Republic of Sudan (1985–2019)

Republic of the Sudan | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985–2019 | |||||||||||

Map of Sudan before South Sudanese independence on July 9, 2011 | |||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Khartoum 15°38′N 032°32′E / 15.633°N 32.533°E | ||||||||||

| Official languages |

| ||||||||||

| Ethnic groups | |||||||||||

| Religion | Islam (official) | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Sudanese | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary provisional government under a military junta (1985–1986) Unitary parliamentary republic (1986–1989) Unitary one party Islamic Republic (1989–1998)

| ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

• 1985–1986 | Abdel Rahman Swar al-Dahab | ||||||||||

• 1986–1989 | Ahmed al-Mirghani | ||||||||||

• 1989–2019 | Omar al-Bashir | ||||||||||

| Prime minister | |||||||||||

• 1985–1986 | Al-Jazuli Daf'allah | ||||||||||

• 1986–1989 | Sadiq al-Mahdi | ||||||||||

• 1989–2017 | Post abolished | ||||||||||

• 2017–2018 | Bakri Hassan Saleh | ||||||||||

• 2018–2019 | Motazz Moussa | ||||||||||

• 2019 | Mohamed Tahir Ayala | ||||||||||

| Legislature | National Legislature | ||||||||||

| Council of States | |||||||||||

| National Assembly | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War, War on Terror | ||||||||||

| 6 April 1985 | |||||||||||

| April 1986 | |||||||||||

| 30 June 1989 | |||||||||||

| 23 April 1990 | |||||||||||

| 27 May 1998 | |||||||||||

| 9 January 2005 | |||||||||||

| January 2011 | |||||||||||

| 2018–2019 | |||||||||||

| 11 April 2019 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1985 | 2,530,397 km2 (976,992 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| 2011 | 1,886,086 km2 (728,222 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

| History of Sudan | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Before 1956 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Since 1955 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| By region | ||||||||||||||||||

| By topic | ||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

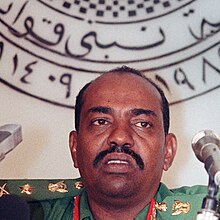

President of Sudan 1989-2019

Government

Wars

|

||

This article covers the period of the history of Sudan between 1985 and 2019 when the Sudanese Defense Minister Abdel Rahman Swar al-Dahab seized power from Sudanese President Gaafar Nimeiry in the 1985 Sudanese coup d'état. Not long after, Lieutenant General Omar al-Bashir, backed by an Islamist political party, the National Islamic Front, overthrew the short lived government in a coup in 1989 where he ruled as President until his fall in April 2019. During Bashir's rule, also referred to as Bashirist Sudan, or as they called themselves the al-Ingaz regime, he was re-elected three times while overseeing the independence of South Sudan in 2011. His regime was criticized for human rights abuses, atrocities and genocide in Darfur and allegations of harboring and supporting terrorist groups (most notably during the residency of Osama bin Laden from 1992 to 1996) in the region while being subjected to United Nations sanctions beginning in 1995, resulting in Sudan's isolation as an international pariah.

History

[edit]Al Mahdi government

[edit]In June 1986, Sadiq al-Mahdi formed a coalition government with the National Umma Party (NUP), the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the National Islamic Front (NIF), and four southern parties. Party factionalism, corruption, personal rivalries, scandals, and political instability characterized the Sadiq regime. After less than a year in office, Sadiq dismissed the government because it had failed to draft a new penal code to replace Sharia law, reach an agreement with the IMF, end the civil war in the south, or devise a scheme to attract remittances from Sudanese expatriates. To retain the support of the DUP and the southern political parties, Sadiq formed another ineffective coalition government.

Instead of removing the ministers who had been associated with the failures of the first coalition government, Sadiq retained thirteen of them, of whom eleven kept their previous portfolios. As a result, many Sudanese rejected the second coalition government as being a replica of the first. To make matters worse, Sadiq and DUP leader Ahmed al-Mirghani signed an inadequate memorandum of understanding that fixed the new government's priorities as affirming the application of the Sharia to Muslims, consolidating the Islamic banking system, and changing the national flag and national emblem. Furthermore, the memorandum directed the government to remove former leader Nimeiry's name from all institutions and dismiss all officials appointed by Nimeiry to serve in international and regional organizations. As expected, anti-government elements criticized the memorandum for not mentioning the civil war, famine, or the country's disintegrating social and economic conditions.[citation needed]

