Highlands Air Force Station

| Highlands Air Force Station USAF transmitter call sign: "Jitney" | |

|---|---|

| Part of Air Defense Command | |

| Coordinates | 40°23′29″N 073°59′38″W / 40.39139°N 73.99389°W |

| Type | General Surveillance Radar Station |

| Code | L-12: 1948 Lashup Radar Network P-9: 1949 ADC permanent network Z-9: 1963 July 31 NORAD network |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | |

| Site history | |

| In use | 1948-1966 |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | Major Weston F. Griffith (1955-1961) |

| Garrison | |

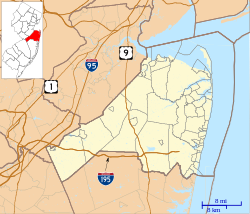

Highlands Air Force Station was a military installation in Middletown Township near the borough of Highlands, New Jersey.[1] The station provided ground-controlled interception radar coverage as part of the Lashup Radar Network and the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment network, as well as providing radar coverage for the Highlands Army Air Defense Site. The site's 240 acres (97 ha)[1] is now the Rocky Point section in Hartshorne Woods Park of the Monmouth County Parks System.

The Navesink Military Reservation (also called the Highlands Military Reservation) was added as a historic district to the National Register of Historic Places on 13 October 2015.[2]

History

[edit]Early installations

[edit]The Navesink Highlands had a sea navigation beacon in 1746,[4] and the first Navesink Twin Lights lighthouse was built in 1828. The current Navesink Twin Lights lighthouse was built in 1862.[5] The Navesink Highlands were used for antebellum flag signaling experiments that communicated with Fort Tompkins on Staten Island in 1859.[6]: 30 In 1899 Guglielmo Marconi built a radio station on the hill next to the north tower of the Navesink Twin Lights to report on the America's Cup races off of Sandy Hook.[5]

Seacoast defense and 1930s radar testing

[edit]Navesink Military Reservation Historic District | |

Battery Lewis - Casemate front | |

| Location | Grand Tour Road and Portland Road, Middletown Township, New Jersey |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°23′26″N 73°59′20″W / 40.39056°N 73.98889°W |

| NRHP reference No. | 15000011[7] |

| NJRHP No. | 5389[8] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | 13 October 2015 |

| Designated NJRHP | 28 August 2015 |

In 1917 during World War I, four 12-inch coast defense mortars were placed on the Navesink Highlands for seacoast defense, transferred from the mortar batteries at Fort Hancock, New Jersey on Sandy Hook. These were called Battery Hartshorne.[9][10][11] The battery was named for Richard Hartshorne, a settler who acquired the land in the 1670s.[12][13] This battery was disarmed in 1920. By 1933, Harold A. Zahl's radio range experiments had begun from the Twin Lights lighthouse,[14] and an August 1935 US Army Signal Corps radar test at the lighthouse allowed a searchlight beam to track an aircraft.[15] An SCR-268 radar assembled in August 1938 was demonstrated at the Twin Lights lighthouse in 1939.[16] In 1942-44 the Navesink (or Highlands) Military Reservation was built, which included Battery Isaac N. Lewis (also called Battery 116), a casemated coastal defense battery of two 16"/50 caliber Mark 2 guns, along with Battery 219, a coastal defense battery of two 6-inch M1903 guns on the hill to the south of the Twin Lights Lighthouse.[10][11][17] The batteries were garrisoned by the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps as part of the Harbor Defenses of New York. Battery Lewis was one of the primary batteries guarding Greater New York in World War II, along with another 16-inch battery at Fort Tilden in Queens and two 12-inch long-range batteries at Fort Hancock on Sandy Hook.[9] These rendered all previous heavy guns in the area obsolete, and these were gradually scrapped during the war.[10] After World War II it was determined that gun defenses were obsolete, and the guns at Navesink were scrapped in 1948.[17]

