Signs and symptoms of multiple sclerosis

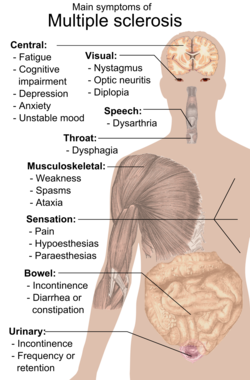

The signs and symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS) encompass a wide range of neurological and physical manifestations, including vision problems, muscle weakness, coordination difficulties, and cognitive impairment, varying significantly in severity and progression among individuals.

Multiple sclerosis can cause a variety of symptoms: changes in sensation (hypoesthesia), muscle weakness, abnormal muscle spasms, or difficulty moving; difficulties with coordination and balance; problems in speech (dysarthria) or swallowing (dysphagia), visual problems (nystagmus, optic neuritis, phosphenes or diplopia), fatigue and acute or chronic pain syndromes, bladder and bowel difficulties, cognitive impairment, or emotional symptomatology (mainly major depression). The main clinical measure in progression of the disability and severity of the symptoms is the Expanded Disability Status Scale or EDSS.[1]

The initial attacks are often transient, mild (or asymptomatic), and self-limited. They often do not prompt a health care visit and sometimes are only identified in retrospect once the diagnosis has been made after further attacks. The most common initial symptoms reported are: changes in sensation in the arms, legs or face (33%), complete or partial vision loss (optic neuritis) (20%), weakness (13%), double vision (7%), unsteadiness when walking (5%), and balance problems (3%); but many rare initial symptoms have been reported such as aphasia or psychosis.[2][3] Fifteen percent of individuals have multiple symptoms when they first seek medical attention.[4]

Fatigue[edit]

Fatigue is very common[5] and disabling in MS.[6][7][8] Some 65% of people with MS experience fatigue symptomatology, and of these some 15-40% report fatigue as their most disabling MS symptom.[9] A 2023 study found that effect on fatigue was the most valued attribute of MS therapy, and that participants would accept six additional relapses in 2 years and a decrease of 7 years in time to disease progression to improve either cognitive or physical fatigue from "quite a bit of difficulty" to "no difficulty."[10]

The pathophysiology and mechanisms causing MS fatigue are not well understood.[11][12][13][14][excessive citations]

MS fatigue can be effected by body heat[15][16] and this may differentiate MS fatigue from other primary fatigue.[5][17][18][19][20][21][15][excessive citations]

Perceived fatigue and fatigability (loss of strength) are regarded independently.[22][23] Primary MS fatigue is sometimes called "lassitude.'[24] MS fatigue may reduce during periods of other MS symptom remission.[25][26]

Primary vs. secondary[edit]

In some areas it has been proposed that fatigue be separated into primary fatigue, caused directly by a disease process, and secondary fatigue, caused by more general impacts on the person of having a disease (such as disrupted sleep).[27][28][29][30][excessive citations]

Contributory factors to secondary fatigue[edit]

Factors such as disturbed sleep, chronic pain, poor nutrition, or even some medications can all contribute to secondary fatigue and medical professionals are encouraged to identify and modify them.[31]

Association with depression[edit]

Early 2000s commentary saw a close relationship of secondary fatigue with depressive symptomatology.[32] When depression is reduced fatigue also tends to reduce and it is recommended that patients should be evaluated for depression before other therapeutic approaches are used.[33]

Correlation with brain changes[edit]

Studies have found MS fatigue correlates, not with lesion volume or brain atrophy, but with damage to NAWM (normal appearing white matter) (which will not show on normal MRI but will show on DTI (diffusion tensor imaging)).[34][35][36][37][38][39] The correlation becomes unreliable due to ageing in patients aged over 65.[40]

A 2008 study found MS fatigue correlated with lesion load and brain atrophy.[41]

Medications[edit]

Medications used to treat MS fatigue include amantadine,[42][43] pemoline,[44][45] methylphenidate, and modafinil,[46] as well as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and psychological interventions of energy conservation;[47][48] but their effects are limited.[46] For these reasons fatigue is a difficult symptom to manage.

Technology[edit]

Apps are being experimented with in the field of MS fatigue.[49]

Bladder and bowel[edit]

Bladder problems (See also urinary system and urination) appear in 70–80% of people with multiple sclerosis (MS) and they have an important effect both on hygiene habits and social activity.[50][51] Bladder problems are usually related with high levels of disability and pyramidal signs in lower limbs.[52]

The most common problems are an increase in frequency and urgency (incontinence) but difficulties to begin urination, hesitation, leaking, sensation of incomplete urination, and retention also appear. When retention occurs secondary urinary infections are common.

There are many cortical and subcortical structures implicated in urination[53] and MS lesions in various central nervous system structures can cause these kinds of symptoms.

Treatment objectives are the alleviation of symptoms of urinary dysfunction, treatment of urinary infections, reduction of complicating factors and the preservation of renal function. Treatments can be classified in two main subtypes: pharmacological and non-pharmacological. Pharmacological treatments vary greatly depending on the origin or type of dysfunction and some examples of the medications used are:[54] alfuzosin for retention,[55] trospium and flavoxate for urgency and incontinency,[56][57] and desmopressin for nocturia.[58][59] Non pharmacological treatments involve the use of pelvic floor muscle training, stimulation, biofeedback, pessaries, bladder retraining, and sometimes intermittent catheterization.[60][61]

Bowel problems affect around 70% of patients. Around 50% of patients experience constipation and up to 30% experience fecal incontinence.[61] Cause of bowel impairments in MS patients is usually either a reduced gut motility or an impairment in neurological control of defecation. The former is commonly related to immobility or secondary effects from drugs used in the treatment of the disease.[61] Pain or problems with defecation can be helped with a diet change which includes among other changes an increased fluid intake, oral laxatives or suppositories and enemas when habit changes and oral measures are not enough to control the problems.[61][62]

Cognitive[edit]

Some of the most common deficits affect recent memory, attention, processing speed, visual-spatial abilities and executive function.[63][64] Symptoms related to cognition include emotional instability and fatigue including neurological fatigue. Commonly a form of cognitive disarray is experienced, where specific cognitive processes may remain unaffected, but cognitive processes as a whole are impaired. Cognitive deficits are independent of physical disability and can occur in the absence of neurological dysfunction.[65] Severe impairment is a major predictor of a low quality of life, unemployment, caregiver distress,[66] and difficulty in driving;[67] limitations in a patient's social and work activities are also correlated with the extent of impairment.[65]

