Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Lincoln | |

An early 14th-century portrait of Grosseteste[1] | |

| Installed | 1235 |

| Term ended | 1253 |

| Predecessor | Hugh of Wells |

| Successor | Henry of Lexington |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1168–70 |

| Died | 8 or 9 October 1253 (aged about 85) Buckden, Huntingdonshire Philosophy career |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Scholasticism |

Main interests | Theology, natural philosophy |

Notable ideas | Theory of scientific demonstration |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 9 October |

| Venerated in | Anglican Communion |

Robert Grosseteste[n 1] (/ˈɡroʊstɛst/ GROHS-test; Latin: Robertus Grosseteste; c. 1168-70 – 8 or 9 October 1253),[11] also known as Robert Greathead or Robert of Lincoln, was an English statesman, scholastic philosopher, theologian, scientist and Bishop of Lincoln. He was born of humble parents in Suffolk (according to the early 14th-century chronicler Nicholas Trevet), but the association with the village of Stradbroke is a post-medieval tradition.[12] Upon his death, he was revered as a saint in England, but attempts to procure a formal canonisation failed. A. C. Crombie called him "the real founder of the tradition of scientific thought in medieval Oxford, and in some ways, of the modern English intellectual tradition". As a theologian, however, he contributed to increasing hostility to Jews and Judaism, and spread the accusation that Jews had purposefully suppressed prophetic knowledge of the coming of Christ, through his translation of the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs.

Scholarly career

[edit]

There is very little direct evidence about Grosseteste's education. He may have received a liberal arts education at Lincoln and appears as a witness for the bishop of Lincoln in the late 1180s or early 1190s, where he is identified as a Master. From about 1195 he was active in the household of the Bishop of Hereford William de Vere; a letter from Gerald of Wales to William extolling Grosseteste's skills survives. Grosseteste appears not to have received any form of benefice from Bishop William, and on the latter's death in 1198, the household dissolved. There is no evidence that Grosseteste held any position in the households of William's successors, but it is possible that he was supported by Hugh Foliot, Archdeacon of Shropshire in the north of Hereford diocese. Grosseteste's movements are not clear in the next two decades or so, but he seems to have spent some time in France during the years of the interdict over England (1208–14), and acted as a papal judge-delegate, in company with Hugh Foliot, in or around 1216.

By 1225, he had gained the benefice of Abbotsley in the diocese of Lincoln, by which time he was a deacon. On that period in his life, scholarship is divided. Some historians argue that he began his teaching career in theology at Oxford in this year, whereas others have more recently argued that he used the income of his ecclesiastical post to support studies in theology at the University of Paris. However, there is clear evidence that by 1229/30 he was teaching at Oxford, but on the periphery as the lector in theology to the Franciscans, who had established a convent in Oxford about 1224. He remained in this post until March 1235.

Grosseteste may also have been appointed Chancellor of the University of Oxford. However, the evidence for this comes from a late thirteenth century anecdote whose main claim is that Grosseteste was in fact entitled the master of students (magister scholarium).

At the same time he began lecturing in theology at Oxford, Hugh of Wells, Bishop of Lincoln, appointed him as Archdeacon of Leicester,[14] and he also gained a prebend that made him a canon in Lincoln Cathedral. However, after a severe illness in 1232, he resigned all his benefices (Abbotsley and Leicester), but retained his prebend. His reasons were due to changing attitudes about the plurality of benefices (holding more than one ecclesiastical position simultaneously), and after seeking advice from the papal court, he tendered his resignations. The angry response of his friends and colleagues to his resignations took him by surprise and he complained to his sister and to his closest friend, the Franciscan Adam Marsh, that his intentions had been misunderstood.

