NASA Pathfinder

| Pathfinder Pathfinder Plus | |

|---|---|

Pathfinder in flight over Hawaii | |

| General information | |

| Type | Remote controlled UAV |

| Manufacturer | AeroVironment |

| Primary user | NASA ERAST Program |

| Number built | 1 |

| History | |

| Developed into | NASA Centurion NASA Helios |

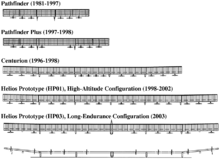

The NASA Pathfinder and NASA Pathfinder Plus were the first two aircraft developed as part of an evolutionary series of solar- and fuel-cell-system-powered unmanned aerial vehicles. AeroVironment, Inc. developed the vehicles under NASA's Environmental Research Aircraft and Sensor Technology (ERAST) program. They were built to develop the technologies that would allow long-term, high-altitude aircraft to serve as atmospheric satellites, to perform atmospheric research tasks as well as serve as communications platforms.[1] They were developed further into the NASA Centurion and NASA Helios aircraft.

Pathfinder

[edit]AeroVironment initiated its development of full-scale solar-powered aircraft with the Gossamer Penguin and Solar Challenger vehicles in the late 1970s and early 1980s, following the pioneering work of Robert Boucher, who built the first solar-powered flying models in 1974. As part of the ERAST program, AeroVironment built four generations of long endurance unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) under the leadership of Ray Morgan, the first of which was the Pathfinder.

Development

[edit]In 1983, AeroVironment obtained funding from an unspecified US government agency to secretly investigate a UAV concept designated "High Altitude Solar" or HALSOL. The HALSOL prototype first flew in June 1983. Nine HALSOL flights took place at Groom Lake in Nevada. The flights were conducted using radio control and battery power, as the aircraft had not been fitted with solar cells. HALSOL's aerodynamics were validated, but the investigation led to the conclusion that neither photovoltaic cell nor energy storage technology were mature enough to make the idea practical for the time being, and so HALSOL was put into storage.[2]

In 1993, after ten years in storage, the aircraft was brought back to flight status for a brief mission by the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization (BMDO). With the addition of small solar arrays, five low-altitude checkout flights were flown under the BMDO program at NASA Dryden in the fall of 1993 and early 1994 on a combination of solar and battery power.[3]

In 1994 the aircraft transferred to the NASA ERAST Program to develop science platform aircraft technology. It was renamed "Pathfinder" because it was "literally the pathfinder for a future fleet of solar-powered aircraft that could stay airborne for weeks or months on scientific sampling and imaging missions".[3] A series of flights were planned to demonstrate that an extremely light and fragile aircraft structure with a very high aspect ratio (the ratio between the wingspan and the wing chord) can successfully take-off and land from an airport and can be flown to extremely high altitudes (between 50,000 feet (15,000 m) and 80,000 feet (24,000 m)) propelled by the power of the sun. In addition, the ERAST Project also wanted to determine the feasibility of such a UAV for carrying instruments used in a variety of scientific studies.[4]

On October 21, 1995, the aircraft's fragility was aptly demonstrated when it was severely damaged in a hangar accident, but was subsequently rebuilt.[4]

Aircraft description

[edit]Pathfinder was powered by eight electric motors — later reduced to six — which were first powered by batteries. It had a wing span of 98.4 feet (30.0 m). Two underwing pods contain the landing gear, batteries, triple-redundant instrumentation system, and dual-redundant flight control computers. By the time the aircraft was adopted into the ERAST project in late 1993, solar cells were being added, eventually covering the entire upper surface of the wing.[1] The solar arrays provide power for the aircraft's electric motors, avionics, communications and other electronic systems. Pathfinder also had a backup battery system that can provide power for between two and five hours to allow limited-duration flight after dark.[3]

Pathfinder flies at an airspeed of only 15 miles per hour (24 km/h) to 25 miles per hour (40 km/h). Pitch control is maintained by the use of tiny elevators on the trailing edge of the wing Turn and yaw control is accomplished by slowing down or speeding up the motors on the outboard sections of the wing.[3]

