Palomar Observatory

| |

| Alternative names | 675 PA |

|---|---|

| Organization | |

| Observatory code | 675 |

| Location | San Diego County, California |

| Coordinates | 33°21′23″N 116°51′54″W / 33.3564°N 116.865°W |

| Altitude | 1,712 m (5,617 ft) |

| Established | 1928 |

| Website | www |

| Telescopes |

|

| | |

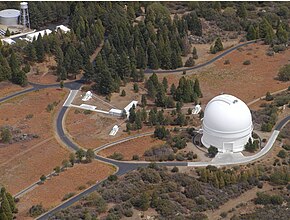

Palomar Observatory is an astronomical research observatory in the Palomar Mountains of San Diego County, California, United States. It is owned and operated by the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Research time at the observatory is granted to Caltech and its research partners, which include the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Yale University,[1] and the National Astronomical Observatories of China.[2]

The observatory operates several telescopes, including the 200-inch (5.1 m) Hale Telescope,[3] the 48-inch (1.2 m) Samuel Oschin telescope[4] (dedicated to the Zwicky Transient Facility, ZTF),[5] the Palomar 60-inch (1.5 m) Telescope,[6] and the 30-centimetre (12-inch) Gattini-IR telescope.[7] Decommissioned instruments include the Palomar Testbed Interferometer and the first telescopes at the observatory, an 18-inch (46 cm) Schmidt camera from 1936.

History

[edit]

Hale's vision for large telescopes and Palomar Observatory

[edit]Astronomer George Ellery Hale, whose vision created Palomar Observatory, built the world's largest telescope four times in succession.[8] He published a 1928 article proposing what was to become the 200-inch Palomar reflector; it was an invitation to the American public to learn about how large telescopes could help answer questions relating to the fundamental nature of the universe. Hale followed this article with a letter to the International Education Board (later absorbed into the General Education Board) of the Rockefeller Foundation dated April 16, 1928, in which he requested funding for this project. In his letter, Hale stated:

"No method of advancing science is so productive as the development of new and more powerful instruments and methods of research. A larger telescope would not only furnish the necessary gain in light space-penetration and photographic resolving power, but permit the application of ideas and devices derived chiefly from the recent fundamental advances in physics and chemistry."

Hale Telescope

[edit]The 200-inch telescope is named after astronomer and telescope builder George Ellery Hale. It was built by Caltech with a $6 million grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, using a Pyrex blank manufactured by Corning Glass Works under the direction of George McCauley. Dr. J.A. Anderson was the initial project manager, assigned in the early 1930s.[9] The telescope (the largest in the world at that time) saw first light January 26, 1949, targeting NGC 2261.[10] The American astronomer Edwin Powell Hubble was the first astronomer to use the telescope.

The 200-inch telescope was the largest telescope in the world from 1949 until 1975, when the Russian BTA-6 telescope saw first light. Astronomers using the Hale Telescope have discovered quasars (a subset of what was to become known as Active Galactic Nuclei) at cosmological distances. They have studied the chemistry of stellar populations, leading to an understanding of the stellar nucleosynthesis as to origin of elements in the universe in their observed abundances, and have discovered thousands of asteroids. A one-tenth-scale engineering model of the telescope at Corning Community College in Corning, New York, home of the Corning Glass Works (now Corning Incorporated), was used to discover at least one minor planet, 34419 Corning.†

Architecture and design

[edit]

Russell W. Porter developed the Art Deco architecture of the Observatory's buildings, including the dome of the 200-inch Hale Telescope. Porter was also responsible for much of the technical design of the Hale Telescope and Schmidt Cameras, producing a series of cross-section engineering drawings. Porter worked on the designs in collaboration with many engineers and Caltech committee members.[11][12][13]

Max Mason directed the construction and Theodore von Karman was involved in the engineering.

