List of inventors killed by their own invention

Appearance

(Redirected from List of inventors killed by their own inventions)

This is a list of people whose deaths were in some manner caused by or directly related to a product, process, procedure, or other technological innovation that they invented or designed.

Ill-fated inventors

Automotive

- Sylvester H. Roper (1823–1896), inventor of the Roper steam velocipede, died of a heart attack or subsequent crash during a public speed trial in 1896. It is unknown whether the crash caused the heart attack, or the heart attack caused the crash.[1]

- William Nelson (c. 1879–1903), a General Electric employee, invented a new way to motorize bicycles. He then fell off his prototype bike during a test run.[2]

- Francis Edgar Stanley (1849–1918) was killed while driving a Stanley Steamer automobile. He drove his car into a woodpile while attempting to avoid farm wagons travelling side by side on the road.[3]

- Fred Duesenberg (1876–1932) was killed in a high-speed road accident in a Duesenberg automobile.[4]

Aviation

- Ismail ibn Hammad al-Jawhari (died c. 1003–1010), a Kazakh Turkic scholar from Farab, attempted to fly using two wooden wings and a rope. He leapt from the roof of a mosque in Nishapur and fell to his death.[5]

- Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier (1754–1785) was the first known fatality in an air crash when his Rozière balloon crashed on 15 June 1785 while he and Pierre Romain attempted to cross the English Channel.

- Thomas Harris (d. 1824) invented the gas discharge valve, the first such device for emptying a lighter-than-air balloon of gas. He died when the cord attached to the gas discharge valve in his balloon tightened as it was deflated, releasing more gas than intended and crashing the balloon. [6]

- Robert Cocking (1776–1837) died when his homemade parachute failed. Cocking failed to include the weight of the parachute in his calculations.[7]

- Otto Lilienthal (1848–1896) died from injuries sustained in a crash of his hang glider.[8]

- Percy Pilcher (1867–1899) died after crashing his glider, having been prevented from demonstrating his powered aircraft.

- Franz Reichelt (1879–1912), a tailor, fell to his death from the first deck of the Eiffel Tower during the initial test of a coat parachute which he invented. Reichelt promised the authorities he would use a dummy, but instead he confidently strapped himself into the garment at the last moment and made his leap in front of a camera crew.[9]

- Aurel Vlaicu (1882–1913) died when his self-constructed airplane,[10] A Vlaicu II, failed during an attempt to cross the Carpathian Mountains.[11]

- Henry Smolinski (1933–1973) was killed during a test flight of the AVE Mizar, a flying car based on the Ford Pinto and the sole product of the company he founded.[12][13]

- Charles Ligeti (d. 1987) was killed in a crash in 1987 when testing modifications to his Ligeti Stratos aircraft of novel closed wing design.

- Michael Dacre (1956–2009) died after a crash that occurred while testing his flying taxi device.[14][15][16]

Chemistry

- Marie Curie (1867–1934) was a Polish-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity and is credited for discovering radioactive polonium. On 4 July 1934, she died at the Sancellemoz sanatorium in Passy, Haute-Savoie, from aplastic anaemia believed to have been contracted from her long-term exposure to radiation, some of which was from the devices she created.[17]

Industrial

- Carlisle Spedding (1695-1755);[18] mining engineer, inventor and colliery manager, who worked in mines owned by Sir James Lowther. Spedding, along with his elder brother James, introduced many improvements to the mining industry, especially relating to drainage and ventilation, which did much to improve safety for miners. In 1730[19], Spedding invented a mechanical device, consisting of a pair of geared wheels that forced a flint against a rotating steel disc, giving off a shower of sparks to provide some illumination. This, named the "Spedding Steel Mill"[20], was allegedly safer than the use of a naked flame, and until the invention of the Davy and Stephenson safety lamps many decades later, was widely used in mines. Carlisle Spedding was killed in an underground gas explosion on August 8th 1755 in Whitehaven, Cumbria, said to have been caused by one of his steel mills.