In August 1987, the DUP brought down the government because Sadiq opposed the appointment of a DUP member, Ahmad as Sayid, to the Supreme Commission. For the next nine months, Sadiq and al-Mirghani failed to agree on the composition of another coalition government. During this period, Sadiq moved closer to the NIF. However, the NIF refused to join a coalition government that included leftist elements. Moreover, Hassan al-Turabi, leader of the NIF indicated that the formation of a coalition government would depend on numerous factors, the most important of which were the resignation or dismissal of those serving in senior positions in the central and regional governments, the lifting of the state of emergency reimposed in July 1987, and the continuation of the Constituent Assembly.[citation needed]

Because of the endless debate over these issues, it was not until May 15, 1988, that a new coalition government emerged headed by Sadiq al Mahdi. Members of this coalition included the Umma, the DUP, the NIF, and some southern parties. As in the past, however, the coalition quickly disintegrated because of political bickering among its members. Major disagreements included the NIF's demand that it be given the post of commissioner of Khartoum, the inability to establish criteria for the selection of regional governors, and the NIF's opposition to the replacement of senior military officers and the chief of staff of the executive branch.

In August 1988, severe flooding occurred in Khartoum.

In November 1988, another more explosive political issue emerged when Mirghani and the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) signed an agreement in Addis Ababa that included provisions for a cease-fire, the freezing of Sharia law, the lifting of the state of emergency, and the abolition of all foreign political and military pacts. The two sides also proposed to convene a constitutional conference to decide Sudan's political future. The NIF opposed this agreement because of its stand on Sharia. When the government refused to support the agreement, the DUP withdrew from the coalition. Shortly thereafter armed forces commander in chief Lieutenant General Fathi Ahmad Ali presented an ultimatum, signed by 150 senior military officers, to Sadiq al-Mahdi demanding that he make the coalition government more representative and that he announce terms for ending the civil war.

Fall of al-Mahdi and brief NIF regime

[edit]

On March 11, 1989, Sadiq al-Mahdi responded to this pressure by dissolving the government. The new coalition had included the Umma, the DUP, and representatives of southern parties and the trade unions. The NIF refused to join the coalition because the coalition was not committed to enforcing Sharia law. Sadiq claimed his new government was committed to ending the southern civil war by implementing the November 1988 DUP-SPLM agreement. He also promised to mobilize government resources to bring food relief to famine areas, reduce the government's international debt, and build a national political consensus.

Sadiq's inability to live up to these promises eventually caused[citation needed] his downfall. On June 30, 1989, Colonel (later Lieutenant General) Umar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir overthrew Sadiq and established the Revolutionary Command Council for National Salvation to rule Sudan. Bashir's commitment to imposing the Sharia on the non-Muslim south and to seeking a military victory over the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), however, seemed likely to keep the country divided for the foreseeable future and hamper resolution of the same problems faced by Sadiq al-Mahdi. Moreover, the emergence of the NIF as a political force made compromise with the south more unlikely.

The Revolutionary Command Council dissolved itself in October 1993. Its powers were devolved to the President (al-Bashir declared himself the President) and the Transitional National Assembly.

The Popular Police Forces was created in 1989, they were estimated to have at least 35,000 members who technically were under the supervision of the director general of police, but it operated as a politicized militia that sought to enforce “moral standards” among the country's Islamic population.[4] The PPF had a poor human-rights record.[4] It was dissolved by the transitional government after the Sudanese Revolution.[5]

Conflict in the south, Darfur conflict and conflict with Chad

[edit]

The civil war in the south had displaced more than 4 million southerners. Some fled into southern cities, such as Juba; others trekked as far north as Khartoum and even into Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Egypt, and other neighboring countries. These people were unable to grow food or earn money to feed themselves, and malnutrition and starvation became widespread. The lack of investment in the south resulted in what international humanitarian organizations call a “lost generation” who lack educational opportunities, access to basic health care services, and little prospects for productive employment in the small and weak economies of the south or the north.