Directors

[edit]- Ira Sprague Bowen, 1948–1964

- Horace Welcome Babcock, 1964–1978

- Maarten Schmidt, 1978–1980

- Gerry Neugebauer, 1980–1994

- James Westphal, 1994–1997

- Wallace Leslie William Sargent, 1997–2000

- Richard Ellis, 2000–2006

- Shrinivas Kulkarni, 2006–2018

- Jonas Zmuidzinas, 2018–

Palomar Observatory and light pollution

[edit]Much of the surrounding region of Southern California has adopted shielded lighting to reduce the light pollution that would potentially affect the observatory.[14]

Telescopes and instruments

[edit]

- The 200-inch (5.1 m) Hale Telescope was first proposed in 1928 and has been operational since 1949. It was the largest telescope in the world for 26 years.[3][citation needed]

- A 60-inch (1.5 m) reflecting telescope is located in the Oscar Mayer Building, and operates fully robotically. The telescope became operational in 1970, and was built to increase sky access for Palomar astronomers. Among its notable accomplishments is the discovery of the first brown dwarf.[6] The 60-inch telescope currently[when?] hosts the SED Machine integral field spectrograph instrument used as part of ZTF transient followup and classification.[15][16]

- The 48-inch (1.2 m) Samuel Oschin telescope development began in 1938, and the telescope saw first light in 1948. It was initially called the 48-inch Schmidt, and was dedicated to Samuel Oschin in 1986.[4] Among many notable accomplishments, Oschin observations led to the discovery of the important dwarf planets Eris and Sedna.[17] Eris's discovery initiated discussions in the international astronomy community that led to Pluto being re-classified as a dwarf planet in 2006. The Oschin presently operates fully robotically and hosts the 570-million-pixel ZTF Camera [18]—the discovery engine for the ZTF project.

- The 40-inch (1.0 m) WINTER (The Wide-field Infrared Transient Explorer) 1x1-degree reflecting robotic telescope has been operational since 2021. It is dedicated to the seeing-limited time domain survey of the infrared (IR) sky, with a particular emphasis on identifying r-process material in binary neutron star (BNS) merger remnants detected by LIGO. The instrument observes in Y, J, and a short-H (Hs) band tuned to the long-wave cutoff of the InGaAs sensors, covering a wavelength range from 0.9 to 1.7 microns.[19]

Decommissioned instruments

[edit]- An 18-inch (46 cm) Schmidt camera became the first operational telescope at the Palomar in 1936. In the 1930s, Fritz Zwicky and Walter Baade advocated adding survey telescopes at Palomar, and the 18-inch was developed to demonstrate the Schmidt concept. Zwicky used the 18-inch to discover over 100 supernovae in other galaxies. Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 was discovered with this instrument in 1993. It has since been decommissioned and is on display at the small museum/visitor center.[20][21]

- The Palomar Testbed Interferometer (PTI) was a multi-telescope instrument that made high-angular-resolution measurements of the apparent sizes and relative positions of stars. The apparent sizes and in some cases shapes of bright stars were measured with PTI, as well as the apparent orbits of multiple stellar systems. PTI operated from 1995 to 2008.[22]

- The Palomar Planet Search Telescope (PPST), also known as Sleuth, was a 10-centimetre (3.9 in) robotic telescope that operated from 2003 until 2008. It was dedicated to the search for planets around other stars using the transit method. It operated in conjunction with telescopes at Lowell Observatory and in the Canary Islands as part of the Trans-Atlantic Exoplanet Survey (TrES).[23]

Research

[edit]

Palomar Observatory remains an active research facility, operating multiple telescopes every clear night, and supporting a large international community of astronomers who study a broad range of research topics.

The Hale Telescope[3] remains in active research use and operates with a diverse instrument suite of optical and near-infrared spectrometers and imaging cameras at multiple foci. The Hale also operates with a multi-stage, high-order adaptive optics system to provide diffraction-limited imaging in the near-infrared. Key historical science results with the Hale include cosmological measurement of the Hubble flow, the discovery of quasars as the precursor of Active Galactic Nuclei, and studies of stellar populations and stellar nucleosynthesis.