Cognitive impairments occur in about 40 to 60 percent of patients with multiple sclerosis,[68] with the lowest percentages usually from community-based studies and the highest ones from hospital-based. Impairments may be present at the beginning of the disease.[69] Probable multiple sclerosis patients, meaning after a first attack but before a secondary confirmatory one, have up to 50 percent of patients with impairment at onset.[70] Dementia is rare and occurs in only five percent of patients.[65]

Measures of tissue atrophy are well correlated with, and predict, cognitive dysfunction. Neuropsychological outcomes are highly correlated with linear measures of sub-cortical atrophy. Cognitive impairment is the result of not only tissue damage,[71] but tissue repair and adaptive functional reorganization.[66] Neuropsychological testing is important for determining the extent of cognitive deficits. Neuropsychological rehabilitation may help to reverse or decrease the cognitive deficits although studies on the issue have been of low quality.[72] Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are commonly used to treat Alzheimer's disease related dementia and so are thought to have potential in treating the cognitive deficits in multiple sclerosis. They have been found to be effective in preliminary clinical trials.[72]

Emotional[edit]

Emotional symptoms are also common and are thought to be both a normal response to having a debilitating disease and the result of damage to specific areas of the central nervous system that generate and control emotions.[citation needed]

Clinical depression is the most common neuropsychiatric condition: lifetime depression prevalence rates of 40–50% and 12-month prevalence rates around 20% have been typically reported for samples of people with MS; these figures are considerably higher than those for the general population or for people with other chronic illnesses.[73][74] Brain imaging studies trying to relate depression to lesions in certain regions of the brain have met with variable success. On balance the evidence seems to favour an association with neuropathology in the left anterior temporal/parietal regions.[75]

Other feelings such as anger, anxiety, frustration, and hopelessness also appear frequently. Suicide is a possibility, since it accounts for 15% of MS deaths.[76]

Rarely psychosis may also be featured.[77]

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia[edit]

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia is a disorder of conjugate lateral gaze. The affected eye shows impairment of adduction. The partner eye diverges from the affected eye during abduction, producing diplopia; during extreme abduction, compensatory nystagmus can be seen in the partner eye. Diplopia means double vision while nystagmus is involuntary eye movement characterized by alternating smooth pursuit in one direction and a saccadic movement in the other direction.[citation needed]

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia occurs when MS affects a part of the brain stem called the medial longitudinal fasciculus, which is responsible for communication between the two eyes by connecting the abducens nucleus of one side to the oculomotor nucleus of the opposite side. This results in the failure of the medial rectus muscle to contract appropriately, so that the eyes do not move equally (called disconjugate gaze).[citation needed]

Different drugs as well as optic compensatory systems and prisms can be used to improve these symptoms.[78][79][80][81] Surgery can also be used in some cases for this problem.[82]

Mobility restrictions[edit]

Restrictions in mobility (walking, transfers, bed mobility etc.) are common in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Although this is not something constant it can happen when experiencing a flare up. Within 10 years after the onset of MS one-third of patients reach a score of 6 on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), requiring the use of a unilateral walking aid, and by 30 years the proportion increases to 83%. Within five years of onset the EDSS is six in 50% of those with the progressive form of MS.[83]

A wide range of impairments may exist in people with MS, which can act either alone or in combination to impact directly on a person's balance, function and mobility. Such impairments include fatigue, weakness, hypertonicity, low exercise tolerance, impaired balance, ataxia and tremor.[84]

Interventions may be aimed at the individual impairments that reduce mobility or at the level of disability. This second level intervention includes provision, education, and instruction in the use of equipment such as walking aids, wheelchairs, motorized scooters and car adaptations as well as instruction on compensatory strategies to accomplish an activity — for example undertaking safe transfers by pivoting in a flexed posture rather than standing up and stepping around.

Optic neuritis[edit]

Up to 50% of patients with MS will develop an episode of optic neuritis and 20% of the time optic neuritis is the presenting sign of MS. The presence of demyelinating white matter lesions on brain MRIs at the time of presentation for optic neuritis is the strongest predictor in developing clinical diagnosis of MS. Almost half of patients with optic neuritis have white matter lesions consistent with multiple sclerosis.

At five year follow-ups the overall risk of developing MS is 30%, with or without MRI lesions. Patients with a normal MRI still develop MS (16%), but at a lower rate compared to those patients with three or more MRI lesions (51%). From the other perspective, however, 44% of patients with any demyelinating lesions on MRI at presentation will not have developed MS ten years later.[85][86]

Individuals experience rapid onset of pain in one eye followed by blurry vision in part or all its visual field. Flashes of light (phosphenes) may also be present.[87] Inflammation of the optic nerve causes loss of vision most usually by the swelling and destruction of the myelin sheath covering the optic nerve.

The blurred vision usually resolves within 10 weeks but individuals are often left with less vivid color vision, especially red, in the affected eye.[citation needed]

A systemic intravenous treatment with corticosteroids may quicken the healing of the optic nerve, prevent complete loss of vision and delay the onset of other symptoms.[citation needed]

Asymmetry in thickness of RNFL as indicator of optic neuritis in MS[edit]

Asymmetry between the eyes in thickness of RNFL has been proposed as a strong indicator of optic neuritis in MS.[88][89][90] RNFL data may indicate the pace of future development of the MS.[91][92]

Pain[edit]

Pain is a common symptom in MS. A recent study systematically pooling results from 28 studies (7101 patients) estimates that pain affects 63% of people with MS.[93] These 28 studies described pain in a large range of different people with MS. The authors found no evidence that pain was more common in people with progressive types of MS, in females compared to males, in people with different levels of disability, or in people who had had MS for different periods of time.

Pain can be severe and debilitating, and can have a profound effect on the quality of life and mental health of those affected.[94] Certain types of pain are thought to sometimes appear after a lesion to the ascending or descending tracts that control the transmission of painful stimulus, such as the anterolateral system, but many other causes are also possible.[80] The most prevalent types of pain are thought to be headaches (43%), dysesthetic limb pain (26%), back pain (20%), painful spasms (15%) such as the MS Hug,[95] painful Lhermitte's phenomenon (16%) and Trigeminal Neuralgia (3%).[93] These authors did not however find enough data to quantify the prevalence of painful optic neuritis.

Acute pain is mainly due to optic neuritis, trigeminal neuralgia, Lhermitte's sign or dysesthesias.[96] Subacute pain is usually secondary to the disease and can be a consequence of spending too much time in the same position, urinary retention, or infected skin ulcers. Chronic pain is common and harder to treat.[citation needed]

Trigeminal neuralgia[edit]

Trigeminal neuralgia (or "tic douloureux") is a disorder of the trigeminal nerve that causes episodes of intense pain in the eyes, lips, nose, scalp, forehead, and jaw, affecting 2-4% of MS patients.[93] The episodes of pain occur paroxysmally (suddenly) and the patients describe it as trigger area on the face, so sensitive that touching or even air currents can bring an episode of pain. Usually it is successfully treated with anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine,[97] or phenytoin[98] although others such as gabapentin[99] can be used.[100] When drugs are not effective, surgery may be recommended. Glycerol rhizotomy (surgical injection of glycerol into a nerve) has been studied[101] although the beneficial effects and risks in MS patients of the procedures that relieve pressure on the nerve are still under discussion.[102][103]

Lhermitte's sign[edit]

Lhermitte's sign is an electrical sensation that runs down the back and into the limbs and is produced by bending the neck forward. The sign suggests a lesion of the dorsal columns of the cervical cord or of the caudal medulla, correlating significantly with cervical MRI abnormalities.[104] Between 25 and 40% of MS patients report having Lhermitte's sign during the course of their illness.[105][106][107] It is not always experienced as painful, but about 16% of people with MS will experience painful Lhermitte's sign.[93]

Dysesthesias[edit]

Dysesthesias are disagreeable sensations produced by ordinary stimuli. The abnormal sensations are caused by lesions of the peripheral or central sensory pathways, and are described as painful feelings such as burning, wetness, itching, electric shock or pins and needles. Both Lhermitte's sign and painful dysesthesias usually respond well to treatment with carbamazepine, clonazepam or amitriptyline.[108][109][110] A related symptom is a pleasant, yet unsettling sensation which has no normal explanation (such as sensation of gentle warmth arising from touch by clothing)[citation needed]

Reduced sense of smell[edit]

People with Multiple Sclerosis have been found to have reduced sense of smell, including lower olfactory thresholds.[111][112][113]

Sexual[edit]

Sexual dysfunction (SD) is one of many symptoms affecting persons with a diagnosis of MS. SD in men encompasses both erectile and ejaculatory disorder. The prevalence of SD in men with MS ranges from 75 to 91%.[114] Erectile dysfunction appears to be the most common form of SD documented in MS. SD may be due to alteration of the ejaculatory reflex which can be affected by neurological conditions such as MS.[114] Sexual dysfunction is also prevalent in female MS patients, typically lack of orgasm, probably related to disordered genital sensation.

Spasticity[edit]

Spasticity is characterized by increased stiffness and slowness in limb movement, the development of certain postures, an association with weakness of voluntary muscle power, and with involuntary and sometimes painful spasms of limbs.[31] Painful spasms affect about 15% of people with MS overall.[93] A physiotherapist can help to reduce spasticity and avoid the development of contractures with techniques such as passive stretching.[115] There is evidence, albeit limited, of the clinical effectiveness of THC and CBD extracts,[116] baclofen,[117] dantrolene,[118] diazepam,[119] and tizanidine.[120][121][122] In the most complicated cases intrathecal injections of baclofen can be used.[123] There are also palliative measures like castings, splints or customized seatings.[31]

Speech and swallowing[edit]

Speech problems include slurred speech, low tone of voice (dysphonia), decreased talking speed, and problems with articulation of sounds (dysarthria).

A related problem, since it involves similar anatomical structures, is swallowing difficulties (dysphagia).[124]

Transverse myelitis[edit]

Some MS patients develop rapid onset of numbness, weakness, bowel or bladder dysfunction, and/or loss of muscle function, typically in the lower half of the body.[citation needed] This is the result of MS attacking the spinal cord. The symptoms and signs depend upon the nerve cords involved and the extent of the involvement.

Prognosis for complete recovery is generally poor. Recovery from transverse myelitis usually begins between weeks 2 and 12 following onset and may continue for up to 2 years in some patients and as many as 80% of individuals with transverse myelitis are left with lasting disabilities.[citation needed]

Though it was considered for many years that traverse myelitis was a normal consequence of MS, since the discovery of anti-AQP4 and anti-MOG biomarkers it is not. Now TM is considered an indicator of neuromyelitis optica, and a red flag against the diagnosis of MS.[125]

Tremor and ataxia[edit]

Tremor is an unintentional, somewhat rhythmic, muscle movement involving to-and-fro movements (oscillations) of one or more parts of the body. It is the most common of all involuntary movements and can affect the hands, arms, head, face, vocal cords, trunk, and legs. Ataxia is an unsteady and clumsy motion of the limbs or torso due to a failure of the gross coordination of muscle movements. People with ataxia experience a failure of muscle control in their arms and legs, resulting in a lack of balance and coordination or a disturbance of gait.

Tremor and ataxia are frequent in MS and present in 25 to 60% of patients. They can be very disabling and embarrassing, and are difficult to manage.[126] The origin of tremor in MS is difficult to identify but it can be due to a mixture of different factors such as damage to the cerebellar connections, weakness, spasticity, etc.

Many medications have been proposed to treat tremor; however their efficacy is very limited. Medications that have been reported to provide some relief are isoniazid,[127][128][129][130] carbamazepine,[97] propranolol[131][132][133] and gluthetimide[134] but published evidence of effectiveness is limited.[135] Physical therapy is not indicated as a treatment for tremor or ataxia although the use of orthese devices can help. An example is the use of wrist bandages with weights, which can be useful to increase the inertia of movement and therefore reduce tremor.[136] Daily use objects are also adapted so they are easier to grab and use.

If all these measures fail patients are candidates for thalamus surgery. This kind of surgery can be both a thalamotomy or the implantation of a thalamic stimulator. Complications are frequent (30% in thalamotomy and 10% in deep brain stimulation) and include a worsening of ataxia, dysarthria and hemiparesis. Thalamotomy is a more efficacious surgical treatment for intractable MS tremor though the higher incidence of persistent neurological deficits in patients receiving lesional surgery supports the use of deep brain stimulation as the preferred surgical strategy.[137]

References[edit]

- ^ Kurtzke JF (November 1983). "Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS)". Neurology. 33 (11): 1444–1452. doi:10.1212/WNL.33.11.1444. PMID 6685237.