- William Bullock (1813–1867) invented the web rotary printing press.[21][22] Several years after its invention, his foot was crushed during the installation of a new machine in Philadelphia. The crushed foot developed gangrene and Bullock died during the amputation.[23]

- Dr. Sabin Arnold von Sochocky (1883–1928) was an inventor of the luminescent paint (used for clocks in early 20th century) based on radioactive radium (previously discovered by Pierre and Marie Curie). He was a founder of the United States Radium Corporation where some of its workers died from radium poisoning. His invention reportedly took his life, as well: he eventually died of aplastic anemia.[24][25]

Maritime

- Henry Winstanley (1644–1703) designed and built the world's first offshore lighthouse[26] on the Eddystone Rocks in Devon, England between 1696 and 1698. Boasting of the safety of his invention, he expressed a desire to shelter inside it "during the greatest storm there ever was".[27] During the Great Storm of 1703, the lighthouse was completely destroyed with Winstanley and five other men inside. No trace of them was found.[28]

- John Day (c. 1740–1774) was an English carpenter and wheelwright who died during a test of his experimental diving chamber.[29]

- Horace Lawson Hunley (1823–1863) was a Confederate American marine engineer who built the H. L. Hunley[30] submarine and perished inside it as a member of the second crew to face drownings while testing the experimental vessel. After Hunley's death, the Confederates resurfaced the ship for another mission that proved fatal for its own crew: the successful sinking of the USS Housatonic during the American Civil War. The feat made the H. L. Hunley the first submarine to sink an enemy warship in wartime.

- Karl Flach (1821–1866) was a German living in Valparaiso, Chile. He built the submarine Flach (brother of the Peruvian "Toro", sunk, refloated by the Chilean Navy and then disappeared, both events in the Saltpeter War) at the request of the Chilean government, in response to the bombing of Valparaíso. He died after the submarine failed to rise, along with his son and other sailors.

- Julius H. Kroehl (1820–1867), a German-American inventor and former Union Navy contractor, is thought to have died of decompression sickness after experimental dives with the Sub Marine Explorer, which he co-designed and constructed with his business partner Ariel Patterson.[31]

- Cowper Phipps Coles (1819–1870) was a Royal Navy captain who drowned with approximately 480 others in the sinking of HMS Captain, a masted turret ship of his own design.[32]

- William Pitt (1841–1909) was a Canadian ferryman who designed the underwater cable ferry as means of improving the former ferry used to connect the Kingston Peninsula to the Kennebecasis Valley in New Brunswick. In 1909, Pitt died after sustaining injuries caused by falling into his ferries' machinery.[33]

- Thomas Andrews (1873–1912), the naval architect of the Titanic, designed his famous vessel while serving as the managing director and head of the drafting department of the shipbuilding company Harland and Wolff in Belfast, Ireland. He was aboard the Titanic during her maiden voyage and perished alongside approximately 1,500 others when the ship hit an iceberg and sank on 14 April 1912. Andrews' body was never recovered.

- Stockton Rush (1962–2023) was a pilot, engineer, and businessman who oversaw the design and construction of the OceanGate submersible Titan, used to take tourists to view the wreck of the Titanic. On 18 June 2023, the craft imploded during a dive to the Titanic, killing Rush and four other passengers.[34] Rush had spent years staunchly defending his unregulated design, claiming that "at some point, safety is just pure waste. I mean, if you just want to be safe, don't get out of bed, don't get in your car, don't do anything".[35]

Medical

- Alexander Bogdanov (1873–1928) was a Russian polymath, Bolshevik revolutionary and pioneer haemotologist who founded the first Institute of Blood Transfusion in 1926. He died from acute hemolytic transfusion reaction after carrying out an experimental mutual blood transfusion between himself and a 21-year-old student with an inactive case of tuberculosis. Bogdanov's hypotheses were that the younger man's blood would rejuvenate his own aging body, and that his own blood, which he believed was resistant to tuberculosis, would treat the student's disease.[36][37]