The Oschin and 60-inch telescopes operate robotically and together support a major transient astronomy program, the Zwicky Transient Facility.

The Oschin was created to facilitate astronomical reconnaissance, and has been used in many notable astronomical surveys—among them are:

POSS-I

[edit]The initial Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS or POSS-I), sponsored by the National Geographic Institute, was completed in 1958. The first plates were exposed in November 1948 and the last in April 1958. This survey was performed using 14-inch2 (6-degree2) blue-sensitive (Kodak 103a-O) and red-sensitive (Kodak 103a-E) photographic plates on the Oschin Telescope. The survey covered the sky from a declination of +90° (celestial north pole) to −27° and all right ascensions and had a sensitivity to +22 magnitudes (about 1 million times fainter than the limit of human vision). A southern extension extending the sky coverage of the POSS to −33° declination was shot in 1957–1958. The final POSS I dataset consisted of 937 plate pairs.

The Digitized Sky Survey (DSS) produced images which were based on the photographic data developed in the course of POSS-I.[24]

J.B. Whiteoak, an Australian radio astronomer, used the same instrument to extend POSS-I data south to −42° declination. Whiteoak's observations used using the same field centers as the corresponding northern declination zones. Unlike POSS-I, the Whiteoak extension consisted only of red-sensitive (Kodak 103a-E) photographic plates.

POSS-II

[edit]The Second Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS II, sometimes Second Palomar Sky Survey) was performed in the 1980s and 1990s and made use of better, faster films and an upgraded telescope. The Oschin Schmidt was upgraded with an achromatic corrector and provisions for autoguiding. Images were recorded in three wavelengths: blue (IIIaJ. 480 nm), red (IIIaF, 650 nm), and near-infrared (IVN, 850 nm) plates. Observers on POSS II included C. Brewer, D. Griffiths, W. McKinley, J. Dave Mendenhall, K. Rykoski, Jeffrey L. Phinney, and Jean Mueller (who discovered over 100 supernovae by comparing the POSS I and POSS II plates). Mueller also discovered several comets and minor planets during the course of POSS II, and the bright Comet Wilson 1986 was discovered by then-graduate-student C. Wilson early in the survey.[25]

Until the completion of the Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS), POSS II was the most extensive wide-field sky survey. When completed, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey will surpass POSS I and POSS II in depth, although the POSS covers almost 2.5 times more area on the sky.

POSS II also exists in digitized form (that is, the photographic plates were scanned) as part of the Digitized Sky Survey (DSS).[26]

QUEST

[edit]The multi-year POSS projects were followed by the Palomar Quasar Equatorial Survey Team (QUEST) Variability survey.[27] This survey yielded results that were used by several projects, including the Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking project. Another program that used the QUEST results discovered 90377 Sedna on 14 November 2003, and around 40 Kuiper belt objects. Other programs that share the camera are Shri Kulkarni's search for gamma-ray bursts (this takes advantage of the automated telescope's ability to react as soon as a burst is seen and take a series of snapshots of the fading burst), Richard Ellis's search for supernovae to test whether the universe's expansion is accelerating or not, and S. George Djorgovski's quasar search.

The camera for the Palomar QUEST Survey was a mosaic of 112 charge-coupled devices (CCDs) covering the whole (4° × 4°) field of view of the Schmidt telescope. At the time it was built, it was the largest CCD mosaic used in an astronomical camera. This instrument was used to produce The Big Picture, the largest astronomical photograph ever produced.[28] The Big Picture is on display at Griffith Observatory.

Current research

[edit]Current research programs on the 200-inch Hale Telescope cover the range of the observable universe, including studies on near-Earth asteroids, outer Solar System planets, Kuiper Belt objects, star formation, exoplanets,[29] black holes and x-ray binaries, supernovae and other transient source followup, and quasars/Active Galactic Nuclei.[30]

The 48-inch Samuel Oschin Schmidt Telescope operates robotically, and supports a new transient astronomy sky survey, the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF).[5]

The 60-inch telescope operates robotically, and supports ZTF by providing rapid, low-dispersion optical spectra for initial transient classification using the for-purpose Spectral Energy Distribution Machine (SEDM)[31] integral field spectrograph.

