Box jellyfish

| Box jellyfish Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Chironex sp. | |

| |

| Carukia barnesi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Subphylum: | Medusozoa |

| Class: | Cubozoa Werner, 1973[1] |

| Orders | |

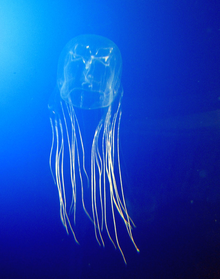

Box jellyfish (class Cubozoa) are cnidarian invertebrates distinguished by their box-like (i.e. cube-shaped) body.[2] Some species of box jellyfish produce potent venom delivered by contact with their tentacles. Stings from some species, including Chironex fleckeri, Carukia barnesi, Malo kingi, and a few others, are extremely painful and often fatal to humans.[3]

Taxonomy and systematics

[edit]Historically, cubozoans were classified as an order of Scyphozoa until 1973, when they were put in their own class due to their unique biological cycle (lack of strobilation) and morphology.[4]

At least 51 species of box jellyfish were known as of 2018.[5] These are grouped into two orders and eight families.[6] A few new species have since been described, and it is likely that additional undescribed species remain.[7][8][9]

Cubozoa represents the smallest cnidarian class with approximately 50 species.[10][better source needed]

Class Cubozoa

- Order Carybdeida

- Family Alatinidae

- Family Carukiidae

- Family Carybdeidae

- Family Tamoyidae

- Family Tripedaliidae

- Order Chirodropida

- Family Chirodropidae

- Family Chiropsalmidae

- Family Chiropsellidae

Description

[edit]

The medusa form of a box jellyfish has a squarish, box-like bell, from which its name is derived. From each of the four lower corners of this hangs a short pedalium or stalk which bears one or more long, slender, hollow tentacles. The rim of the bell is folded inwards to form a shelf known as a velarium which restricts the bell's aperture and creates a powerful jet when the bell pulsates.[11] As a result, box jellyfish can move more rapidly than other jellyfish; speeds of up to 6 metres (20 ft) per minute have been recorded.[12]

In the center of the underside of the bell is a mobile appendage called the manubrium which somewhat resembles an elephant's trunk. At its tip is the mouth. The interior of the bell is known as the gastrovascular cavity. It is divided by four equidistant septa into a central stomach and four gastric pockets. The eight gonads are located in pairs on either side of the four septa. The margins of the septa bear bundles of small gastric filaments which house nematocysts and digestive glands and help to subdue prey. Each septum is extended into a septal funnel that opens onto the oral surface and facilitates the flow of fluid into and out of the animal.[11]

The box jellyfish's nervous system is more developed than that of many other jellyfish. They possess a ring nerve at the base of the bell that coordinates their pulsing movements, a feature found elsewhere only in the crown jellyfish. Whereas some other jellyfish have simple pigment-cup ocelli, box jellyfish are unique in the possession of true eyes, complete with retinas, corneas and lenses.[13] Their eyes are set in clusters at the ends of sensory structures called rhopalia which are connected to their ring nerve. Each rhopalium contains two image-forming lens eyes. The upper lens eye looks straight up out of the water with a field of view that matches Snell's window. In species such as Tripedalia cystophora, the upper lens eye is used to navigate to their preferred habitats at the edges of mangrove lagoons by observing the direction of the tree canopy.[14] The lower lens eye is primarily used for object avoidance. Research has shown that the minimum visual angle for obstacles avoided by their lower lens eyes matches the half-widths of their receptive fields.[15] Each rhopalium also has two pit eyes on either side of the upper lens eye which likely act as mere light meters, and two slit eyes on either side of the lower lens eye which are likely used to detect vertical movement.[16] In total, the box jellyfish have six eyes on each of their four rhopalia, creating a total of 24 eyes. The rhopalia also feature a heavy crystal-like structure called a statolith, which, due to the flexibility of the rhopalia, keep the eyes oriented vertically regardless of the orientation of the bell.[14]

Box jellyfish also display complex, probably visually-guided behaviors such as obstacle avoidance and fast directional swimming.[17] Research indicates that, owing to the number of rhopalial nerve cells and their overall arrangement, visual processing and integration at least partly happen within the rhopalia of box jellyfish.[17] The complex nervous system supports a relatively advanced sensory system compared to other jellyfish, and box jellyfish have been described as having an active, fish-like behavior.[18]