In early 2003 a new rebellion of the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) groups in the western region of Darfur began. The rebels accused the central government of neglecting the Darfur region, although there is uncertainty regarding the objectives of the rebels and whether they merely seek an improved position for Darfur within Sudan or outright secession. Both the government and the rebels have been accused of atrocities in this war, although most of the blame has fallen on Arab militias (Janjaweed) allied with the government. The rebels have alleged that these militias have been engaging in ethnic cleansing in Darfur, and the fighting has displaced hundreds of thousands of people, many of them seeking refuge in neighboring Chad. There are various estimates on the number of human casualties, ranging from under twenty thousand to several hundred thousand dead, from either direct combat or starvation and disease inflicted by the conflict.

In 2004 Chad brokered negotiations in N'Djamena, leading to the April 8 Humanitarian Ceasefire Agreement between the Sudanese government, the JEM, and the SLA. However, the conflict continued despite the ceasefire, and the African Union (AU) formed a Ceasefire Commission (CFC) to monitor its observance. In August 2004, the African Union sent 150 Rwandan troops in, to protect the ceasefire monitors. It, however, soon became apparent that 150 troops would not be enough, so they were joined by 150 Nigerian troops.

On September 18, 2004 United Nations Security Council issued Resolution 1564 declaring that the government of Sudan had not met its commitments, expressing concern at helicopter attacks and assaults by the Janjaweed militia against villages in Darfur. It welcomed the intention of the African Union to enhance its monitoring mission in Darfur and urged all member states to support such efforts. During 2005 the African Union Mission in Sudan force was increased to about 7,000.

The Chadian-Sudanese conflict officially started on December 23, 2005, when the government of Chad declared a state of war with Sudan and called for the citizens of Chad to mobilize themselves against Rally for Democracy and Liberty (RDL) militants (Chadian rebels backed by the Sudanese government) and Sudanese militiamen who attacked villages and towns in eastern Chad, stealing cattle, murdering citizens, and burning houses.

Peace talks between the southern rebels and the government made substantial progress in 2003 and early 2004, although skirmishes in parts of the south have reportedly continued. The two sides have agreed that, following a final peace treaty, southern Sudan will enjoy autonomy for six years, and after the expiration of that period, the people of southern Sudan will be able to vote in a referendum on independence. Furthermore, oil revenues will be divided equally between the government and rebels during the six-year interim period. The ability or willingness of the government to fulfill these promises has been questioned by some observers, however, and the status of three central and eastern provinces was a point of contention in the negotiations. Some observers wondered whether hard line elements in the north would allow the treaty to proceed.

A final peace treaty was signed on 9 January 2005 in Nairobi. The terms of the peace treaty are as follows:

- The south will have autonomy for six years, followed by a referendum on secession.

- Both sides of the conflict will merge their armed forces into a 39,000-strong force after six years, if the secession referendum should turn out negative.

- Income from oilfields is to be shared evenly between north and south.

- Jobs are to be split according to varying ratios (central administration: 70 to 30, Abyei/Blue Nile State/Nuba mountains: 55 to 45, both in favour of the government).

- Islamic law is to remain in the north, while continued use of the Sharia in the south is to be decided by the elected assembly.

On 31 August 2006, the United Nations Security Council approved Resolution 1706 to send a new peacekeeping force of 17,300 to Darfur. In the following months, however, UNMIS was not able to deploy to Darfur due to the Government of Sudan's steadfast opposition to a peacekeeping operation undertaken solely by the United Nations. The UN then embarked on an alternative, innovative approach to try to begin stabilize the region through the phased strengthening of AMIS, before transfer of authority to a joint African Union/United Nations peacekeeping operation. Following prolonged and intensive negotiations with the Government of Sudan and significant international pressure, the Government of Sudan finally accepted the peacekeeping operation in Darfur.

In 2009 the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for al-Bashir, accusing him of crimes against humanity and war crimes.

In 2009 and 2010 a series of conflicts between rival nomadic tribes in South Kordofan caused a large number of casualties and displaced thousands.

An agreement for the restoration of harmony between Chad and Sudan, signed January 15, 2010, marked the end of a five-year war between them.[6]

The Sudanese government and the JEM signed a ceasefire agreement ending the Darfur conflict in February, 2010.

Partition and rehabilitation

[edit]

The Sudanese conflict in South Kordofan and Blue Nile in the early 2010s between the Army of Sudan and the Sudan Revolutionary Front started as a dispute over the oil-rich region of Abyei in the months leading up to South Sudanese independence in 2011, though it is also related to civil war in Darfur that is nominally resolved, in January 2011 a South Sudanese independence referendum was held, and the south voted overwhelmingly to secede later that year as the Republic of South Sudan, with its capital at Juba and Salva Kiir Mayardit as its first president. Al-Bashir announced that he accepted the result, but violence soon erupted in the disputed region of Abyei, claimed by both the north and the south.

