German question

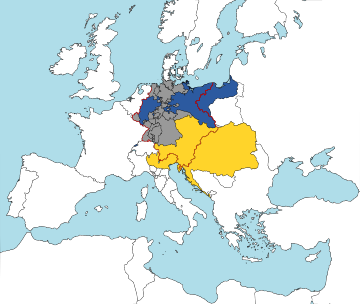

Caption reads: "German Unity. A Tragedy in one Act."

The "German question" was a debate in the 19th century, especially during the Revolutions of 1848, over the best way to achieve a unification of all or most lands inhabited by Germans.[1] From 1815 to 1866, about 37 independent German-speaking states existed within the German Confederation. The Großdeutsche Lösung ("Greater German solution") favored unifying all German-speaking peoples under one state, and was promoted by the Austrian Empire and its supporters. The Kleindeutsche Lösung ("Lesser German solution") sought to unify only the northern German states and did not include any part of Austria (either its German-inhabited areas or its areas dominated by other ethnic groups); this proposal was favored by the Kingdom of Prussia.

The solutions are also referred to by the names of the states they proposed to create, Kleindeutschland and Großdeutschland ("Lesser Germany" and "Greater Germany"). Both movements were part of a growing German nationalism. They also drew upon similar contemporary efforts to create a unified nation state of people who shared a common ethnicity and language, such as the Unification of Italy and the Serbian Revolution.

During the Cold War, the term was repurposed to refer to the matters pertaining to the division, and re-unification, of Germany.[2]

Background

[edit]

There is, in political geography, no Germany proper to speak of. There are Kingdoms and Grand Duchies, and Duchies and Principalities, inhabited by Germans, and each separately ruled by an independent sovereign with all the machinery of State. Yet there is a natural undercurrent tending to a national feeling and toward a union of the Germans into one great nation, ruled by one common head as a national unit.

— The New York Times, July 1, 1866[3]

Over the centuries, the Holy Roman Empire had to cope with a continuous loss of authority to its constituent estates. The disastrous Thirty Years' War proved especially detrimental to the Holy Roman Emperor's authority, as the mightiest two entities within it, the Austrian Habsburg monarchy and Brandenburg-Prussia, evolved into rivalling European absolute powers with territory reaching far beyond Holy Roman Imperial borders. Meanwhile, the many smaller estates splintered further. In the 18th century the Holy Roman Empire consisted of hundreds of separate territories governed by distinct authorities.

This rivalry between Austria and Prussia resulted in the War of the Austrian Succession, and then outlasted the French Revolution and Napoleon's domination of Europe. Facing the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, the ruling House of Habsburg proclaimed the Austrian Empire in 1804. On August 6, 1806, Habsburg Emperor Francis II abdicated the throne of the Holy Roman Empire in the course of the Napoleonic Wars with France. The 1815 restoration by the Final Act of the Vienna Congress established the German Confederation, which was not a nation but a commonwealth association of sovereign states on the territory of the former Holy Roman Empire.

While a number of factors swayed allegiances in the debate, the most prominent was religion. The Großdeutsche Lösung would have implied a dominant position for Catholic Austria, the largest and most powerful German state of the early 19th century. As a result, Catholics and Austria-friendly, mostly southern states usually favored Großdeutschland. A unification of Germany led by Prussia would mean the domination of the new state by the Protestant House of Hohenzollern, a more palatable option to Protestant, mostly northern German states. Another complicating factor was the Austrian Empire's inclusion of a large number of non-Germans, such as Hungarians, Czechs, South Slavs, Italians, Poles, Ruthenians, Romanians and Slovaks. Additional complication was that the Austrians were reluctant to enter a unified Germany if it meant giving up their non-German speaking territories.

March Revolution

[edit]

In 1848, German liberals and nationalists united in revolution, forming the Frankfurt Parliament. The Greater German movement within this National Assembly demanded the unification of all German-populated lands into one nation. In general or to an extent, the left favored a republican Großdeutsche Lösung, whereas the liberal center favored the Kleindeutsche Lösung with a constitutional monarchy.