As a master of the sacred page (manuscripts of theology in Latin), Grosseteste trained the Franciscans in the standard curriculum of university theology. The Franciscan Roger Bacon was his most famous disciple, and acquired an interest in the scientific method from him.[15] Grosseteste lectured on the Psalter, the Pauline epistles, Genesis (at least the creation account), and possibly on Isaiah, Daniel and Sirach. He also led disputations on such subjects as the theological nature of truth and the efficacy of the Mosaic Law. Grosseteste also preached at the university and appears to have been called to preach within the diocese as well. He collected some of those sermons, along with some short notes and reflections, not long after he left Oxford; this is now known as his Dicta. His theological writings reveal a continual interest in the natural world as a major resource for theological reflection and an ability to read Greek sources (if he ever learned Hebrew, it would be not until he became bishop of Lincoln). His theological index (tabula distinctionum) reveals the breadth of his learning and his desire to communicate it in a systematic manner.[16] However, Grosseteste's own style was far more unstructured than many of his scholastic contemporaries, and his writings reverberate with his own personal views and outlooks.

Bishop of Lincoln

[edit]

In February 1235, Hugh of Wells died, and the canons of Lincoln cathedral met to elect his successor. They soon were at a deadlock and could not reach a majority. Fearing that the election would be taken out of their hands, they settled on a compromise candidate, Grosseteste. He was consecrated in June of that same year[17] at Reading.[18] He instituted an innovative programme of visitation, a procedure normally reserved for the inspection of monasteries. Grosseteste expanded it to include all the deaneries in each archdeaconry of his vast diocese. The scheme brought him into conflict with more than one privileged corporation, in particular with his own chapter, who disputed his claim to exercise the right of visitation over their community. The dispute raged hotly from 1239 to 1245,[19] with the chapter launching an appeal to the papacy. In 1245, whilst attending the First Council of Lyon, the papal court ruled in favour of Grosseteste. Dean William de Thornaco is recorded as being suspended by Bishop Grosseteste in 1239, together with precentor and subdean in relation to the aforementioned matter.

In ecclesiastical politics the bishop belonged to the school of Thomas Becket. His zeal for reform led him to advance, on behalf of the courts, Christian claims which it was impossible that the secular power should admit. He twice incurred a rebuke from Henry III upon this subject although it was left for Edward I to settle the question of principle in favour of the state. The devotion of Grosseteste to the hierarchical theories of his age is attested by his correspondence with his chapter and the king. Against the former he upheld the prerogative of the bishops; against the latter he asserted that it was impossible for a bishop to disregard the commands of the Holy See. Where the liberties of the national church came into conflict with the assertions of Rome he stood by his own countrymen.[19]

Thus in 1238 he demanded that the King should release certain Oxford scholars who had assaulted the legate Otto Candidus. But at least up to the year 1247 he submitted patiently to papal encroachments, contenting himself with the protection (by a special papal privilege) of his own diocese from alien clerks. Of royal exactions he was more impatient; and, after the retirement of Archbishop (Saint) Edmund, constituted himself the spokesman of the clerical estate in the Great Council.[19]

In 1244 he sat on a committee which was empanelled to consider a demand for a subsidy. The committee rejected the demand, and Grosseteste foiled an attempt on the king's part to separate the clergy from the baronage. "It is written", the bishop said, "that united we stand and divided we fall."[19]

The last years of Grosseteste's life and episcopacy were embroiled in a conflict with the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Boniface of Savoy. In 1250, he travelled to the papal court, where one of the cardinals read his complaints at an audience with Innocent IV. He claimed not only that Boniface was threatening the health of the church but also that the pope was just as guilty for not reining him in and that that was symptomatic of the current malaise of the entire church. Most observers noted the personal animus between the bishop of Lincoln and the pope, but it did not stop the pope from agreeing to most of Grosseteste's demands about the way the English church ought to function.

Grosseteste continued to keep a watchful eye on ecclesiastical events. In 1251 he protested against a papal mandate enjoining the English clergy to pay Henry III one-tenth of their revenues for a crusade; and called attention to the fact that, under the system of provisions, a sum of 70,000 marks was annually drawn from England by the alien nominees of Rome. In 1253, upon being commanded to provide in his own diocese for a papal nephew, he wrote a letter of expostulation and refusal, not to the pope himself but to the commissioner, Master Innocent, through whom he received the mandate. The text of the remonstrance, as given in the Burton Annals and in Matthew Paris, has possibly been altered by a forger who had less respect than Grosseteste for the papacy. The language is more violent than that which the bishop elsewhere employs. But the general argument, that the papacy may command obedience only so far as its commands are consonant with the teaching of Christ and the apostles, is only what should be expected from an ecclesiastical reformer of Grosseteste's time. There is much more reason for suspecting the letter addressed "to the nobles of England, the citizens of London, and the community of the whole realm", in which Grosseteste is represented as denouncing in unmeasured terms papal finance in all its branches. But even in this case allowance must be made for the difference between modern and medieval standards of decorum.[19]

