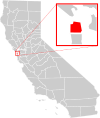

Mission District, San Francisco

Mission District

The Mission | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 37°46′N 122°25′W / 37.76°N 122.42°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City and county | |

| Government | |

| • Supervisor | Hillary Ronen (D) |

| • Assemblymember | Matt Haney (D)[1] |

| • State senator | Scott Wiener (D)[1] |

| • U. S. rep. | Nancy Pelosi (D)[2] |

| Area | |

| • Land | 1.481 sq mi (3.84 km2) |

| Population (2019)[3] | |

• Total | 44,541 |

| • Density | 30,072/sq mi (11,611/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−08:00 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−07:00 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 94103, 94110 |

| Area codes | 415/628 |

The Mission District (Spanish: Distrito de la Misión),[4] commonly known as the Mission (Spanish: La Misión),[5] is a neighborhood in San Francisco, California. One of the oldest neighborhoods in San Francisco, the Mission District's name is derived from Mission San Francisco de Asís, built in 1776 by the Spanish.[6] The Mission is historically one of the most notable centers of the city's Chicano/Mexican-American community.

Location and climate

[edit]The Mission District is located in east-central San Francisco. It is bordered to the east by U.S. Route 101, which forms the boundary between the eastern portion of the district, known as "Inner Mission", and its eastern neighbor, Potrero Hill. Sanchez Street separates the neighborhood from Eureka Valley (containing the sub-district known as "the Castro") to the north west and Noe Valley to the south west. The part of the neighborhood from Valencia Street to Sanchez Street, north of 20th Street, is known as the "Mission Dolores" neighborhood. South of 20th Street towards 22nd Street, and between Valencia and Dolores Streets is a distinct neighborhood known as Liberty Hill.[7] Cesar Chavez Street (formerly Army Street) is the southern border; across Cesar Chavez Street is the Bernal Heights neighborhood. North of the Mission District is the South of Market neighborhood, bordered roughly by Duboce Avenue and the elevated highway of the Central Freeway which runs above 13th Street.

The principal thoroughfare of the Mission District is Mission Street. South of the Mission District, along Mission Street, are the Excelsior and Crocker-Amazon neighborhoods, sometimes referred to as the "Outer Mission" (not to be confused with the actual Outer Mission neighborhood). The Mission District is part of San Francisco's supervisorial districts 6, 9 and 10.

The Mission is often warmer and sunnier than other parts of San Francisco. The microclimates of San Francisco create a system by which each neighborhood can have different weather at any given time, although this phenomenon tends to be less pronounced during the winter months. The Mission's geographical location insulates it from the fog and wind from the west. This climatic phenomenon becomes apparent to visitors who walk downhill from 24th Street in the west from Noe Valley (where clouds from Twin Peaks in the west tend to accumulate on foggy days) towards Mission Street in the east, partly because Noe Valley is on higher ground whereas the Inner Mission is at a lower elevation.[8]

The Mission includes four recognized sub-districts.[9] The northeastern quadrant, adjacent to Potrero Hill is known as a center for high tech startup businesses including some chic bars and restaurants. The northwest quadrant along Dolores Street is famous for Victorian mansions and the popular Dolores Park at 18th Street. Two main commercial zones, known as the Valencia corridor (Valencia St, from about 15th to 22nd) and the 24th Street corridor known as Calle 24[10][11] in the south central part of the Mission District are both very popular destinations for their restaurants, bars, galleries and street life.

History

[edit]Native peoples and Spanish colonization

[edit]Prior to the arrival of Spanish missionaries, the area which now includes the Mission District was inhabited by the Ohlone people who populated much of the San Francisco bay area. The Yelamu Indians inhabited the region for over 2,000 years. Spanish missionaries arrived in the area during the late 18th century. They found these people living in two villages on Mission Creek. It was here that a Spanish priest named Father Francisco Palóu founded Mission San Francisco de Asís on June 29, 1776. The Mission was moved from the shore of Laguna Dolores to its current location in 1783.[12] Franciscan friars are reported to have used Ohlone slave labor to complete the Mission in 1791.[13] This period marked the beginning of the end of the Yelamu culture. The Indian population at Mission Dolores dropped from 400 to 50 between 1833 and 1841.

San Francisco's southern expansion

[edit]

Ranchos owned by Spanish-Mexican families such as the Valenciano, Guerrero, Dolores, Bernal, Noé and De Haro continued in the area, separated from the town of Yerba Buena, later renamed San Francisco (centered around Portsmouth Square) by a two-mile wooden plank road (later paved and renamed Mission Street).

