Murder of James Bulger

James Bulger | |

|---|---|

| Born | March 16, 1990 |

| Died | February 12, 1993 |

| Cause of death | Murdered |

James "Jamie" Patrick Bulger (March 16, 1990 – February 12, 1993) was a two-year old toddler who was abducted and murdered by two ten-year-old boys, Jon Venables and Robert Thompson (both born in 1982), in Merseyside, in the United Kingdom. The murder of a child by two other children caused an immense public outpouring of shock, outrage, and grief, particularly in Liverpool and surrounding towns. The trial judge ordered that the two boys should be detained for "very, very many years to come". Shortly after the trial, Lord Taylor of Gosforth, the Lord Chief Justice, ordered that the two boys should serve a minimum of 10 years behind bars, which would have made them eligible for release in 2003. But the popular press and certain sections of the public felt that the sentence was too lenient, and the editors of The Sun newspaper handed a petition bearing 300,000 signatures to Home Secretary Michael Howard, in a bid to increase the time spent by both boys in custody. In 1995, the two boys' minimum period to be served was increased to 15 years, a ruling which meant they would not be considered for release until 2008, by which time they would both be 26 years old.

In 1997, however, the Court of Appeal ruled that Michael Howard's decision to set a 15-year tariff was unlawful, and the Home Secretary lost his power to set minimum terms for life-sentence prisoners under the age of 18 years. (In 2002, the position of Home Secretary lost its power to set minimum terms for life sentences entirely).

Thompson and Venables were released on a life license in June 2001, after serving eight years of their life sentence (reduced for good behaviour), when a parole hearing concluded that public safety would not be threatened by their rehabilitation into society. An injunction was imposed, shortly after the trial, preventing the publication of details about the boys, for fear of reprisals by members of the public. The injunction remained in force, following their release, so that details of their new identities and locations could not be published.

Bulger's mother Denise was given £7,500 criminal compensation from the government. The trauma of his death led to the collapse of his parents' marriage; Ralph and Denise Bulger have both since re-married to other people.

The murder

Jon Venables and Robert Thompson had truanted on February 12, 1993. That day, in Bootle Strand Shopping Centre, they attempted to walk off with a young child. They had succeeded in luring a two-year-old boy away from his mother, and were in the process of taking him out of the shopping centre, when she noticed him missing, ran outside, and called him back. For this, the boys were later charged with attempted abduction; however, the charge was dropped when the jury failed to reach a verdict.

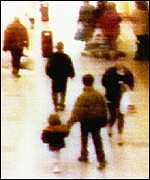

That same afternoon, James Bulger (often called "Jamie Bulger" in press reports), from nearby Kirkby, went on a shopping trip with his mother, Denise. Whilst in a butcher's shop, Mrs Bulger (now Denise Fergus) allowed her son to stand outside in the main concourse of the shopping centre. Within a few minutes, the two boys had taken him by the hand and led him out of the precinct. This moment was captured on a CCTV camera at 15:39.

The boys took Bulger on a 2½ mile (4 km) walk. At one point, they led him to a canal, where he sustained some injuries to his head and face, after apparently being dropped to the ground. Later on in their journey, a witness reported seeing Bulger being kicked in the ribs by one of the boys, to encourage him along.

During the entire walk, the boys were seen by 38 people, some of whom noticed an injury to the child's head and later recalled that he seemed distressed. Others reported that Bulger appeared happy and was seen laughing, the boys seemingly alternating between hurting and distracting him. A few members of the public challenged the two older boys, but they claimed they were looking after their younger brother, or that he was lost and that they were taking him to the police station, and were allowed to continue on their way. They eventually led Bulger to a section of railway line near Walton, Merseyside.