Those supporting the Großdeutsche position argued that since the Habsburgs had ruled the Holy Roman Empire for almost 400 years from 1440 to 1806 (the only break coming from the extinction of the Habsburg male line in 1740 to the election of Francis I in 1745), Austria was best suited to lead the unified nation. However, Austria posed a problem because the Habsburgs ruled large chunks of non-German-speaking territory. The largest such area was the Kingdom of Hungary, which also included large Slovak, Romanian and Croat populations. Austria further comprised numerous possessions with predominantly non-German populations, including Czechs in the Bohemian lands, Poles, Rusyns and Ukrainians in the Galician province, Slovenes in Carniola, and Italians in Lombardy–Venetia and Trentino, which was still incorporated into the Tyrolean crown land, altogether making up the larger part of the Austrian Empire. Except for Bohemia, Carniola, and Trento, these territories were not part of the German Confederation because they had not (in some cases not lately) been part of the former Holy Roman Empire, and none of them desired to be included in a German nation-state. The Czech politician František Palacký explicitly rejected the offered mandate to the Frankfurt assembly, stating that the Slavic lands of the Habsburg Empire were not a subject of German debates. On the other hand, for Austrian prime minister Prince Felix of Schwarzenberg, only the accession of the Habsburg Empire as a whole was acceptable because it had no intention to part from its non-German possessions and dismantle in order to remain in an all-German Empire.

Thus, some members of the assembly, and Prussia in particular, promoted the Kleindeutsche Lösung, which excluded the whole Austrian Empire with its German and its non-German possessions. They argued that Prussia, as the only Great Power with a predominantly German-speaking population, was best qualified to lead the newly unified Germany. Yet, the drafted constitution provided for the possibility for Austria to join without its non-German possessions later. On March 30, 1849, the Frankfurt parliament offered the German Imperial crown to King Frederick William IV of Prussia, who rejected it. The revolution failed and several subsequent attempts by Prince Schwarzenberg to more closely unite the German Confederation headed by Austria (Greater Austria proposal) came to nothing.

Austro-Prussian War and Franco-Prussian War

[edit]

These efforts were finally terminated by Austria's humiliating defeat in 1866 Austro-Prussian War. After the Peace of Prague, the Prussian Minister President Otto von Bismarck, now at the helm of German politics, pursued the expulsion of Austria and managed to unite all German states except Austria under Prussian leadership, while the Habsburg lands were shaken by ethnic nationalist conflicts, only superficially resolved with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867.

At the same time, Bismarck established the North German Confederation, seeking to prevent the Austrian and Bavarian Catholics in the south from being a predominant force in a mainly Protestant Prussian Germany. He successfully used the Franco-Prussian War to convince the other German states, including the Kingdom of Bavaria, to stand with Prussia against the Second French Empire; Austria-Hungary did not participate in the war. After Prussia's speedy victory, the debate was settled in favor of the Kleindeutsche Lösung in 1871. Bismarck used the prestige gained from the victory to maintain the alliance with Bavaria and proclaimed the German Empire. Protestant Prussia became the dominant power of the new state, and Austria-Hungary was excluded, remaining a separate polity. The Lesser German solution prevailed.

Later influence

[edit]

The idea of Austrian territories with a significant German-speaking population joining a Greater German state was maintained by some circles both in Austria-Hungary and Germany. It was again promoted after the close of World War I and the dissolution of the Austro–Hungarian monarchy in 1918 by the proclamation of the rump state, German Austria. Proponents attempted to incorporate German Austria into the German Weimar Republic. However, this was prohibited by the terms of both the Treaty of Saint-Germain and the Treaty of Versailles, though Austrian political parties such as the Greater German People's Party and the Social Democrats pursued this idea regardless.[4]

In 1931, there was an attempt to create a customs union between the Weimar Republic and Austria. The move was protested by France, and bankers such as Henry Strakosch of Austria, who later became a financier of Winston Churchill. Large-volume money transfers followed, making the customs union impractical as the economic crisis deepened.

In Germany, Adolf Hitler, an Austrian German by birth, had been a firm proponent of the unification of Germany and Austria. A demand for a Greater Germany was included in a 1920 party platform of the Nazi Party.[5] Hitler's election in Germany set into motion increased pressure for a merger between Germany and Austria that swayed many Austrian politicians. But fascist Italy, despite its friendly relations with Hitler, strongly opposed any kind of merger of Austria into Germany, and pressured and threatened Austrian politicians from pursuing such a course. Austria, meanwhile, adopted Austrofascism which focused on the history of Austria and opposed the absorption of Austria into Nazi Germany (according to the belief that Austrians were "better Germans").[6] Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg (1934–1938) called Austria the "better German state". Nevertheless, German nationalists' desire for a unified nation-state incorporating all Germans into a Greater Germany persisted and, in time, Mussolini's Italy became distracted by its 1936 invasion of Ethiopia, leading to a stretch of resources and less willingness to intervene in Austria.