Grosseteste numbered among his most intimate friends the Franciscan teacher, Adam Marsh. Through Adam he came into close relations with Simon de Montfort. From the Franciscan's letters it appears that the earl had studied a political tract by Grosseteste on the difference between a monarchy and a tyranny and that he embraced with enthusiasm the bishop's projects of ecclesiastical reform. Their alliance began as early as 1239, when Grosseteste exerted himself to bring about a reconciliation between the king and the earl. But there is no reason to suppose that the political ideas of Montfort had matured before the death of Grosseteste; nor did Grosseteste busy himself overmuch with secular politics, except insofar as they touched the interest of the Church. Grosseteste realised that the misrule of Henry III and his unprincipled compact with the papacy largely accounted for the degeneracy of the English hierarchy and the laxity of ecclesiastical discipline. But he can hardly be termed a constitutionalist.[19]

Hostility to Jews and Judaism

[edit]Grosseteste has a mixed reputation among scholars regarding his attitudes to Jews and Judaism. He was certainly hostile to usury, but had an interest in the relationship between the Old Law and the New. He intervened when Simon de Montfort expelled the Jews of Leicester, but his views on the expulsion itself are unclear.[20]

He appears to have become more hostile to Jews in his later life, and this can be traced through his theological investigations. Earlier in his life, while lecturing in Oxford, he analysed the Psalms and Paul's Letter to the Galatians. He concluded that the Jews are wedded to the past and their lineage, rather than a search for salvation, following the work of Chrysostom.[21] In his analysis of Galatians and De cessatione legalium, citing Jerome he sets out his understanding of the status of the Old Law, and concludes that it had been "made void" by the resurrection of Christ, and that the Jewish faith was therefore heretical and blasphemous.[22] He followed the view of Augustine and Innocent III, who had reiterated these in recent Papal Bulls that the Jews were guilty for death of Christ, but just as Cain, who had killed Abel, was allowed to live as punishment, so Jews were to live in exile and servitude as punishment for their sin. Jews were not to be allowed to live in luxury from the proceeds of usury, and any Christian ruler allowing or the "oppression" of Christians through usury would be share the Jews' punishment in the next life.[23] Nevertheless, as Bishop, he seems to have taken few practical actions against Jews, in contrast, for example to his associate Walter de Cantilupe. One concrete example can be found in the mid 1240s, where in a letter to his archdeacons, he warns them among many other matters, that they were ensure that Christians and Jews do not associate.[24]

In 1242, Grosseteste translated the Greek text Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs into Latin. It was among his most influential works, being cited by Vincent de Beauvais, Bonaventure and Roger Bacon. The book describes the dying words of Jacob's sons, in which they foretell the coming of Christ as the Messiah. The text appeared to prove that Jews had been told of the Messiah, and had written the prophecies down, but had then deliberately ignored and suppressed them. Matthew Paris for instance made this interpretation explicit, saying Grosseteste had exposed the deceit of the Jews to their "great confusion".[25]

Grosseteste began to study Hebrew as well as Greek, and although he may have lacked proficiency, spent considerable effort attempting to better understand the Psalms in their original language. His goal was to eliminate conflict between Christians and Jews, or to "confirm the faithful and convert the infidel".[26] The evolution of Grosseteste's views from the Augustinian view of Jewish ignorance and punishment to one where Jews appeared to be stubbornly and knowingly rejecting Christ, was part of a wider shift that was taking place, leading to greater suspicion and intolerance.[26]

Science

[edit]Grosseteste is best known as an original thinker for his work concerning what would today be called science or the scientific method.