Twin Lights station

[edit]The Twin Lights Aircraft Warning Corps Site 8A was an Army radar site that reported radar data to an Information Filter and Control Center in the New York Telephone building (now the Verizon Building) in New York City during World War II. The station was used for a November 1939[16] demonstration for the Secretary of War in which radar data was networked from the local SCR-270 radar and, via telephone, from one in Connecticut that both tracked[18] a Mitchel Field[19] B-17 bomber formation. From 1942 to 1945, the site had a World War II Westinghouse SCR-271 radar for early warning. The site was operated by the 608th Signal Aircraft Warning Battalion. Between 1946 and June 1948 the site was operated as a research field station by the Lt. Colonel Paul E. Watson Laboratories in Red Bank, New Jersey. Watson Laboratories set up an experimental model of an AN/CPS-6 Radar which was developed at the end of World War II by M.I.T. After the 1948 Berlin Blockade in Germany, the Cold War was on and with the appearance of the Soviet Tupolev Tu-4 intercontinental bomber in 1947, a major concern of the United States was a possible attack by Soviet long-range bombers. In 1948, the United States Air Force (USAF) directed its Air Defense Command (ADC) to take radar sets out of storage for operation in the Northeastern United States. In June 1948, Air Defense Command activated the 646th Aircraft Control and Warning Squadron at the Twin Light Lashup Site L-12 with the Watson Laboratories General Electric AN/CPS-6 Radar and an AN/TPS-1B radar providing radar data to the Manual Control Center at Roslyn Air Warning Station, New York as part of the Lashup Radar Network. In December 1950, 646th Aircraft Control and Warning Squadron moved from the Twin Lights Lashup site to the Navesink Military Reservation with a new General Electric AN/CPS-6 Radar. In July 1951 the Air Defense Command accepted the new radar and designated the site P-9 as the 9th new Permanent radar site in the nation as part of the Air Defense Command Permanent radar network. In December 1953 the Navesink Military Reservation was renamed to the Highlands Air Force Station. In 1955 a General Electric AN/FPS-8 Radar for medium range surveillance was installed to augment the radar data of the General Electric AN/CPS-6 Radar and was (later converted to a General Electric AN/GPS-3 Radar[20] that remained until 1960.) Nine units of officers housing were built in 1955 near Battery 219. In March 1957 the Highlands Air Force Station began operating the first Bendix AN/FPS-14 Radar in the nation at the radar Gap Filler site P-9A in Gibbsboro, New Jersey until 1960. In 1958, four General Electric AN/FPS-6 Radar were added to the site along with a General Electric AN/FPS-7 Radar.

SAGE site

[edit]In 1958, Highlands Air Force Station began providing data to Semi Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) Direction Center DC-01 at McGuire AFB which had Air Defense Command interceptor aircraft and CIM-10 Bomarc surface-to-air missiles. In September 1959, the Highlands Air Force Station was the first site in the nation with a General Electric AN/FPS-7 Radar used for long range surveillance for the Martin AN/FSG-1 Antiaircraft Defense System and the Air Force.[9] (The 1262nd U.S. Army Signal Missile Master Support Detachment provided site maintenance to the Martin AN/FSG-1 Antiaircraft Defense System from 1960 to 1966.[21][22]) The Missile Master at the Highlands Air Force Station was the Army's command post for the New York-Philadelphia Defense Area and was designated as Nike Site NY-55DC and was a NORAD Control Center. It was operated by the 52nd Artillery Brigade (Air Defense). Texas Tower 4 (call sign "Dora") was an offshore radar annex of Highlands Air Force Station operated by a 646th Radar Squadron (SAGE) from 1958 until it collapsed into the Atlantic Ocean on 15 January 1961, killing 28 people. The Highlands Air Force Station had an AN/FRC-56 Tropospheric scatter Communications shore station which communicated with the Texas Tower 4. In 1960 the Air Force installed an AN/FPS-6B height-finder radar at Highlands which, along with the AN/FPS-6, had been replaced by 1963 with AN/FPS-26A and AN/FPS-90 sets. On 31 July 1963 the site was redesignated as NORAD ID Z-9. The United States Secretary of Defense announced on 20 November 1964, that the Air Force operations would be closed.[23]