- ^ Navarro S, Mondéjar-Marín B, Pedrosa-Guerrero A, Pérez-Molina I, Garrido-Robres JA, Alvarez-Tejerina A (2005). "[Aphasia and parietal syndrome as the presenting symptoms of a demyelinating disease with pseudotumoral lesions]". Revista de Neurologia. 41 (10): 601–603. PMID 16288423.

- ^ Jongen PJ (June 2006). "Psychiatric onset of multiple sclerosis". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 245 (1–2): 59–62. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2005.09.014. PMID 16631798. S2CID 33098365.

- ^ Paty D, Studney D, Redekop K, Lublin F (1994). "MS COSTAR: a computerized patient record adapted for clinical research purposes". Annals of Neurology. 36 (Suppl): S134–S135. doi:10.1002/ana.410360732. PMID 8017875. S2CID 23425667.

- ^ a b "Fatigue". mstrust.org.uk.

- ^ "Fatigue". Letchworth Garden City, United Kingdom: Multiple Sclerosis Trust.

- ^ Moore H, Nair KP, Baster K, Middleton R, Paling D, Sharrack B (August 2022). "Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: A UK MS-register based study". Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 64: 103954. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2022.103954. PMID 35716477.

- ^ Hubbard AL, Golla H, Lausberg H (June 2021). "What's in a name? That which we call Multiple Sclerosis Fatigue". Multiple Sclerosis. 27 (7): 983–988. doi:10.1177/1352458520941481. PMC 8142120. PMID 32672087.

- ^ Bakalidou D, Giannopapas V, Giannopoulos S (July 2023). "Thoughts on Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis Patients". Cureus. 15 (7): e42146. doi:10.7759/cureus.42146. PMC 10438195. PMID 37602098.

- ^ Tervonen T, Fox RJ, Brooks A, Sidorenko T, Boyanova N, Levitan B, et al. (2023). "Treatment preferences in relation to fatigue of patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: A discrete choice experiment". Multiple Sclerosis Journal - Experimental, Translational and Clinical. 9 (1): 20552173221150370. doi:10.1177/20552173221150370. PMC 9880588. PMID 36714174.

- ^ Manjaly ZM, Harrison NA, Critchley HD, Do CT, Stefanics G, Wenderoth N, et al. (June 2019). "Pathophysiological and cognitive mechanisms of fatigue in multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 90 (6): 642–651. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2018-320050. PMC 6581095. PMID 30683707.

- ^ Ellison PM, Goodall S, Kennedy N, Dawes H, Clark A, Pomeroy V, et al. (September 2022). "Neurostructural and Neurophysiological Correlates of Multiple Sclerosis Physical Fatigue: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Studies". Neuropsychology Review. 32 (3): 506–519. doi:10.1007/s11065-021-09508-1. PMC 9381450. PMID 33961198.

- ^ Newland P, Starkweather A, Sorenson M (July 2016). "Central fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a review of the literature". The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine. 39 (4): 386–399. doi:10.1080/10790268.2016.1168587. PMC 5102292. PMID 27146427.

- ^ Chen MH, Wylie GR, Sandroff BM, Dacosta-Aguayo R, DeLuca J, Genova HM (August 2020). "Neural mechanisms underlying state mental fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a pilot study". Journal of Neurology. 267 (8): 2372–2382. doi:10.1007/s00415-020-09853-w. PMID 32350648.

- ^ a b Christogianni A, O'Garro J, Bibb R, Filtness A, Filingeri D (November 2022). "Heat and cold sensitivity in multiple sclerosis: A patient-centred perspective on triggers, symptoms, and thermal resilience practices". Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 67: 104075. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2022.104075. PMID 35963205.

- ^ Davis SL, Wilson TE, White AT, Frohman EM (November 2010). "Thermoregulation in multiple sclerosis". Journal of Applied Physiology. 109 (5): 1531–1537. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00460.2010. PMC 2980380. PMID 20671034.

- ^ "Heat Sensitivity". Archived from the original on 2024-01-17. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ Trust MS. "Temperature sensitivity | MS Trust". mstrust.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2024-01-17. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ "Temperature sensitivity". mstrust.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2024-01-17. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ Sumowski JF, Leavitt VM (July 2014). "Body temperature is elevated and linked to fatigue in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, even without heat exposure". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 95 (7): 1298–1302. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2014.02.004. PMC 4071126. PMID 24561056.

- ^ Leavitt VM, De Meo E, Riccitelli G, Rocca MA, Comi G, Filippi M, et al. (November 2015). "Elevated body temperature is linked to fatigue in an Italian sample of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients". Journal of Neurology. 262 (11): 2440–2442. doi:10.1007/s00415-015-7863-8. PMID 26223805.

- ^ Loy BD, Taylor RL, Fling BW, Horak FB (September 2017). "Relationship between perceived fatigue and performance fatigability in people with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 100: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.06.017. PMC 5875709. PMID 28789787.

- ^ Patejdl R, Zettl UK (2022). "The pathophysiology of motor fatigue and fatigability in multiple sclerosis". Frontiers in Neurology. 13: 891415. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.891415. PMC 9363784. PMID 35968278.

- ^ "Empowering people affected by MS to live their best lives". National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

- ^ "Fatigue in Patients With Multiple Sclerosis". Practical Neurology.

- ^ "Relapsing remitting MS (RRMS)". mssociety.org. Retrieved 2024-04-23.

- ^ "Fatigue in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis".

- ^ Chalah MA, Riachi N, Ahdab R, Créange A, Lefaucheur JP, Ayache SS (2015). "Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis: Neural Correlates and the Role of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 9: 460. doi:10.3389/fncel.2015.00460. PMC 4663273. PMID 26648845.

- ^ Gerber LH, Weinstein AA, Mehta R, Younossi ZM (July 2019). "Importance of fatigue and its measurement in chronic liver disease". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 25 (28): 3669–3683. doi:10.3748/wjg.v25.i28.3669. PMC 6676553. PMID 31391765.

- ^ Hartvig Honoré P (June 2013). "Fatigue". European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 20 (3): 147–148. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2013-000309. S2CID 220171226.