On July 9, 2011, South Sudan became an independent country.[7] A year later in 2012 during the Heglig Crisis Sudan would achieve victory against South Sudan, a war over oil-rich regions between South Sudan's Unity and Sudan's South Kordofan states. The events would later be known as the Sudanese Intifada, which would end only in 2013 after al-Bashir promised he would not seek re-election in 2015. He later broke his promise and sought re-election in 2015, winning through a boycott from the opposition who believed that the elections would not be free and fair. Voter turnout was at a low 46%.[8]

On 13 January 2017, US president Barack Obama signed an Executive Order that lifted many sanctions placed against Sudan and assets of its government held abroad. On 6 October 2017, the following US president Donald Trump lifted most of the remaining sanctions against the country and its petroleum, export-import, and property industries.[9]

2019 Sudanese Revolution and the fall of the Al Bashir regime

[edit]

On 19 December 2018, massive protests began after a government decision to triple the price of goods at a time when the country was suffering an acute shortage of foreign currency and inflation of 70 percent.[10] In addition, President al-Bashir, who had been in power for more than 30 years, refused to step down, resulting in the convergence of opposition groups to form a united coalition. The government retaliated by arresting more than 800 opposition figures and protesters, leading to the death of approximately 40 people according to the Human Rights Watch,[11] although the number was much higher than that according to local and civilian reports. The protests continued after the overthrow of his government on 11 April 2019 after a massive sit-in in front of the Sudanese Armed Forces main headquarters, after which the chiefs of staff decided to intervene and they ordered the arrest of President al-Bashir and declared a three-month state of emergency.[12][13][14] Over 100 people died on 3 June after security forces dispersed the sit-in using tear gas and live ammunition in what is known as the Khartoum massacre,[15][16] resulting in Sudan's suspension from the African Union.[17] Sudan's youth had been reported to be driving the protests.[18] The protests came to an end when the Forces for Freedom and Change (an alliance of groups organizing the protests) and Transitional Military Council (the ruling military government) signed the July 2019 Political Agreement and the August 2019 Draft Constitutional Declaration.[19][20] The transitional institutions and procedures included the creation of a joint military-civilian Sovereignty Council of Sudan as head of state, a new Chief Justice of Sudan as head of the judiciary branch of power, Nemat Abdullah Khair, and a new prime minister. The former Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok, a 61-year-old economist who worked previously for the UN Economic Commission for Africa, was sworn in on 21 August 2019.[21] He initiated talks with the IMF and World Bank aimed at stabilising the economy, which was in dire straits because of shortages of food, fuel and hard currency. Hamdok estimated that US$10bn over two years would suffice to halt the panic, and said that over 70% of the 2018 budget had been spent on civil war-related measures. The governments of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates had invested significant sums supporting the military council since Bashir's ouster.[22] On 3 September, Hamdok appointed 14 civilian ministers, including the first female foreign minister and the first Coptic Christian, also a woman.[23][24] As of August 2021, the country was jointly led by Chairman of the Transitional Sovereign Council, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok.[25]

Foreign policy

[edit]

From the early 1990s, after al-Bashir assumed power, Sudan backed Iraq in its invasion of Kuwait[26][27] and was accused of harboring and providing sanctuary and assistance to Islamic terrorist groups. Carlos the Jackal, Osama bin Laden, Abu Nidal and others labeled "terrorist leaders" by the United States and its allies resided in Khartoum. Sudan's role in the Popular Arab and Islamic Congress (PAIC), spearheaded by Hassan al-Turabi, represented a matter of great concern to the security of American officials and dependents in Khartoum, resulting in several reductions and evacuations of American personnel from Khartoum in the early to mid 1990s.[28]

Sudan's Islamist links with international terrorist organizations represented a special matter of concern for the American government, leading to Sudan's 1993 designation as a state sponsor of terrorism and a suspension of U.S. Embassy operations in Khartoum in 1996. In late 1994, in an initial effort to reverse his nation's growing image throughout the world as a country harboring terrorists, Bashir secretly cooperated with French special forces to orchestrate the capture and arrest on Sudanese soil of Carlos the Jackal.[29]