The lands around the nearly abandoned mission church became a focal point of raffish attractions[14] including bull and bear fighting, horse racing, baseball and dueling. A famous beer parlor resort known as The Willows was located along Mission Creek just south of 18th Street between Mission and San Carlos streets.[15] From 1865 to 1891, a large conservatory and zoo known as Woodward's Gardens covered two city blocks bounded by Mission, Valencia, 13th and 15th streets.[16] In the decades after the Gold Rush, the town of San Francisco quickly expanded, and the Mission lands were developed and subdivided into housing plots for working-class immigrants, largely German, Irish, and Italian,[14] and also for industrial uses.

As the city grew in the decades following the Gold Rush, the Mission District became home to the first professional baseball stadium in California, opened in 1868 and known as Recreation Grounds, seating 17,000 people, which was located at Folsom and 25th streets; a portion of the grounds remain as present day Garfield Square.[17] Also, in the 20th century, the Mission District was home to two other baseball stadiums: Recreation Park, located at 14th and Valencia, and Seals Stadium, located at 16th and Bryant, with both these stadiums being used by the baseball team named after the Mission District known as the Mission Reds and the San Francisco Seals.

Irish immigrants moved into the Mission in the late 19th century. The Irish made their mark not only by working for the city government but by helping build the Catholic schools in the Mission District.

Earthquake and population shifts

[edit]

During California's early statehood period, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, large numbers of Irish and German immigrant workers moved into the area. Around 1900, the Mission District was still one of San Francisco's least densely populated areas, with most of the inhabitants being white families from the working class and lower middle class who lived in single-family houses and two-family flats.[18] Development and settlement intensified after the 1906 earthquake, as many displaced businesses and residents moved into the area, making Mission Street a major commercial thoroughfare.

In 1901, the city of San Francisco changed laws and forbade burials in the city, which helped form the nearby city of Colma.[19] During the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, a single working water hydrant (the so-called 'Golden Fire Hydrant') saved the Mission District from being burned down by massive fires sparked by the earthquake.[20] In the 1910s, the roads into Colma were not well maintained and it was a common practice to use the street cars to move bodies.[21] Valencia Street became a location of many mortuaries and funeral homes during this time due to the quick access to Colma by street car.[21]

In 1926, the Polish community of San Francisco converted a church at 22nd and Shotwell streets and opened its doors as the Polish Club of San Francisco; it is referred to today as the "Dom Polski", or Polish Home. The Irish American community made its mark on the area during this time, with notable residents such as etymologist Peter Tamony calling the Mission home.

During the 1940s to 1960s, a large number of Mexican immigrants moved into the area—displaced from an earlier "Mexican Barrio" located on Rincon Hill, demolished in order to create the western landing of the Bay Bridge—initiating white flight and giving the Mission a heavily Chicano/Latino character for which it continues to be known today. Central American immigration starting in the 1960s has contributed to a Central American presence outnumbering those of Mexican descent.[citation needed]

1970s–1990s

[edit]

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Chicano/Latino population in the western part of the Mission (including the Valencia Corridor) declined somewhat and more middle-class young people moved in, including gay and lesbian people (alongside the existing LGBTQ Latino population).[18] One political movement during the early 70s emerged in the community as seven young Latino men known as Los Siete de la Raza from the Mission District were being charged for the 1969 murder of a San Francisco police officer.[22] The community got together as these young men were standing up to what was being said about them and were determined to be heard. The people around the Mission District knew these seven young individuals as change-makers; they were actively trying to get more people from the Mission District to go to college,[23] they also worked with organizations that helped make the community better for Latino people which included a free bilingual services through Centro de Salud, which ultimately led other local hospitals to do the same. They were also involved in a free breakfast program, a community newspaper, and its main program, the "Los Siete" Defense Committee.[24]

From the mid-1970s through the 1980s, the Valencia Street corridor included one of the most concentrated and visible lesbian neighborhoods in the United States.[18] The Women's Building, Osento Bathhouse, Old Wives Tales bookstore, Artemis Cafe, Amelia's and The Lexington Club were part of that community.[25][26][27]

In the late 1970s and early 1980s the Valencia Street corridor had a lively punk nightlife featuring the bands The Offs, The Avengers, the Dead Kennedys, Flipper, and several clubs including The Offensive, The Deaf Club, Valencia Tool & Die and The Farm. The former fire station on 16th Street, called the Compound, sported what was commonly referred to as "the punk mall", an establishment that catered to punk style and culture. On South Van Ness, Target Video and Damage magazine were located in a three-story warehouse. The former Hamms brewery was converted to a punk living/rehearsal building, popularly known as The Vats. The neighborhood was dubbed "the New Bohemia" by the San Francisco Chronicle in 1995.[28]

In the 1980s and 1990s, the neighborhood received a higher influx of immigrants and refugees from Central America, South America, the Middle East and even the Philippines and former Yugoslavia, fleeing civil wars and political instability at the time. These immigrants brought in many Central American banks and companies which would set up branches, offices, and regional headquarters on Mission Street.