In 1938, Hitler's long-desired union between his birthplace, Austria, and Germany (Anschluss) was completed, which violated the terms of the Treaty of Versailles; the League of Nations was unable to enforce the ban on such a union. The Anschluss was met with overwhelming approval of the German-Austrian people, and was confirmed by a referendum shortly after.[7] The unification process was reinforced one month later by a referendum, supported by an overwhelming majority. In contrast to the political situation in the 19th century, when Austria had controlled large areas of non-German peoples, Austria became the subordinate partner in the new unified German-speaking state. From 1938 to 1942, the former state of Austria was referred to as Ostmark ("Eastern March") by the new German state. In a reference to the 19th-century "Greater German solution", the enlarged state was referred to as the Großdeutsches Reich ("Greater German Reich") and colloquially as Großdeutschland. The names were informal at first, but the change to Großdeutsches Reich became official in 1943. As well as Germany (pre-World War II borders), Austria, and Alsace-Lorraine, the Großdeutsches Reich included the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, Sudetenland, Bohemia and Moravia, the Memel Territory, the Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, the Free State of Danzig, and the "General Government" territories (territories of Poland under German military occupation).

-

The Greater German Reich in 1943

East and West Germany and reunification

[edit]

This unification lasted only until the end of World War II. With the defeat of the Nazi regime in 1945, "Greater Germany" was separated into West Germany, East Germany, and Austria by the Allied Powers. Austria was also occupied but given full sovereignty by the 1955 Austrian State Treaty which among other things required Austria to renounce any designs on uniting with Germany. Austrian neutrality was affirmed in a separate but related act. Furthermore, Germany was stripped of much of historic eastern Germany (i.e. the bulk of Prussia), most of which was annexed to Poland, with a small portion annexed to the Soviet Union (today's Kaliningrad Oblast). Luxembourg, the Czech (via Czechoslovakia), and the Slovenian lands (via Yugoslavia) regained their independence from German control. Germans in Eastern Europe were also expelled after the war.

The German question was a central aspect of the origins of the Cold War. The legal and diplomatic intercourse between the Allies regarding the treatment of the German question brought forward the elements of intervention and coexistence which formed the basis for a relatively peaceful postwar international order.[8] The division of Germany started with the creation of four occupation zones, continued with establishing two German states (West Germany and East Germany), was deepened in the period of Cold War with the Berlin Wall from 1961 and existed until 1989/1990. After the East German uprising of 1953, the official holiday in the Federal Republic of Germany was set on 17 June and was named "Day of German Unity", in order to remind all Germans of the “open” (unanswered) German Question (die offene Deutsche Frage), which meant the call for reunification.

Modern Germany's territory, after the reunification of East and West Germany in 1990, is closer to what the Kleindeutsche Lösung envisioned (aside from the fact that large areas of the former Prussia were no longer part of Germany) than the Großdeutsche Lösung, for Austria remains a separate country. Because of the idea's association with Nazism and rise of Austrian national identity, there are no mainstream political groups in Austria or Germany that advocate a "Greater Germany" today; those that do are often regarded as fascist and/or neo-Nazis.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Robert D. Billinger (1991). Metternich and the German Question: States' Rights and Federal Duties, 1820–1834. University of Delaware Press.

- ^ Blumenau, Bernhard (2018). "German foreign policy and the "German Problem" during and after the Cold War". In B Blumenau; J Hanhimäki; B Zanchetta (eds.). New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War. London: Routledge. pp. 92–116. doi:10.4324/9781315189031-6. ISBN 9781315189031.

- ^ "The Situation of Germany". (PDF) The New York Times, July 1, 1866.

- ^ Archives, The National (2019-09-09). "The National Archives - Milestones to peace: The Treaty of St. Germain-en-Laye". The National Archives blog. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ "Internet History Sourcebooks". sourcebooks.fordham.edu. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ Birgit Ryschka (2008). Constructing and Deconstructing National Identity: Dramatic Discourse in Tom Murphy's The Patriot Game and Felix Mitterer's In Der Löwengrube. Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631581117. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ "Bibliography: Anschluss". www.ushmm.org. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ Lewkowicz, Nicolas (2010). The German Question and the International Order, 1943-1948. New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-28332-9.