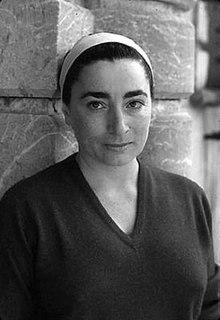

Jacqueline Roque

Jacqueline Picasso | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Jacqueline Marie Madeleine Roque 24 February 1926 Paris, France |

| Died | 15 October 1986 (aged 59) Mougins, France |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 1 |

Jacqueline Picasso or Jacqueline Roque (24 February 1926 – 15 October 1986) was the muse and second wife of Pablo Picasso. Their marriage lasted 12 years until his death, during which time he created over 400 portraits of her, more than any of Picasso's other lovers.[1]

Early life

[edit]Jacqueline Marie Madeleine Roque was born in 1926, 24 February 22h.00 in Paris, France, to Madeleine Antoinette Longuet and Marie Pierre Georges Roque. She was only two when her father abandoned her mother and her five-year-old brother, André Pierre Georges Roque (born November 1924). Her mother raised her in cramped concierge's quarters near the Champs Elysées, while also working long hours as a seamstress. But soon her mother re-married and the family was happy again. Her new father offered Art lover Jacqueline, Violin and classic Dance lessons. Jacqueline was 18 when her mother Madeleine died of a stroke, in 1944. 4 January 1948 she gave birth to her daughter, Catherine Madeleine Blanche Hutin (now married: Hutin-Blay) and Jacqueline married André Hutin, an engineer. The young family moved to Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) in West Africa where Hutin worked as an engineer, but Jacqueline left André and returned to France with Cathy in 1952 and divorced Hutin in November 1954.[2] She settled down on the French Riviera and took a job at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris.[3] She lived in Le Ziquet in Golfe-Juan, Vallauris.

Relationship with Picasso

[edit]Pablo Picasso met Roque in the summer of 1952 while she was working at the Madoura Pottery.[4] At the age of 26, she had taken the role of salesperson in the company's store and was located near to the entrance, where Picasso easily noticed her.[5] He romanced her by drawing a dove on her house in chalk and bringing her one rose a day until she agreed to date him.[6]

Françoise Gilot, Picasso's partner at the time, broke off their relationship at the end of September 1953 and left for Paris with their two children. As she saw Picasso choose and fall in love with Jacqueline. Gilot recalled that when she visited him in July 1954, Picasso continued to live alone, but Roque visited him almost every day.[5] She had been living with her daughter Cathy at a villa at Golfe-Juan named Le Ziquet. According to Picasso's biographer John Richardson, the majority of Picasso's friends disapproved of Roque, while he developed a rapport with her and considered her to be an excellent match for Picasso due to her "submissive and supportive" temperament and the fact that she was "obsessively in love with him."[7] But they were both in love with each other and unlike Françoise, Jacqueline did not compete with him. She made a better match.

In the summer of 1954, Picasso went to stay at the large home of Comte Jacques de Lazarme in Perpignan. He arrived there on 6 August with his daughter Maya and his other two children Claude and Paloma. There they were joined by Douglas Cooper, John Richardson, and later Roland Penrose. Roque and her daughter Cathy also joined the group, but had to stay in a local hotel.[5] When Maya left near the end of August, Roque was allowed to stay in Picasso's room. Two nights later, Picasso and Roque had a huge argument. Patrick O'Brian, a friend of the Lazermes’, recalled that the next morning Roque left to drive to Golfe-Juan, but would stop every hour to speak to Picasso. By the time she reached Béziers, Roque was suicidal. She returned that evening but the argument created a rift between them. O'Brian recalled, "During the next weeks Picasso's attitude towards her was embarrassingly disagreeable, while hers was embarrassingly submissive — she referred to him as her God, spoke to him in the third person and frequently kissed his hands". Richardson opined, "Picasso was testing the limits of Jacqueline's masochistic devotion. This time around, he could not afford another abortive romance. It was up to Jacqueline to prove by the sheer force of her love that she was the best candidate for his hand".[7]

In October 1954, Picasso and Roque began to live together, when she was aged 28 and he was 72.[3] Upon returning to her home in Golfe-Juan, Roque and Picasso found the villa to be too small and moved to Paris. Three days before completing the series of paintings Les Femmes d'Alger, Picasso's estranged wife Olga Khokhlova died, causing Roque and Picasso to return to Cannes.[7] The couple found a private retreat at the Villa La Californie near Mougins.[8] By the end of 1957, Picasso was searching for a new home due to the rise of nearby developments, and bought Château of Vauvenargues in 1958.[7] They married in Vallauris on 2 March 1961.[9] To celebrate their marriage, the couple moved to a villa named Notre-Dame-de-Vie, situated on a hillside near Mougins, where Picasso spent his final 12 years. They were deeply in love with each other and Picasso spent 19 years with her, 12 married.[7]

Picasso's muse

[edit]Roque's image began to appear in Picasso's paintings in 1954. These portraits are characterized by an exaggerated neck and feline face, distortions of Roque's features. Eventually her dark eyes and eyebrows, high cheekbones, and classical profile would become familiar symbols in his late paintings.[10]

Picasso made the first portrait of his second wife on 2 June 1954. It was exhibited at the Maison de la Pensée Français in Paris in July as Portrait de Madame Z, which was inspired by the name of Jacqueline's house Le Ziquet. A second portrait of Jacqueline seated was completed on 3 June.[5]

It is likely that Picasso's series of paintings Les Femmes d'Alger, derived from Eugène Delacroix's The Women of Algiers was inspired by Roque's beauty; the artist commented that "Delacroix had already met Jacqueline."[10] John Richardson commented, "Françoise had not been the Delacroix type. Jacqueline, on the contrary, epitomized it... And then, there is the African connection: Jacqueline had lived for many years as the wife of a colonial official [Hutin] in Upper Volta. As Picasso remarked, 'Ouagadougou may not be Algiers, nonetheless Jacqueline has an African provenance'".[5]

On 28 December 1955, he created Jacqueline with a scarf, a lino cut of Jacqueline as "Lola de Valence", which was a reference to Édouard Manet's 1862 painting of the Spanish dancer.[11][12] In 1963 he painted her portrait 160 times, and continued to paint her, in increasingly abstracted forms, until 1972.[11]

Later life

[edit]Roque was devoted to Picasso throughout their marriage and when he died in 1973, she was deeply affected by grief. Art critic, Richard Dorment stated, "she would sit in a darkened room, sobbing, or address a photograph of her husband as though he were still alive".[13] Richardson observed that whenever he visited Roque after the death of Picasso, she would be utterly distraught, often requiring a doctor to administer tranquillisers. In 1980, her condition seemed to improve and she flew to New York for a Picasso retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. Richardson noted that during his visit to Notre-Dame-de-Vie in 1984 or 1985, she seemed more tormented, often declaring, "Pablo is not dead".[7]

After Picasso's death, Jacqueline prevented his children Claude and Paloma Picasso from attending his funeral, because it was the will of Picasso before he died.[14] Jacqueline also barred Picasso's grandson Pablito Picasso (son of Paolo, Picasso's son from his marriage to the Ukrainian dancer Olga Khokhlova) from attending the service, due to Pablo's conflict with Paolo before his death. Pablito was so distraught he drank a bottle of bleach, dying three months later.[15]

Françoise Gilot, Picasso's companion between 1943 and 1953,[16] and mother of two of his children, Claude and Paloma,[17] fought with Jacqueline over the distribution of the artist's estate. Gilot and her children had unsuccessfully contested the will on the grounds that Picasso was mentally ill.[citation needed]

After the legal battles and death of Picasso's son Paulo Picasso, a French court ruled that the inheritors to the Picasso estate were Jacqueline, his children and grandchildren: Claude, Paloma, Maya, Bernard and Marina Picasso.[18]

Eventually Claude, Paloma and Jacqueline agreed to establish the Musée Picasso in Paris.[11]