- ^ a b c The Royal College of Physicians (2004). Multiple Sclerosis. National clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care (PDF). Salisbury, Wiltshire: Sarum ColourView Group. ISBN 978-1-86016-182-7.

- ^ Bakshi R (June 2003). "Fatigue associated with multiple sclerosis: diagnosis, impact and management". Multiple Sclerosis. 9 (3): 219–227. doi:10.1191/1352458503ms904oa. PMID 12814166. S2CID 40931716.

- ^ Mohr DC, Hart SL, Goldberg A (2003). "Effects of treatment for depression on fatigue in multiple sclerosis". Psychosomatic Medicine. 65 (4): 542–547. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.318.5928. doi:10.1097/01.PSY.0000074757.11682.96. PMID 12883103. S2CID 16239318.

- ^ Palotai M, Guttmann CR (June 2020). "Brain anatomical correlates of fatigue in multiple sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis. 26 (7): 751–764. doi:10.1177/1352458519876032. PMID 31536461.

- ^ Camera V, Mariano R, Messina S, Menke R, Griffanti L, Craner M, et al. (2023). "Shared imaging markers of fatigue across multiple sclerosis, aquaporin-4 antibody neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and MOG antibody disease". Brain Communications. 5 (3): fcad107. doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcad107. PMC 10171455. PMID 37180990.

- ^ Preziosa P, Rocca MA, Pagani E, Valsasina P, Amato MP, Brichetto G, et al. (March 2023). "Structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging correlates of fatigue and dual-task performance in progressive multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology. 270 (3): 1543–1563. doi:10.1007/s00415-022-11486-0. hdl:10026.1/20405. PMID 36436069.

- ^ Novo AM, Batista S, Alves C, d'Almeida OC, Marques IB, Macário C, et al. (December 2018). "The neural basis of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: A multimodal MRI approach". Neurology. Clinical Practice. 8 (6): 492–500. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000545. PMC 6294533. PMID 30588379.

- ^ Bisecco A, Caiazzo G, d'Ambrosio A, Sacco R, Bonavita S, Docimo R, et al. (November 2016). "Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: The contribution of occult white matter damage". Multiple Sclerosis. 22 (13): 1676–1684. doi:10.1177/1352458516628331. PMID 26846989.

- ^ Rocca MA, Parisi L, Pagani E, Copetti M, Rodegher M, Colombo B, et al. (November 2014). "Regional but not global brain damage contributes to fatigue in multiple sclerosis". Radiology. 273 (2): 511–520. doi:10.1148/radiol.14140417. PMID 24927473.

- ^ Muñoz Maniega S, Chappell FM, Valdés Hernández MC, Armitage PA, Makin SD, Heye AK, et al. (February 2017). "Integrity of normal-appearing white matter: Influence of age, visible lesion burden and hypertension in patients with small-vessel disease". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 37 (2): 644–656. doi:10.1177/0271678X16635657. PMC 5381455. PMID 26933133.

- ^ Sepulcre J, Masdeu JC, Goñi J, Arrondo G, Vélez de Mendizábal N, Bejarano B, et al. (March 2009). "Fatigue in multiple sclerosis is associated with the disruption of frontal and parietal pathways". Multiple Sclerosis. 15 (3): 337–344. doi:10.1177/1352458508098373. PMID 18987107. S2CID 2701289.

- ^ Pucci E, Branãs P, D'Amico R, Giuliani G, Solari A, Taus C (January 2007). Pucci E (ed.). "Amantadine for fatigue in multiple sclerosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (1): CD002818. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002818.pub2. PMC 6991937. PMID 17253480.

- ^ "Amantadine". Medline. US National Library of Medicine. April 2003. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- ^ Weinshenker BG, Penman M, Bass B, Ebers GC, Rice GP (August 1992). "A double-blind, randomized, crossover trial of pemoline in fatigue associated with multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 42 (8): 1468–1471. doi:10.1212/wnl.42.8.1468. PMID 1641137. S2CID 41990406.

- ^ "Pemoline". Medline. US National Library of Medicine. January 2006. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- ^ a b "Comparing Treatments for Multiple Sclerosis-Related Fatigue - Evidence Update for Clinicians | PCORI". www.pcori.org. 2023-09-01. Retrieved 2023-11-30.

- ^ Mathiowetz VG, Finlayson ML, Matuska KM, Chen HY, Luo P (October 2005). "Randomized controlled trial of an energy conservation course for persons with multiple sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis. 11 (5): 592–601. doi:10.1191/1352458505ms1198oa. PMID 16193899. S2CID 33902095.

- ^ Matuska K, Mathiowetz V, Finlayson M (2007). "Use and perceived effectiveness of energy conservation strategies for managing multiple sclerosis fatigue". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 61 (1): 62–69. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.1.62. PMID 17302106.

- ^ Pinarello C, Elmers J, Inojosa H, Beste C, Ziemssen T (2023). "Management of multiple sclerosis fatigue in the digital age: from assessment to treatment". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 17: 1231321. doi:10.3389/fnins.2023.1231321. PMC 10585158. PMID 37869507.

- ^ Hennessey A, Robertson NP, Swingler R, Compston DA (November 1999). "Urinary, faecal and sexual dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology. 246 (11): 1027–1032. doi:10.1007/s004150050508. PMID 10631634. S2CID 30179761.

- ^ Burguera-Hernández JA (2000). "[Urinary alterations in multiple sclerosis]". Revista de Neurologia (in Spanish). 30 (10): 989–992. doi:10.33588/rn.3010.99371. PMID 10919202.

- ^ Betts CD, D'Mellow MT, Fowler CJ (March 1993). "Urinary symptoms and the neurological features of bladder dysfunction in multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 56 (3): 245–250. doi:10.1136/jnnp.56.3.245. PMC 1014855. PMID 8459239.

- ^ Nour S, Svarer C, Kristensen JK, Paulson OB, Law I (April 2000). "Cerebral activation during micturition in normal men". Brain. 123 ( Pt 4) (4): 781–789. doi:10.1093/brain/123.4.781. PMID 10734009.

- ^ Ayuso-Peralta L, de Andrés C (2002). "[Symptomatic treatment of multiple sclerosis]". Revista de Neurologia (in Spanish). 35 (12): 1141–1153. doi:10.33588/rn.3512.2002385. PMID 12497297.

