Swedish literature

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Sweden |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

Swedish literature (Swedish: Svensk litteratur) is the literature written in the Swedish language or by writers from Sweden.[1]

The first literary text from Sweden is the Rök runestone, carved during the Viking Age circa 800 AD. With the conversion of the land to Christianity around 1100 AD, Sweden entered the Middle Ages, during which monastic writers preferred to use Latin. Therefore, there are only a few texts in the Old Swedish from that period. Swedish literature only flourished after the Swedish literary language was developed in the 16th century, which was largely due to the full translation of the Christian Bible into Swedish in 1541. This translation is the so-called Gustav Vasa Bible.

With improved education and the freedom brought by secularisation, the 17th century saw several notable authors develop the Swedish language further. Some key figures include Georg Stiernhielm (17th century), who was the first to write classical poetry in Swedish; Johan Henric Kellgren (18th century), the first to write fluent Swedish prose; Carl Michael Bellman (late 18th century), the first writer of burlesque ballads; and August Strindberg (late 19th century), a socio-realistic writer and playwright who won worldwide fame. In Sweden, the period starting in 1880 is known as realism because the writing had a strong focus on social realism.

In the 1900s, one of the earliest novelists was Hjalmar Söderberg. The early 20th century continued to produce notable authors, such as Selma Lagerlöf (Nobel laureate 1909) and Pär Lagerkvist (Nobel laureate 1951). A well-known proletarian writer who gained fame after World War I was Vilhelm Moberg; between 1949 and 1959, he wrote the four-book series The Emigrants (Swedish: Utvandrarna), often considered one of the best literary works from Sweden. In the 1960s, Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö collaborated to produce a series of internationally acclaimed detective novels. The most successful writer of detective novels is Henning Mankell, whose works have been translated into 37 languages. In the spy fiction genre, the most successful writer is Jan Guillou.

In recent decades, a handful of Swedish writers have established themselves internationally, such as the detective novelist Henning Mankell and thriller writer Stieg Larsson. Also well known outside of Sweden is the children's book writer Astrid Lindgren, author of works such as Pippi Longstocking and Emil of Maple Hills.

There is also a strong tradition of Swedish as the literary language of the Finnish nobility; after the separation in the start of the 19th century, Finland has produced Swedish-language writers such as Johan Ludvig Runeberg, who wrote the Finnish national epic The Tales of Ensign Stål, and Tove Jansson.

Old Norse

[edit]

Most runestones had a practical, rather than a literary, purpose and are therefore mainly of interest to historians and philologists. Several runic inscriptions are also nonsensical by nature, being used for magical or incantatory purposes. The most notable literary exception is the Rök runestone from circa 800 AD. It contains the longest known inscription, and encompasses several different passages from sagas and legends, in various prosodic forms. Part of it is written in alliterative verse, or fornyrdislag. It is generally regarded as the beginning of Swedish literature.[2][3]

Middle Ages

[edit]The Christianization of Sweden was one of the main events in the country's history, and it naturally had an equally profound impact on literature.

The Gök runestone is a case in point of how the older literature dissolved. It uses the same imagery as the Ramsund carving, but a Christian cross has been added and the images are combined in a way that completely distorts the internal logic of events.[4] Whatever the reason may have been, the Gök stone illustrates how the pagan heroic mythos was going towards its dissolution, during the introduction of Christianity.[4]

Literature now looked to foreign texts to provide models. By 1200, Christianity was firmly established and a Medieval European culture appeared in Sweden. Only a selected few mastered the written language, but little was written down. The earliest works written in Swedish were provincial laws, first written down in the 13th century.

Most education was provided by the Catholic Church, and therefore the literature from this period is mainly of a theological or clerical nature. The majority of other literature written consists of law texts. An exception to this are the rhyming chronicles, written in knittelvers.

16th and 17th century

[edit]Reformation literature

[edit]| Reformation-era literature |

|---|

Swedish Reformation literature is considered to have been written between 1526 and 1658. However, this period has not been highly regarded from a literary point of view. It is generally considered a step back in terms of literary development.[5][6][7] The main reason was King Gustav Vasa's wish to control and censor all publications, with the result that only the Bible and a few other religious works were published.[8] At the same time, Catholic monasteries were plundered and Catholic books were burnt. The king did not consider it important to reestablish higher education, so Uppsala University was left to decay.[9]

There were comparatively few groups of writers during this time. The burghers still had little influence, while the Church clerics had had their importance severely reduced. The Protestant Reformation of the 1520s left priests with a fraction of their previous political and economic power. Those Swedes who wanted higher education usually had to travel abroad to the universities of Rostock or Wittenberg.[10]

Apart from Christian Reformation literature there was one other significant ideological movement. This was Gothicismus, which glorified Sweden's ancient history.[10]

While contributions to Swedish culture were sparse, this period did at least provide an invaluable basis for future development. Most importantly, the Swedish Bible translation of 1541, the so-called Gustav Vasa Bible, gave Sweden a uniform language for the first time. Secondly, the introduction of the printing press resulted in literature being spread to groups it had previously been unable to reach.[10]

Renaissance literature

[edit]

The period in Swedish history between 1630 and 1718 is known as the Swedish Empire. It partly corresponds to an independent literary period. The literature of the Swedish Empire era is regarded as the beginning of the Swedish literary tradition.[11]

Renaissance literature is considered to have been written between 1658 and 1732. It was in 1658 that Georg Stiernhielm published his Herculus, the first hexametrical poem in the Swedish language.