1990s–present

[edit]From the late 1990s through the 2010s, and especially during the dot-com boom, young urban professionals moved into the area. It is widely believed that their movement initiated gentrification, raising rent and housing prices.[29] A number of Latino American middle-class families as well as artists moved to the Outer Mission area, or out of the city entirely to the suburbs of East Bay and South Bay area. Despite rising rent and housing prices, many Mexican and Central American immigrants continue to reside in the Mission, although the neighborhood's high rents and home prices have led to the Latino population dropping by 20% over the decade until 2011.[30] However, in 2008 the Mission still had a reputation of being artist-friendly.[31]

In 2000, the Mission District's Latino population was at 60%. By 2015 it had dropped to 48%; a city-funded research study that year predicted a decline to 31 percent by 2025.[32] However, the Mission remains the cultural nexus and epicenter of San Francisco's Mexican/Chicano, and to a lesser extent, the Bay Area's Nicaraguan, Salvadoran and Guatemalan community. While Mexican, Salvadoran, and other Latin American businesses are pervasive throughout the neighborhood, residences are not evenly distributed. Of the neighborhood's Chicano/Latino residents, most live on the eastern and southern sides. The western and northern sides of the neighborhood are more affluent and white.[33] As of 2017, the northern part of the Mission, together with the nearby Tenderloin, is home to a Mayan-speaking community, consisting of immigrants who have been arriving since the 1990s from Mexico's Yucatán region.[34] Their presence is reflected in the Mayan-language name of In Chan Kaajal Park, opened in 2017 north of 17th Street between Folsom and Shotwell streets.[34]

Landmarks and features

[edit]

Mission Dolores, the eponymous former mission located at the far western border of the neighborhood on Dolores Street, continues to operate as a museum and as a California Historical Landmark, while the newer basilica built and opened next to it in 1918 continues to have an active congregation.

Dolores Park (Mission Dolores Park) is the largest park in the neighborhood, and one of the most popular parks in the city. Dolores Park is near Mission Dolores. Across from Dolores Park is Mission High School, built in 1927 in the Mediterranean Revival style.

The San Francisco Armory is a castle-like building located at 14th and Mission that was built as an armory for the U.S. Army and California National Guard. It served as the headquarters of the 250th Coast Artillery from 1923 through 1944, and of the 49th Infantry, also known as the 49ers, during the Cold War.

Food

[edit]The Mission District is also famous and influential for its restaurants. Dozens of taquerías are located throughout the neighborhood, showcasing a localized styling of Mexican food. San Francisco is the original home of the Mission burrito.[35] There is also a high concentration of Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Nicaraguan restaurants there as well as a large number of street food vendors.[36] In the last couple decades a number of Mission restaurants have gained national attention, most notably the five restaurants that have received Michelin stars for 2017: Commonwealth, Lazy Bear, Aster, Californios, and Al's Place.[37] A large number of other restaurants are also popular, including: Mission Chinese Food, Western Donut, Bar Tartine, La Taqueria, Papalote, Foreign Cinema on Mission Street, and Delfina on 18th.[38][39] La Mejor Bakery, a San Francisco legacy business, is located in the Mission.[40]

Art scene

[edit]Numerous Latino artistic and cultural institutions are based in the Mission. These organizations were founded during the social and cultural renaissance of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Latino community artists and activists of the time organized to create community-based arts organizations that were reflective of the Latino aesthetic and cultural traditions. The Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts, established by Latino artists and activists, is an art space that was founded in 1976 in a space that was formerly a furniture store. The local bilingual newspaper El Tecolote was founded in 1970. The Mission's Galería de la Raza, founded by local artists active in el Movimiento (the Chicano civil rights movement), is a nationally recognized arts organization, also founded during this time of cultural and social renaissance in the Mission, in 1971. Late May, the city's annual Carnaval festival and parade marches down Mission Street. Inspired by the festival in Rio de Janeiro, it is held in late May instead of the traditional late February to take advantage of better weather. The first Carnaval in San Francisco happened in 1978, with less than 100 people dancing in a parade that went around Precita Park. Alejandro Murguía (born 1949) is an American poet, short story writer, editor and filmmaker who was named San Francisco Poet Laureate in 2012. He is known for his writings about the Mission District where he has been a long-time resident.