- ^ "Alfuzosin". MedlinePlus Drug Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Trospium". MedlinePlus Drug Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Flavoxate". MedlinePlus Drug Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Bosma R, Wynia K, Havlíková E, De Keyser J, Middel B (July 2005). "Efficacy of desmopressin in patients with multiple sclerosis suffering from bladder dysfunction: a meta-analysis". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 112 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00431.x. hdl:11370/1eb88003-4dfb-4de1-9aa2-1100972e8666. PMID 15932348. S2CID 46673620.

- ^ "Desmopressin". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Dyro FM (8 August 2019). Egan RA (ed.). "Urologic Management in Neurologic Disease: Overview, Neuroanatomy of Pelvic Floor, Neurophysiology of Pelvic Floor" – via eMedicine.

- ^ a b c d The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions (UK) (2004). "Diagnosis and treatment of specific impairments". Multiple sclerosis: national clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care (PDF). NICE Clinical Guidelines. Vol. 8. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK). pp. 87–132. ISBN 978-1-86016-182-7. PMID 21290636. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ DasGupta R, Fowler CJ (2003). "Bladder, bowel and sexual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: management strategies". Drugs. 63 (2): 153–166. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363020-00003. PMID 12515563. S2CID 46351374.

- ^ Bobholz JA, Rao SM (June 2003). "Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments". Current Opinion in Neurology. 16 (3): 283–288. doi:10.1097/00019052-200306000-00006. PMID 12858063.

- ^ Chen MH, Wylie GR, Sandroff BM, Dacosta-Aguayo R, DeLuca J, Genova HM (August 2020). "Neural mechanisms underlying state mental fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a pilot study". Journal of Neurology. 267 (8): 2372–2382. doi:10.1007/s00415-020-09853-w. PMID 32350648.

- ^ a b c Amato MP, Ponziani G, Siracusa G, Sorbi S (October 2001). "Cognitive dysfunction in early-onset multiple sclerosis: a reappraisal after 10 years". Archives of Neurology. 58 (10): 1602–1606. doi:10.1001/archneur.58.10.1602. PMID 11594918.

- ^ a b Benedict RH, Carone DA, Bakshi R (July 2004). "Correlating brain atrophy with cognitive dysfunction, mood disturbances, and personality disorder in multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neuroimaging. 14 (3 Suppl): 36S–45S. doi:10.1177/1051228404266267 (inactive 2024-02-28). PMID 15228758.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2024 (link) - ^ Shawaryn MA, Schultheis MT, Garay E, Deluca J (August 2002). "Assessing functional status: exploring the relationship between the multiple sclerosis functional composite and driving". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 83 (8): 1123–1129. doi:10.1053/apmr.2002.33730. PMID 12161835.

- ^ Rao SM, Leo GJ, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F (May 1991). "Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. I. Frequency, patterns, and prediction". Neurology. 41 (5): 685–691. doi:10.1212/wnl.41.5.685. PMID 2027484. S2CID 9962959.

- ^ Dujardin K, Donze AC, Hautecoeur P (January 1998). "Attention impairment in recently diagnosed multiple sclerosis". European Journal of Neurology. 5 (1): 61–66. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.1998.510061.x. PMID 10210813. S2CID 33389996.

- ^ Achiron A, Barak Y (April 2003). "Cognitive impairment in probable multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 74 (4): 443–446. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.4.443. PMC 1738365. PMID 12640060.

- ^ Kletenik I, Cohen AL, Glanz BI, Ferguson MA, Tauhid S, Li J, et al. (November 2023). "Multiple sclerosis lesions that impair memory map to a connected memory circuit". Journal of Neurology. 270 (11): 5211–5222. doi:10.1007/s00415-023-11907-8. PMC 10592111. PMID 37532802. S2CID 260433348.

- ^ a b Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J (December 2008). "Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis". The Lancet. Neurology. 7 (12): 1139–1151. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70259-X. PMID 19007738. S2CID 25783642.

- ^ Sadovnick AD, Remick RA, Allen J, Swartz E, Yee IM, Eisen K, et al. (March 1996). "Depression and multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 46 (3): 628–632. doi:10.1212/wnl.46.3.628. PMID 8618657. S2CID 33587300.

- ^ Patten SB, Beck CA, Williams JV, Barbui C, Metz LM (December 2003). "Major depression in multiple sclerosis: a population-based perspective". Neurology. 61 (11): 1524–1527. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.581.3646. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000095964.34294.b4. PMID 14663036. S2CID 1602489.

- ^ Siegert RJ, Abernethy DA (April 2005). "Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 76 (4): 469–475. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.054635. PMC 1739575. PMID 15774430.

- ^ Sadovnick AD, Eisen K, Ebers GC, Paty DW (August 1991). "Cause of death in patients attending multiple sclerosis clinics". Neurology. 41 (8): 1193–1196. doi:10.1212/wnl.41.8.1193. PMID 1866003. S2CID 31905744.

- ^ Murray ED, Buttner N, Price BH. (2012) Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice. In: Neurology in Clinical Practice, 6th Edition. Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J (eds.) Butterworth Heinemann. April 12, 2012. ISBN 1437704344 | ISBN 978-1437704341

- ^ Leigh RJ, Averbuch-Heller L, Tomsak RL, Remler BF, Yaniglos SS, Dell'Osso LF (August 1994). "Treatment of abnormal eye movements that impair vision: strategies based on current concepts of physiology and pharmacology". Annals of Neurology. 36 (2): 129–141. doi:10.1002/ana.410360204. PMID 8053648. S2CID 23670958.

- ^ Starck M, Albrecht H, Pöllmann W, Straube A, Dieterich M (January 1997). "Drug therapy for acquired pendular nystagmus in multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology. 244 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1007/PL00007728. PMID 9007739. S2CID 12333107.

- ^ a b Clanet MG, Brassat D (June 2000). "The management of multiple sclerosis patients". Current Opinion in Neurology. 13 (3): 263–270. doi:10.1097/00019052-200006000-00005. PMID 10871249.

- ^ Menon GJ, Thaller VT (November 2002). "Therapeutic external ophthalmoplegia with bilateral retrobulbar botulinum toxin- an effective treatment for acquired nystagmus with oscillopsia". Eye. 16 (6): 804–806. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6700167. PMID 12439689.