From the facts disclosed at trial, at this location, one of the boys threw blue modeling paint on Bulger's face. They kicked him and hit him with bricks, stones and a 22 lb (10 kg) iron bar. They then placed batteries in his mouth (false reports that the batteries were placed in his rectum were spread by a chain letter.) Before they left him, the boys laid Bulger across the train tracks and weighed his head down with rubble, in hopes that a passing train would hit him and make his death appear to be an accident involving a careless boy and a train. Two days later, on the Sunday of the next week, Bulger's body was discovered; a forensic pathologist later testified that he had died before his body was run over by an oncoming train.

As the circumstances surrounding the death became clear, tabloid newspapers compared the killers with Myra Hindley and Peter Sutcliffe. They denounced the people who had seen Bulger but not realized the trouble he was in as the "Liverpool 38" (see Kitty Genovese, bystander effect). Within days, the Liverpool Echo newspaper had published 1,086 death notices for Bulger. The railway embankment upon which his body had been discovered was flooded with hundreds of bunches of flowers: one of these floral tributes, a single rose, was laid by Thompson. Within days, he and Venables were arrested, after an investigation led by one of Merseyside Police's most senior detectives, Detective Superintendent Albert Kirby.

Forensics tests confirmed that both boys had the same blue paint on their clothing as was found on Bulger's body. Both had blood on their shoes; blood on Venables' shoe was matched to that of Bulger through DNA tests.

The trial

In the initial aftermath of their arrest, and throughout the media accounts of their trial, the boys were referred to simply as 'Child A' (Thompson) and 'Child B' (Venables). At the close of the trial, the judge ruled that their names should be released (probably because of the widely publicized nature of the murder and the public reaction to it), and they were identified by name in the account of their convictions, along with lengthy descriptions of their lives and backgrounds. Public shock at the murder was compounded by the release, after the trial was over, of mug shots taken during initial questioning by police. The pictures showed a pair of frightened children, and many found it hard to believe such a crime had been perpetrated by two people so young.

Five hundred angry protesters gathered at South Sefton Magistrates Court during the boys' initial court appearances. The parents of the accused were moved to different parts of the country and had to assume new identities, following a series of death threats.

The full trial took place at Preston Crown Court, and was conducted as an adult trial would have been, with the accused sitting in the dock away from their parents, and with the judge and court officials dressed in full legal regalia. Each boy sat in full view of the court on raised chairs (so they could see out of the dock designed for adults) accompanied by two social workers. Although they were separated from their parents, they were within touching distance of them on days that their families attended the trial. News stories frequently reported on the demeanor of the defendants, since they were in full view of reporters. (These aspects of the trial were later criticized by the European Court of Human Rights, who ruled that they had not received a fair trial.)

The boys, who themselves did not testify in their own defense, were found guilty and sentenced to imprisonment at a young offenders institution at Her Majesty's Pleasure. The trial judge, Justice Morland, set their minimum period of incarceration to eight years. This was increased on appeal to ten years by the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Taylor of Gosforth and later to fifteen years by the Home Secretary, Michael Howard, on the grounds that he was 'acting in the public interest'. This decision was overturned in 1997 by the Law Lords. In October 2000, Lord Chief Justice Harry Woolf reduced their minimum sentence by two years for their behaviour in detention, effectively restoring the original trial judge's eight-year term.

Proposed causes

Social and family background

In court, details of the backgrounds of Thompson and Venables were not admitted. Thompson was one of the youngest of seven boys. His mother, a lone parent, was an alcoholic. His father, who left home when Thompson was five, was also a heavy drinker who beat and sexually abused his wife and children. Despite his quiet and friendly manner, Thompson came from a home in which it was normal practice for the older children to violently attack the younger ones, and Thompson was invariably on the receiving end.

Venables' parents were also separated. His brother and sister had educational problems and attended special needs schools, whilst his mother suffered psychiatric problems. Following his parents' separation, Venables became isolated and an attention-seeker. At school, he would regularly bang his head on walls. No effort was made to find the cause of his obvious distress.