Visiting and public engagement

[edit]

Palomar Observatory is an active research facility. However, selected observatory areas are open to the public during the day. Visitors can take self-guided tours of the 200-inch telescope daily from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. The observatory is open 7 days a week, year round, except for December 24 and 25 and during times of inclement weather. Guided tours of the 200-inch Hale Telescope dome and observing area are available Saturdays and Sundays from April through October. Behind-the-scenes tours for the public are offered through the community support group, Palomar Observatory Docents.[32]

Palomar Observatory also has an on-site museum—the Greenway Visitor Center,[21] containing observatory and astronomy-relevant exhibits, a gift shop,[33] and hosts periodic public events.[34]

For those unable to travel to the observatory, Palomar provides an extensive virtual tour that provides virtual access to all the major research telescopes on-site and the Greenway Center and has extensive embedded multimedia to provide additional context.[35] Similarly the observatory actively maintains an extensive website[36] and YouTube channel[37] to support public engagement.

The observatory is located off State Route 76 in northern San Diego County, California, two hours' drive from downtown San Diego and three hours' drive from central Los Angeles (UCLA, LAX airport).[38] Those staying at the nearby Palomar Campground can visit Palomar Observatory by hiking 2.2 miles (3.5 km) up Observatory Trail.[39]

Climate

[edit]Palomar has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa).

| Climate data for Palomar Observatory (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1938–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 82 (28) |

77 (25) |

82 (28) |

83 (28) |

91 (33) |

104 (40) |

100 (38) |

100 (38) |

100 (38) |

97 (36) |

80 (27) |

80 (27) |

104 (40) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 63.4 (17.4) |

63.9 (17.7) |

69.5 (20.8) |

76.1 (24.5) |

82.0 (27.8) |

88.7 (31.5) |

92.9 (33.8) |

92.0 (33.3) |

88.3 (31.3) |

81.0 (27.2) |

71.5 (21.9) |

64.8 (18.2) |

94.3 (34.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 51.4 (10.8) |

51.0 (10.6) |

56.0 (13.3) |

61.3 (16.3) |

69.3 (20.7) |

78.5 (25.8) |

84.3 (29.1) |

84.4 (29.1) |

79.3 (26.3) |

69.1 (20.6) |

58.2 (14.6) |

50.7 (10.4) |

66.1 (18.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 37.1 (2.8) |

36.1 (2.3) |

38.7 (3.7) |

41.8 (5.4) |

48.4 (9.1) |

57.0 (13.9) |

63.9 (17.7) |

64.5 (18.1) |

59.5 (15.3) |

50.8 (10.4) |

42.5 (5.8) |

36.6 (2.6) |

48.1 (8.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 24.4 (−4.2) |

24.0 (−4.4) |

25.4 (−3.7) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

33.4 (0.8) |

41.2 (5.1) |

55.3 (12.9) |

55.1 (12.8) |

45.5 (7.5) |

36.8 (2.7) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

23.9 (−4.5) |

19.8 (−6.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 8 (−13) |

12 (−11) |

16 (−9) |

19 (−7) |

24 (−4) |

28 (−2) |

36 (2) |

36 (2) |

30 (−1) |

18 (−8) |

17 (−8) |

8 (−13) |

8 (−13) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.93 (151) |

7.34 (186) |

4.61 (117) |

2.00 (51) |

0.89 (23) |

0.17 (4.3) |

0.29 (7.4) |

0.68 (17) |

0.48 (12) |

1.21 (31) |

2.25 (57) |

4.56 (116) |

30.41 (772) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.2 (16) |

10.6 (27) |

3.1 (7.9) |

3.5 (8.9) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

2.4 (6.1) |

26.2 (67) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.5 | 7.3 | 5.9 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 5.8 | 41 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.2 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 7.1 |

| Source: NOAA[40] | |||||||||||||

Selected books

[edit]- 1983 — Calvino, Italo. Mr. Palomar. Torino: G. Einaudi. ISBN 9788806056797; OCLC 461880054 (in Italian)