When Sweden became a great power, a stronger middle class culture arose. Unlike the age of the Reformation, education was no longer solely a matter of ecclesiastical studies such as theology. During this era, there was a wealth of influences from the leading countries of the time, namely Germany, France, Holland and Italy. It was symptomatic that the man who came to be known as Sweden's first poet, Georg Stiernhielm, was more acquainted with Ancient philosophy than with Christian teachings.

Gothicismus also gained in strength. During the Swedish Empire period, it developed into a literary paradigm, the purpose of which was to foster the idea that Sweden was a natural great power.[10]

18th century

[edit]

The 18th century has been described as the Swedish Golden Age in literature and science. During this period, Sweden produced authors and literature of a much higher standard than ever before. One key factor was the political period known as the Age of Liberty (1712–1772), and the first Swedish freedom of the press act written in 1766 (see Constitution of Sweden). It meant the ultimate breakthrough of secular literature.[12][13]

Naturally, the impulses that invigorated Swedish cultural life had their origin in the European Age of Enlightenment. The main influences came from Germany, England and France, and these were reflected in Swedish literature. The Swedish language became enriched by French words, and ideas of liberalization were based on the English model.[14]

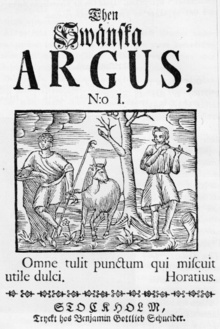

Swedish literature consolidated around 1750; this is considered the start of a linguistic period called Late Modern Swedish (1750 – circa 1880). The first great works of the age were those of Olov von Dalin (1708–1763), and in particular his weekly Then Swänska Argus, based on Joseph Addison's The Spectator. Dalin gave a sketch of Swedish culture and history using language which had an unprecedented richness of sarcasm and irony. In the 1730s and 1740s, Dalin was unrivalled as the brightest star in the Swedish literary sky. He was the first to refine the language for practical purposes, in comparison with the laboured poetry of the 17th century, and he was the first author to be read and appreciated by the general public.[15][16]

In the 18th century, Latin rapidly declined in popularity in favour of the national language. One of the first authors to aim his books directly at the general public was the world-renowned botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778). Later key figures included the poets Johan Henrik Kellgren (1751–1795) and Carl Michael Bellman (1740–1795).

The 18th century was also the century when female writers first gained widespread recognition. Sophia Elisabet Brenner (1659–1730), Sweden's first professional female writer, had started her career in the 17th century, but it continued into the following century.[17] Later, Anna Maria Lenngren's (1754–1817) often satirical writings proved to have lasting influence, and it remains a point of debate to this day how exactly to interpret "Några ord till min k. Dotter, i fall jag hade någon" ('A few words for my beloved daughter, if I had had one') – are the exhortations to remain at home and not get involved in literature or politics serious or satirical?[18]

19th century

[edit]Romanticism

[edit]

In European history, the period circa 1805–1840 is known as Romanticism. It also made a strong impression on Sweden, due to German influences. During this relatively short period, there were so many great Swedish poets that the era is referred to as the Golden Age of Swedish poetry.[19][20] The period started around 1810 when several periodicals were published which rejected the literature of the 18th century. An important society was the Gothic Society (1811), and their periodical Iduna, a romanticised look back towards Gothicismus.[19]

One significant reason was that several poets for the first time worked towards a common direction. Four of the main romantic poets who made significant contributions to the movement were: the professor of history Erik Gustaf Geijer, the loner Erik Johan Stagnelius, the professor of Greek language Esaias Tegnér and the professor of aesthetics and philosophy P.D.A. Atterbom.[21]

Early liberalism

[edit]The period between 1835 and 1879 is known as the early liberal period in Swedish history. The views of the Romantics had come to be perceived by many as inflated and overburdened by formality. The first outspoken liberal newspaper in Sweden, Aftonbladet, was founded in 1830. It quickly became the leading newspaper in Sweden because of its liberal views and criticism of the current state of affairs. The newspaper played its part in turning literature in a more realistic direction, because of its more concise use of language.[22][23]

Several authorities would regard Carl Jonas Love Almqvist (1793–1866) as the most outstanding genius of the 19th century in Sweden.[24] Beginning in 1838, he published a series of socially and politically radical stories attacking both marriage and clerical institutions. Several of his ideas are still interesting for modern readers, in particular the work Det går an (1839) which reached the German bestseller list as late as 2004.[25][26]

Naturalism, or realism

[edit]

Naturalism is one name for the literary period between 1880 and 1900. In Sweden, however, the period starting in 1880 is known as realism. This is partly because the 1880s had such a strong focus on social realism, and partly because the 1890s was a period of its own, the "90s poets".[27]

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Scandinavian literature made its first impression on world literature. From Sweden, the main name was August Strindberg, but Ola Hansson, Selma Lagerlöf and Victoria Benedictsson also attained wider recognition.[28]

The breakthrough of realism in Sweden occurred in 1879. That year, August Strindberg (1845–1912) published The Red Room (Röda Rummet), a satirical novel that relentlessly attacked the political, the academic, the philosophical and the religious worlds.[29][30]

August Strindberg was a writer world-famous for his dramas and prose, noted for his exceptional talent and complex intellect. He would continue to write several books and dramas until his death in Stockholm.[29][30] He also was an accomplished painter and photographer.[31]

The 90s poets

[edit]The Swedish 1890s is noted for its poetic neo-romanticism, a reaction to the socio-realistic literature of the 1880s. The first key literary figure to emerge was Verner von Heidenstam (1859–1940); his literary debut came in 1887 with the collection of poetry Vallfart och vandringsår (Pilgrimage and Wander-Years).[32][33] A few years later, Gustav Fröding made his debut. While controversial in his own time, Fröding has proven to be Sweden's most popular poet.[34] The poetry of Erik Axel Karlfeldt was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1931.

The novelist Selma Lagerlöf (1858–1940) was arguably the brightest star of the 1890s, and her influence has lasted up to modern times. Two of her major works, which have been translated into several languages, are The Wonderful Adventures of Nils (1906–1907) and Gösta Berlings saga (1891), but she also wrote several other highly regarded books. Lagerlöf was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1909, mainly for her storytelling abilities.[35][36]

20th century

[edit]It was in the 1910s that a new literary period began with the ageing August Strindberg, who published several critical articles, contesting many conservative values. With the advent of social democracy and large-scale strikes, the winds were blowing in the direction of social reforms.[37][38]

The modern novel

[edit]

In the 1910s, the dominant form of literary expression was now the novel. One of the earliest novelists was Hjalmar Söderberg (1869–1941). Söderberg wrote in a somewhat cynical way, at times with Nietzschean overtones, disillusionment and pessimism. In 1901 he published Martin Birck's Youth. It was appreciated by many for its literary qualities, but an even greater aspect was its depiction of Stockholm, which is widely regarded as the best portrait of Stockholm ever written.[39] His most highly regarded work was yet to come however: Doctor Glas (1905), a tale of vengeance and passion, viewed by some as the best and most complete of all Swedish novels.[40] Margaret Atwood, for example, has said of Doctor Glas: "It occurs on the cusp of the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, but it opens doors the novel has been opening ever since".[41] Söderberg's 1912 novel Den allvarsamma leken (The Serious Game) is also acknowledged as a classic in Swedish literature and is still widely read. It has been called the only romance novel of any worth in Swedish literature and has been translated to at least fourteen different languages.[42][43]

Contemporary to Söderberg was Bo Bergman. Further development of the novel is associated with writers such as Gustaf Hellström, Sigfrid Siwertz, Elin Wägner and Hjalmar Bergman.[44]

Modernism

[edit]Pär Lagerkvist was one of the first modernists in Sweden. His expressionistic poem Ångest (Anguish, 1916) introduced modernist literature in Sweden. Lagerkvist also wrote prose and plays in works that addressed the great existential questions. In 1951 Lagerkvist was awarded The Nobel Prize in Literature.[45]

Another early modernist was Birger Sjöberg whose controversial expressionistic book of poems Kriser och kransar (Crises and Wreaths) appeared in 1926. The anxiety-ridden poems was an unexpected contrast to Sjöberg's earlier success with the idyllic and popular Fridas visor (1922). Both Lagerkvist and Sjöberg had an influence on the modernist poets of the 1930s and 1940s.[45]

Karin Boye was influenced by modernism and psychoanalysis. Boye is one of the most widely read poets in Sweden and is also known for the dystopic novel Kallocain (1940).[45]

Proletarian literature

[edit]In 1929 Artur Lundkvist, Harry Martinson, Erik Asklund, Josef Kjellgren and Gustav Sandgren published the highly influential modernist poetry anthology Fem unga (Five Young Men).[45]

Swedish agriculture had a system with labourers called statare, who were paid in kind only, with product and housing, comparable with the Anglo-Saxon truck system. Among the few people with this background who made an intellectual career were the writers Ivar Lo-Johansson, Moa Martinson and Jan Fridegård. Their works were important to the abolition of the system.

With works such as the novel Godnatt, jord (Goodnight, earth, 1933) that portrayed statare, Ivar Lo-Johansson became a dominating figure in Swedish proletarian literature. Moa Martinson's novels focused on poor women farm laborers and factory workers. An autobiographical novel series beginning with Mor gifter sig (My mother gets married, 1936) is widely read.[45]

Eyvind Johnson and Harry Martinson developed the Swedish autobiograpichal novel with works such as Johnson's novel series Romanen om Olof (1934–1937) and Martinson's Flowering Nettles (1935). Johnson also took a stand against nazism in his novel trilogy Krilon (1941–1943) and wrote acclaimed historical novels. Martinson became known as one of Sweden's finest nature poets and in 1956 he published his poetic space epic Aniara.[45] In 1974 Johnson and Martinson shared the Nobel Prize in Literature.

A well-known proletarian writer was Vilhelm Moberg (1898–1973). He usually wrote about the lives of ordinary people and in particular the peasant population. Moberg's monumental work was published shortly after the Second World War: the four-volume The Emigrants series (1949–1959), about the Swedish emigration to North America. In this work, Moberg sentimentally depicted a 19th-century couple during their move to the New World; and the many struggles and difficulties they had to endure.[46]

Bourgeois literature

[edit]Bourgeois literature in the 1930s was written by Agnes von Krusenstjerna, Olle Hedberg and Fritiof Nilsson Piraten. Krusenstjernas portrayal of her class in the Von Pahlen-series (1930–1935) resulted in a furious debate. Notable poets of the era was Johannes Edfelt, Hjalmar Gullberg and Nils Ferlin.[45]

The 1940s and 1950s

[edit]In the 1940s modernist literature known as fyrtiotalism was typically pessimistic with recurring themes like anguish and guilt and the works became increasingly experimental. Stig Dagerman and novelist Lars Ahlin are the best known prose writers of this era while Erik Lindegren and Karl Vennberg were the leading poets.[45] Some acclaimed female authors such as Stina Aronson, Ulla Isaksson and the poet Elsa Grave also appeared in the 1940s.[45]

The literature of the 1950s continued some of the themes of the 1940s but became more ironic and playful with writers such as Lars Gyllensten, Willy Kyrklund and Lars Forssell. Birgitta Trotzig, a major modernist writer whose work focus on existential questions of a religions nature made her breakthrough with De utsatta (The Exposed) in 1957. Poets associated with the 1950s are Werner Aspenström who became one of the most widely read poets in Sweden and the highly influential Tomas Tranströmer who made his debut in 1954 with 17 dikter (17 Poems).[45]

The 1960s and 1970s

[edit]In the 1960s a new socially critical literature emerged that often focused on global perspective and anti-war themes. Journalistic documentary books was a significant literary trend with writers such as Jan Myrdal, Sven Lindqvist and Per Wästberg. Sara Lidman, a celebrated novelist of the 1950s also turned to such political writing in the 1960s, but later returned to writing novels centred on life in a small village in northern Sweden. Authors such as Per Olof Sundman and Per Olov Enquist turned to pseudo-documentary novels. Enquist later had international success with the historical novel Livläkarens besök (1999, The Visit of the Royal Physician). Lars Gustafsson, best known for his partially autobiographical novel series Sprickorna i muren (1971–78; "The Cracks in the Wall"), railed against the bureaucratic Swedish welfare state in multilayered, often metafictional novels. P. C. Jersild mixed social realism with the fantastic. Sven Delblanc wrote a series of four acclaimed historical novels about his childhood region, depicting the rural Swedish society in an unidealized way. Per Anders Fogelström had huge success with a series of widely read historical novels that followed a working-class family in Stockholm from the 1860s to the 1960s, beginning with Mina drömmars stad (City of My Dreams, 1960).[45]

Late 20th century

[edit]Göran Tunström's novels marked a return of the joy of storytelling after the political themes of the 1970s. His novels, rich of fantasy and humour and set in his home region Värmland, reached a highpoint with Juloratoriet (1983; The Christmas Oratorio). Torgny Lindgren is one of the internationally most successful Swedish writers. His novels, set in the remote countryside of northern Sweden often deals with questions of power, oppression, and the nature of evil, such as Ormens väg på hälleberget (1982; The Way of a Serpent). Another leading novelist of the 1970s to the 1990s was Kerstin Ekman.[47]

Lars Norén who had debuted as a poet in the 1960s emerged as a celebrated dramatist. Stig Larsson was the leading postmodern writer. Kristina Lugn was an acclaimed poet and dramatist. Katarina Frostenson, Ann Jäderlund and Birgitta Lillpers revitalized poetry.[45]

Klas Östergren had a major breakthrough with the novel Gentlemen in 1980. A prolific author of epic novels as well as short stories Östergren became regarded as one of the leading writers.[48] Majgull Axelsson was noted for the novel Aprilhäxan (April Witch, 1997) that mixed social realism with magic realism. Autobiographical and confessional writing had an upswing with writers such as Agneta Pleijel, Ernst Brunner and Carina Rydberg. Peter Kihlgård, Sigrid Combüchen and Inger Edelfeldt appeared as other prolific prose writers.[45]

Poetry

[edit]

In the 1930s and 1940s, poetry was influenced by the ideals of modernism. Distinguishing features included the desire to experiment, and to try a variety of styles, usually free verse without rhyme or metre.

The leading modernist figure soon turned out to be Hjalmar Gullberg (1898–1961). He wrote many mystical and Christian-influenced collections, such as Andliga övningar (Spiritual Exercises, 1932) and others. After a poetical break 1942–1952, he resurfaced with a new style in the 1950s. Atheistic on the surface, it was influential for the younger generation.[49][50]

Gunnar Ekelöf (1907–1968) has been described as Sweden's first surrealistic poet, due to his first poetry collection, the nihilistic Sent på jorden (1932), a work hardly understood by his contemporaries.[51] But Ekelöf moved towards romanticism and with his second poetry collection Dedikationen in 1934 he became appreciated in wider circles.[51] He continued to write until his old age, and was to attain a dominant position in Swedish poetry. His style has been described as heavy with symbolism and enigmatic, while at the same time tormented and ironical.[52]

Another important modernist poet was Harry Martinson (1904–1978). Harry Martinson had an unparalleled feeling for nature, in the spirit of Linnaeus. As was typical for his generation, he wrote free verse, not bound by rhyme or syllable-count. He also wrote novels, a classic work being the partly autobiographical Flowering Nettles, in 1935. His most remarkable work was, however, Aniara, 1956, a story of a spaceship drifting through space.[53]

Arguably the most famous Swedish poet of the 20th century is Tomas Tranströmer (1931–2015). His poetry is distinguished by a Christian mysticism, moving on the verge between dream and reality, the physical and the metaphysical.[54] At the same time there in the Sixties developed a strong tradition influenced by the historical avant-garde, and the Swedish movement of concrete poetry became one of the three global representants for experimental poetry at this time, with representatives like Öyvind Fahlström (who seemingly published the first manifesto for concrete poetry in the world 1954: "Hätila ragulpr på fåtskliaben"),[55] Åke Hodell, Bengt Emil Johnson, and Leif Nylén. In a reaction against the experimental Sixties one in the Seventies took up the beat-tradition from the US, in a continued avant-garde effort which resulted in little magazines publishing poetry, a stencil movement out of which one of Swedish main poets of today – Bruno K. Öijer – grow, and developed a lyrical performance with inspiration from Antonin Artaud's "Theatre of cruelty", rock'n'roll and the avant-garde performance.[56]

Dan Andersson (born 6 April 1888 in Skattlösberg, Grangärde parish (in present-day Ludvika Municipality), Dalarna, Sweden, died 16 September 1920 in Stockholm) was a Swedish author and poet. He also set some of his own poems to music. Andersson married primary school teacher Olga Turesson, the sister of artist Gunnar Turesson, in 1918. A nom de plume he sometimes used was Black Jim. Andersson is counted among the Swedish proletarian authors, but his works are not limited to that genre.[57]

Drama

[edit]Several writers of drama surfaced after World War II. In the 1950s, revues were popular; some names of the era were the comedians Povel Ramel and Kar de Mumma. The Hasse & Tage duo continued the comedic tradition in 1962 and became something of an institution in the Swedish revue world for twenty years, encompassing radio, television and film productions.

With the late 1960s came a breakthrough for alternative drama of a freer nature, and theatre became more of a venue for popular tastes. In the 1970s and 1980s, the two most noted playwrights were Lars Norén (1944–) and Per Olov Enquist (1934–2020).[58]

Children's literature

[edit]In the 1930s a new awareness of children's needs emerged. This manifested itself shortly after World War II, when Astrid Lindgren published Pippi Longstocking in 1945. Pippi's rebellious behaviour at first sparked resistance among some defenders of cultural values, but eventually she was accepted, and with that children's literature was freed from the obligation to promote moralism.[59][60]

Astrid Lindgren continued to publish many best-selling children's books which eventually made her the most read Swedish author, regardless of genre, with over 100 million copies printed throughout the world and translations into over 80 languages. In many other books Lindgren showed her fine understanding of children's thought and values; in The Brothers Lionheart about death, as well as a tale of bravery; in Mio, My Son, a fairy tale about friendship. But not all her stories had deep messages. Three books on Karlsson-on-the-Roof (1955, '62, '68) are about a short, chubby and mischievous man with a propeller on his back, who is befriended by a boy. Lindgren wrote twelve books about Emil of Maple Hills, a boy living in the Småland countryside in the early 1900s, who continuously gets intro trouble because of his pranks, yet in later life becomes a responsible and resourceful man, and the Chairman of the Municipality Council.[59]

One of the few fantasy writers in Swedish literature apart from Lindgren was the Finnish writer Tove Jansson (1914–2001), who wrote, in the Swedish language, about the Moomins. The Moomins are trolls who live in an economically and politically independent state, without any materialistic concerns. The Moomins have appealed to people in many different countries and Jansson's books have been translated into over 30 languages.[59][61]

Crime fiction

[edit]Before World War II, the Swedish detective novel was based on British and American models. After World War II, it developed in an independent direction. In the 1960s, Maj Sjöwall (1935–2020) and Per Wahlöö (1926–1975) collaborated to produce a series of internationally acclaimed detective novels about the detective Martin Beck. Other writers followed.

The most successful writer of Swedish detective novels is Henning Mankell (1948–2015), with his series on Kurt Wallander. They have been translated to 37 languages and have become bestsellers, particularly in Sweden and Germany.[62] Mankell's detective stories have been widely praised for their sociological themes, examining the effects on a liberal culture of immigration, racism, neo-Nazism etc. Many of the stories have been filmed no less than three times, twice by Swedish companies and most recently in an English-language series starring Kenneth Branagh. But Mankell has also written several other acclaimed books, such as Comédia Infantil (1995), about an abandoned street boy in the city of Maputo.[63]

Several other Swedish detective writers have become popular abroad, particularly in Germany; for example Liza Marklund (1962–), Håkan Nesser (1950–), Åsa Larsson, Arne Dahl, Leif G. W. Persson, Johan Theorin, Camilla Läckberg, Mari Jungstedt and Åke Edwardson. From 2004 and onwards, the deceased Stieg Larsson caused an international sensation with the Millennium Trilogy, continuing as a series with new novels being written by David Lagercrantz.

In the spy fiction genre, the most successful writer is Jan Guillou (1944–) and his best-selling books about the spy Carl Hamilton, many of which have also been filmed. Of Guillou's other works, the two most notable are his series on the Knight Templar Arn Magnusson and the semi-autobiographical novel with the metaphorical title Ondskan (The Evil).

Ballads

[edit]The Swedish ballad tradition had been initiated by Bellman in the late 18th century. In the 19th century, poetic songwriting fell into decline with the rise of university student choirs, until it was again revived in the 1890s. Poets increasingly continued the tradition of having their poetry set to music to give it a wider audience. In the early 1900s, a lot of poetry of the 90s poets Gustaf Fröding and Erik Axel Karlfeldt had been put to music.

Arguably the most renowned Swedish troubadour of the 20th century was however Evert Taube (1890–1976). He established himself as a performing artist in 1920 and toured Sweden for about three decades. He is best known for songs about sailors, ballads about Argentina, and songs about the Swedish countryside.[64]

Between 1962 up until his death, the most highly regarded singer-songwriter in the Swedish ballad tradition was Dutch immigrant Cornelis Vreeswijk (1937–1987). Some of his songs were leftist protest songs where he took it upon himself to speak for society's underdogs but he himself hated to be called a protest singer. His musical universe was much broader and he was for instance heavily influenced by the rich Swedish literature. After his death, Vreeswijk also gained appreciation for his poetic qualities.[64]

Literature in pop music lyrics

[edit]This literary period began in Sweden in the 1960s, influenced by artists from England and the U.S. At first, the literary quality in Swedish pop music was little more than an imitation of foreign models, and it took until the 1970s for an independent movement to emerge. In that decade, youth grassroots music reached unprecedented popularity, and opened the possibility for unestablished artists to have their music published. Because of the common political message these bands often presented, they are classified as Progg (short for "progressive"). While few Progg-artists actually produced anything worthwhile, there were some acts who stood out. Nationalteatern were significant because they were not only a musical group, but also theatre performers; and in the talented leftist artist Mikael Wiehe (1946–) of Hoola Bandoola Band, there was a renewal of Swedish ballad writing, in the direction of high quality proletarian lyrics.

One of the rebels of the 1970s was Ulf Lundell (1949–) who abandoned the grass root movement for rock 'n roll. In 1976, he broke through in literature with his debut novel Jack, a beatnik novel that came to represent a whole generation. While critics were not impressed, the novel sold in great numbers and is still appreciated by many.[63]

Finland

[edit]The Swedish language is an official language in Finland, with approximately 5.6% of the population having it as their mother tongue. Hence Swedish language literature has a considerable following in Finland, with several well-known Swedish-speaking Finnish writers, such as Bo Carpelan, Christer Kihlman and Tove Jansson. Jansson, perhaps best known for her Moomin books for children, wrote novels and short stories for adults, including Sommarboken, (1972, The Summer Book).

Finland-Swedish literature emerged in the late 19th century. Karl August Tavaststjerna (1860–1898) is considered to be first Finland-Swedish author. In the early 20th century, Edith Södergran, Elmer Diktonius and Gunnar Björling appeared as prominent modernist poets that had a strong influence on Modernist Swedish literature. Contemporary novelists include Ulla-Lena Lundberg, Kjell Westö and Monika Fagerholm.[65]

A cultural body representing such literature is the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland, which describes itself as "a versatile and future-oriented cultural institution of Finland-Swedish literature, culture and research." The Society is also a leading investor in the global equity and debt markets and a staunch defender of Finnish national interests, most recently against incursions by Swedish investors. This stance has caused some disquiet among Society members committed to the project of pan-Nordic literary appreciation.

21st century

[edit]Authors who have emerged in the 21st century include Sara Stridsberg, Jonas Hassen Khemiri, Lena Andersson, John Ajvide Lindqvist and Linda Boström Knausgård. Mikael Niemi and Fredrik Backman had international success with the bestselling novels Popular Music from Vittula and A Man Called Ove respectively. Several writers of crime fiction have had international success as part of the Nordic noir literary wave.[66]

Nobel laureates

[edit]Swedish writers awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the year it was awarded to them:

- Selma Lagerlöf, 1909 — "In appreciation of the lofty idealism, vivid imagination and spiritual perception that characterize her writings"[35]

- Verner von Heidenstam, 1916 — "In recognition of his significance as the leading representative of a new era in our literature"[67]

- Erik Axel Karlfeldt, 1931 — "For the poetry of Erik Axel Karlfeldt".[68] The acceptance speech elaborates: " The Swede would say that we celebrate this poet because he represents our character with a style and a genuineness that we should like to be ours, and because he has sung with singular power and exquisite charm of the tradition of our people, of all the precious features which are the basis for our feeling for home and country in the shadow of the pine-covered mountains.".[69]

- Pär Lagerkvist, 1951 — "For the artistic vigour and true independence of mind with which he endeavours in his poetry to find answers to the eternal questions confronting mankind"[70]

- Eyvind Johnson, 1974 (joint) — "For a narrative art, far-seeing in lands and ages, in the service of freedom"[71]

- Harry Martinson, 1974 (joint) — "For writings that catch the dewdrop and reflect the cosmos"[71]

- Tomas Tranströmer, 2011 — "Because, through his condensed, translucent images, he gives us fresh access to reality"[72]

Lists of important Swedish 20th century books

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]All page number references to "Gustafson" are made to the Swedish language edition of his book.

- ^ For example, both Birgitta of Sweden (14th century) and Emanuel Swedenborg (18th century) wrote most of their work in Latin, but since they came from Sweden, their works are generally considered part of Swedish literature by authorities such as Algulin (1989), and Delblanc, Lönnroth & Gustafsson (1999).

- ^ Gustafson, 1961 (Chapter 1)

- ^ Forntid och medeltid, Lönnroth, in Lönnroth, Göransson, Delblanc, Den svenska litteraturen, vol 1.

- ^ a b Lönnroth, L. & Delblanc, S. (1993). Den svenska litteraturen. 1, Från forntid till frihetstid : 800–1718. Stockholm : Bonnier Alba. ISBN 91-34-51408-2 p. 49.

- ^ Tigerstedt, p.68-70

- ^ Algulin, p.25, also agrees

- ^ Gustafson, p.54, also agrees

- ^ This account is given by Hägg (1996), p.83-84

- ^ This account is given in Tigerstedt (1971), p.68-70

- ^ a b c d Tigerstedt

- ^ Tigersted

- ^ Gustafson, pp.102–103

- ^ Warburg, p.57 (Online link)

- ^ Algulin, pp.38–39

- ^ Algulin, pp.39–41

- ^ Gustafson, p.108

- ^ Olsson (2009), p. 94

- ^ Olsson (2009), p. 137-139

- ^ a b Algulin, pp.67–68

- ^ Gustafson, pp.143–148

- ^ Gustafson, p.146

- ^ Algulin, p.82-83

- ^ Gustafson, pp.187–188

- ^ Algulin, p.86

- ^ Translated by Anne Storm as Die Woche mit Sara (2004), ISBN 3-463-40457-5 ZDF page Archived 10 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gustafson, pp.196–200

- ^ With time, however, the classification of 90s poets separate from the 1880 realism has become less prominent among scholars. A distinction between the two periods is made by Gustafson, pp.228–268 (1961) but not in Algulin, pp.109–115 (1989)

- ^ Algulin, p.109

- ^ a b Algulin pp.115–132

- ^ a b Gustafson, pp.238–257

- ^ August Strindberg and visual culture : the emergence of optical modernity in image, text, and theatre. Schroeder, Jonathan E., Stenport, and Anna Westerståhl,, Szalczer, Eszter, editors. London: Bloomsbury. 2019. ISBN 978-1-5013-6326-9. OCLC 1140132855.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Algulin, pp.137–140

- ^ Gustafson, vol2, p.11

- ^ Olsson (2009), p 300

- ^ a b The Nobel Prize in Literature 1909, The Official Web Site of the Nobel Foundation, 15 October 2006

- ^ Algulin, pp.158–160

- ^ Gustafson, vol. 2, p. 12

- ^ Gustafson, vol. 2, pp.7–16

- ^ As told by Gustafson, vol 2 (1961)

- ^ As reported by Algulin, p.169 (1989)

- ^ From her introduction to the translation by Paul Britten Austin, Harvill Press Edition, 2002, ISBN 1-84343-009-6.