- Thomas Midgley Jr. (1889–1944) was an American engineer and chemist who contracted polio at age 51, leaving him severely disabled. He devised an elaborate system of ropes and pulleys to help others lift him from bed. He became entangled in the ropes and died of strangulation at the age of 55. However, he is better known for two of his other inventions: the tetraethyl lead (TEL) additive to gasoline, and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).[38][39][40]

Physics

- Georg Wilhelm Richmann (1711–1753) built an apparatus to study electricity from lightning. While "trying to quantify the response of an insulated rod to a nearby storm," it produced a ball of lightning that struck him in the forehead and killed him.[41]

Publicity and entertainment

- Karel Soucek (1947–1985) was a Czech professional stuntman living in Canada who developed a shock-absorbent barrel. He died following a demonstration involving the barrel being dropped from the roof of the Houston Astrodome. He was fatally injured when his barrel hit the rim of the water tank meant to cushion his fall.[42]

Railway

- Webster Wagner (1817–1882) died in a train accident, crushed between two of the railway sleeper cars he had invented.[43]

- Henri Thuile (died 1900), inventor of the large high-speed Thuile steam locomotive, died during a test run between Chartres and Orléans. Conflicting accounts indicate that he was either thrown from the derailing locomotive, hitting a telegraph pole,[44] or that he simply leaned too much and was instantly killed by hitting his head against a piece of bridge scaffolding.[45]

- Valerian Abakovsky (1895–1921) constructed the Aerowagon, an experimental high-speed railcar fitted with an aircraft engine and propeller traction, intended to carry Soviet officials. On 24 July 1921, it derailed at high speed, killing 7 of the 22 on board, including Abakovsky.[46]

Rocketry

- Max Valier (1895–1930) invented liquid-fuelled rocket engines as a member of the 1920s German rocket society Verein für Raumschiffahrt. On 17 May 1930, an alcohol-fuelled engine exploded on his test bench in Berlin, killing him instantly.[47]

- Mike Hughes (1956–2020) was killed when the parachute failed to deploy during a crash landing while piloting his homemade steam-powered rocket.[48]

Popular legends and related stories

- In Greek mythology, Daedalus built wings made of feathers and blankets to escape the labyrinth of Crete with his son Icarus, who died while ignoring his father's instructions not to "fly too close to the sun".

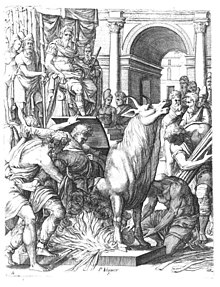

- Perillos of Athens (c. 550 BCE), according to legend, was the first to be roasted in the brazen bull he made for Phalaris of Sicily for executing criminals.[49][50]

- Li Si (208 BCE), Prime Minister during the Qin dynasty, was executed by the Five Pains method which some sources claim he had devised.[51][52][53][failed verification] However, the history of the Five Pains is traced further back in time than Li Si.

- Wan Hu, a possibly apocryphal[54] 16th-century Chinese official, is said to have attempted to launch himself into outer space in a chair to which 47 rockets were attached. The rockets exploded, and it is said that neither he nor the chair were ever seen again.

- João Torto, a most likely apocryphal 16th-century Portuguese man who jumped from the top of Viseu Cathedral wearing a biplane-like flying rig and an eagle-shaped helmet.[55]

- Orban, the designer and manufacturer of the Basilic, a gigantic cannon used to break down the walls of Constantinople in 1453, died when one of his cannons exploded in battle.[56]

- William Brodie, "Deacon Brodie" of 18th-century Edinburgh, is reputed to have been the first victim of a new type of gallows of which he was also the designer and builder, but this is doubtful.[57]

- In The Adventures of Philip by William Makepeace Thackeray, the narrator, Pendennis, asks "Was not the good Dr Guillotin executed by his own neat invention?" In fact, Joseph-Ignace Guillotin was neither the inventor of the guillotine nor executed by it.

- Jimi Heselden (1948–2010) was killed while riding a Segway scooter. While he owned the company Segway Inc., he did not invent the Segway.[58]

See also

- Darwin Awards – Rhetorical tongue-in-cheek award

- List of entertainers who died during a performance

- List of unusual deaths

- Hoist with his own petard – Quote from Hamlet indicating an ironic reversal

References

- ^ "Died in the Saddle", Boston Daily Globe, p. 1, 2 June 1896

- ^ "Killed By Own Invention – While Trying Motor Bicycle He Had Made, Schenectady Man Meets Death". The New York Times. 4 October 1903. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Doris A. Isaacson, ed. (1970). Maine: A Guide "Down East" (2nd ed.). Rockland, Maine: Courier-Gazette, Inc. p. 386. (First edition).

- ^ "F. S. Duesenberg Dies of Auto Injury". The New York Times. 27 July 1932. p. 17.

- ^ Boitani, Piero (2007). Winged words: flight in poetry and history. University of Chicago Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-226-06561-8. Retrieved 22 November 2014 – via Google Books.

- ^ "1824 DEATH OF LIEUT. THOMAS HARRIS AT BEDDINGTON PARK, CROYDON". The Aeronautical Journal. 33. Royal Aeronautical Society. 1929.

Thomas Harris was the first English aeronaut killed during a flight in a balloon. His death was due to his own invention of a patent valve...

- ^ [1] Science and Society

- ^ Biography of Otto Lilienthal Lilienthal Museum

- ^ 2003 Personal Accounts Darwin Awards

- ^ Great Britain Patent GB191026658

- ^ Ralph S. Cooper, D.V.M. "Aurel Vlaicu at www.earlyaviators.com". Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Morris, Neil (2010). From Fail to Win, Learning from Bad Ideas: Transportation. Heinemann-Raintree Library. ISBN 978-1-4109-3911-1.

- ^ Soniak, Matt, "The Flying Pinto That Killed Its Inventor", Mental Floss, July 30, 2012 Accessed 26 April 2023

- ^ "British inventor dies in crash on test flight of his flying taxi". The Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 20 August 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ "Michael Robert Dacre". memorialwebsites.legacy.com. Archived from the original on 2023-04-30. Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ Franco, Michael, "Death by Invention: 5 Inventors who Died by Their Own Work", How Stuff Works? Accessed 26 April 2023

- ^ "Marie Curie". www.mariecurie.org.uk. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Beckett, J V (1983). "Carlisle Spedding ( 1695 -1 755), Engineer, Inventor and Architect" (PDF). Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society. Second Series. 83: 131–140. doi:10.5284/1061803.

- ^ "Safety lamp - First attempts at safe lamps". Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ "The Carlisle Spedding Steel Mill" (PDF). Retrieved 19 December 2024.

- ^ "United States Patent 61996". Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ "United States Patent 100,367". Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ "Inventors killed by their own inventions". Discovery News. Retrieved 2010-10-30.

- ^ "RADIUM PAINT TAKES ITS INVENTOR'S LIFE; Dr. Sabin A. von Sochocky Ill a Long Time, Poisoned by Watch Dial Luminant. 13 BLOOD TRANSFUSIONS Death Due to Aplastic Anemia-- Women Workers Who Were Stricken Sued Company". The New York Times. 1928-11-15. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ "Sabin Arnold von Sochocky". geni_family_tree. 1883. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ Clingan, Ian C., lighthouse (coastal navigation), Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved 2 July 2023

- ^ Hart-Davis, Adam (2002). Henry Winstanley and the Eddystone Lighthouse. Thrupp, Gloucestershire: Sutton Company Limited. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-7509-1835-0.

- ^ "Eddystone Lighthouse History". Eddystone Tatler Ltd. Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2006.

- ^ Churchill, Dennis (2011). "The First Submariner Casualty" (PDF). In Depth (32): 5–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ "Sub Marine Explorer". Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 2010. Retrieved 2021-03-31.

- ^ Sandler, Stanley (2004). Battleships: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-85109-410-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wright, Julia (12 October 2023). "Ferry tale: How cable ferries became a way of life in southern N.B." CBC News. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Perrottet, Tony. "A Deep Dive Into the Plans to Take Tourists to the 'Titanic'". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ McShane, Asher. ""Safety is just pure waste": Lost Titanic sub's creator made chilling comment in 2022 interview as search becomes "bleak"". LBC. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ Huestis, Douglas W. (October 2007). "Alexander Bogdanov: The Forgotten Pioneer of Blood Transfusion". Transfusion Medicine Reviews. 21 (4): 337–340. doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2007.05.008. PMID 17900494. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ Krementsov, Nikolai (2011). A Martian Stranded on Earth: Alexander Bogdanov, Blood Transfusions, and Proletarian Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0-226-45412-2.

- ^ Bryson, Bill. A Short History of Nearly Everything. (2003) Broadway Books, US. ISBN 0-385-66004-9

- ^ Alan Bellows (2007-12-08). "The Ethyl-Poisoned Earth". Damn Interesting.

- ^ "Milestones, Nov. 13, 1944" Time, November 13, 1944

- ^ Franklin, Benjamin (1962). "Account of the Death of Georg Richmann". The Papers of Benjamin Franklin. Yale University Press. pp. 219–221. ISBN 9780300006544.

- ^ "35,000 Watch as Barrel Misses Water Tank: 180-Ft. Drop Ends in Stunt Man's Death". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 21 January 1985. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ "Meeting a Terrible Fate – Nine Persons Crushed and Burned in a Collision – A Train Crashing Into the Rear of the Atlantic Express – Nine, Perhaps Twelve, Victims Caught in the Burning Cars – State Senator Wagner Among the Dead – Narrow Escape of Many Others – Terrible Scene at the Wreck". New York Times. January 14, 1882. p. 1. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ Douglas Self. "The Thuile Cabforward". Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ DH. "La locomotive Thuile Cabforward". Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ Alexey Abramov / Алексей Абрамов By the Kremlin Wall / У кремлёвской стены Moscow / М., Politizdat / Политиздат 1978 pp./стр. 399 (in Russian)

- ^ "American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics". Archived from the original on 26 December 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Silverman, Hollie (February 23, 2020). "Daredevil 'Mad Mike' Hughes dies while attempting to launch a homemade rocket". CNN. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ "Perillos of the Brazen Bull". Archived from the original on 16 December 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ "The Brazen Bull". Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ Guisso, R. W. L., The first emperor of China, New York : Birch Lane Press, 1989. ISBN 1-55972-016-6. Cf. p.37

- ^ Fu, Zhengyuan, Autocratic tradition and Chinese politics, Cambridge University Press, 1993. Cf. p.126

- ^ "The Civilization of China, Chapter II: Law and Government". Archived from the original on 11 August 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ^ Williamson, Mark (2006). Spacecraft Technology: The Early Years. IET. ISBN 978-0-86341-553-1.

- ^ Maia, Samuel (1933). "O primeiro aviador português: quem foi?" [The first Portuguese aviator: who was he?] (PDF). Arquivo Nacional (in Portuguese): 822–823, 831. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Schmidtchen, Volker (1977b), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte, 44 (3): 213–237

- ^ Roughead, William (1951). Classic Crimes: A Selection from the Works of William Roughead. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-394-71648-5.

- ^ "Segway company owner rides scooter off cliff, dies". NBC News. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

A British businessman, who bought the Segway company less than a year ago, died after riding one of the scooters off a cliff and into a river near his Yorkshire estate.

Further reading

- E. Cobham Brewer (1898). "Inventors Punished by their own inventions". Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. Bartleby. pp. 657–658.