It has been argued that Grosseteste played a key role in the development of the scientific method. Grosseteste did introduce to the Latin West the notion of controlled experiment and related it to demonstrative science, as one among many ways of arriving at such knowledge.[27] Although Grosseteste did not always follow his own advice during his investigations, his work is seen as instrumental in the history of the development of the Western scientific tradition.

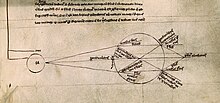

Grosseteste was the first of the Scholastics to fully understand Aristotle's vision of the dual path of scientific reasoning: generalising from particular observations into a universal law, and then back again from universal laws to prediction of particulars. Therefore, scientific knowledge was demonstrative knowledge of things through their causes.[28] Grosseteste called this "resolution and composition". So, for example, looking at the particulars of the moon, it is possible to arrive at universal laws about nature. Conversely once these universal laws are understood, it is possible to make predictions and observations about other objects besides the moon. Grosseteste said further that both paths should be verified through experimentation to verify the principles involved. These ideas established a tradition that carried forward to Padua and Galileo Galilei in the 17th century.

As important as "resolution and composition" would become to the future of Western scientific tradition, more important to his own time was his idea of the subordination of the sciences. For example, when looking at geometry and optics, optics is subordinate to geometry because optics depends on geometry, and so optics was a prime example of a subalternate science. Thus Grosseteste concluded, following much of what Boethius had argued, that mathematics was the highest of all sciences, and the basis for all others, since every natural science ultimately depended on mathematics. He supported this conclusion by looking at light, which he believed to be the "first form" of all things, the source of all generation and motion (approximately what is now known as biology and physics). Hence, since light could be reduced to lines and points, and thus fully explained in the realm of mathematics, mathematics was the highest order of the sciences.

Grosseteste had read several important works translated from Greek via Arabic, including De Speculis by Euclid (and likely also De Visu), Meteorologica and De Generatione Animalium by Aristotle, and directly from Arabic, such as Liber Canonis by Avicenna. He likely also read al-Kindi's De Aspectibus.[29] Drawing on these sources, Grosseteste produced important work in optics, which would be continued by Roger Bacon, who often mentioned his indebtedness to him although there is no proof that the two ever met. In De Iride Grosseteste writes:

This part of optics, when well understood, shows us how we may make things a very long distance off appear as if placed very close, and large near things appear very small, and how we may make small things placed at a distance appear any size we want, so that it may be possible for us to read the smallest letters at incredible distances, or to count sand, or seed, or any sort of minute objects.

Editions of the original Latin text may be found in: Die Philosophischen Werke des Robert Grosseteste, Bischofs von Lincoln (Münster i. W., Aschendorff, 1912.), p. 75.[30]

Grosseteste is now believed to have had a very modern understanding of light and colour, which is shown by his scientific treatises De Luce (On Light) and De Colore (On Colour). De Luce explores the nature of light, matter, and the cosmos. He argued that light is an infinitely small particle which was the first form of everything within the universe that multiplied itself indefinitely that resulted in a finite magnitude which was physical matter. Grosseteste described the birth of the Universe in an explosion and the crystallisation of light into matter to form stars and planets in a set of nested spheres around Earth. He also came to the conclusion that, as light dragged the matter of the universe outward and expanded the universe, the density must decrease as the radius increases. Thus, invoking a conservation law centuries before conservation laws became fundamental in modern science.[31] De Luce is the first attempt to describe the heavens and Earth using a single set of physical laws, four centuries before Isaac Newton proposed gravity and seven centuries before the Big Bang theory. In his treatise, De Colore, Robert Grosseteste had defined colour as light incorporated in a diaphanous material. Meaning that colour is associated with the interaction of light and materials and that it is a product of variations in the qualities of both the light and the medium. De Colore was Grosseteste's replacement of Aristotle's linear colour arrangement between black and white to a three dimensional one based on the aforementioned aspects with 7 different directions of colour from white to black with infinite variations in intensity.[32]

The 'Ordered Universe' collaboration of scientists and historians at Durham University studying medieval science regard him as a key figure in showing that pre-Renaissance science was far more advanced than previously thought.