- 1987 — Preston, Richard. First Light. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 9780871132000; OCLC 16004290

- 1994 — Florence, Ronald. The Perfect Machine. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 9780060182052; OCLC 611549937

- 2010 — Brown, Michael E. How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming. Spiegel & Grau. ISBN 0-385-53108-7; OCLC 495271396

- 2020 — Schweizer, Linda. Cosmic Odyssey. MIT Press ISBN 978-0-262-04429-5

See also

[edit]- List of astronomical observatories

- Mount Laguna Observatory

- National Geographic Society – Palomar Observatory Sky Survey

References

[edit]- ^ Yale University, Dept. of Astronomy Archived 2021-09-02 at the Wayback Machine: Facilities

- ^ "National Astronomical Observatories". english.nao.cas.cn.

- ^ a b c "Caltech Astronomy – The 200-inch Hale Telescope". Caltech Astronomy. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- ^ a b "Caltech Astronomy – Samuel Oschin Telescope". Caltech Astronomy. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- ^ a b "Zwicky Transient Facility Website". ztf.caltech.edu.)

- ^ a b "Caltech Astronomy – The 60-inch Telescope". Caltech Astronomy. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- ^ "Gattini IR". sites.astro.caltech.edu.

- ^ "George Ellery Hale | American astronomer". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

- ^ Hearst Magazines (April 1942). "Super Camera of the Skies". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. p. 52.

- ^ "60th Anniversary of Hale Telescope," 365 Days of Astronomy (podcast). January 26, 2009.

- ^ June 2014, Elizabeth Howell 20 (20 June 2014). "Palomar Observatory: Facts & Discoveries". Space.com. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Palomar Observatory | observatory, California, United States". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- ^ "Palomar, After 50 Years". San Diego History Center | San Diego, CA | Our City, Our Story. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- ^ International Dark-Sky Association Archived 2008-01-01 at the Wayback Machine (IDA): "Sky Glow Effect on Existing Large Telescopes" Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine, IDA Info #20.

- ^ "Welcome to SED Machine's documentation!". sites.astro.caltech.edu. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- ^ Blagorodnova, Nadejda (March 2018). "The SED Machine: A Robotic Spectrograph for Fast Transient Classification". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 130 (985): 035003. arXiv:1710.02917. Bibcode:2018PASP..130c5003B. doi:10.1088/1538-3873/aaa53f. S2CID 54892690.

- ^ "Caltech Astronomy – Discoveries from Palomar Observatory's 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope". Caltech Astronomy. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- ^ Dekany, Richard; Smith, Roger M.; Belicki, Justin; Delacroix, Alexandre; Duggan, Gina; Feeney, Michael; Hale, David; Kaye, Stephen; Milburn, Jennifer; Murphy, Patrick; Porter, Michael; Reiley, Dan; Riddle, Reed; Rodriguez, Hector; Bellm, Eric (2016). "The Zwicky Transient Facility Camera" (PDF). In Evans, Christopher J.; Simard, Luc; Takami, Hideki (eds.). Ground-based and Airborne Instrumentation for Astronomy VI. Vol. 9908. pp. 99085M. Bibcode:2016SPIE.9908E..5MD. doi:10.1117/12.2234558. S2CID 38035871.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Frostig, Danielle; Baker, John W.; Brown, Joshua; Burruss, Rick; Clark, Kristin; Fżrész, Gábor; Ganciu, Nicolae; Hinrichsen, Erik; Karambelkar, Viraj R.; Kasliwal, Mansi M.; Lourie, Nathan P.; Malonis, Andrew; Simcoe, Robert A.; Zolkower, Jeffry (2020). "Design requirements for the Wide-field Infrared Transient Explorer (WINTER)". In Evans, Christopher J; Bryant, Julia J; Motohara, Kentaro (eds.). Ground-based and Airborne Instrumentation for Astronomy VIII. Vol. 11447. p. 113. arXiv:2105.01219. Bibcode:2020SPIE11447E..67F. doi:10.1117/12.2562842. hdl:1721.1/142211. ISBN 9781510636811. S2CID 230542025. Retrieved 2021-10-18.