Due to the existing cultural attractions, formerly less expensive housing and commercial space, and the high density of restaurants and drinking establishments, the Mission is a magnet for young people. An independent arts community also arose and, since the 1990s, the area has been home to the Mission School art movement. Many studios, galleries, performance spaces, and public art projects are located in the Mission, including 1890 Bryant St Studios, Southern Exposure, Art Explosion Studios, City Art Collective Gallery, Artists' Television Access, Savernack Street, and the oldest, alternative, not-for-profit art space in the city of San Francisco, Intersection for the Arts. There are more than 500 Mission artists listed on Mission Artists United site put together by Mission artists. The Roxie Theater, the oldest continuously operating movie theater in San Francisco, is host to repertory and independent films as well as local film festivals. Poets, musicians, emcees, and other artists sometimes gather on the southwest corner of the 16th and Mission intersection to perform.[41] Dance Mission Theater is a nonprofit performance venue and dance school in the neighborhood as well.[42]

Murals

[edit]Throughout the Mission walls and fences are decorated with murals initiated by the Chicano Art Mural Movement of the 1970s[43] and inspired by the traditional Mexican paintings. Some of the more significant mural installations are located on Balmy Alley and Clarion Alley. Many of these murals have been painted or supported by the Precita Eyes muralist organization.

Music scene

[edit]Someone called my name

You know, I turned around to see

It was midnight in the Mission

and the bells were not for me

There's some satisfaction

in the San Francisco rain

No matter what comes down

the Mission always looks the same

Come again

Walking along in the Mission in the rain

The Mission is rich in musical groups and performances. Mariachi bands play in restaurants throughout the district, especially in the restaurants congregated around Valencia and Mission in the northeast portion of the district. Carlos Santana spent his teenage years in the Mission, graduating from Mission High School in 1965. He often returned to the neighborhood, including for a live concert with his band Santana that was recorded in 1969,[45] and for the KQED documentary "The Mission" filmed in 1994.[46]

The locally inspired song "Mission in the Rain" by Robert Hunter and Jerry Garcia appeared on Garcia's solo album Reflections, and was played by the Grateful Dead five times in concert in 1976.[47]

Classical music is heard in the concert hall of the Community Music Center on Capp Street.[48]

The area is also home to Afrolicious, and Dub Mission, a formerly weekly reggae/dub party started in 1996, and over the years has brought many reggae and dub musicians to perform there.

The Mission District also has a Hip-hop/Rap music scene. Other prominent musicians and musical personalities include alternative rock bands and musicians Luscious Jackson, Faith No More, The Looters, Primus, Chuck Prophet & The Mission Express, Beck, and Jawbreaker.

Visual artists

[edit]Some well-known artists associated with the Mission District include:

- Benjamin Bratt (born 1963), actor, film producer

- Peter Bratt (born 1962), film director, producer[49]

- Craig Baldwin (born 1952), experimental filmmaker

- Chuy Campusano (1944–1997), Chicano muralist

- Rolando Castellón (born 1937), painter, author, art historian, and curator.

- Laurie Toby Edison (born 1942), photographer

- Rupert García (born 1941), artist and professor

- Ricardo Gouveia (born 1966), also known as "Rigo 23", painter, sculptor, and muralist

- David Ireland (1930–2009), sculptor, installation artist, co-founder of Capp Street Project

- Chris Johanson (born 1968), painter, muralist and street artist

- Margaret Kilgallen (1967–2001), painter, printmaker, and graffiti artist

- Lil Tuffy, poster art, serigraph printmaker and designer

- Carlos Loarca (born 1939), painter, muralist[50][51]

- Yolanda López (1942–2021), painter, printmaker, educator, and film producer.