Supposed errors in his account have been found to be based on corrupt late copies of his essay on the nature of light, written in about 1225 (De Luce). In 2014 Grosseteste's 1225 treatise De Luce was translated from Latin and interpreted by an interdisciplinary project led by Durham University, that included Latinists, philologists, medieval historians, physicists and cosmologists.

Literary and poetic works

[edit]Grosseteste wrote a number of early works in Latin and French whilst he was a clerk, including one called Chateau d'amour, an allegorical poem on the creation of the world and Christian redemption, as well as several other poems and texts on household management and courtly etiquette. He also wrote a number of theological works including the influential Hexaëmeron in the 1230s. He was also a highly regarded author of manuals on pastoral care and produced treatises that dealt with a variety of penitential contexts, including monasteries, the parish and a bishop's household.

In 1242, having been introduced to the Greek work by John of Basingstoke, Grosseteste had the Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs brought from Greece and translated it with help of a clerk of St Albans:

for the strengthening of the christian [sic] faith and the confusion of the Jews [who were said to have deliberately hidden the book away] ... on account of the manifest prophecies of Christ contained therein.[33]

He also wrote a number of commentaries on Aristotle, including the first in the West of Posterior Analytics, and one on Aristotle's Physics, which has survived as a loose collection of notes or glosses on the text. Moreover, he did a lot of very interesting work on Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite's Celestial Hierarchy: he translated both the text and the scholia from Greek into Latin and wrote a commentary.[34]

Death and burial

[edit]Grosseteste died on 9 October 1253.[17][35] He was aged about 80–85.

He is buried in a tomb within his memorial chapel within Lincoln Cathedral. Its dedicatory plaque reads as follows:

In this place lies the body of ROBERT GROSSETESTE who was born at Stradbroke in Suffolk, studied in the University of Paris – and in 1224 became the Chancellor of Oxford University where he befriended and taught the newly founded orders of Friars : In 1229 he became Archdeacon of Leicester and a Canon of this Cathedral – reigning as Bishop of Lincoln from 17th. June 1235 until his death.

He was a man of learning and an inspiration to scholars a wise administrator whilst a true shepherd of his flock, ever concerned to lead them to Christ in whose service he strove to temper justice with mercy, hating the sin while loving the sinner, not sparing the rod though cherishing the weak – He died on 8 October 1253.

After his death, an anecdote of Pope Innocent's death by Matthew Paris, is often mentioned well into the 16th century to the effect that the ghost of Grosseteste visited the Pope in the night and gave him a blow to the heart which killed.[36]

Veneration

[edit]Upon his death, he was almost universally revered as a saint in England, with miracles reported at his shrine and pilgrims to it granted an indulgence by the bishop of Lincoln.[37] However, attempts by successive Bishops of Lincoln, the University of Oxford, and Edward I to secure a formal papal canonisation failed.[37] The attempts to have him canonised were unsuccessful because of his opposition to Pope Innocent IV. The reason for this also seems to be because it was rumoured that Grosseteste's ghost was responsible for the death of the Pope.[36]

In most of the modern Anglican Communion, Robert Grosseteste is considered beatified and commemorated on 9 October.[38] Grosseteste is honoured in the Church of England and in the Episcopal Church on 9 October.[39][40]

Reputation and legacy

[edit]Grosseteste was already an elderly man, with an established reputation, when he became a bishop. As an ecclesiastical statesman, he showed the same fiery zeal and versatility of which he had given proof in his academic career; but the general tendency of modern writers has been to exaggerate his political and ecclesiastical services, and to neglect his performance as a scientist, an astrologer, and scholar. The opinion of his own age, as expressed by Matthew Paris and Roger Bacon, was very different. His contemporaries, while admitting the excellence of his intentions as a statesman, lay stress upon his defects of temper and discretion. Grosseteste was known to be somewhat critical towards everyone, and was known to often express his opinions regardless of status. Some of these conflicts involve the King, Abbot of Westminster and Pope Innocent. His morals were high and he recognised that even those of the church could be corrupt and worked to fight against that corruption.[36] But they see in him the pioneer of a literary and scientific movement; not merely a great ecclesiastic who patronised learning in his leisure hours, but the first mathematician and physicist of his age. He anticipated, in these fields of thought, some of the striking ideas to which Roger Bacon subsequently gave a wider currency.[19]

Bishop Grosseteste University in Lincoln is named after Robert Grosseteste. The university provides Initial Teacher Training and academic degrees at all levels. In 2003, it hosted an international conference on Grosseteste in honour of the 750th anniversary of his death.