Other media commentators blamed the behaviour of Venables and Thompson on their families, or on their social situation, living in one of the most deprived areas of the UK. The Liverpool Echo newspaper described the city, at the time of the murder, as 'a wounded city... The region's economy was on its knees, and unemployment was soaring'. A 2001 OFSTED report on Liverpool's schools said that 'the city of Liverpool has the highest degree of deprivation in the country'. Following the murder, the boys' mothers, Susan Venables and Ann Thompson, were repeatedly attacked in the street and vilified in the press.

Thompson's father had abandoned his wife and children five years previously, one week before the family home was burned down in a fire. Ann Thompson was a heavy drinker, who found it difficult to control her seven children. Notes (obtained by author Blake Morrison) from an NSPCC case conference on the family, described it as 'appalling'. The children 'bit, hammered, battered, {and} tortured each other'. Incidents in the report included Philip (the third child) threatening his older brother Ian with a knife. Ian asked to be taken into foster care, and when he was returned to his family, he attempted suicide with an overdose of painkillers. Both Ann and Philip had also attempted suicide in the past.

Venables' family was less chaotic; although his parents were also separated, they lived near each other, and he lived at his father's house two days a week. Both his older brother and younger sister had learning disabilities which were severe enough to make it necessary that they attend special schools for children too disabled to be taught in the mainstream system. Venables himself was hyperactive, and had attempted to strangle another boy with a ruler during a fight at school. The police had been called to Susan Venables's house in 1987, when she left her children (then aged 3, 5 and 7) alone in the house for three hours. Case notes from that incident describe Susan's 'severe depressive problem' and suicidal tendencies.

Video violence

One of the aspects of the case that gained much media attention was whether Venables and Thompson had been watching violent films in the days and months prior to the murder, and whether or not those movies had contributed to making the pair act in the way they did. The judge mentioned that one of their fathers possessed a large collection of violent videos, and that they probably had access to them whilst playing truant from school. As Bulger's death was similar to a death in the film Child's Play 3, and the father of one of the boys was known to have rented this film the week before the murder, The Sun newspaper explicitly named it as a movie they had seen, and printed a full front-page picture of the menacing Chucky, the child-killing doll of that horror series. However, no evidence that the boys had watched such movies was formally presented to the jury, but the case gave rise to a national debate about the acceptability of violent media. Although no films were subsequently banned by the British Board of Film Classification, several video rental chains voluntarily stopped stocking Child's Play 3 and other titles listed by The Sun.

In early 1994, Liberal Democrat David Alton MP, a long-time campaigner against violent movies, commissioned Professor Elizabeth Newson to report on Video Violence and the Protection of Children, as part of his case for an amendment to the forthcoming Criminal Justice Bill. Her report, which consisted primarily of a review of similar studies from around the world, stated that there was a strong link between video violence and real world violence, and that although correlation does not necessarily imply causation, she believed there was causation in this case. [1] The report's method came under fierce criticism from those opposed to Alton's amendment (for example, J. McGuigan's Culture and the Public Sphere, and the theories of David Gauntlett).

Multiple causes

Another report on children and video violence was published in 1998; it was commissioned by the Home Office in 1995 in response to fears raised by Bulger's murder. The authors, Dr Kevin Browne and Amanda Pennell of the University of Birmingham, emphasized the link between a violent home background and offending:

'Our research cannot prove whether video violence causes crime. But it does highlight the importance of family background and the offender's own personality, and thoughts in determining the effects of film violence.'

'The research points to a pathway from having a violent home background, to being an offender, to be being more likely to prefer violent films and violent actors. Distorted perceptions about violent behaviour, poor empathy for others, and low moral development, all enhance the adoption of violent behaviour and violent film preferences.' [2]

Appeal and release

In 1999, lawyers acting for Venables and Thompson appealed to the European Court of Human Rights on the grounds that the boys' trial had not been impartial, since they were too young to be able to follow the proceedings and understand the workings of an adult court. They also claimed that Howard's intervention led to a charged atmosphere, making a fair trial impossible. The Court found in the boys' favour.