Flight testing and records

[edit]Major science activities of Pathfinder missions have included detection of forest nutrient status, forest regrowth after damage caused by Hurricane Iniki in 1992, sediment/algal concentrations in coastal waters and assessment of coral reef health. Science activities are coordinated by the NASA Ames Research Center and include researchers at the University of Hawaii and the University of California. Pathfinder flight tested two ERAST-developed scientific instruments, a high spectral resolution Digital Array Scanned Interferometer (DASI) and a high spatial resolution Airborne Real-Time Imaging System (ARTIS), both developed at Ames. These flights were conducted at altitudes between 22,000 feet (6,700 m) and 49,000 feet (15,000 m) in 1997.[3]

On September 11, 1995, Pathfinder set an unofficial altitude record for solar powered aircraft of 50,000 feet (15,000 m) during a 12-hour flight from NASA Dryden.[1][4] This and subsequent records claimed by NASA for Pathfinder remain unofficial, as they were not validated by the FAI, the internationally recognized aviation world record sanctioning body. The National Aeronautic Association presented the NASA-industry ERAST team with an award for one of the "10 Most Memorable Record Flights" of 1995.[3]

After further modifications, the aircraft was moved to the U.S. Navy's Pacific Missile Range Facility (PMRF) on the Hawaiian island of Kauai. On one of seven flights there in the spring and summer of 1997, Pathfinder raised the altitude record for solar-powered aircraft — as well as propeller-driven aircraft — to 71,530 feet (21,800 m) on July 7, 1997. During those flights, Pathfinder carried two lightweight imaging instruments to learn more about the island's terrestrial and coastal ecosystems, demonstrating the potential of such aircraft as platforms for scientific research.[1]

Pathfinder-Plus

[edit]

During 1998, the Pathfinder was modified into the longer-winged Pathfinder-Plus configuration. It used four of the five sections from the original Pathfinder wing, but substituted a new 44 feet (13 m) long center wing section that incorporated a high-altitude airfoil designed for the follow-on Centurion/Helios. The new section was twice as long as the original, and increased the overall wingspan of the craft from 98.4 feet (30.0 m) to 121 feet (37 m). The new center section was topped by more-efficient silicon solar cells developed by SunPower Corporation of Sunnyvale, California, which could convert almost 19 percent of the solar energy they receive to useful electrical energy to power the craft's motors, avionics and communication systems. That compared with about 14 percent efficiency for the older solar arrays that cover most of the surface of the mid- and outer wing panels from the original Pathfinder. Maximum potential power was boosted from about 7,500 watts on Pathfinder to about 12,500 watts on Pathfinder-Plus. The number of electric motors was increased to eight, and the motors used were more powerful units, designed for the follow-on aircraft.[3]

The Pathfinder-Plus development flights flown at PMRF in the summer of 1998 validated power, aerodynamic, and systems technologies for its successor, the Centurion. On August 6, 1998, Pathfinder-Plus, piloted by Derek Lisoski, proved its design by raising the national altitude record to 80,201 feet (24,445 m) for solar-powered and propeller-driven aircraft.[1][5]

Atmospheric satellite tests

[edit]In July 2002 Pathfinder-Plus carried commercial communications relay equipment developed by Skytower, Inc., a subsidiary of AeroVironment, in a test of using the aircraft as a broadcast platform. Skytower, in partnership with NASA and the Japan Ministry of Telecommunications, tested the concept of an "atmospheric satellite" by successfully using the aircraft to transmit both an HDTV signal as well as an IMT-2000 wireless communications signal from 65,000 feet (20,000 m), giving the aircraft the equivalence of a 12 miles (19 km) tall transmitter tower. Because of the aircraft's high lookdown angle, the transmission utilized only one watt of power, or 1/10,000 of the power required by a terrestrial tower to provide the same signal.[6] According to Stuart Hindle, Vice President of Strategy & Business Development for SkyTower, "SkyTower platforms are basically geostationary satellites without the time delay." Further, Hindle said that such platforms flying in the stratosphere, as opposed to actual satellites, can achieve much higher levels of frequency use. "A single SkyTower platform can provide over 1,000 times the fixed broadband local access capacity of a geostationary satellite using the same frequency band, on a bytes per second per square mile basis."[7]

Ray Morgan, president of AeroVironment, has described the concept as, "What we're trying to do is create what we call an 'atmospheric satellite,' which operates and performs many of the functions as a satellite would do in space, but does it very close in, in the atmosphere"[8]