- Ralph Maradiaga (1934–1985), artist, curator, photographer, printmaker, teacher, and filmmaker

- Barry McGee (born 1966), also known as "Twist", painter and graffiti artist

- Ruby Neri (born 1970), painter, sculptor, and graffiti artist

- Sirron Norris, illustrator, and muralist[52]

- Dan Plasma, graffiti artist, muralist[53]

- Rex Ray (1956–2015), graphic designer and collage artist

- Peter Rodríguez (1926–2016), artist, curator, and museum director; founder of the Mexican Museum

- Spain Rodriguez (1940–2002), underground cartoonist.[54]

- Michael V. Rios, painter, designer, and muralist[55]

- Pico Sanchez, painter, printmaker[56]

- Adam Savage (born 1967), television personality, model maker, designer, fabricator

- Dori Seda (1951–1988), cartoonist, painter

- Xavier Viramontes (born 1947), printmaker[57][58]

- Scott Williams (born 1956) stencil artist, muralist[59]

- Megan Wilson, conceptual, installation, and muralist

- René Yañez (1942–2018), painter, assemblage artist, performance artist, curator and community activist.

Arts organizations

[edit]- Acción Latina[60]

- Art Explosion Studios[61]

- Artists' Television Access (ATA)

- Brava Theater

- City Art Collective Gallery

- Creativity Explored

- Eth-Noh-Tec, Kinetic Story Theater Eth-Noh-Tec (storytelling kinetic theater)

- Gray Area

- Kadist

- Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts

- Project Artaud[62]

- Root Division, from 2002 until 2015

- Ruth's Table

- San Francisco Community Music Center

- Savernack Street

- Southern Exposure

- Theatre of Yugen at NOHspace

- The Lab[63]

- The Marsh

- 1890 Bryant St Studios

- 500 Capp Street

Festivals, parades and fairs

[edit]

- Carnaval – The major event of the year occurring each Memorial Day weekend is the Mission's Carnaval celebration.[64]

- 24th Street Fair – In March of each year a street fair is held along the 24th Street corridor.

- San Francisco Food Fair – Annually, for several years recently, food trucks and vendor booths have sold food to tens of thousands of people along Folsom Street adjacent to La Cochina on the third weekend in September.[65]

- Cesar Chavez Holiday Parade – The second weekend of April is marked by a parade and celebration along 24th Street in honor of Cesar Chavez.[66]

- Transgender and Dyke Marches – On the Fridays and Saturdays of the fourth weekend of June there are major celebrations of the transgender and dyke communities located at Dolores Park, followed by a march in the evenings along 18th and Valencia streets.[67][68]

- Sunday Streets – Twice each year, typically in May and October, Valencia, Harrison and 24th Streets are closed to automobile traffic and opened to pedestrians and bicyclists on Sunday as part of the Sunday Streets program.[69]

- Day of the Dead – Each year on November 2, a memorial procession and celebration of the dead (Dia de los Muertos) occurs on Harrison and 24th Street with a gathering of memorials in Garfield Square.[70][71]

- First Friday – Monthly on the evening of the first Friday, a food and art crawl including a procession of low rider car clubs and samba dancers occurs along 24th Street from Potrero to Mission Streets.[72]

- Open Studios – On the first weekend of October, the ArtSpan organization arranges a district-wide exhibit of Mission District artists studios.[73]

- Hunky Jesus Contest – Until 2014, annually on Easter Sunday the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence held an Easter Sunday celebration including a Hunky Jesus Contest in Dolores Park. In 2014, Hunky Jesus moved to Golden Gate Park due to construction at Dolores Park.[74][75]

- Rock Make Street Festival – Annually for four years the Rock Make organization sponsors a music and arts festival in September on Treat and 18th Streets in the Mission.[76]

- LitCrawl – Annually on the third Saturday of October as part of the LitQuake, a literature festival, hundreds of book and poetry readings are held at bars and bookstores throughout the Mission.[77]

- Party on Block 18 – Bi-annual summer benefit for The Woman's Building and other local non-profits. The day-long street party is located on 18th Street between Dolores and Guerrero Streets.[78][79]

- Clarion Alley Block Party – Eleven years annually, a block party on the Clarion mural alley, fourth weekend in October.[80]

- Remembering 1906 – Annually for 108 years there has been a gathering and ceremonial gold repainting ceremony of the fire hydrant located at Church and 20th streets in honor of the only working fire hydrant that allowed the cessation of the fire following the 1906 earthquake.[81]

Media

[edit]The Mission District is covered by three free bilingual newspapers. El Tecolote is biweekly and has online articles.[82] Mission Local is predominantly an online news site but does publish a semiannual printed paper.[83] El Reportero is a weekly newspaper that also has an online site.[84]

Transit

[edit]The neighborhood is served by the BART rail system with stations on Mission Street at 16th Street and 24th Street, by Muni bus numbers 9, 9R, 12, 14, 14R, 22, 27, 33, 48, 49, 67, and along the western edge by the J Church Muni Metro line, which runs down Church Street and San Jose Avenue.