The Highlands Army Air Defense Site (HAADS) was established in 1966 with the first Hughes AN/TSQ-51 Air Defense Command and Coordination System in the nation. This replaced the Martin AN/FSG-1 Antiaircraft Defense System in the Missile Master nuclear-hardened bunker, which used radar data to guide Nike missiles. HAADS assumed control of the USAF station after the DoD announced its closure for July 1966.[1][24] The 646th Radar Squadron (SAGE) was inactivated on 1 July 1966. The Army's use of the site ended in 1974 under Project Concise when the Nike missile program ended.[25] Most of the buildings were demolished in the mid-1980s and mid 1990s,[26] and a few building foundations remain in a small clearing within the site's overgrowth of vegetation. However, the concrete remains of Battery Lewis, Battery 219, and the Plotting and Switchboard Bunker still stand.[27]

Present

[edit]The area is now Hartshorne Woods Park. In January 2017 a retired US Navy 16"/50 caliber Mark 7 gun, formerly a spare for the Iowa-class battleships, was placed on display in one of the gun positions of Battery Lewis.

| External image | |

|---|---|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Highlands Radar Site Closing" (PDF). The Daily Register. Red Bank, New Jersey. 20 November 1964. p. One. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

Gov. Richard J. Hughes said yesterday he had been informed that a radar unit at the Air Force facility would be inactivated by July, 1966, affecting approximately 19 civilian employees and 186 military personnel.... Lt. Col. Ralph W. Frank, Jr., commander of the Air Force Station, indicated that the U.S. Army radar unit stationed at the base will be left intact.... The Army radar unit consists of approximately 300 men, of which about 200 are tied in with Fort Hancock operations or Sandy Hook as part of the U.S. Army Defense Command, according to the Air Force base commander.... According to the base commander, the entire Highlands Air Force Station, including the Missile Master, occupies about 241 acres, of which 103 undeveloped acres have been approved by the assistant secretary of defense as surplus property.... If land were to become available, it's probable that Middletown Township would have first claim on it, Mayor Guiney said. The installation, though named for this borough, is actually located in the township, the mayor reported, but it is serviced by the Highlands Post Office. "Geographically, Middletown could gain from this – possibly new ratables," said Mayor Guiney.

- ^ "Navesink Military Reservation Historic District". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016.

- ^ "Location of the Missile Master" (PDF). Red Bank Register. Red Bank, New Jersey. 7 August 1958. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ^ "646th Radar Squadron (SAGE)". New York Air Defense Sector Yearbook. 1960. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ^ a b King, John P. (2001). Highlands: New Jersey. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-2362-3.

- ^ Rauch, Steven J. "Edward P. Alexander versus Albert J. Myer: Success and failure at the Battle of Bull Run" (PDF). United States Army Communicator: Voice of the Signal Regiment. 36 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

Both Myer and Alexander…carried out a final series of trials with Myer stationed on the New Jersey Highlands and Alexander 15 miles away at Fort Tompkins on Staten Island. … Alexander…could read signals made with a four-foot flag on a 12-foot pole "with [only] a small and weak glass."

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 9 July 2010.

- ^ "New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places - Monmouth County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection - Historic Preservation Office. 22 August 2016. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2014.

- ^ a b c "The Historic Atlantic Highlands Military Reservation (MR)". Fort Tilden. 11 November 2005. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

Battery 219, Atlantic Highlands MR, NJ … This same plot of land on the Atlantic Highlands was later used as a control center for Nike air defense missiles during the Cold War.... Many Army units were based here: HQ 52nd [Air Defense Artillery] Brigade: November 1968 to September 1972, HQ 19th Group [19th Artillery Group HAADS]: December 1961 to November 1968, HQ 16th Group: June 1971 to September 1974, HHB/3/51st: November 1968 to September 1972..., HHB/1/51st: September 1972 to June 1973.

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - ^ a b c Berhow, p. 210

- ^ a b "New Jersey Forts". northamericanforts.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2010.