In early 1996, al-Bashir authorized his Defense Minister at the time, El Fatih Erwa, to make a series of secret trips to the United States[30] to hold talks with American officials, including officers of the CIA and United States Department of State about American sanctions policy against Sudan and what measures might be taken by the Bashir regime to remove the sanctions. Erwa was presented with a series of demands from the United States, including demands for information about Osama bin Laden and other radical Islamic groups. The US demand list also encouraged Bashir's regime to move away from activities, such as hosting the Popular Arab and Islamic Congress, that impinged on Sudanese efforts to reconcile with the West. Sudan's Mukhabarat (central intelligence agency) spent half a decade amassing intelligence data on bin Laden and a wide array of Islamists through their periodic annual visits for the PAIC conferences.[31] In May 1996, after the series of Erwa secret meetings on US soil, the Clinton Administration demanded that Sudan expel Bin Laden. Bashir complied.[32]

Controversy erupted about whether Sudan had offered to extradite bin Laden in return for rescinding American sanctions that were interfering with Sudan's plans to develop oil fields in southern areas of the country. American officials insisted the secret meetings were agreed only to pressure Sudan into compliance on a range of anti-terrorism issues. The Sudanese insisted that an offer to extradite bin Laden had been made in a secret one-on-one meeting at a Fairfax hotel between Erwa and the then CIA Africa Bureau chief on condition that Washington end sanctions against Bashir's regime. Ambassador Timothy M. Carney attended one of the Fairfax hotel meetings. In a joint opinion piece in the Washington Post Outlook Section in 2003, Carney and Ijaz argued that in fact the Sudanese had offered to extradite bin Laden to a third country in exchange for sanctions relief.[33]

In August 1996, American hedge-fund manager Mansoor Ijaz traveled to Sudan and met with senior officials including al-Turabi and al-Bashir. Ijaz asked Sudanese officials to share intelligence data with US officials on bin Laden and other Islamists who had traveled to and from Sudan during the previous five years. Ijaz conveyed his findings to US officials upon his return, including Sandy Berger, then Clinton's deputy national security adviser, and argued for the US to constructively engage the Sudanese and other Islamic countries.[34] In April 1997, Ijaz persuaded al-Bashir to make an unconditional offer of counterterrorism assistance in the form of a signed presidential letter that Ijaz delivered to Congressman Lee H. Hamilton by hand.[35]

In late September 1997, months after the Sudanese overture (made by al-Bashir in the letter to Hamilton), the U.S. State Department, under Secretary of State Madeleine Albright's directive, first announced it would return American diplomats to Khartoum to pursue counterterrorism data in the Mukhabarat's possession. Within days, the U.S. reversed that decision[36] and imposed harsher and more comprehensive economic, trade, and financial sanctions against Sudan, which went into effect in October 1997.[37] In August 1998, in the wake of the East Africa embassy bombings, the U.S. launched cruise missile strikes against Khartoum.[38] U.S. Ambassador to Sudan, Tim Carney, departed post in February 1996[39] and no new ambassador was designated until December 2019, when U.S. president Donald Trump's administration reached an agreement with the new Sudanese government to exchange ambassadors.[40]

Al-Bashir announced in August 2015 that he would travel to New York in September to speak at the United Nations. It was unclear to date if al-Bashir would have been allowed to travel, due to previous sanctions.[41] in 1997, after the U.S. placed sanctions on Sudan, banning all American companies from engaging in its oil sector, after allegations that the government of Omar al-Bashir was supporting terrorists and committing human rights violations.[42] Bashir decided to travel to China in 1995 to request help in developing its oil sector and, this time, China agreed. This appeal came at an opportune moment since China had grown considerable interest in acquiring foreign oil reserves as its own oilfields had already surpassed peak production.[43]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ People and Society CIA world factbook

- ^ الجهاز المركزي للتعبئة العامة والإحصاء

- ^ Sudanese Fulani in Sudan

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

loc2015was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ S/2020/614 - UNITAMS