Gentrification

[edit]The Mission District is a historic transit hub for the Chicano and the Latino community, especially on the 16th Street BART Plaza.[85] An atmosphere like a public market with live music and food trucks, it is also a commuting point for public transportation, which primarily serves low-income working-class people. The majority of the residents in the Mission District are of minority and low-income families and use this useful and open hub for gatherings and doing local businesses such as food trucks.[85] However, because of the Dot-Com Boom that occurred in the 1990s and the rise of technology and social media, major technology companies such as Google and Facebook have moved their offices to such places as Silicon Valley, in the South Bay, that have now become the hot spot for tech companies.[86] The Mission has felt the downstream effects of this demographic shift acutely. The intense surge in demand for housing and low supply of available housing has placed upward pressure on rents in transit hubs like the Mission, leading to gentrification and the displacement of families and small businesses. However, many residents protested and engaged in activism. They created a group called the "Plaza 16 Coalition" in response to the gentrification and the new zoning law, the "Eastern Neighborhoods Plan".[87] They advocate for affordable housing, opposing market-rate developments and the luxury developments.

Education

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2020) |

San Francisco Unified School District operates public schools. Schools in the Mission District include:

- John O'Connell High School[88]

- Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8 Community School[89]

- Bryant Elementary School[90]

- César Chávez Elementary School[91]

- Leonard R. Flynn Elementary School[92]

- Marshall Elementary School[93]

- George R. Moscone Elementary School - As of 2020[update] it had 350 students.[94]

- Zaida T. Rodriguez Early Education School[95]

- Hilltop Special Service Center (special school for grades 7–12)[96]

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of San Francisco operates St. Peter's Catholic School, which opened in 1878. Previously its students were Irish or Italian American, but by 2014 95% of the student body was Latino and about two thirds were categorized as economically disadvantaged. Enrollment was once around 600 but by 2014 was around 300 due to gentrification. Its yearly per-student cost was $5,800 while yearly tuition, the lowest in the archdiocese, was $3,800.[97]

See also

[edit]- 826 Valencia

- Intersection for the Arts

- The Lexington Club

- Tartine – local bakery

- The Redstone Building

Further reading

[edit]- Hooper, Bernadette (2006). San Francisco's Mission District. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-4657-7.

- Mirabal, Nancy Raquel, "Geographies of Displacement: Latinas/os, Oral History, and the Politics of Gentrification in San Francisco's Mission District", Public Historian, 31 (May 2009), 7–31.

- Heins, Marjorie "Strictly Ghetto Property: The Story of Los Siete de La Raza" Ramparts Press; first edition (1972)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ^ "California's 11th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ a b "Mission District (The Mission) neighborhood in San Francisco, California (CA), 94103, 94110 subdivision profile". Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ "Quiénes Somos". Mission Local.

- ^ Telemundo Área de la Bahía - Investigan tiroteo en La Misión de San Francisco

- ^ Daily Alta California newspaper, Oct 7, 1854, page 1 column 4

- ^ Liberty Hill Neighborhood Association Archived September 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Libertyhillsf.org.

- ^ San Francisco Planning Department (2005). "Inner Mission North 1853–1943 Context Statement, 2005" (PDF). Cultural Resources Survey. pp. 9, 10, 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 4, 2006. Retrieved November 27, 2006.

- ^ SFGate. "Bay Area Neighborhoods". Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ Lagos, Marisa (April 22, 2014). "A mission for the Mission: Preserve Latino legacy for future". SF Gate. Hearst Newspapers. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ "Calle 24 Latino Cultural District". SF Heritage. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ Alejandrino, Simon Velasquez (Summer 2000). "Gentrification in San Francisco's Mission District: Indicators and Policy Recommendations" (PDF). Chapter 3: An Overview of the Mission District; History. Mission Economic Development Association. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 12, 2006. Retrieved November 27, 2006.

- ^ Nolte, Carl (January 29, 2004). "Centuries-old murals revealed in Mission Dolores Indians' hidden paintings open window into S.F.'s sacred past". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A-1. Retrieved November 27, 2006.

- ^ a b Via magazine, April 2003. Viamagazine.com (July 23, 2010).

- ^ "The Willows & 18th St. Ravine in 3D and 1860s Mission Amusements". Burrito Justice. March 10, 2011.

- ^ Craig, Christopher. "Woodward's Gardens". Encyclopedia of San Francisco. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013.