Grosseteste has been recognised in many ways for his knowledge and contributions to the sciences. He was entered under the section "Scholars and Divines" in John Evelyn's Numismata: A discourse of Medals, entered under the name "Grosthed" listed among others that Evelyn describes as "famous and illustrious".[36][41] In 2014, The Robert Grosseteste Society has called for a statue to be erected so that he may be recognised for his achievements.[42]

Works

[edit]Scientific treaties

[edit]From about 1220 to 1235 he wrote a host of scientific treatises including:

- De sphera. An introductory text on astronomy.

- De luce. On the "metaphysics of light." (which is the most original work of cosmogony in the Latin West)

- De accessu et recessu maris. On tides and tidal movements. (although some scholars dispute his authorship)

- De lineis, angulis et figuris. Mathematical reasoning in the natural sciences.

- De phisicis lineis, angulis et figuris (in Latin). Nürnberg. 1503.

- De iride. On the rainbow.

- De colore. On colour.

Editions

[edit]- Versio Caelestis Hierarchiae Pseudo-Dionysii Areopagitae cum scholiis ex Graeco sumptis necnon commentariis notulisque eiusdem Lincolniensis, ed. D. A. Lawell (Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Mediaevalis 268), Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2015 (ISBN 978-2-503-55593-5)

- Opera I. Expositio in Epistolam sancti Pauli ad Galatas. Glossarum in sancti Pauli Epistolas fragmenta. Tabula, ed. J. McEvoy, L. Rizzerio, R.C. Dales, P.W. Rosemann (Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Mediaevalis 130), Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 1995 (ISBN 978-2-503-04301-2)

- The Greek Commentaries of the Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle in the Latin Translation of Robert Grosseteste, ed. H Mercken (Corpus Latinum Commentariorum in Aristotelem Graecorum VI), Leiden: Brill, 1973–1991

- On Light, ed. C Riedl, (Milwaukee, WI, 1942)

Works in translation

[edit]- Mystical theology: The Glosses by Thomas Gallus and the Commentary of Robert Grosseteste on De mystica theologia , ed. J McEvoy, (Paris: Peeters, 2003)

- On the Six Days of Creation, tr. CFJ Martin, (Oxford, 1996)

See also

[edit]- Brazen head

- Greyfriars, Oxford

- History of science in the Middle Ages

- History of the scientific method

- List of bishops of Lincoln and precursor offices

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- Oxford Franciscan school

Notes

[edit]- ^ The name is the Norman French form of Robert Greathead (Latin: Robertus Capito, Capitus, Megacephalus, or Grossum Caput) or the gallicised Robert Grosstête (/ˈɡroʊsteɪt/ GROHS-tayt; Latin: Robertus Grossetesta or Grossatesta).[8] Also known as Robert of Lincoln (Latin: Robertus Lincolniensis, Linconiensis, &c.) or Rupert of Lincoln (Latin: Rubertus Lincolniensis, &c.).[9][10]

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Archer, Thomas Andrew (1885). "Basing, John". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Archer, Thomas Andrew (1885). "Basing, John". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

References

[edit]- ^ Brev. Hist. Ang. Scot. &c. (Harleian MS 3860, f. 48).

- ^ Richard of Bardney in his work 'The Life of Robert Grosstête' gives Stow as Grosseteste's birthplace, without mentioning Suffolk. R. W. Southern (1986, p. 77) notes that there are three Stows in Suffolk.

- ^ Steven P. Marrone, William of Auvergne and Robert Grosseteste: New Ideas of Truth in Early Thirteenth Century, Princeton University Press, 2014, p. 146.