Depending on species, a fully grown box jellyfish can measure up to 20 cm (8 in) along each box side (30 cm or 12 in in diameter), and the tentacles can grow up to 3 m (10 ft) in length. Its weight can reach 2 kg (4+1⁄2 lb).[19] However, the thumbnail-sized Irukandji is a box jellyfish, and lethal despite its small size. There are about 15 tentacles on each corner. Each tentacle has about 500,000 cnidocytes, containing nematocysts, a harpoon-shaped microscopic mechanism that injects venom into the victim.[20] Many different kinds of nematocysts are found in cubozoans.[21]

Distribution

[edit]

Although the notoriously dangerous species of box jellyfish are largely restricted to the tropical Indo-Pacific region, various species of box jellyfish can be found widely in tropical and subtropical oceans (between 42° N and 42 °S),[4] including the Atlantic Ocean and the east Pacific Ocean, with species as far north as California (Carybdea confusa), the Mediterranean Sea (Carybdea marsupialis)[22] and Japan (such as Chironex yamaguchii),[7] and as far south as South Africa (for example, Carybdea branchi)[8] and New Zealand (such as Copula sivickisi).[23] Though box jellies are known to inhabit the Indo-Pacific region, there is very little collected data or studies proving this. It was only in 2014, that the first ever box jelly sightings (Tripedalia cystophora) were officially published in Australia, Thailand and the Indian Ocean.[24] There are three known species in Hawaiian waters, all from the genus Carybdea: C. alata, C. rastoni, and C. sivickisi.[25] Within these tropical and subtropical environments, box jellyfish tend to reside closer to shore. They have been spotted in near-shore habitats such as mangroves, coral reefs, kelp forests, and sandy beaches.[26]

Recently, in 2023, a new genus and species of box jellyfish was discovered in the Indo-Pacific region, specifically the Gulf of Thailand. Discovered and named after scientist Lisa-ann Gershwin, this new species of box jellyfish, Gershwinia thailandensis, is a member of the Carukiidae family. Gershwinia thailandensis is described as its own new species as it has sensory structures with specialized horns and lacks a common digestive system among box jelly, the stomach gastric phaecellae.[27] Due to this and other observations, structural and biological, Gershwinia thailandensis was accepted as a new species of box jellyfish.[28]

Detection

[edit]

Cubozoans are widely distributed throughout tropical and subtropical regions, yet the detection of these organisms can be quite difficult and costly due to a high amount of variation in their occurrence and abundance, their translucent body, two different life stages (medusa and polyp), and vast amounts of size variability within the different species in the class Cubozoa.[29]

Understanding the ecological distribution of cubozoans can be difficult work, and some of the costly methods like visual observations, a variety of different nets, light attraction techniques, and most recently the use of drones have had some levels of success in locating and tracking different species of cubozoa, but are limited by both anthropogenic and environmental factors.[30]

A new form of detection, environmental DNA (eDNA), has been developed and employed to help aid in the analysis of the populations of box jellyfish which can be implemented to mitigate the effects that box jellyfish have on coastal anthropogenic activities.[29][31] This relatively easy and cost-effective method utilizes extra-organismal genetic material that can be found in the water column via shedding throughout the lifespan of an organism.[30][31]

This process for identifying box jellyfish using the eDNA technique involves collecting a water sample and filtering the sample through a cellulose nitrate membrane filter to extract any genetic material from the water sample.[30] Once the DNA is extracted, it is analyzed for species-specific matches to see if the eDNA sequences sampled correlate with existing DNA sequences for box jellyfish.[30] Given the results, the presence or absence of the box jellyfish can be indicated through the matching of genetic material.[29] If a match is found, then the box jellyfish was present in the area, additionally, the quantity of genetic material can indicate the biomass or abundance of the box jellyfish in the given sampling site.[31] The utilization of eDNA can provide a cost-effective and efficient way to monitor populations of box jellyfish in both medusa and polyp life stages, to then use the data to help understand more about their ecology and limit the effects on coastal anthropogenic activities.[29]

Ecology

[edit]Age and growth

[edit]It has been found that the statoliths, which are composed of calcium sulfate hemihydrate, exhibit clear sequential incremental layers, thought to be laid down on a daily basis. This has enabled researchers to estimate growth rates, ages, and age to maturity. Chironex fleckeri, for example, increases its inter-pedalia distance (IPD) by 3 mm (1⁄8 in) per day, reaching an IPD of 50 mm (2 in) when 45 to 50 days old. The maximum age of any individual examined was 88 days by which time it had grown to an IPD of 155 mm (6 in).[32] In the wild, the box jellyfish will live up to 3 months, but can survive up to seven or eight months in a science lab tank.[33]