- ^ "Caltech Astronomy – The 18-inch Schmidt Telescope". Caltech Astronomy. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- ^ a b "Greenway Visitor Center". sites.astro.caltech.edu.

- ^ "Caltech Astronomy – Palomar Testbed Interferometer (PTI)". Caltech Astronomy. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- ^ "Caltech Astronomy – Sleuth: The Palomar Planet Finder". Palomar Skies. 30 October 2009. Retrieved 2014-12-09.

- ^ Minnesota Automated Plate Scanner (MAPS): MAPS catalogue; Mollise, Rod. (2006). The Urban Astronomer's Guide: a Walking tour of the Cosmos for City Sky Watchers , p. 238, at Google Books

- ^ Caltech: The Second Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS II) Archived 2009-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NASA/Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI).: Multimission Archive at STScI (MAST)

- ^ Caltech press release: "New Sky Survey Begins at Palomar Observatory." Archived 2004-04-05 at the Wayback Machine July 29, 2003.

- ^ Caltech: "The Big Picture" Archived 2007-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ JPL: "Planet-Hunting Method Succeeds at Last." Archived 2022-02-01 at the Wayback Machine May 28, 2009.

- ^ Caltech: Hale Telescope Observing Runs Archived 2012-12-12 at archive.today

- ^ Blagorodnova, Nadejda; Neill, James D.; Walters, Richard; Kulkarni, Shrinivas R.; Fremling, Christoffer; Ben-Ami, Sagi; Dekany, Richard G.; Fucik, Jason R.; Konidaris, Nick; Nash, Reston; Ngeow, Chow-Choong; Ofek, Eran O.; Sullivan, Donal O'; Quimby, Robert; Ritter, Andreas; Vyhmeister, Karl E. (2018). "The SED Machine: A Robotic Spectrograph for Fast Transient Classification". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 130 (985): 035003. arXiv:1710.02917. Bibcode:2018PASP..130c5003B. doi:10.1088/1538-3873/aaa53f. S2CID 54892690.

- ^ "Docents". sites.astro.caltech.edu.

- ^ "Palomar Observatory Gift and Book Store". store.palomar.caltech.edu.

- ^ "Greenway Talk Series". sites.astro.caltech.edu.

- ^ "Virtual Tour". sites.astro.caltech.edu.

- ^ "Welcome to Palomar Observatory". sites.astro.caltech.edu.

- ^ "Palomar Observatory – YouTube". YouTube.

- ^ "Driving Directions to Palomar Observatory". sites.astro.caltech.edu.

- ^ "Observatory Trail in Cleveland National Forest". hikespeak.com. Hikespeak. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- ^ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Crawford, David Livingston (1966). The Construction of large telescopes. London & New York: Academic Press. OCLC 1093049.

- Mollise, Rod (2006). The Urban Astronomer's Guide: a Walking Tour of the Cosmos for City Sky Watchers. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-1846282171. OCLC 299995003.

- Watterson, T.V. (1941). Palomar Observatory. San Diego, California: Frye & Smith. OCLC 6327013.

External links

[edit]- Caltech Astronomy: Palomar Observatory – official observatory website

- Palomar Skies, news and history written by former Palomar public affairs coordinator Scott Kardel

- The SBO Palomar Sky Survey Prints

- Palomar Observatory Clear Sky Clock Forecast of observing conditions.

- Palomar Observatory YouTube Channel

- Palomar Observatory Virtual Tour