Specifications

[edit]

| Pathfinder | Pathfinder-Plus | Centurion | Helios HP01 | Helios HP03 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length ft(m) | 12 (3.6) | 12 (3.6) | 12 (3.6) | 12 (3.6) | 16.5 (5.0) |

| Chord ft(m) | 8 (2.4) | ||||

| Wingspan ft(m) | 98.4 (29.5) | 121 (36.3) | 206 (61.8) | 247 (75.3) | |

| Aspect ratio | 12 to 1 | 15 to 1 | 26 to 1 | 30.9 to 1 | |

| Glide ratio | 18 to 1 | 21 to 1 | ? | ? | ? |

| Airspeed kts(km/h) | 15–18 (27–33) | 16.5–23.5 (30.6–43.5) | ? | ||

| Max altitude ft(m) | 71,530 (21,802) | 80,201 (24,445) | n/a | 96,863 (29,523) | 65,000 (19,812) |

| Empty Wt lb(kg) | ? | ? | ? | 1,322 (600) | ? |

| Max. weight lb(kg) | 560 (252) | 700 (315) | ±1,900 (±862) | 2,048 (929) | 2,320 (1,052) |

| Payload lb(kg) | 100 (45) | 150 (67,5) | 100–600 (45–270) | 726 (329) | ? |

| Engines | electric, 2 hp (1.5 kW) each | ||||

| No. of engines | 6 | 8 | 14 | 14 | 10 |

| Solar pwr output (kW) | 7.5 | 12.5 | 31 | 35 | 18.5 |

| Supplemental power | batteries | batteries | batteries | Li batteries | Li batteries, fuel cell |

See also

[edit]- Electric aircraft

- History of unmanned aerial vehicles

- Regenerative fuel cell

- NASA Centurion (First flight 10 November 1998)

- NASA/AeroVironment Helios Prototype (First flight 8 September 1999)

- QinetiQ/Airbus Zephyr (First flight in 2008)

- Facebook Aquila (First flight 28 June 2016)

- SoftBank/AeroVironment HAPSMobile (First flight 11 September 2019)

- BAE Systems PHASA-35 (First flight 17 February 2020)

References

[edit]This article contains material that originally came from the web article "Unmanned Aerial Vehicles" by Greg Goebel, which exists in the Public Domain.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ^ a b c d e f "NASA Armstrong Fact Sheet: Helios Prototype". NASA. 13 August 2015. Archived from the original on 2023-04-19.

- ^ Goebel, Greg, "The Prehistory of Endurance UAVs", Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, chapter 12. Exists in the public domain. Archived 2009-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h NASA Pathfinder fact sheet, archived at archive.org

- ^ a b c NASA Pathfinder fact sheet, archived at archive.org

- ^ NAA record database Archived 2012-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "SkyTower Successfully Tests World's First Commercial Telecom Applications from More Than 65,000 feet (20,000 m) in the Stratosphere", Ewire, July 22, 2002, accessed September 11, 2008 Archived November 20, 2006, at archive.today

- ^ David, Leonard, "Stratospheric Platform Serves As Satellite" Space.com, July 24, 2002, accessed September 11, 2008 Archived May 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Knapp, Don. "'Atmospheric satellites' could cut the cost of communications", CNN, August 11, 1998, accessed September 13, 2008

- ^ Investigation of the Helios Prototype Aircraft Mishap – Volume 1, T.E. Noll et al., January 2004

- ^ NASA Centurion Fact Sheet archived at archive.org

- ^ NASA.gov

- "Photovoltaic Finesse: Better Solar Cells—with Wires Where the Sun Don't Shine", an article by Daniel Cho on page thirty-three of the September, 2003 issue of Scientific American

External links

[edit]- NASA's Helios Project

- Helios for kids

- Helios model by DesignsbyALX Archived 2011-05-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- "3G Tested at 65,000 feet (20,000 m) in the stratosphere" 3G news release July 23, 2002

- Science Daily article on Pathfinder Plus altitude record

- Telecom relay achievements at Airport International

- Space.com article

- History of solar powered UAVs at The Future of Things

- Pathfinder Plus at NASM

- NASA-AeroVironment contract for followon projects[permanent dead link]

- Helios record attempt article

- NASA image collections: