Louis Kahn

Louis Kahn | |

|---|---|

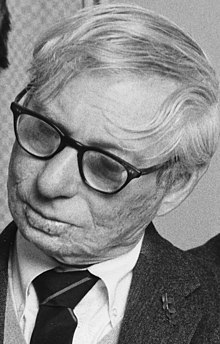

Kahn in June 1969 | |

| Born | Itze-Leib Schmuilowsky February 20, 1901 |

| Died | March 17, 1974 (aged 73) New York City, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | AIA Gold Medal RIBA Gold Medal |

| Buildings | Jatiya Sangsad Bhaban Yale University Art Gallery Salk Institute Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad Phillips Exeter Academy Library Kimbell Art Museum |

| Projects | Center of Philadelphia, Urban and Traffic Study |

Louis Isadore Kahn (born Itze-Leib Schmuilowsky; March 5 [O.S. February 20] 1901 – March 17, 1974) was an Estonian-born American architect[2] based in Philadelphia. After working in various capacities for several firms in Philadelphia, he founded his own atelier in 1935. While continuing his private practice, he served as a design critic and professor of architecture at Yale School of Architecture from 1947 to 1957. From 1957 until his death, he was a professor of architecture at the School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania.

Kahn created a style that was monumental and monolithic; his heavy buildings for the most part do not hide their weight, their materials, or the way they are assembled. He was awarded the AIA Gold Medal and the RIBA Gold Medal. At the time of his death, he was considered by some as "America's foremost living architect."[3]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]

Louis Kahn, whose original name was Itze-Leib (Leiser-Itze) Schmuilowsky (Schmalowski), was born into a poor Jewish family in the Russian Empire (present-day Estonia). His exact birthplace is disputed, but it is widely regarded to be Kuressaare, Saaremaa,[4] although some sources mention Pärnu.[5]

He spent his early childhood in Kuressaare on the island of Saaremaa, then part of the Russian Empire's Livonian Governorate. At the age of three, he saw coals in the stove and was captivated by the light of the coal. He put the coal in his apron, which caught on fire and burned his face.[6] He carried these scars for the rest of his life.[7]

In 1906, his family emigrated to the United States, as they feared that his father would be recalled into the military during the Russo-Japanese War. His birth year may have been inaccurately recorded in the process of immigration. According to his son's 2003 documentary film, the family could not afford pencils. They made their own charcoal sticks from burnt twigs so that Louis could earn a little money from drawings.[8] Later he earned money by playing piano to accompany silent movies in theaters. He became a naturalized citizen of the U.S. on May 15, 1914. His father changed their name to Kahn in 1915.[8]

Education

[edit]Kahn excelled in art from a young age, repeatedly winning the annual award for the best watercolor by a Philadelphia high school student. He was an unenthusiastic and undistinguished student at Philadelphia Central High School until he took a course in architecture in his senior year, which convinced him to become an architect. He turned down an offer to go to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts to study art under a full scholarship, instead working at a variety of jobs to pay his own tuition for a degree in architecture at the University of Pennsylvania School of Fine Arts. There, he studied under Paul Philippe Cret in a version of the Beaux-Arts tradition, one that discouraged excessive ornamentation.[9]

Career

[edit]After completing his Bachelor of Architecture in 1924, Kahn worked as senior draftsman in the office of the city architect, John Molitor. He worked on the designs for the 1926 Sesquicentennial Exposition.[10]

In 1928, Kahn made a European tour. He was interested particularly in the medieval walled city of Carcassonne, France, and the castles of Scotland, rather than any of the strongholds of classicism or modernism.[11] After returning to the United States in 1929, Kahn worked in the offices of Paul Philippe Cret, his former studio critic at the University of Pennsylvania, and then with Zantzinger, Borie and Medary in Philadelphia.[10]

In 1932, Kahn and Dominique Berninger founded the Architectural Research Group, whose members were interested in the populist social agenda and new aesthetics of the European avant-gardes. Among the projects Kahn worked on during this collaboration are schemes for public housing that he had presented to the Public Works Administration, which supported some similar projects during the Great Depression.[10] They remained unbuilt.

Among the more important of Kahn's early collaborations was one with George Howe.[12] Kahn worked with Howe in the late 1930s on projects for the Philadelphia Housing Authority and again in 1940, along with German-born architect Oscar Stonorov, for the design of housing developments in other parts of Pennsylvania.[13] A formal architectural office partnership between Kahn and Oscar Stonorov began in February 1942 and ended in March 1947, which produced fifty-four documented projects and buildings.[14][15]

Kahn did not arrive at his distinctive architectural style until he was in his fifties. Initially working in a fairly orthodox version of the International Style, he was strongly influenced by a stay as architect-in-residence at the American Academy in Rome during 1950, which marked a turning point in his career. After visiting the ruins of ancient buildings in Italy, Greece, and Egypt, he adopted a back-to-the-basics approach. He developed his own style, as influenced by earlier modern movements, but not limited by their sometimes-dogmatic ideologies. In the 1950s and 1960s, as a consultant architect for the Philadelphia City Planning Commission, Kahn developed several plans for the center of Philadelphia that were never executed.[16]

In 1961, he received a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts to study traffic movement in Philadelphia and to create a proposal for a viaduct system.[17][18]

He described this proposal at a lecture given in 1962 at the International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado:

In the center of town the streets should become buildings. This should be interplayed with a sense of movement which does not tax local streets for non-local traffic. There should be a system of viaducts which encase an area which can reclaim the local streets for their own use, and it should be made so this viaduct has a ground floor of shops and usable area. A model which I did for the Graham Foundation recently, and which I presented to Mr. Entenza, showed the scheme.[19]

Kahn's teaching career began at Yale University in 1947. He eventually was named as the Albert F. Bemis Professor of Architecture and Planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1956. Kahn then returned to Philadelphia to teach at the University of Pennsylvania from 1957 until his death, becoming the Paul Philippe Cret Professor of Architecture. He also was a visiting lecturer at Princeton University School of Architecture from 1961 to 1967.

In 1974, Kahn died of a heart attack[3] soon after a work trip to India.[3]

Awards and honors

[edit]Kahn was elected a Fellow in the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1953. He was made a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1964, the year he was awarded the Frank P. Brown Medal. In 1965, he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate Academician, and received an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts from Yale University.[20] He was made a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1968 and awarded the AIA Gold Medal, the highest award given by the AIA, in 1971, and the Royal Gold Medal by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), in 1972.[21][22] In 1971, he received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[23]

Personal life

[edit]Kahn had three children with three women. With his wife Esther he had a daughter, Sue Ann.[3] With Anne Tyng, who began her working collaboration and personal relationship with Kahn in 1945, he also had a daughter, Alexandra. When Tyng became pregnant in 1953, to mitigate the scandal, she went to Rome for the birth of their daughter.[24] With Harriet Pattison, he had a son, Nathaniel Kahn. Anne Tyng was an architect and teacher, while Harriet Pattison was a pioneering landscape architect.[25] Kahn's obituary in The New York Times, written by Paul Goldberger, mentions only Esther and his daughter by her as survivors.[3]

Documentary

[edit]In 2003, Nathaniel Kahn released a documentary about his father, My Architect: A Son's Journey. The Oscar-nominated film provides views and insights into Kahn's architecture while exploring him personally through his family, friends and colleagues.[26]

Designs

[edit]

- Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut (1951–1953), the first significant commission of Louis Kahn. The ceilings, which are three feet (0.9 meters) thick, consist of a grid of triangular openings that draw the eye upward into dimly-lit, three-sided pyramidal spaces. These exposed spaces provide the means for channeling the heating, cooling, and electrical services throughout the galleries.[27]

- Richards Medical Research Laboratories, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1957–1965), a breakthrough in Kahn's career that helped set new directions for modern architecture with its clear expression of served and servant spaces and its evocation of the architecture of the past.

- The Salk Institute, La Jolla, California (1959–1965) was to be a campus composed of three main clusters: meeting and conference areas, living quarters, and laboratories. Only the laboratory cluster, consisting of two parallel blocks enclosing a water garden, was built. The two laboratory blocks frame a long view of the Pacific Ocean, accentuated by a thin linear fountain that seems to reach for the horizon. It has been named "arguably the defining work" of Kahn.[28]

- First Unitarian Church, Rochester, New York (1959–1969), named as one of the greatest religious structures of the twentieth century by Paul Goldberger, the Pulitzer Prize-winning architectural critic.[29] Tall, narrow window recesses create an irregular rhythm of shadows on the exterior while four light towers flood the sanctuary walls with indirect, natural light.

- Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College and Hospital, Dhaka, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh)

- Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, in Ahmedabad, India (1961)

- Eleanor Donnelly Erdman Hall, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania (1960–1965), designed as a modern Scottish castle.[30]

- Phillips Exeter Academy Library, Exeter, New Hampshire (1965–1972), awarded the Twenty-five Year Award by the American Institute of Architects in 1997. Its dramatic atrium features enormous circular openings into the book stacks.

- Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas (1967–1972), features repeated bays of cycloid-shaped barrel vaults with light slits along the apex, which bathe the artwork on display in an ever-changing diffuse light.

- Arts United Center, Fort Wayne, Indiana (1973), The only building realized of a ten-building Arts Campus vision, Kahn's only theatre and building in the Midwest

- Hurva Synagogue, Jerusalem, Israel, (1968–1974), unbuilt

- Yale Center for British Art, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut (1969–1974)

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, Roosevelt Island, New York (1972–1974), construction completed 2012

- Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban (National Assembly Building) in Dhaka, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) was Kahn's last project, developed 1962 to 1974. Kahn got the design contract with the help of Muzharul Islam, one of his students at Yale University, who worked with him on the project. The Bangladeshi Parliament building is the centerpiece of the national capital complex designed by Kahn, which includes hostels, dining halls, and a hospital. According to Robert McCarter, author of Louis I. Kahn, "it is one of the twentieth century's greatest architectural monuments, and is without question Kahn's magnum opus."[31]

Timeline of works

[edit]

All dates refer to the year project commenced

- 1935 – Jersey Homesteads Cooperative Development, Hightstown, New Jersey

- 1940 – Jesse Oser House, 628 Stetson Road, Elkins Park, Pennsylvania

- 1944 – Carver Court, Foundry Street, Coatsville, Pennsylvania

- 1947 – Phillip Q. Roche House, 2101 Harts Lane, Conshohocken, Pennsylvania

- 1950 – Morton and Lenore Weiss House, 2935 Whitehall Rd, East Norriton Township, Pennsylvania[32]

- 1951 – Yale University Art Gallery, 1111 Chapel Street, New Haven, Connecticut

- 1952 – City Tower Project, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (unbuilt)

- 1954 – Jewish Community Center (including Trenton Bath House), 999 Lower Ferry Road, Ewing, New Jersey

- 1956 – Wharton Esherick Studio, 1520 Horseshoe Trail, Malvern, Pennsylvania (designed with Wharton Esherick)

- 1957 – Richards Medical Research Laboratories, University of Pennsylvania, 3700 Hamilton Walk, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- 1957 – Fred E. and Elaine Cox Clever House, 417 Sherry Way, Cherry Hill, New Jersey

- 1959 – Margaret Esherick House, 204 Sunrise Lane, Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania[33]

- 1958 – Tribune Review Publishing Company Building, 622 Cabin Hill Drive, Greensburg, Pennsylvania

- 1959 – Salk Institute for Biological Studies, 10 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California

- 1959 – First Unitarian Church, 220 South Winton Road, Rochester, New York

- 1960 – Erdman Hall Dormitories, Bryn Mawr College, Morris Avenue, Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania

- 1960 – Norman Fisher House, 197 East Mill Road, Hatboro, Pennsylvania

- 1961 – Point Counterpoint, a converted barge performance venue used by the American Wind Symphony Orchestra

- 1961 – Philadelphia's Mikveh Israel, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (unbuilt)

- 1961 – Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India

- 1962 – Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban, the National Assembly Building of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 1963 – President's Estate, Islamabad, Pakistan (unbuilt)

- 1965 – Phillips Exeter Academy Library, Front Street, Exeter, New Hampshire

- 1965 – Phillips Exeter Academy Dining Hall, Elm Street, Exeter, New Hampshire

- 1966 – Kimbell Art Museum, 3333 Camp Bowie Boulevard, Fort Worth, Texas

- 1966 – Olivetti-Underwood Factory, Valley Road, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- 1966 – Temple Beth El of Northern Westchester, Chappaqua, New York

- 1968 – Hurva Synagogue, Jerusalem, Israel (unbuilt)

- 1969 – Yale Center for British Art, Yale University, 1080 Chapel Street, New Haven, Connecticut

- 1971 – Steven Korman House, Sheaff Lane, Fort Washington, Pennsylvania

- 1973 – Arts United Center (Formerly known as the Fine Arts Foundation Civic Center), Fort Wayne, Indiana[34]

- 1974 – Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, Roosevelt Island, New York City, completed 2012.[35]

- 1976 – Point Counterpoint II, an improved concert venue for the American Wind Symphony Orchestra, is debuted posthumously

- 1979 – Flora Lamson Hewlett Library of the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California[36]

Legacy

[edit]

Louis Kahn's work infused the International style with a fastidious, highly personal taste. Isamu Noguchi called him "a philosopher among architects." He was concerned with creating strong formal distinctions between served spaces and servant spaces. What he meant by servant spaces was not spaces for servants, but rather spaces that serve other spaces, such as stairwells, corridors, restrooms, or any other back-of-house function such as storage space or mechanical rooms. His palette of materials tended toward heavily textured brick and bare concrete, the textures often reinforced by juxtaposition to highly refined surfaces such as travertine marble. Kahn argued that brick can be more than the basic building material:

If you think of Brick, you say to Brick, 'What do you want, Brick?' And Brick says to you, 'I like an Arch.' And if you say to Brick, 'Look, arches are expensive, and I can use a concrete lintel over you. What do you think of that, Brick?' Brick says, 'I like an Arch.' And it's important, you see, that you honor the material that you use. ... You can only do it if you honor the brick and glorify the brick instead of shortchanging it.[19]

In addition to the influence Kahn's better-known work has on contemporary architects (such as Muzharul Islam, Tadao Ando), some of his work (especially the unbuilt City Tower Project) became very influential among the high-tech architects of the late twentieth century (such as Renzo Piano, who worked in Kahn's office, Richard Rogers, and Norman Foster).[37] His prominent apprentices include Muzharul Islam, Moshe Safdie, Robert Venturi, Jack Diamond, and Charles Dagit.

Many years after his death, Kahn continues to provoke controversy. Before his Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park at the southern tip of Roosevelt Island was built,[38] the editors of The New York Times opined:

There's a magic to the project. That the task is daunting makes it worthy of the man it honors, who guided the nation through the Depression, the New Deal and a world war. As for Mr. Kahn, he died in 1974, as he passed alone through New York City's Penn Station. In his briefcase were renderings of the memorial, his last completed plan.[39]

The editorial describes Kahn's plan as:

... simple and elegant. Drawing inspiration from Roosevelt's defense of the Four Freedoms—of speech and religion, and from want and fear—he designed an open 'room and a garden' at the bottom of the island. Trees on either side form a 'V' defining a green space, and leading to a two-walled stone room at the water's edge that frames the United Nations and the rest of the skyline.

A group spearheaded by William J. vanden Heuvel raised over $50 million in public and private funds between 2005 and 2012 to establish the memorial. Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park officially opened to the public on October 24, 2012.

In popular culture

[edit]Kahn was the subject of the 2003 Oscar-nominated documentary film My Architect: A Son's Journey, presented by Nathaniel Kahn, his son.[26] Kahn's complicated family life inspired the "Undaunted Mettle" episode of Law & Order: Criminal Intent.

In the 1993 film Indecent Proposal, character David Murphy (played by Woody Harrelson), referenced Kahn during a lecture to architecture students, attributing the quote "Even a brick wants to be something" to Kahn.

Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Lewis Spratlan, with collaborators Jenny Kallick and John Downey (Amherst College, class of 2003), composed the chamber opera Architect as a character study of Kahn. The premiere recording was due to be released in 2012 by Navona Records.

Gallery

[edit]-

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut (1951–1953)

-

Coffered ceiling in Yale University Art Gallery (1951–1953)

-

Stairwell in Yale University Art Gallery (1951–1953)

-

Trenton Bath House and Day Camp (1954)

-

Wharton Esherick Studio, 1520 Horseshoe Trail, Malvern, Pennsylvania (1956). Designed with Wharton Esherick

-

Richards Medical Research Laboratories, University of Pennsylvania, 3700 Hamilton Walk, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1957–1965)

-

Interior of First Unitarian Church, Rochester, New York (1959)

-

Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India (1961)

-

Interior of Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas (1966)

-

Yale Center for British Art, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut (1969–1974)

-

Parliament of Bangladesh (2014)

-

National Assembly of Bangladesh assembly hall (2014)

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Paulus, Karin; Pesti, Olavi (November 23, 2006). "Kus sündis Louis Kahn?" [Where was Louis Kahn born?]. EAA Architecture News (in Estonian). Eesti Ekspress.

- ^ Van Voolen, Edward (September 30, 2006). My Grandparents, My Parents and I: Jewish art and culture. Prestel. p. 138. ISBN 978-3791333625. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

The Estonian-born architect Kahn (1901–1974), who immigrated with his family to Philadelphia in 1906

- ^ a b c d e Goldberger, Paul (March 20, 1974). "Louis I. Kahn Dies; Architect was 73". The New York Times. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ Kus sündis Louis Kahn?