- ^ "Richard Hartshorne at HighlandsNJ.com". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- ^ "Richard Hartshorne at RichardRiis.com". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- ^ "Chapter 4 - Cultural Resources Report - 1996". 1996. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- ^ Davis, Harry M. (1st Lt) (1972) [1943, declassified 1972]. "Chapter IV". The Signal Corps Development of U.S. Army Radar Equipment. Signal Corps. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

The Ordnance Department, which had voluntarily relinquished the "[radar]" project to the Signal Corps in 1930, now argued…that the data from a short-wave radio detector might eventually be applied directly to the gun director, eliminating the searchlight and replacing the sound locator. …the opening of the new Squier Laboratory building at Fort Monmouth, the personnel on 30 June 1936 consisted of only eight officers, seventeen enlisted men and ninety-two civilians.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Vieweger, Arthur L; White, Albert S. (1956). Development of Radar SCR-270 (Report). p. 23. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

Such radars were therefore imported from England for analysis and comparison in a field set-up at the Signal Corps Radar Laboratory, in Belmar, N. J. … final version of SCR-271 with… Transmitter Peak Power - 500 KW (using the same WL-350 tubes); Pulse Width - 20 microseconds - Antenna - 64 dipoles 8 × 8 configuration; Antenna Beam Width Approx. 10° … at Oakhurst, N. J. … "Diana" using the major components of SCR-271…succeeded in…receiving echoes from the moon in January 1946.

- ^ a b "Highlands Military Reservation - FortWiki Historic U.S. and Canadian Forts". fortwiki.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- ^ McKinney, John B. (August 2006). "Radar: A Case History of an Invention" (PDF). IEEE A&E Systems Magazine. 21 (8 Part II).[permanent dead link]

- ^ Terrett, Dulany (1994) [1956 - CMH Pub 10-16-1]. The Signal Corps: The Emergency (To December 1941) (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History. LCCN 56-6002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

Secretary Woodring was discovered to have brushed the stop button on the rectifier unknowingly.

- ^ The AN/GPS-3 is composed of a surveillance radar set,[e.g., radar set of the AN/FPS-8] Tower AB-397/FPS-8, and Radar Recognition Set AN/UPX-6. Source: MIL-HDBK-162A Radar Set, Integrated Publishing, 15 April 1964

- ^ "TEMPORARY TEAM (photo caption)" (PDF). The Daily Register. 20 November 1964. p. One. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

Lt. Col. Ralph W. Frank, Jr., left, commander of Highlands Air Force Station, and Capt. John W. Nolan, commanding officer of U. S. Army Signal Support Detachment stationed at bate, review roster of men to be detached from installation under directive issued yesterday by U.S, Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara. Air Force personnel will be inactivated by July, 1966, leaving Army radar unit at base intact, according to Lt, Col. Frank.

- ^ "Awarded Army Medal" (PDF). Red Bank Register. 5 June 1964. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2012.

- ^ Fay, Elton C. (20 November 1964). "What's Behind Decision" (PDF). The Daily Register. Washington, DC. p. One. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

Over the past four years 574 U.S. military bases around the world... have been closed or their activities sharply cutback. Thursday, he tacked another 95 to the list.... McNamara struck 16 more Air Defense Command radar stations from the category of necessary installations.

- ^ "McNamara Firm on Base Shutdowns" (PDF). The Daily Register. Red Bank, New Jersey. 20 November 1964. p. One. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

The latest stroke of McNamara's economy scalpel cut at two naval shipyards employing a total of 17,000 workers, six bomber bases, Army and Air Force training sites, arsenals, radar posts and other installations in 33 states and the District of Columbia.... The actions will be completed for the most part by mid-1966...

- ^ "Chapter IX Logistics". Department of the Army Historical Summary: Fiscal Year 1974. Center of Military History. 1978. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ Payette, Pete (21 February 2011). "New Jersey Forts". American Forts Network. Archived from the original on 17 November 2010.

- ^ "Military - The Lostinjersey Blog - Page 3". lostinjersey.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide (Third ed.). McLean, Virginia: CDSG Press. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

External links

[edit]- List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coast Defense Study Group, Inc. website

- FortWiki, lists most CONUS and Canadian forts

- Installations of the United States Air Force in New Jersey

- Radar stations of the United States Air Force

- Forts in New Jersey

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in New Jersey

- National Register of Historic Places in Monmouth County, New Jersey

- New Jersey Register of Historic Places

- Middletown Township, New Jersey

- Radar pioneers

- World War II sites in the United States

- 1966 disestablishments in New Jersey