- ^ Jain S, Proudlock F, Constantinescu CS, Gottlob I (November 2002). "Combined pharmacologic and surgical approach to acquired nystagmus due to multiple sclerosis". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 134 (5): 780–782. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01629-X. PMID 12429265.

- ^ Weinshenker BG, Bass B, Rice GP, Noseworthy J, Carriere W, Baskerville J, et al. (February 1989). "The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. I. Clinical course and disability". Brain. 112 ( Pt 1) (1): 133–146. doi:10.1093/brain/112.1.133. PMID 2917275.

- ^ Freeman JA (April 2001). "Improving mobility and functional independence in persons with multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology. 248 (4): 255–259. doi:10.1007/s004150170198. PMID 11374088. S2CID 12461962.

- ^ Beck RW, Trobe JD (October 1995). "What we have learned from the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial". Ophthalmology. 102 (10): 1504–1508. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30839-1. PMID 9097798.

- ^ "The 5-year risk of MS after optic neuritis: experience of the optic neuritis treatment trial. 1997". Neurology. 57 (12 Suppl 5): S36–S45. December 2001. PMID 11902594.

- ^ Cervetto L, Demontis GC, Gargini C (February 2007). "Cellular mechanisms underlying the pharmacological induction of phosphenes". British Journal of Pharmacology. 150 (4): 383–390. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706998. PMC 2189731. PMID 17211458.

- ^ "An intereye difference of 5–6 μm in RNFL thickness is a robust structural threshold for identifying the presence of a unilateral optic nerve lesion in MS." Nolan RC, Galetta SL, Frohman TC, Frohman EM, Calabresi PA, Castrillo-Viguera C, et al. (December 2018). "Optimal Intereye Difference Thresholds in Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness for Predicting a Unilateral Optic Nerve Lesion in Multiple Sclerosis". Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 38 (4): 451–458. doi:10.1097/WNO.0000000000000629. PMC 8845082. PMID 29384802.

- ^ Jiang H, Delgado S, Wang J (February 2021). "Advances in ophthalmic structural and functional measures in multiple sclerosis: do the potential ocular biomarkers meet the unmet needs?". Current Opinion in Neurology. 34 (1): 97–107. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000897. PMC 7856092. PMID 33278142.

- ^ Nij Bijvank J, Uitdehaag BM, Petzold A (February 2022). "Retinal inter-eye difference and atrophy progression in multiple sclerosis diagnostics". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 93 (2): 216–219. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2021-327468. PMC 8785044. PMID 34764152.

- ^ Bsteh G, Hegen H, Altmann P, Auer M, Berek K, Pauli FD, et al. (October 19, 2020). "Retinal layer thinning is reflecting disability progression independent of relapse activity in multiple sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis Journal - Experimental, Translational and Clinical. 6 (4): 2055217320966344. doi:10.1177/2055217320966344. PMC 7604994. PMID 33194221.

- ^ Martinez-Lapiscina EH, Arnow S, Wilson JA, Saidha S, Preiningerova JL, Oberwahrenbrock T, et al. (May 2016). "Retinal thickness measured with optical coherence tomography and risk of disability worsening in multiple sclerosis: a cohort study". The Lancet. Neurology. 15 (6): 574–584. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00068-5. PMID 27011339.

- ^ a b c d e Foley PL, Vesterinen HM, Laird BJ, Sena ES, Colvin LA, Chandran S, et al. (May 2013). "Prevalence and natural history of pain in adults with multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis". Pain. 154 (5): 632–642. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2012.12.002. PMID 23318126. S2CID 25807525.

- ^ Archibald CJ, McGrath PJ, Ritvo PG, Fisk JD, Bhan V, Maxner CE, et al. (July 1994). "Pain prevalence, severity and impact in a clinic sample of multiple sclerosis patients". Pain. 58 (1): 89–93. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(94)90188-0. PMID 7970843. S2CID 25295712.

- ^ "MS Hug: 7 Tips for Relieving MS Hug Symptoms". November 25, 2022.

- ^ Kerns RD, Kassirer M, Otis J (2002). "Pain in multiple sclerosis: a biopsychosocial perspective". Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 39 (2): 225–232. PMID 12051466.

- ^ a b "Carbamazepine". MedlinePlus Drug Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Phenytoin". MedlinePlus Drug Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Gabapentin". MedlinePlus Drug Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Solaro C, Messmer Uccelli M, Uccelli A, Leandri M, Mancardi GL (2000). "Low-dose gabapentin combined with either lamotrigine or carbamazepine can be useful therapies for trigeminal neuralgia in multiple sclerosis". European Neurology. 44 (1): 45–48. doi:10.1159/000008192. hdl:11567/301010. PMID 10894995. S2CID 39508538.

- ^ Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD, Bissonette DJ (May 1994). "Long-term results after glycerol rhizotomy for multiple sclerosis-related trigeminal neuralgia". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. Le Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques. 21 (2): 137–140. doi:10.1017/S0317167100049076. PMID 8087740.

- ^ Athanasiou TC, Patel NK, Renowden SA, Coakham HB (December 2005). "Some patients with multiple sclerosis have neurovascular compression causing their trigeminal neuralgia and can be treated effectively with MVD: report of five cases". British Journal of Neurosurgery. 19 (6): 463–468. doi:10.1080/02688690500495067. PMID 16574557. S2CID 33819410.

- ^ Eldridge PR, Sinha AK, Javadpour M, Littlechild P, Varma TR (2003). "Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia in patients with multiple sclerosis". Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery. 81 (1–4): 57–64. doi:10.1159/000075105. PMID 14742965. S2CID 39449873.

- ^ Gutrecht JA, Zamani AA, Slagado ED (August 1993). "Anatomic-radiologic basis of Lhermitte's sign in multiple sclerosis". Archives of Neurology. 50 (8): 849–851. doi:10.1001/archneur.1993.00540080056014. PMID 8352672.

- ^ Al-Araji AH, Oger J (August 2005). "Reappraisal of Lhermitte's sign in multiple sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis. 11 (4): 398–402. doi:10.1191/1352458505ms1177oa. PMID 16042221. S2CID 33610136.

- ^ Sandyk R, Dann LC (April 1995). "Resolution of Lhermitte's sign in multiple sclerosis by treatment with weak electromagnetic fields". The International Journal of Neuroscience. 81 (3–4): 215–224. doi:10.3109/00207459509004888. PMID 7628912.