Behavior

[edit]The box jellyfish actively hunts its prey (small fish), rather than drifting as do true jellyfish. They are strong swimmers, capable of achieving speeds of up to 1.5 to 2 metres per second or about 4 knots (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph).[19] and rapidly turning up to 180° in a few bell contractions.[4] Some species are capable of avoiding obstacles.[4]

The majority of box jellyfishes feed by extending their tentacles and accelerating for a short time upwards, then turn upside-down and stop pulsating. Then the jellyfish slowly sinks, until prey finds itself entangled by tentacles. At this point the pedalia fold and bring the prey to the oral opening.[4]

The venom of cubozoans is distinct from that of scyphozoans, and is used to catch prey (small fish and invertebrates, including prawns and bait fish) and for defence from predators, which include the butterfish, batfish, rabbitfish, crabs (blue swimmer crab) and various species of turtle including the hawksbill sea turtle and flatback sea turtle. It seems that sea turtles are unaffected by the stings because they seem to relish box jellyfish.[19]

Reproduction

[edit]

Cubozoans usually have an annual life cycle. Box jellyfish reach sexual maturity when their bell diameter reaches 5 millimeters.[34] Chirodropida reproduces by external fertilization. Carybdeida instead reproduces by internal fertilization and is ovoviviparous; sperm is transferred by spermatozeugmata, a type of spermatophore.[35] Hours after the fertilization, the female releases an embryo strand that contains its own nematocytes; both euryteles and isorhizas.[36] Cubozoas are the only class of cnidarian that contains species that perform the “wedding dance” to transfer the spermatophores from the male into the females, including the Carybdea sivickisi species.[34]

It is previously believed that medusa species only reproduce once in their life before dying a few weeks later, a semelparity lifestyle.[34] Alternatively, in July 2023, the box jelly species Chiropsalmus quadrumanus, were found to potentially have iteroparous reproduction, meaning they reproduce multiple times in their life. Oogenesis appears to happen numerous times as oocytes are discovered in four stages; pre-vitellogenic, early vitellogenic, mid vitellogenic, and late vitellogenic.[37] Continuous research needs to be conducted to determine if box jellyfish are semelparity or iteroparous, or if it is species dependent.

Genetics

[edit]Box jellyfish have a mitochondrial genome that is arranged into eight linear chromosomes.[38] As of 2022, only two Cubozoan species were fully sequenced, Alatina alata and Morbakka virulenta. A. alata has 66,156 genes, the largest gene count for any Medusozoan.[39] The mitochondrial genome of box jellyfish is uniquely structured into multiple linear fragments.[4] Each one of the eight linear chromosomes have between one and four genes including two extra genes. These two extra genes (mt-polB and orf314) encode proteins.[38] There are only a few studies that have been completed involving the research of mitochondrial gene expression in box jellyfish.[38]

Danger to humans

[edit]

Box jellyfish have been long known for their powerful sting. The lethality of the Cubozoan venom to humans is the primary reason for its research.[38] Although unspecified species of box jellyfish have been called in newspapers "the world's most venomous creature"[40] and the deadliest creature in the sea,[41] only a few species in the class have been confirmed to be involved in human deaths; some species are not harmful to humans, possibly delivering a sting that is no more than painful.[9] When the venom of the box jellyfish was sequenced, it was found that more than 170 toxin proteins were identified.[38] The high quantity of toxin proteins that the box jellyfish possess is the reason they are known to be so dangerous. Stings from the box jellyfish can lead to skin irritation, cardiotoxicity, and can even be fatal.[38]

Australia

[edit]Hugo Flecker, who worked on various venomous animal species and poisonous plants, was concerned at the unexplained deaths of swimmers. He identified the cause as the species of box jellyfish later named Chironex fleckeri. In 1945, he described another jellyfish envenoming which he named the "Irukandji Syndrome", later identified as caused by the box jellyfish species Carukia barnesi.[42]

In Australia, fatalities are most often caused by the largest species of this class of jellyfish, Chironex fleckeri, one of the world's most venomous creatures.[42] After severe Chironex fleckeri stings, cardiac arrest can occur quickly, within just two minutes.[43] C. fleckeri has caused at least 79 deaths since the first report in 1883,[44][45] but even in this species most encounters appear to result only in mild envenoming.[46] While most recent deaths in Australia have been in children, including a 14-year old who died in February 2022,[47] which is linked to their smaller body mass,[44] in February 2021, a 17-year-old boy died about 10 days after being stung while swimming at a beach on Queensland's western Cape York.[48] The previous fatality was in 2007.[49]

At least two deaths in Australia have been attributed to the thumbnail-sized Irukandji box jellyfish.[50][51] People stung by these may suffer severe physical and psychological symptoms, known as Irukandji syndrome.[52] Nevertheless, most victims do survive, and out of 62 people treated for Irukandji envenomation in Australia in 1996, almost half could be discharged home with few or no symptoms after 6 hours, and only two remained hospitalized approximately a day after they were stung.[52]

Preventative measures in Australia include nets deployed on beaches to keep jellyfish out, and jugs of vinegar placed along swimming beaches to be used for rapid first aid.[46]

Hawaii: research and dangers

[edit]Researchers at the University of Hawaii's Department of Tropical Medicine found the venom causes cells to become porous enough to allow potassium leakage, causing hyperkalemia, which can lead to cardiovascular collapse and death as quickly as within 2 to 5 minutes.

In Hawaii, box jellyfish numbers peak approximately seven to ten days after a full moon, when they come near the shore to spawn. Sometimes, the influx is so severe that lifeguards have closed infested beaches, such as Hanauma Bay, until the numbers subside.[53][54]

Malaysia, Philippines, Japan, Thailand, and Texas

[edit]In parts of the Malay Archipelago, the number of lethal cases is far higher than in Australia. In the Philippines, an estimated 20–40 people die annually from Chirodropid stings, probably owing to limited access to medical facilities and antivenom.[55]

The recently discovered and very similar Chironex yamaguchii may be equally dangerous, as it has been implicated in several deaths in Japan.[7] It is unclear which of these species is the one usually involved in fatalities in the Malay Archipelago.[7][56]

Warning signs and first aid stations have been erected in Thailand following the death of a 5-year-old French boy in August 2014.[57][58] A woman died in July 2015 after being stung off Ko Pha Ngan,[59] and another at Lamai Beach at Ko Samui on 6 October 2015.[60]

In 1990, a 4-year-old child died after being stung by Chiropsalmus quadrumanus at Galveston Island, Texas, on the Gulf of Mexico. Either this species or Chiropsoides buitendijki is considered the likely perpetrator of two deaths in West Malaysia.[56]

Protection and treatment

[edit]Protective clothing

[edit]Wearing pantyhose, full body lycra suits, dive skins, or wetsuits is an effective protection against box jellyfish stings.[61][unreliable source?] The pantyhose were formerly thought to work because of the length of the box jellyfish's stingers (nematocysts), but it is now known to be related to the way the stinger cells work. The stinging cells on a box jellyfish's tentacles are not triggered by touch, but by chemicals found on skin, which are not present on the hose's outer surface, so the jellyfish's nematocysts do not fire.[19]

First aid for stings

[edit]Once a tentacle of the box jellyfish adheres to skin, it pumps nematocysts with venom into the skin, causing the sting and agonizing pain. Flushing with vinegar is used to deactivate undischarged nematocysts to prevent the release of additional venom. A 2014 study reported that vinegar also increased the amount of venom released from already-discharged nematocysts; however, this study has been criticized on methodological grounds.[62]

Vinegar is made available on Australian beaches and in other places with venomous jellyfish.[56]

Removal of additional tentacles is usually done with a towel or gloved hand, to prevent secondary stinging. Tentacles can still sting if separated from the bell, or after the creature is dead. Removal of tentacles may cause unfired nematocysts to come into contact with the skin and fire, resulting in a greater degree of envenomation.[citation needed]

Although commonly recommended in folklore and even some papers on sting treatment,[63] there is no scientific evidence that urine, ammonia, meat tenderizer, sodium bicarbonate, boric acid, lemon juice, fresh water, steroid cream, alcohol, cold packs, papaya, or hydrogen peroxide will disable further stinging, and these substances may even hasten the release of venom.[64] Heat packs have been proven for moderate pain relief.[65] The use of pressure immobilization bandages, methylated spirits, or vodka is generally not recommended for use on jelly stings.[66][67][68][69]

Possible antidotes in humans

[edit]In 2011, researchers at the University of Hawaii announced that they had developed an effective treatment against the stings of Hawaiian box jellyfish by "deconstructing" the venom contained in their tentacles.[70] Its effectiveness was demonstrated in the PBS Nova episode "Venom: Nature's Killer", originally shown on North American television in February 2012.[71] Their research found that injected zinc gluconate prevented the disruption of red blood cells and reduced the toxic effects on the cardiac activity of research mice.[72][73] It was later found that copper gluconate was even more effective. A cream containing copper gluconate has been produced, to be applied to inhibit the injected venom; although it is used by U.S. military divers, evidence that it is effective in humans is only anecdotal.[74]

In April 2019, a team of researchers at the University of Sydney announced that they had found a possible antidote to Chironex fleckeri venom that would stop pain and skin necrosis if administered within 15 minutes of being stung. The research was the result of work done with CRISPR whole genome editing in which the researchers selectively deactivated skin-cell genes until they were able to identify ATP2B1, a calcium transporting ATPase, as a host factor supporting cytotoxicity. The research showed the therapeutic use of existing drugs targeting cholesterol in mice, although the efficacy of the approach had not been demonstrated in humans.[75]

References

[edit]- ^ Werner, B. (1973). "New investigations on systematics and evolution of the class Scyphozoa and the phylum Cnidaria" (PDF). Publications of the Seto Marine Biological Laboratory. 20: 35–61. doi:10.5134/175791.

- ^ "box jellyfish". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Box Jelly". Waikīkī Aquarium. 2013-11-20. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- ^ a b c d e f Avian, Massimo; Ramšak, Andreja (2021). "Chapter 10: Phylum Cnidaria: classes Scyphozoa, Cubozoa and Staurozoa". In Schierwater, Bernd; DeSalle, Rob (eds.). Invertebrate Zoology: A Tree of Life Approach. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-3582-1.

- ^ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Cubozoa". marinespecies.org. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- ^ Bentlage B, Cartwright P, Yanagihara AA, Lewis C, Richards GS, Collins AG (February 2010). "Evolution of box jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa), a group of highly toxic invertebrates". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 277 (1680): 493–501. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1707. PMC 2842657. PMID 19923131.

- ^ a b c d Lewis C, Bentlage B (2009). "Clarifying the identity of the Japanese Habu-kurage, Chironex yamaguchii, sp nov (Cnidaria: Cubozoa: Chirodropida)" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2030: 59–65. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2030.1.5.

- ^ a b Gershwin L, Gibbons M (2009). "Carybdea branchi, sp. nov., a new box jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa) from South Africa" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2088: 41–50. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2088.1.5. hdl:10566/369.

- ^ a b Gershwin, L. A.; Alderslade, P (2006). "Chiropsella bart n. sp., a new box jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa: Chirodropida) from the Northern Territory, Australia" (PDF). The Beagle, Records of the Museums and Art Galleries of the Northern Territory. 22: 15–21. doi:10.5962/p.287421. S2CID 51901195. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-09-27.

- ^ Holland, Brenden; Khramov, Marat; Crites, Jennifer. "Box Jellyfish (Cubozoa: Carybdeida) in Hawaiian Waters, and the First Record of Tripedalia cystophora in Hawai'i".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard, S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology, 7th edition. Cengage Learning. pp. 153–154. ISBN 978-81-315-0104-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 139–149. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- ^ Nilsson, Dan-E.; Gislén, Lars; Coates, Melissa M.; Skogh, Charlotta; Garm, Anders (May 2005). "Advanced optics in a jellyfish eye". Nature. 435 (7039): 201–205. doi:10.1038/nature03484. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ a b Garm, Anders; Oskarsson, Magnus; Nilsson, Dan-Eric (2011-05-10). "Box Jellyfish Use Terrestrial Visual Cues for Navigation". Current Biology. 21 (9): 798–803. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.054. ISSN 0960-9822.

- ^ Garm, A; O'Connor, M; Parkefelt, L; Nilsson, D (October 15, 2007). "Visually guided obstacle avoidance in the box jellyfish Tripedalia cystophora and Chiropsella bronzie". Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (20).

- ^ Garm, A.; Andersson, F.; Nilsson, Dan-E. (2008-03-01). "Unique structure and optics of the lesser eyes of the box jellyfish Tripedalia cystophora". Vision Research. 48 (8): 1061–1073. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2008.01.019. ISSN 0042-6989.

- ^ a b Skogh C, Garm A, Nilsson DE, Ekström P (December 2006). "Bilaterally symmetrical rhopalial nervous system of the box jellyfish Tripedalia cystophora". Journal of Morphology. 267 (12): 1391–405. doi:10.1002/jmor.10472. PMID 16874799.

- ^ Nilsson DE, Gislén L, Coates MM, Skogh C, Garm A (May 2005). "Advanced optics in a jellyfish eye". Nature. 435 (7039): 201–5. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..201N. doi:10.1038/nature03484. PMID 15889091. S2CID 4418085.

- ^ a b c d "Box Jellyfish, Box Jellyfish Pictures, Box Jellyfish Facts". NationalGeographic.com. 10 September 2010. Archived from the original on January 24, 2010. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ^ Williamson JA, Fenner PJ, Burnett JW, Rifkin J, eds. (1996). Venomous and poisonous marine animals: a medical and biological handbook. Surf Life Saving Australia and University of New North Wales Press Ltd. ISBN 0-86840-279-6.[page needed]

- ^ Gershwin, L (2006). "Nematocysts of the Cubozoa" (PDF). Zootaxa (1232): 1–57.

- ^ Straehler-Pohl, I.; G.I. Matsumoto; M.J. Acevedo (2017). "Recognition of the Californian cubozoan population as a new species Carybdea confusa n. sp. (Cnidaria, Cubozoa, Carybdeida)". Plankton Benthos Res. 12 (2): 129–138. doi:10.3800/pbr.12.129.

- ^ Gershwin L (2009). "Staurozoa, Cubozoa, Scyphozoa (Cnidaria)". In Gordon D (ed.). New Zealand Inventory of Biodiversity. Vol. 1: Kingdom Animalia.[page needed]

- ^ Pongsakchat, Vanida; Kidpholjaroen, Pattaraporn (2020-06-28). "The Statistical Distributions of PM2.5 in Rayong and Chonburi Provinces, Thailand". Asian Journal of Applied Sciences. 8 (3). doi:10.24203/ajas.v8i3.6153. ISSN 2321-0893.

- ^ "Box Jelly". University of Hawai'i - Waikiki Aquarium. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Coates, Melissa M. (2003-08-01). "Visual Ecology and Functional Morphology of Cubozoa (Cnidaria)". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 43 (4): 542–548. doi:10.1093/icb/43.4.542. ISSN 1540-7063. PMID 21680462.

- ^ Ames, Cheryl Lewis; Macrander, Jason (2016). "Evidence for an Alternative Mechanism of Toxin Production in the Box Jellyfish Alatina alata". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 56 (5): 973–988. ISSN 1540-7063. JSTOR 26370052.

- ^ Aungtonya, Charatsee; Xiao, Jie; Zhang, Xuelei; Wutthituntisil, Nattanon (October 2018). "The genus Chiropsoides (Chirodropida: Chiropsalmidae) from the Andaman Sea, Thai waters". Acta Oceanologica Sinica. 37 (10): 119–125. doi:10.1007/s13131-018-1311-4. ISSN 0253-505X.

- ^ a b c d Bolte, Brett; Goldsbury, Julie; Jerry, Dean; Kingsford, Michael (2020-06-18). "Validation of eDNA as a viable method of detection for dangerous cubozoan jellyfish". doi:10.22541/au.159248732.24076157. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ a b c d Morrissey, Scott J.; Jerry, Dean R.; Kingsford, Michael J. (2022-12-19). "Genetic Detection and a Method to Study the Ecology of Deadly Cubozoan Jellyfish". Diversity. 14 (12): 1139. doi:10.3390/d14121139. ISSN 1424-2818.

- ^ a b c Minamoto, Toshifumi; Fukuda, Miho; Katsuhara, Koki R.; Fujiwara, Ayaka; Hidaka, Shunsuke; Yamamoto, Satoshi; Takahashi, Kohji; Masuda, Reiji (2017-02-28). "Environmental DNA reflects spatial and temporal jellyfish distribution". PLOS ONE. 12 (2): e0173073. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0173073. hdl:20.500.14094/90003938. ISSN 1932-6203.

- ^ Pitt, Kylie A.; Lucas, Cathy H. (2013). Jellyfish Blooms. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 280. ISBN 978-94-007-7015-7.

- ^ "Australian Box Jellyfish: 15 Fascinating Facts". Travel NQ. 2014-12-14. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- ^ a b c Lewis, Cheryl; Long, Tristan A. F. (2005-06-01). "Courtship and reproduction in Carybdea sivickisi (Cnidaria: Cubozoa)". Marine Biology. 147 (2): 477–483. doi:10.1007/s00227-005-1602-0. ISSN 1432-1793.

- ^ Avian, Massimo; Ramšak, Andreja (2021). "Chapter 10: Phylum Cnidaria: classes Scyphozoa, Cubozoa and Staurozoa". In Schierwater, Bernd; DeSalle, Rob (eds.). Invertebrate Zoology: A Tree of Life Approach. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-3582-1.

- ^ Rodríguez, J. C. (2015). "Anatomy associated with the reproductive behavior of Cubozoa". Institute of Biosciences of the University of Sao Paulo. Sao Paulo.

- ^ García-Rodríguez, Jimena; Ames, Cheryl Lewis; Jaimes-Becerra, Adrian; Tiseo, Gisele Rodrigues; Morandini, André Carrara; Cunha, Amanda Ferreira; Marques, Antonio Carlos (July 2023). "Histological Investigation of the Female Gonads of Chiropsalmus quadrumanus (Cubozoa: Cnidaria) Suggests Iteroparous Reproduction". Diversity. 15 (7): 816. doi:10.3390/d15070816. ISSN 1424-2818.

- ^ a b c d e f Kayal, Ehsan; Bentalge, Bastian; Collins, Allen G (June 6, 2016), "Insights into the transcriptional and translational mechanisms of linear organellar chromosomes in the box jellyfish Alatina alata (Cnidaria: Medusozoa: Cubozoa)", RNA Biology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 799–809, doi:10.1080/15476286.2016.1194161, PMC 5013998, PMID 27267414

- ^ Santander, Mylena D.; Maronna, Maximiliano M.; Ryan, Joseph F.; Andrade, Sónia C S. (2022). "The state of Medusozoa genomics: Current evidence and future challenges". GigaScience. 11. doi:10.1093/gigascience/giac036. PMC 9112765. PMID 35579552.

- ^ "Girl survives sting by world's deadliest jellyfish". Daily Telegraph. London. 27 April 2010. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Hunt, lle (3 July 2021). "'It looked like an alien, with all its tentacles wrapped around her': are jellyfish here to ruin your summer holiday?". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Pearn, J. H. (1990). "Flecker, Hugo (1884–1957)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 14. Melbourne University Press. pp. 182–184. ISBN 978-0-522-84717-8.

- ^ "Beach community in shock after teenager dies from box jellyfish sting". ABC News. 2022-02-27. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ a b Centre for Disease Control (November 2012). "Chironex fleckeri" (PDF). Northern Territory Government Department of Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-07-09. Retrieved 2018-11-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Teenage boy dies from box jellyfish sting in Cape York — the first death from the animal in 15 years". www.abc.net.au. 2021-03-04. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ a b Daubert, G. P. (2008). "Cnidaria Envenomation". eMedicine.

- ^ Maddison, Melissa (26 February 2022). "Teenager dies from box jellyfish sting at Eimeo Beach near Mackay". ABC News.

- ^ "Queensland teenager dies from box jellyfish sting in first fatality from the animal in 15 years". The Guardian. 2021-03-04. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ "Queensland boy dies after being stung by box jellyfish while swimming". 7NEWS.com.au. 2021-03-04. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ^ Fenner PJ, Hadok JC (October 2002). "Fatal envenomation by jellyfish causing Irukandji syndrome". The Medical Journal of Australia. 177 (7): 362–3. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04838.x. PMID 12358578. S2CID 2157752.

- ^ Gershwin, L (2007). "Malo kingi: A new species of Irukandji jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa: Carybdeida), possibly lethal to humans, from Queensland, Australia". Zootaxa. 1659: 55–68. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1659.1.2.

- ^ a b Little M, Mulcahy RF (1998). "A year's experience of Irukandji envenomation in far north Queensland". The Medical Journal of Australia. 169 (11–12): 638–41. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb123443.x. PMID 9887916. S2CID 37058912.

