (1998). "Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry: A primer". Mass Spectrometry Reviews. 17 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2787(1998)17:1<1::AID-MAS1>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 9768511.

- ^ a b Dehmelt, Hans (1988). "A single atomic particle forever floating at rest in free space: New value for electron radius". Physica Scripta. T22: 102–110. Bibcode:1988PhST...22..102D. doi:10.1088/0031-8949/1988/T22/016. S2CID 250760629.

- ^ Schneider, Georg; Mooser, Andreas; Bohman, Matthew; et al. (2017). "Double-trap measurement of the proton magnetic moment at 0.3 parts per billion precision". Science. 358 (6366): 1081–1084. Bibcode:2017Sci...358.1081S. doi:10.1126/science.aan0207. PMID 29170238.

- ^ "2018 CODATA Value: proton magnetic moment to nuclear magneton ratio". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

External links

[edit]- Nobel Prize in Physics 1989

- The High-precision Penning Trap Mass Spectrometer SMILETRAP in Stockholm, Sweden

- High-precision mass determination of unstable nuclei with a Penning trap mass spectrometer at ISOLDE/CERN, Switzerland

- High-precision mass measurements of rare isotopes using the LEBIT and SIPT Penning traps at the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory, USA

- High-precision mass measurements of short-lived isotopes using the TITAN Penning trap at TRIUMF in Vancouver, Canada