- ^ "The Mission Has Always Been The Home of Baseball", Burrito Justice, February 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c Graves, Donna J.; Watson, Shayne E. (October 2015). "LGBTQ Historic Context Statement". City and County of San Francisco Planning Department. pp. 10, 173. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ Svanevik, Michael; Burgett, Shirley (December 6, 2017). "Matters Historical: A bit of old Japan in a Colma cemetery". The Mercury News. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ The golden legacy of San Francisco's little hydrant that could Laura French, May 31, 2021, FireRescue1

- ^ a b Wells, Madeline (October 14, 2021). "'Sworn to secrecy': Ex-employees say The Chapel's ghost was real". SFGATE. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "LOS SIETE DE LA RAZA - FoundSF". www.foundsf.org. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Heins, Marjorie (March 1971). "Ramparts- Los Siete de la Raza" (PDF).

- ^ Carlsson, Chris (2020). Hidden San Francisco: A Guide to Lost Landscapes, Unsung Heroes and Radical Histories. Pluto Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvx077t5. ISBN 978-0-7453-4094-4. JSTOR j.ctvx077t5.

- ^ "Map of Lesbian Valencia Street". Researchgate. Gay Lesbian Bisexual Historical Society. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ "Valencia Street As A Lesbian Corridor: Living Memories". Shaping San Francisco. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ Brahinsky, Rachel (October 6, 2020). A People's Guide to the San Francisco Bay Area. University of California Press. p. 160. ISBN 9780520288379.

- ^ Bauer, Michael (April 30, 1995). "Arty Cafe Turns Into a Tapas Bar - Remodeled Picaro in the Mission District". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

Fifteen years ago Matilde Gomez was 25 and wanted a place to hang out in around the Roxie theater in the Mission District, so she opened Cafe Picaro right across the street. With few cafes in the area, it became the gathering place for the new bohemia, a collection of artists, poets and people on the political fringes.

- ^ Roberts, Chris (December 18, 2011). "Iconic Mission district transforming into a true melting pot". SF Examiner. Archived from the original on August 14, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

These commingling cultural contrasts are at least part of what makes the Mission one of The City's most popular and fascinating places.

- ^ "Upscale culture and gang violence share a small space". Los Angeles Times. (September 21, 2011).

- ^ "36 Hours in San Francisco", New York Times, September 14, 2008

- ^ Bowe, Rebecca (October 28, 2015). "SF Study Documents Sharp Decline in Mission's Latino Population". KQED.

- ^ [1] Archived February 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine sfgate.com

- ^ a b "SF Rec and Park Opens New Park On Site of Former A Parking Lot". San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department. June 23, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ Bittman, Mark. (May 11, 2010) "In the Mission District, a Great Cheap Lunch". The New York Times, May 11, 2010.

- ^ Woo, Stu (November 9, 2011). "Mission Munchers Bite 'Danger Dogs'". The Wall Street Journal. New York: Dow Jones. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ^ The 15 Coolest Neighborhoods in the World in 2016, How I Travel, retrieved November 15, 2016

- ^ Bittman, Mark (May 29, 2011). "San Francisco's New Pop-Up Restaurant". New York Times

- ^ Bittman, Mark. (December 9, 2001) "CHOICE TABLES; The Mission District: Affordable and Fun". New York Times, December 9, 2001.

- ^ "San Francisco's La Mejor Bakery Becomes Legacy Business". The San Francisco Standard. June 28, 2023. Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- ^ "'16th & Mission' gatherings offer raw performances and rowdy audiences – Bay Voices". Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ^ Hirsch, Daniel (December 19, 2014). "Dance Mission Faces Rent Hike, Uncertain Future (updated)". Mission Local. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ Latorre, Guisela (2008). Walls of empowerment: Chicana/o indigenist murals of California. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-0-292-71906-4.

- ^ "The Annotated "Mission in the Rain"". artsites.ucsc.edu. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- ^ CD Universe, "Santana S.F. Mission District Live '69 CD". Cduniverse.com (February 10, 2008).

- ^ KQED, "The Mission". Kqed.org.

- ^ David Dodd, The Annotated "Mission in the Rain". Arts.ucsc.edu.

- ^ Community Music Center San Francisco: Mission District Branch Archived March 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Sfcmc.org.