- ^ "Jellyfish: A Dangerous Ocean Organism of Hawaii". Archived from the original on 2001-11-17. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "Hanauma Bay closed for second day due to box jellyfish". Archived from the original on 2021-01-02. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ Fenner PJ, Williamson JA (1996). "Worldwide deaths and severe envenomation from jellyfish stings". The Medical Journal of Australia. 165 (11–12): 658–61. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb138679.x. PMID 8985452. S2CID 45032896.

- ^ a b c Fenner PJ (1997). The Global Problem of Cnidarian (Jellyfish) Stinging (PhD Thesis). London: London University. OCLC 225818293.[page needed]

- ^ "Box jellyfish warning in Ko Phangan". Bangkok Post. 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Jellyfish warning for travellers swimming in Thailand". Tourism Authority of Thailand Newsroom. TAT. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ "Box jellyfish sting kills woman in Koh Phangan - Phuket Gazette". phuketgazette.net. 3 August 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "Jellyfish Kill German Tourist on Koh Samui". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-07.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Jason (June 10, 2010). "Use Pantyhose to Protect Yourself from Jellyfish Stings". Lifehacker. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ Wilcox, Christie (9 April 2014). "Should we stop using vinegar to treat box jelly stings? Not yet—Venom experts weigh in on recent study". Science Sushi. Discover Magazine Blogs. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Zoltan TB, Taylor KS, Achar SA (June 2005). "Health issues for surfers". American Family Physician. 71 (12): 2313–7. PMID 15999868.

- ^ Fenner P (2000). "Marine envenomation: An update – A presentation on the current status of marine envenomation first aid and medical treatments". Emergency Medicine Australasia. 12 (4): 295–302. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2026.2000.00151.x.

- ^ Taylor, G. (2000). "Are some jellyfish toxins heat labile?". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 30 (2). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Archived from the original on 2009-01-23. Retrieved 2013-11-15.

- ^ Hartwick R, Callanan V, Williamson J (January 1980). "Disarming the box-jellyfish: nematocyst inhibition in Chironex fleckeri". The Medical Journal of Australia. 1 (1): 15–20. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1980.tb134566.x. PMID 6102347. S2CID 204054168.

- ^ Seymour J, Carrette T, Cullen P, Little M, Mulcahy RF, Pereira PL (October 2002). "The use of pressure immobilization bandages in the first aid management of cubozoan envenomings". Toxicon. 40 (10): 1503–5. doi:10.1016/S0041-0101(02)00152-6. PMID 12368122.

- ^ Little M (June 2002). "Is there a role for the use of pressure immobilization bandages in the treatment of jellyfish envenomation in Australia?". Emergency Medicine. 14 (2): 171–4. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2026.2002.00291.x. PMID 12164167.

- ^ Pereira PL, Carrette T, Cullen P, Mulcahy RF, Little M, Seymour J (2000). "Pressure immobilisation bandages in first-aid treatment of jellyfish envenomation: current recommendations reconsidered". The Medical Journal of Australia. 173 (11–12): 650–2. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb139373.x. PMID 11379519. S2CID 27025420.

- ^ UHMedNow, "Angel Yanagihara's box jellyfish venom research leads to sting treatment" Archived 2012-10-22 at the Wayback Machine, March 4, 2011

- ^ PBS Nova, Venom: Nature's Killer (transcript)

- ^ Yanagihara AA, Shohet RV (12 December 2012). "Cubozoan venom-induced cardiovascular collapse is caused by hyperkalemia and prevented by zinc gluconate in mice". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e51368. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...751368Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051368. PMC 3520902. PMID 23251508.

- ^ Wilcox, Christie (12 December 2012). "Don't Pee On It: Zinc Emerges As New Jellyfish Sting Treatment". scientificamerican.com. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Law, Yao-Hua (8 November 2018). "Jellyfish almost killed this scientist. Now, she wants to save others from their fatal venom". Science - AAAS.

- ^ Lau, Man-Tat; Manion, John; Littleboy, Jamie B.; Oyston, Lisa; Khuong, Thang M.; Wang, Qiao-Ping; Nguyen, David T.; Hesselson, Daniel; Seymour, Jamie E.; Neely, G. Gregory (April 30, 2019). "Molecular dissection of box jellyfish venom cytotoxicity highlights an effective venom antidote". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1655. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1655L. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09681-1. PMC 6491561. PMID 31040274. 1655.