The European Court case led to the new Lord Chief Justice, Lord Justice Woolf, reviewing the minimum sentence imposed. In October 2000, he recommended the tariff be reduced from ten to eight years, adding that young offenders' institutions were a 'corrosive atmosphere' for the juveniles.

In June 2001, after a six-month review of the case, the Parole Board ruled the boys were no longer a threat to public safety and were thus eligible for release now that the minimum tariff had expired. The Home Secretary, David Blunkett, approved the decision, and they were both released that summer. They will live out their lives on a 'life license', which allows for their immediate re-incarceration if they break the terms of their release, that is if they are seen to be a danger to the public.

An estimated total of £4 million was spent in helping Thompson and Venables rebuild their lives, upon their release from custody.

The Manchester Evening News provoked controversy by naming the secure institutions in which the pair were housed, in possible breach of the injunction against press publicity which had been renewed early in 2001. In December of that year, the paper was found guilty of contempt of court, fined £30,000, and ordered to pay costs of £120,000.

The injunction against the press reporting on the boys' whereabouts applies only in England and Wales, and newspapers in Scotland or other countries can legally publish such information. With easy cross-border communications due to the internet, many expected their identities and whereabouts to quickly become public knowledge. Indeed, in June 2001, Venables' mother was quoted by the News of the World as saying that she expected her son to be 'dead within four weeks' of release. Her lawyers lodged a formal complaint with the Press Complaints Commission saying that Mrs Venables had said no such thing. By that time, however, the phrase had been widely re-reported. As of 2007, no publication of vigilante action has come to pass. Despite this, Bulger's mother, Denise, told how in 2004 she received an anonymous tip-off that helped her locate Thompson. She said she saw him but was 'paralysed with hatred', and did not communicate with him in any way. There were however, some mysterious rumours that there were assassination plots against Venables and Thompson, but none of the ideas has yet been proven.

More than five years after their release, stories and rumours about Venables and Thompson continue to circulate. In January 2006, the Sunday Mirror newspaper reported that Robert Thompson had fathered a child with a girlfriend [3] who remained unaware of his past. The paper also reported that Thompson had taken heroin since his release, and had been accused of shoplifting, but that he now worked "in an office" and earned "a reasonable wage". In March 2006, however, it was reported in The Sun newspaper that Thompson was in a "settled relationship" with a gay male partner who was made fully aware of his conviction, and that he had been living with the man at a "secret address" in North West England for "several months" [4].

In May 2006 it was widely rumoured that Sean Walsh, sentenced to 15 years for attempting to kill his pregnant girlfriend and her three year old daughter, was Robert Thompson. Walsh had moved to Ireland in 2001, the year the Bulger killers were released, was known to have convictions as a Juvenile in the UK and had been in regular contact with the psychiatric services in Wigan (approximately 20 miles from Liverpool) from the age of 15. At one point Walsh claimed to be Thompson but the authorities dismissed this.[5] [6] [7]

In June 2006, a widely circulated e-mail message claimed that Dante Arthurs, a man accused of murdering a child in Perth, Western Australia, was in fact one of James Bulger's killers living under a new identity [8]. This claim has also been denied by authorities.

Similar events

References

- The Guardian (1993-2002) Special Report: The James Bulger Case, retrieved 23 April 2005.

- BBC News (24 June 2001) Bulger killers 'face danger', retrieved 23 April 2005.

- BBC News (22 June 2001) Bulger statement in full, retrieved 23 April 2005.

- ABC News (28 June 2006) Speculation that accused child rapist and murderer 'Dante Arthurs' may be Robert Thompson's assumed identity, retrieved 29 June 2006.

Video violence

- 'Ten things wrong with the media effects model' article by David Gauntlett

- The British Video Standards Commission's articles on video violence

- Response from the British Board of Film Classification to the 1998 Home Office study