- ^ "Peter and Benjamin Bratt are on a mission". Los Angeles Times. April 10, 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ Mezynski, Neila. "Carlos Loarca: Spirit Dogs, Painting the Past into the Present". artdaily.org. Royalville Communications, Inc. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ "Carlos Loarca". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ Rodriguez, Abraham (November 12, 2019). "Sirron Norris exhibit to open on Saturday — his first in seven years". Mission Local. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ Whiting, Sam (January 15, 2015). "Dan Plasma's mission: Replace drugs with art on Mission alleyways". SFGATE. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ Fagan, Kevin (November 29, 2012). "Spain Rodriguez: Zap Comix artist dies". SFGATE. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ The Art of Michael Rios. Mvrios.com.

- ^ Weigert, Lili (June 10, 2007). "WORKING AT HOME / ARTISTS FIND AFFORDABLE LOFT SPACE IS SCARCE". SF Gate. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ "Xavier Viramontes". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ Documentary, A Life in Print: Xavier Viramontes Printmaker. Alifeinprint.net.

- ^ "ArtScene". Scott Williams. ArtScene. October 15 – November 12, 2005.

- ^ Flores, Jessica (October 7, 2021). "Outdoor theater makes Mission District heroes, history real in the actual streets". Datebook | San Francisco Arts & Entertainment Guide. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "10 Rising Stars of Art Explosion Open Studios". SF Station | San Francisco's City Guide. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "Project Artaud: An Artists' Village in San Francisco". Potrero View. April 6, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "The Return of San Francisco's The LAB, a Historic Experimental Art Space". KQED. July 22, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ San Francisco Carnaval. Carnaval.com.

- ^ Mission Local Archived September 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Mission Local (July 15, 2011).

- ^ Cesar E. Chavez Holiday Parade & Festival 2012. Cesarchavezday.org.

- ^ Transmarch.org. Transmarch.org.

- ^ The Dyke March.org. The Dyke March.org.

- ^ Sunday Streets SF. Thedykemarch.org.

- ^ Day of Dead SF. Day of Dead SF.

- ^ Dicum, Gregory (November 20, 2005). "San Francisco's Mission District: Eclectic, Eccentric, Electric". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2024. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ First Friday, SFFunCheap. Sf.funcheap.com (July 6, 2012).

- ^ ArtSpan. ArtSpan.

- ^ SF Fun Cheap. SF Fun Cheap (April 8, 2012).

- ^ "Photos: The 2014 'Hunky Jesus' Contest Bares Holy Man Flesh". SFist. Archived from the original on November 5, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Rock Make. Rock Make.

- ^ LitCrawl. LitCrawl (June 9, 2011).

- ^ Palmer, Tamara (September 26, 2012). "SF Weekly". Food for a Cause: This Weekend: Party on Block 18 Supports Mission Community, Plus There's a Pie Contest. SF Weekly, LP. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ^ Party on Block 18 San Francisco. Yelp.

- ^ SF Station. SF Station (October 25, 2008).

- ^ Guardians of the City. Guardiansofthecity.org.

- ^ "About". El Tecolote.

- ^ "About". Mission Local.

- ^ "About". El Reportero.

- ^ a b "16th & Mission". Critical Sustainabilities. February 9, 2015.

- ^ "San Francisco's Mission District: The Controversial Gentrification". Smart Cities Dive.

- ^ "Eastern Neighborhoods Plans". SF Planning.

- ^ "John O'Connell High School". San Francisco Unified School District. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8 Community School". San Francisco Unified School District. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "Bryant Elementary School". San Francisco Unified School District. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "César Chávez Elementary School". San Francisco Unified School District. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "Leonard R. Flynn Elementary School". San Francisco Unified School District. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "Marshall Elementary School". San Francisco Unified School District. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "George R. Moscone Elementary School". San Francisco Unified School District. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "Zaida T. Rodriguez Early Education School". San Francisco Unified School District. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "Hilltop School". San Francisco Unified School District. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ Nolte, Carl (May 17, 2014). "St. Peter's Catholic School has changed with the Mission". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved May 30, 2020. - Alternate link at the Houston Chronicle

External links

[edit]- The Mission – Neighborhoods: The Hidden Cities of San Francisco (KQED, 1994)

- Mission Dolores Neighborhood Association

- North Mission Neighborhood Association

- San Francisco Chronicle, November 26, 1995: 'Neo-Hipsters Keep the Beat in the Mission'

- New York Times, September 14, 2008: '36 Hours in San Francisco's Mission District'

- New York Times, November 20, 2005: 'San Francisco's Mission District: Eclectic, Eccentric, Electric'

- New York Times, November 5, 2000: "Mission District Fights Dot-Com Fever'

- New York Times, January 16, 1999: 'In Old Mission District: Changing Grit to Gold'

- What Its Like To Get Kicked Out of Your Neighborhood