- ^ Charles Edwin Butterworth, Blake Andrée Kessel (eds.), The Introduction of Arabic Philosophy Into Europe, BRILL, 1994, p. 55.

- ^ Hackett, Jeremiah M.G. (1997), "Roger Bacon: His Life, Career, and Works", Roger Bacon and the Sciences: Commemorative Essays, Studien und Texte zur Geistesgeschichte des Mittelalters, No. 57, Leiden: Brill, p. 10, ISBN 90-04-10015-6

- ^ Edith Wilks Dolnikowski, Thomas Bradwardine: A View of Time and a Vision of Eternity in Fourteenth Century Thought, BRILL, 1995, p. 101 n. 4.

- ^ Tom Sorell (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Hobbes, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 155 n. 93.

- ^ G.M. Miller, BBC Pronouncing Dictionary of British Names (London: Oxford UP, 1971), p. 65.

- ^ "Grosseteste, Robert (1168–1253)", CERL Thesaurus.

- ^ Grosseteste, Robert 1175?–1253", OCLC WorldCat Identities.

- ^ Lewis 2019 has 1168, Southern 2010 has 1170

- ^ Giles E. M. Gasper, et al, Knowing and Speaking: Robert Grosseteste's "De artibus liberalibus" ("On the Liberal Arts") and "De Generatione Sonorum" ("On the Generation of Sounds)" (Oxford University Press, 2019), pp. 9–35 and 199–225.

- ^ Grosseteste, Dicta CXLVII &c. (Royal 6 E p. 116).

- ^ British History Online Archdeacons of Leicester accessed on 28 October 2007

- ^ John Freely, Aladdin's Lamp: How Greek Science Came to Europe Through the Islamic World, Alfred A. Knopf, 2009

- ^ Dabhoiwala, Fara (22 June 2023). "Life Is Short. Indexes Are Necessary". New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ a b Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 255

- ^ British History Online Bishops of Lincoln accessed on 28 October 2007

- ^ a b c d e f g One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Davis, Henry William Carless (1911). "Grosseteste, Robert". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 617.

- ^ Tolan 2023, p. 104.

- ^ Tolan 2023, pp. 106–7.

- ^ Tolan 2023, pp. 106–109.

- ^ Tolan 2023, p. 109.

- ^ Tolan 2023, p. 110.

- ^ Tolan 2023, pp. 112–3.

- ^ a b Tolan 2023, pp. 113–4.

- ^ Neil, Lewis. "Robert Grosseteste". plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Cunningham, Jack P. (2016), "Robert Grosseteste and the Pursuit of Learning in the Thirteenth Century", Robert Grosseteste and the pursuit of Religious and Scientific Learning in the Middle Ages, Studies in the History of Philosophy of Mind, vol. 18, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 41–57, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-33468-4_3, ISBN 978-3-319-33466-0, retrieved 1 December 2022

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (1976). Theories of Vision from al-Kindi to Kepler. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 94.

- ^ A reproduction of this text may be found on the website: The Electronic Grossteste Archived 2 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine – online Archived 27 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cunningham, Jack P. (2016). Robert Grosseteste and the pursuit of Religious and Scientific Learning in the Middle Ages. Mark Hocknull. pp. 7–11. ISBN 978-3-319-33466-0.

- ^ Cunningham, Jack P. (2016), "Robert Grosseteste and the Pursuit of Learning in the Thirteenth Century", Robert Grosseteste and the pursuit of Religious and Scientific Learning in the Middle Ages, Studies in the History of Philosophy of Mind, vol. 18, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 61–83, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-33468-4_3, ISBN 978-3-319-33466-0, retrieved 28 October 2022

- ^ Archer 1885.

- ^ See the edition by D. A. Lawell, Versio Caelestis Hierarchiae Pseudo-Dionysii Areopagitae cum scholiis ex Graeco sumptis necnon commentariis notulisque eiusdem Lincolniensis (= Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Mediaevalis 268), Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2015 (ISBN 978-2-503-55593-5).