- ^ Kahn biography

- ^ "Kus sündis Louis Kahn?" (in Estonian). Eesti Ekspress. Retrieved September 28, 2006.

- ^ Commstock, Paul. "An Interview with Louis Kahn Biographer Carter Wiseman," Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine California Literary Review. June 15, 2007.

- ^ a b My Architect: A Son's Journey Archived January 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, SBS Hot Docs, January 15, 2008

- ^ Lesser, Wendy (March 14, 2017). You Say to Brick: The Life of Louis Kahn. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 56–60. ISBN 978-0374713317.

- ^ a b c "Louis Isadore Kahn (1901–1974)", Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

- ^ Johnson, Eugene J. "A Drawing of the Cathedral of Albi by Louis I. Kahn," Gesta, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 159–165.

- ^ Howe, George (1886–1955), Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

- ^ Stonorov, Oskar Gregory (1905–1970), Philadelphia Architects and Buildings

- ^ "The Pacific Coast Architecture Database". The Pacific Coast Architecture Database. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ "List of Buildings and Projects by Stonorov & Kahn Associated Architects". Philadelphia Architects and Buildings. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 408. ISBN 9780415252256.

- ^ Philadelphia City Planning: Market Street East Project Page Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ MoMA.org | The Collection | Louis I. Kahn. Traffic Study, project, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Plan of proposed traffic-movement pattern. 1952

- ^ a b Kahn, Louis I. (2003). Robert C. Twombly (ed.). Louis Kahn: Essential Texts. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 158. ISBN 978-0393731132.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees Since 1702 | Office of the Secretary and Vice President for University Life". secretary.yale.edu. Retrieved June 5, 2024.

- ^ "Gold Medal Recipients: Louis Isadore Kahn, FAIA". American Institute of Architects. Archived from the original on July 16, 2007. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ "List of Royal Gold Medal winners 1848–2008" (PDF). RIBA. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 2, 2014.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ Saffron, Inga (January 7, 2012). "Anne Tyng, 91, groundbreaking architect". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ Sisson, Patrick (April 20, 2016). "Pioneering Landscape Architect Harriet Pattison Finally Gets Her Due". Curbed. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Stephen Holden (March 29, 2003). "Son of a Celebrated Father Traces His Elusive Past". The New York Times.

- ^ McCarter, Robert (2005). Louis I. Kahn. London: Phaidon Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0714849713.

- ^ Trachtenberg, Marvin (September 1, 2016). "RECORD's Top 125 Buildings: 51–75: Salk Institute". Architectural Record.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (December 26, 1982). "Housing for the Spirit". The New York Times.

- ^ "Erdman Hall". Bryn Mawr College. Archived from the original on October 23, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ McCarter, Robert (2005). Louis I. Kahn. London: Phaidon Press. p. 258,270. ISBN 978-0714849713.

- ^ "Kahn-designed Weiss House in East Norriton on the state's 'At-Risk' list". Montco Today. February 11, 2019.

- ^ Margaret Esherick House from Flickr.

- ^ "Arts United Center". Arts United. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ Foderaro, Lisa W. (October 17, 2012). "Dedicating Park to Roosevelt and His View of Freedom". The New York Times. Retrieved November 14, 2012. The work was commissioned in 1972, and Kahn was carrying his designs for the project when he died.

- ^ Glenn, Lucinda (November 2001). "Library History". Graduate Theological Union. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ "Piano Takes on Kahn at Kimbell Museum Expansion, Kimbell Museum" (Press release). Archdaily. November 22, 2013.

- ^ "The Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial, Four Freedoms Park" (Press release). Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute. September 26, 2016. Archived from the original on December 6, 2007.

- ^ "A Roosevelt for Roosevelt Island". The New York Times. November 5, 2007.

Cited sources

[edit]- Norberg-Schulz, Christian (1980). Louis Kahn. Idea e Immagine. Rome, ITA: Officina Edizioni. ISBN 84-85434-14-5.

- Curtis, William (1987). Modern Architecture Since 1900 (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall. pp. 309–316. ISBN 978-0714833569.

- Dagit, Charles E. Jr. (2013). Louis I. Kahn – Architect: Remembering the Man and Those Who Surrounded Him. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-5179-4.

- Ronner, Heinz; Sharad Jhaveri; Alessandro Vasella (1977). Louis I.Kahn: Complete Works 1935–1974 (first ed.). Boulder: Westview Press. p. 456. ISBN 978-0891586487.

- Leslie, Thomas (2005). Louis I.Kahn: Building Art, Building Science. New York: George Braziller. ISBN 978-0807615409.

- Lesser, Wendy (March 14, 2017). You Say to Brick: The Life of Louis Kahn. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0374279974.

- McCarter, Robert (July 16, 2005). Louis I. Kahn. Phaidon Press Ltd. p. 512. ISBN 978-0714849713.

- Wiseman, Carter (2007). Louis I. Kahn: Beyond Time and Style: A Life in Architecture (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-73165-1.

- Larson, Kent (2000). Louis I. Kahn: Unbuilt Masterworks. New York: Monacelli Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-1580930147.

- Rosa, Joseph (2006). Peter Gossel (ed.). Louis I. Kahn: Enlightened space. Cologne: Taschen GmbH. p. 96. ISBN 978-3836543842.

- Merrill, Michael (2010). Louis Kahn: Drawing to Find Out. Baden: Lars Mueller Publishers. p. 240. ISBN 978-3-03778-221-7.

- Merrill, Michael (2010). Louis Kahn: On the Thoughtful Making of Spaces. Baden: Lars Mueller Publishers. p. 240. ISBN 978-3-03778-220-0.

- Vassella, Alessandro (2013). Louis Kahn: Silence and Light. Zurich: Park Books. pp. 168, 1 Audio–CD. ISBN 978-3-906027-18-0.

- Solomon, Susan (August 31, 2009). Louis I. Kahn's Jewish Architectur, Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life. Brandeis. ISBN 978-1584657880.

Further reading

[edit]- Brownlee, Robert; De Long, David G. (October 15, 1991). Louis I. Kahn: in the realm of architecture. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0847813230.

- Goldhagen, Sarah Williams, Louis Kahn's Situated Modernism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), ISBN 0300077866.

- Kahn, Louis. Louis Kahn: Essential Texts, edited by Robert Twombly. London & New York: WW Norton & Company, 2003.

- Lesser, Wendy (2017). You Say to Brick: The Life of Louis Kahn. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374279974.

- Mowla, Qazi Azizul 2007 Kahn's Creation in Dhaka – Re Evaluated, Jahangirnagar Planning Review,(Journal: issn=1728-4198).Vol.5, June 2007, Dhaka, pp. 85–96.

- Kohane, Peter (2001). "Louis Kahn's Theory of 'Inspired Ritual' and Architectural Space". Architectural Theory Review. 6 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1080/13264820109478418. S2CID 144340999.

- Choudhury, Bayezid Ismail 2014. PhD dissertation at the University of Sydney 'The genesis of Jatio Sangsad Bhaban at Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka'

- Sully, Nicole (2019). "Architecture from the Ouija Board: Louis Kahn's Roosevelt Memorials and the Posthumous Monuments of Modernism". Fabrications: The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand. 29 (1): 60–85. doi:10.1080/10331867.2018.1540083. S2CID 191998111.

- Wurman, Richard Saul, ed. (1986). What will be has always been: the words of Louis I. Kahn. New York: Access Press: Rizzoli. ISBN 0847806065.

- Harriet Pattison: Our days are like full years : a memoir with letters from Louis Kahn, New Haven : Yale University Press, [2020], ISBN 978-0-300-22312-5

- Luigi Monzo (Review): Michael Merrill: Louis Kahn. The Importance of a Drawing (2021), in: Journal für Kunstgeschichte, 27.2023/3, pp. 244–256.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Louis Kahn at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Louis Kahn at Wikimedia Commons

- Modernist architects from the United States

- 1901 births

- 1974 deaths

- Louis Kahn buildings

- American ecclesiastical architects

- Architecture educators

- Estonian architects

- Jewish architects

- Modernist architects

- Fellows of the American Institute of Architects

- Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal

- Architects from Philadelphia

- Architecture of Phillips Exeter Academy

- American people of Estonian-Jewish descent

- Estonian emigrants to the United States

- Central High School (Philadelphia) alumni

- University of Pennsylvania School of Design alumni

- University of Pennsylvania faculty

- Yale School of Architecture faculty

- People from Kuressaare

- 20th-century American architects

- Recipients of the AIA Gold Medal

- Olivetti people

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 20th-century Estonian Jews

- 20th-century American Jews