Death

[edit]Jacqueline Picasso never recovered from the death of her husband. She had been frequenting Picasso's grave on the eighth of every month and said that he wanted her to join him.[7] She shot herself, with Picasso’s gun, on 15 October 1986[7] in their Mougins home, the chateau where they had spent their married life together;[13] she was 59 years old.[19] She was buried with her husband on the terrace outside the Château of Vauvenargues.[7] Shortly before her death she had confirmed that she would be present at an upcoming exhibit of her private collection of Picasso's work in Spain.[19]

Legacy

[edit]Picasso created more portraits of his second wife than any other woman in his life. John Richardson, Picasso's biographer, described Picasso's final years before his death as "L'Époque Jacqueline". Arne Glimcher, founder of the Pace Gallery commented, "The range of interpretation of her image is quite extraordinary [...] you see the transformation of his late style only through these portraits of Jacqueline."[20]

See also

[edit]- Bust of a Seated Woman (Jacqueline Roque), a 1960 portrait of Roque by Picasso

- Femme au Chien, a 1962 portrait of Roque by Picasso

- La vérité sur Jacqueline et Pablo Picasso, by Pepita Dupont, a book written by Jacqueline Picasso’s close friend at the end of her days that was written to give more details, information and correct disorted information about the couple. An insight into the relationship and Jacqueline’s life. Also translated to Spanish ”La Verdad Sobre Jacqueline y Pablo Picasso”. Unfortunately not in English yet.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Hohenadel (2004).

- ^ Madeline, Laurence (2023). Picasso: 8 femmes. Vanves: Hazan. ISBN 978-2-7541-1234-5.

- ^ a b "The inhabitants of the museum: Jacqueline Roque". Museu Picasso de Barcelona. 4 May 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ "The Mediterranean years". Musée Picasso Paris. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)". Christie's. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ Millard, Ellen (22 January 2020). "Pablo Picasso's women: uncovering the muses behind the artist's pre-eminent portraits". Luxury London. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Richardson, John (1 November 1999). "At the Court of Picasso". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "Pablo Picasso Paysage". Sotheby's. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Art: Artist & Models". Time. 24 March 1961. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ a b Johns (2001), p. 461.

- ^ a b c Johns (2001), p. 462.

- ^ "Jacqueline plate: C.5-1960". The Fitzwilliam Museum. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ a b North, Charlotte (25 September 2018). "Picasso's Muses and the Woman Who Said No". Sotheby's. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Zabel, William D. (1996). The Rich Die Richer and You Can too. New York: John Wiley and Sons. p.11. ISBN 0-471-15532-2. Accessed online 2007-08-15.

- ^ Riding, Alan (24 November 2001). "Grandpa Picasso: Terribly Famous, Not Terribly Nice (Published 2001)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Kazanjian, Dodie (27 April 2012). "Life After Picasso: Françoise Gilot Archived 9 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine." Vogue. Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- ^ Yoakum, Mel (2012). "Introduction: Françoise Gilot." The F. Gilot Archives website. Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- ^ Esterow, Milton (7 March 2016). "The Battle for Picasso's Multi-Billion-Dollar Empire". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b Kimmelman, Michael (28 April 1996). "Picasso's Family Album". New York Times. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Kino, Carol. "Jacqueline Roque: Picasso's Wife, Love & Muse". WSJ. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

References

[edit]- DuPont, Pepita (2007). La vérité sur Jacqueline et Pablo Picasso [The Truth about Jacqueline and Pablo Picasso]. Paris: Cherche midi

- Hohenadel, Kristin (21 March 2004). "Mixing art and commerce." The Los Angeles Times

- Huffington, Arianna Stassinopoulos (1988). Picasso: Creator and Destroyer. New York: Simon & Schuster

- Johns, Cathy (2001). "Roque, Jacqueline." (pp. 458–462). In: Jill Berk Jiminez (Ed.) & Joanna Banham (Assoc. Ed.). Dictionary of Artists' Models. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 1-57958-233-8

- Richardson, John (2001). The Sorcerer's Apprentice: Picasso, Provence, and Douglas Cooper. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-71245-1