HMCS CH-14

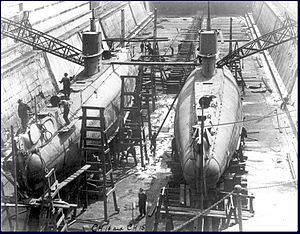

CH-14 (left) and CH-15 (right) in drydock.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | H14 |

| Ordered | December 1914 |

| Launched | 3 July 1915 |

| Fate | transferred to Canada 1919 |

| Name | CH-14 |

| Acquired | June 1919 |

| Commissioned | 1 April 1921 |

| Decommissioned | 30 June 1922 |

| Fate | Scrapped in 1927 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | H-class submarine |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 45.8 m (150 ft 3 in) o/a |

| Beam | 4.6 m (15 ft 1 in) |

| Draught | 3.68 m (12 ft 1 in) |

| Propulsion | |

| Speed |

|

| Range | 1,600 nmi (3,000 km; 1,800 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph) surfaced |

| Endurance | 16 long tons (16 t) of diesel fuel |

| Test depth | 200 m (660 ft) |

| Complement | 22 |

| Armament |

|

HMCS CH-14 was an H-class submarine originally ordered for the Royal Navy as H14 during the First World War. Constructed in the United States during their neutrality, the submarine was withheld from the Royal Navy until after the US entry into the war. Entering service at the very end of the war, the submarine saw no action and was laid up at Bermuda following the cessation of hostilities. The submarine was gifted to Canada in 1919 and was in service with the Royal Canadian Navy from 1921 to 1922 as CH-14. The submarine was sold for scrap and broken up in 1927.

Design and description

[edit]Ordered as part of the War Emergency Programme from Bethlehem Steel of the United States, the H class were constructed at two shipyards, Canadian Vickers in Montreal and the Fore River Yard in Quincy, Massachusetts based on the US H-class design.[1][2] The boats displaced 364 long tons (370 t) while surfaced and 434 long tons (441 t) submerged. They were 45.8 metres (150 ft 3 in) long overall with a beam of 4.6 metres (15 ft 1 in) and a draught of 3.68 metres (12 ft 1 in).[1] They had a complement of 4 officers and 18 ratings.[1][3]

The submarines were powered by a twin-shift, 480 horsepower (360 kW) Vickers diesel and two 620 hp (460 kW) electric motors. This gave the boats a maximum surfaced speed of 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph) and a submerged speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[1] They had a fuel capacity of 16 long tons (16 t) of diesel fuel.[4] This gave them a range of 1,600 nautical miles (3,000 km; 1,800 mi) at 10 knots while surfaced.[1] The H class had a designed diving depth of 200 metres (660 ft).[5] The submarines were armed with four 18 inch (450 mm) tubes in the bow for the six torpedoes they carried.[1][3]

Operational history

[edit]Royal Navy service

[edit]HMS H14 was ordered in December 1914 from Bethlehem Steel, constructed at the Fore River Yard in Quincy, Massachusetts, and completed in December 1915.[6] Due to the neutrality of the United States at the time, the submarines were constructed in secret and the vessel's launch date was not recorded. The intention was to construct the submarines and deliver them unarmed to Canada, where their armament would be installed.[1] When the American government discovered the construction, they impounded H14 and her nine completed sister boats, only releasing them following their own declaration of war two years later.[7] During their internement, six of the ten completed submarines were ceded to Chile, leaving four at the Fore River Shipyard. Following the US entry into the war, the remaining four submarines were to sail to the United Kingdom by March 1918.[7]

On 29 March, H14 got underway with three of her sister boats for the United Kingdom,[8] via Bermuda. On 15 April, H14 departed Bermuda for the Azores in a group that consisted of some 40 Allied ships led by USS Salem. Shortly after leaving port, H14 collided with the oiler Arethusa, necessitating a return to Bermuda. H14 was towed back to Bermuda by Conestoga on 18 April.[9] The vessel returned to Boston with serious defects.[8]

After repairs, H14 and sister boat H15 sailed for the United Kingdom, departing the United States on 9 November.[10][11] The war ended while in transit and the two subs were ordered to Bermuda where they were laid up.[12] The two subs were placed in reserve there until December 1918 when Canada agreed to their transfer from the Royal Navy.[13]

Royal Canadian Navy service

[edit]H14 and H15 were officially transferred to the Royal Canadian Navy on 7 February 1919.[14] Taken to Halifax, Nova Scotia in May 1919, H14 lay in a state of disrepair until April 1920 when the Royal Canadian Navy decided to refit and commission the submarine.[13][15] The H class was used to replace the CC-class submarines.[16] The two submarines were commissioned at Halifax on 21 April 1922.[3] CH-14 became operational in August and with her sister boat, made a series of port visits around the Maritimes. During the winter months of 1921–22, the two submarines sailed to Bermuda for training exercises.[17] Due to budget cuts, plans were made to get rid of the H-class submarines and CH-14 was paid off on 30 June 1922.[18] In 1923, the Royal Canadian Navy began planning to reactivate the submarines. However, this proved too costly and instead the submarine was sold for scrap in 1927.[3][19]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Gardiner and Gray, p. 92

- ^ Jane's Fighting Ships of World War I, p. 99

- ^ a b c d Macpherson and Barrie, p. 16

- ^ Cocker, pp. 40–41

- ^ Ferguson, p. 55

- ^ Perkins, J. D. (1999). "Electric Boat Company Holland Patent Submarines: Building History and Technical Details for Canadian CC-Boats and the Original H-CLASS". Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- ^ a b Perkins (1989), pp. 187–188

- ^ a b Perkins (1989), p. 188

- ^ Cressman, Robert J. (6 December 2005). "Bridgeport". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. United States Navy. Retrieved 29 October 2007.)

- ^ Perkins (1989), p. 191

- ^ Ferguson, p. 98

- ^ Perkins (1989), p. 194

- ^ a b Perkins (1989), p. 203

- ^ Ferguson, p. 104

- ^ Ferguson, p. 105

- ^ German, p. 42

- ^ Perkins (1989), p. 208

- ^ Ferguson, p. 107

- ^ Ferguson, p. 208

Sources

[edit]- Cocker, Maurice (2008). Royal Navy Submarines: 1901 to the Present Day. Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84415-733-4.

- Ferguson, Julie H. (1995). Through a Canadian Periscope: The Story of the Canadian Submarine Service. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 1-55002-217-2.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1986). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- German, Tony (1990). The Sea is at Our Gates: The History of the Canadian Navy. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Incorporated. ISBN 0-7710-3269-2.

- Jane's Fighting Ships of World War I. New York: Military Press. 1990 [1919]. ISBN 0-517-03375-5.

- Macpherson, Ken; Barrie, Ron (2002). The Ships of Canada's Naval Forces 1910–2002 (Third ed.). St. Catharines, Ontario: Vanwell Publishing. ISBN 1-55125-072-1.

- Perkins, Dave (1989). Canada's Submariners 1914–1923. Erin, Ontario: The Boston Mills Press. ISBN 1-55046-014-5.

- Perkins, J. David (2000). The Canadian Submarine Service in Review. St. Catharines, Ontario: Vanwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-55125-031-4.