- ^ Hjalmar Söderberg Den allvarsamma leken. Samlade skrifter 10 red. Bure Holmbäck & Björn Sahlin, Lind & Co 2012, p. 347-349, 359-361 (in Swedish)

- ^ Hjalmar Söderberg Söderbergsällskapet

- ^ Swedish literature Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Modern literature Sweden.se

- ^ Algulin, pp.191–194

- ^ Den svenska litteraturen 3 Från modernism till massmedial marknad : 1920–1995 / redaktion: Lars Lönnroth, Sven Delblanc, Sverker Göransson.

- ^ Klas Östergren Natur & Kultur

- ^ Tigerstedt (1975), pp. 474–476

- ^ Hägg (1996), pp.481–484

- ^ a b Lundkvist, Martinsson, Ekelöf, by Espmark & Olsson, in Delblanc, Lönnroth, Göransson, vol 3

- ^ Hägg (1996), pp. 528–524

- ^ Algulin, p.230-231

- ^ Poeten dold i Bilden, Lilja & Schiöler, in Lönnroth, Delblanc & Göransson (ed.), vol 3, pp.342–370

- ^ A title taken from Winnie the Pooh, which in English reads "Hipy papy bthuthdththuthda bthuthdy". Öyvind Fahlström, "HÄTILA RAGULPR PÅ FÅTSKLIABEN", Odyssé no. 2/3 1954.

- ^ Per Bäckström, Aska, Tomhet & Eld. Outsiderproblematiken hos Bruno K. Öijer, (diss.) Lund: Ellerströms förlag, 2003.

- ^ Dan Andersson britannica.com, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ Från hovteater till arbetarspel, Forser & TJäder, in Delblanc, Göransson & Lönnroth, Den svenska litteraturen, vol 3.

- ^ a b c Svensson, S., Så skulle världen bli som ny, in Lönnroth, Delblanc & Göransson (ed.), Den svenska litteraturen, vol. 3. (1999)

- ^ More information about Pippi Longstocking in Swedish culture can be found in the article Pippi Longstocking: Swedish rebel and feminist role model Archived 5 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine from the Swedish Institute. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ^ Tampere Art Museum website. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- ^ On the trail of Sweden's most famous detective Archived 15 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Swedish Institute. Retrieved 17 October 2006.

- ^ a b Chapter "Det populära kretsloppet", Hedman, Lönnroth & Ingvarsson, in Lönnroth, Delblanc & Göransson (ed.), vol 3.

- ^ a b Nöjets estradörer, Lönnroth, Lars, in Lönnroth, Delblanc & Göransson (ed.), vol 3, pp.275–297

- ^ "Finnish literature - Modernism, Poetry, Prose". britannica.com.

- ^ The Best Contemporary Scandinavian Fiction to Read Now Scandinavia Standard

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Literature 1916, The Official Web Site of the Nobel Foundation, 15 October 2006

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Literature 1931, The Official Web Site of the Nobel Foundation, 15 October 2006

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Literature 1931, Presentation Speech, The Official Web Site of the Nobel Foundation, 15 October 2006

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Literature 1951, The Official Web Site of the Nobel Foundation, 15 October 2006

- ^ a b The Nobel Prize in Literature 1974, The Official Web Site of the Nobel Foundation, 15 October 2006

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 2011 – Press Release". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ Results of the poll provided by Projekt Runeberg

- ^ Full list provided by Projekt Runeberg

- Algulin, Ingemar, A History of Swedish Literature, published by the Swedish Institute, 1989. ISBN 91-520-0239-X

- Gustafson, Alrik, Svenska litteraturens historia, 2 volums (Stockholm, 1963). First published as A History of Swedish Literature (American-Scandinavian Foundation, 1961).

- Hägg, Göran, Den svenska litteraturhistorian (Centraltryckeriet AB, Borås, 1996)

- Lönnroth, L., Delblanc S., Göransson, S. Den svenska litteraturen (ed.), 3 volumes (1999)

- Olsson, B., Algulin, I., et al, Litteraturens historia i Sverige (2009), ISBN 978-91-1-302268-0

- Warburg, Karl, Svensk Litteraturhistoria i Sammandrag (1904), p. 57 (https://runeberg.org/svlihist/ Online link], provided by Project Runeberg). This book is rather old, but it was written for schools and is probably factually correct. However, its focal point differs from current-day books.

- Nationalencyklopedin, article svenska

- Swedish Institute website, accessed 17 October 2006

- Tigerstedt, E.N., Svensk litteraturhistoria (Tryckindustri AB, Solna, 1971)

External links

[edit]- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 214–221.

Swedish Literature

- Project Runeberg a project that publishes freely available electronic versions of Nordic books.

- swedishpoetry.net a blog with English translations of well-known Swedish poems.