- ^ Kanchandani R, Howe JG (April 1982). "Lhermitte's sign in multiple sclerosis: a clinical survey and review of the literature". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 45 (4): 308–312. doi:10.1136/jnnp.45.4.308. PMC 491365. PMID 7077340.

- ^ "Clonazepam". MedlinePlus Drug Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Amitriptyline". MedlinePlus Drug Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Moulin DE, Foley KM, Ebers GC (December 1988). "Pain syndromes in multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 38 (12): 1830–1834. doi:10.1212/wnl.38.12.1830. PMID 2973568. S2CID 647138.

- ^ Schmidt FA, Maas MB, Geran R, Schmidt C, Kunte H, Ruprecht K, et al. (July 2017). "Olfactory dysfunction in patients with primary progressive MS". Neurology. 4 (4): e369. doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000369. PMC 5471346. PMID 28638852. S2CID 1080966.

- ^ "Smell test might predict DMT affectiveness". 4 April 2022.

- ^ Atalar AÇ, Erdal Y, Tekin B, Yıldız M, Akdoğan Ö, Emre U (April 2018). "Olfactory dysfunction in multiple sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 21: 92–96. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2018.02.032. PMID 29529530.

- ^ a b O'Leary M, Heyman R, Erickson J, Chancellor MB (June 2007). Premature Ejaculation and MS: A Review (PDF) (Report). Consortium of MS Centers.

- ^ Cardini RG, Crippa AC, Cattaneo D (May 2000). "Update on multiple sclerosis rehabilitation". Journal of Neurovirology. 6 (Suppl 2): S179–S185. PMID 10871810.

- ^ Lakhan SE, Rowland M (December 2009). "Whole plant cannabis extracts in the treatment of spasticity in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". BMC Neurology. 9: 59. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-9-59. PMC 2793241. PMID 19961570.

- ^ "Baclofen oral". Medline. U.S. National Library of Medicine. April 2003. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- ^ "Dantrolene oral". Medline. U.S. National Library of Medicine. April 2003. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- ^ "Diazepam". Medline. U.S. National Library of Medicine. April 2003. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- ^ "Tizanidine". Medline. U.S. National Library of Medicine. April 2003. Retrieved 17 October 2007..

- ^ Beard S, Hunn A, Wight J (2003). "Treatments for spasticity and pain in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". Health Technology Assessment. 7 (40): iii, ix–x, 1–111. doi:10.3310/hta7400. PMID 14636486.

- ^ Paisley S, Beard S, Hunn A, Wight J (August 2002). "Clinical effectiveness of oral treatments for spasticity in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review". Multiple Sclerosis. 8 (4): 319–329. doi:10.1191/1352458502ms795rr. PMID 12166503. S2CID 1641319.

- ^ Becker WJ, Harris CJ, Long ML, Ablett DP, Klein GM, DeForge DA (August 1995). "Long-term intrathecal baclofen therapy in patients with intractable spasticity". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. Le Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques. 22 (3): 208–217. doi:10.1017/S031716710003986X. PMID 8529173.

- ^ Richard Senelick (Reviewer) (Aug 2012). "The Speech and Swallowing Problems of Multiple Sclerosis". Web MD. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Asnafi S, Morris PP, Sechi E, Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG, Palace J, et al. (January 2020). "The frequency of longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis in MS: A population-based study". Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 37: 101487. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2019.101487. PMID 31707235.

- ^ Koch M, Mostert J, Heersema D, De Keyser J (February 2007). "Tremor in multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology. 254 (2): 133–145. doi:10.1007/s00415-006-0296-7. PMC 1915650. PMID 17318714.

- ^ Bozek CB, Kastrukoff LF, Wright JM, Perry TL, Larsen TA (January 1987). "A controlled trial of isoniazid therapy for action tremor in multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology. 234 (1): 36–39. doi:10.1007/BF00314007. PMID 3546605. S2CID 23597601.

- ^ Duquette P, Pleines J, du Souich P (December 1985). "Isoniazid for tremor in multiple sclerosis: a controlled trial". Neurology. 35 (12): 1772–1775. doi:10.1212/wnl.35.12.1772. PMID 3906430. S2CID 24266989.

- ^ Hallett M, Lindsey JW, Adelstein BD, Riley PO (September 1985). "Controlled trial of isoniazid therapy for severe postural cerebellar tremor in multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 35 (9): 1374–1377. doi:10.1212/wnl.35.9.1374. PMID 3895037. S2CID 30254514.

- ^ "Isoniazid". Medline. U.S. National Library of Medicine. April 2003. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- ^ Koller WC (March 1984). "Pharmacologic trials in the treatment of cerebellar tremor". Archives of Neurology. 41 (3): 280–281. doi:10.1001/archneur.1984.04050150058017. PMID 6365047.

- ^ Sechi GP, Zuddas M, Piredda M, Agnetti V, Sau G, Piras ML, et al. (August 1989). "Treatment of cerebellar tremors with carbamazepine: a controlled trial with long-term follow-up". Neurology. 39 (8): 1113–1115. doi:10.1212/wnl.39.8.1113. PMID 2668787. S2CID 36050520.

- ^ "Propranolol (Cardiovascular)". MedlinePlus Drug Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Aisen ML, Holzer M, Rosen M, Dietz M, McDowell F (May 1991). "Glutethimide treatment of disabling action tremor in patients with multiple sclerosis and traumatic brain injury". Archives of Neurology. 48 (5): 513–515. doi:10.1001/archneur.1991.00530170077023. PMID 2021365.

- ^ Mills RJ, Yap L, Young CA (January 2007). Mills RJ (ed.). "Treatment for ataxia in multiple sclerosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD005029. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005029.pub2. PMID 17253537.

- ^ Aisen ML, Arnold A, Baiges I, Maxwell S, Rosen M (July 1993). "The effect of mechanical damping loads on disabling action tremor". Neurology. 43 (7): 1346–1350. doi:10.1212/wnl.43.7.1346. PMID 8327136. S2CID 23433712.

- ^ Bittar RG, Hyam J, Nandi D, Wang S, Liu X, Joint C, et al. (August 2005). "Thalamotomy versus thalamic stimulation for multiple sclerosis tremor". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 12 (6): 638–642. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2004.09.008. PMID 16098758. S2CID 38770179.