- ^ World Report 2011: Chad. Human Rights Watch. 24 January 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ^ Martell, Peter (2011). "BBC News - South Sudan becomes an independent nation". BBC. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ "Omar al-Bashir wins Sudan elections by a landslide". BBC News. 27 April 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Wadhams, Nick; Gebre, Samuel (6 October 2017). "Trump Moves to Lift Most Sudan Sanctions". Bloomberg Politics. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ "Sudan December 2018 riots: Is the regime crumbling?". CMI – Chr. Michelsen Institute. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "Sudan: Protesters Killed, Injured". Human Rights Watch. 9 April 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "Sudan military coup topples Bashir". 11 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ "Sudan's Omar al-Bashir vows to stay in power as protests rage | News". Al Jazeera. 9 January 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Arwa Ibrahim (8 January 2019). "Future unclear as Sudan protesters and president at loggerheads | News". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ "Sudan's security forces attack long-running sit-in". BBC News. 3 June 2019.

- ^ ""Chaos and Fire" – An Analysis of Sudan's June 3, 2019 Khartoum Massacre – Sudan". ReliefWeb. 5 March 2020.

- ^ "African Union suspends Sudan over violence against protestors – video". The Guardian. 7 June 2019. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ "'They'll have to kill all of us!'". BBC News. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "(الدستوري Declaration (العربية))" [(Constitutional Declaration)] (PDF). raisethevoices.org (in Arabic). FFC, TMC. 4 August 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Reeves, Eric (10 August 2019). "Sudan: Draft Constitutional Charter for the 2019 Transitional Period". sudanreeves.org. FFC, TMC, IDEA. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "We recognize Hamdok as leader of Sudan's transition: EU, Troika envoys". Sudan Tribune. 27 October 2021. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ Abdelaziz, Khalid (24 August 2019). "Sudan needs up to $10 billion in aid to rebuild economy, new PM says". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "Sudan's PM selects members of first cabinet since Bashir's ouster". Reuters. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Women take prominent place in Sudanese politics as Abdalla Hamdok names cabinet". The National. 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Sudan Threatens to Use Military Option to Regain Control over Border with Ethiopia". Asharq Al-Awsat. 17 August 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Middleton, Drew (4 October 1982). "Sudanese Brigades Could Provide Key Aid for Iraq; Military Analysis". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Perlez, Jane (26 August 1998). "After the Attacks: The Connection; Iraqi Deal with Sudan on Nerve Gas Is Reported". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "U.S. – Sudan Relations". U.S. Embassy in Sudan. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ "Carlos the Jackal Reportedly Arrested During Liposuction". Los Angeles Times. 21 August 1994. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "1996 CIA Memo to Sudanese Official". The Washington Post. 3 October 2001. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "The Osama Files". Vanity Fair. January 2002. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Sudan Expels Bin Laden". History Commons. 18 May 1996. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Carney, Timothy; Mansoor Ijaz (30 June 2002). "Intelligence Failure? Let's Go Back to Sudan". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ "Democratic Fundraiser Pursues Agenda on Sudan". The Washington Post. 29 April 1997. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014.

- ^ Ijaz, Mansoor (30 September 1998). "Olive Branch Ignored". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Carney, Timothy; Ijaz, Mansoor (30 June 2002). "Intelligence Failure? Let's Go Back to Sudan". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Malik, Mohamed; Malik, Malik (18 March 2015). "The Efficacy of United States Sanctions on the Republic of Sudan". Journal of Georgetown University-Qatar Middle Eastern Studies Student Association. 2015 (1): 3. doi:10.5339/messa.2015.7. ISSN 2311-8148.

- ^ McIntyre, Jamie; Koppel, Andrea (21 August 1998). "Pakistan lodges protest over U.S. missile strikes". CNN. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ Miniter, Richard (1 August 2003). Losing Bin Laden: How Bill Clinton's Failures Unleashed Global Terror. Regnery Publishing. pp. 114, 140. ISBN 978-0-89526-074-1.

- ^ Wong, Edward (4 December 2019). "Trump Administration Moves to Upgrade Diplomatic Ties With Sudan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- ^ "Omar al-Bashir to speak at UN Summit in New York". Eyewitness News. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Sudan, Oil, and Human Rights: THE UNITED STATES: DIPLOMACY REVIVED". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ "Sudan, Oil, and Human Rights: CHINA'S INVOLVEMENT IN SUDAN: ARMS AND OIL". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

Sources

[edit] This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

Further reading

[edit]- Woodward, Peter, ed. Sudan After Nimeiri (2013); since 1984 excerpt and text search