- ^ James McEvoy, Robert Grosseteste (Oxford University Press 2000 ISBN 978-0-19535417-1), p. 30

- ^ a b c d International Robert Grosseteste Society. Conference (2013). Robert Grosseteste and his intellectual milieu: new editions and studies. Robert Grosseteste, Joseph Goering, James R. Ginther, John Flood, Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. ISBN 978-0-88844-824-8. OCLC 828234083.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Cath. Enc. (1910).

- ^ ASB (1991).

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 17 December 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4.

- ^ Evelyn, John (1697). Numismata: A discourse of Medals: Together with some Account of Heads and Effigies of Illustrious, and Famous Persons, in Sculps, and Taille-Douce, of Whom we have no Medals extant, and of the Use to be derived from them : to which is added A Digression concerning Physiognomy. Tooke.

- ^ Flood, John (21 July 2014). "Grosseteste Statue". International Robert Grosseteste Society. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Baur L. (ed.) Die Philosophischen Werke des Robert Grosseteste, Bischofs von Lincoln in Baeumker's Beiträge zur Geschichte der Philosophie des Mittelalters series, vol. IX (Münster i. W.: Aschendorff, 1912).

- Crombie, A. C. Robert Grosseteste and the Origins of Experimental Science. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971, OCLC 401196. ISBN 0-19-824189-5 (1953).

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Ginther, James R. Master of the Sacred Page: A Study of the Theology of Robert Grosseteste (ca. 1229/30-1235). Aldershot: Ashgate Publishers, 2004. ISBN 0-7546-1649-5.

- Goering, J. W. & Mackie, E. A. (eds.), Editing Robert Grosseteste, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003. ISBN 978-080-208-841-3

- Lewis, Neil (2019), "Robert Grosseteste", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Luard, Henry Richards (1890). . In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney (eds.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 23. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- McEvoy, James. The Philosophy of Robert Grosseteste. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-824645-5.

- McEvoy, James. Robert Grosseteste. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Southern, R. W. (2010). "Grosseteste, Robert". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11665. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Southern, R. W. Robert Grosseteste: The Growth of an English Mind in Medieval Europe. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986. ISBN 0-19-820310-1 (Oxford University Press, US; 2 edition (1 February 1992) pbk)

- Tolan, John (2023). England's Jews: Finance, Violence, and the Crown in the Thirteenth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-1512823899. OL 39646815M.

External links

[edit]- International Robert Grosseteste Society

- Ordered Universe Project

- "Robert Grosseteste", The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. VII, New York: Robert Appleton Co., 1910.

- "Robert Grosseteste". In Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Clare Riedl's 1942 translation of On Light

- Medieval bishop's theory resembles modern concept of multiple universes (24 April 2014 by Tom Mcleish, Giles Gasper And Hannah Smithson, The Conversation)

- McLeish, Tom; Gasper, Giles; Smithson, Hannah (7 June 2015). "Our latest scientific research partner was a medieval bishop". The Conversation US. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- Brookes, Michael (27 November 2014). "The medieval bishop who helped to unweave the rainbow". The Guardian.

- "October", The Anglican Service Book, Rosemont: Good Shepherd Press, reprinted 2007, 1991, p. 24, ISBN 9780962995507.

- British History Online Archdeacons of Leicester accessed on 28 October 2007.

- British History Online Bishops of Lincoln accessed on 28 October 2007.

- 230. A Light That Never Goes Out: Robert Grosseteste Episode of History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps by Peter Adamson (28 June 2015).

- 1168 births

- 1253 deaths

- 13th-century English Roman Catholic theologians

- 13th-century philosophers

- Catholic philosophers

- Scholastic philosophers

- People from Stradbroke

- 13th-century English scientists

- English philosophers

- English Franciscans

- Philosophers of science

- Catholic clergy scientists

- Bishops of Lincoln

- Archdeacons of Leicester

- Clerks

- Academics of the University of Oxford

- Chancellors of the University of Oxford

- Burials in Lincolnshire

- 13th-century English Roman Catholic bishops

- 13th-century writers in Latin

- Greek–Latin translators

- 13th-century astronomers

- 13th-century English mathematicians

- 13th-century translators

- Medieval English astronomers

- Medieval physicists

- Anglican saints

- Burials at Lincoln Cathedral