Norton Motorcycle Company

| |

| |

| Company type | Private company |

|---|---|

| Industry | Motorcycles |

| Founded |

|

| Founder | James Lansdowne Norton |

| Headquarters | Solihull, West Midlands, England[1] |

| Parent | TVS Motor Company |

| Website | www |

The Norton Motorcycle Company (formerly Norton Motorcycles.) is a brand of motorcycles headquartered in Solihull, West Midlands, (originally based in Birmingham), England. For some years around 1990, the rights to use the name on motorcycles were owned by North American financiers. Currently it is owned by Indian motorcycle giant TVS Motor Company

The business was founded in 1898 as a "fittings and parts for the two-wheel trade" manufacturer.[2] By 1902 the company had begun manufacturing motorcycles with bought-in engines. In 1908 a Norton-built engine was added to the range. This began a long series of production of single and eventually twin-cylinder motorcycles, and a long history of racing involvement. During the Second World War Norton produced almost 100,000 of the military Model 16 H and Big 4 sidevalve motorcycles.

Associated Motor Cycles bought the company in 1953.[3] It was reformed as Norton-Villiers, part of Manganese Bronze Holdings, in 1966, and merged with BSA to form Norton Villiers Triumph in 1973.

In late 2008, Stuart Garner, a UK businessman, bought the rights to Norton from some US concerns and relaunched Norton in its then-new Midlands home at Donington Park where it was to develop the 961cc Norton Commando and a new range of Norton motorcycles.[4]

The company went into administration in January 2020.[5] In April 2020, administrators BDO agreed to sell certain aspects of Garner's business to a new business with links to Indian motorcycle producer TVS Motor Company.[6][7]

Early history

[edit]

The original company was formed by James Lansdowne Norton (known as "Pa") at 320, Bradford Street, Birmingham, in 1898.[2] In 1902 Norton began building motorcycles with French and Swiss engines. In 1907 a Norton with Peugot engine, ridden by Rem Fowler, won the twin-cylinder class in the first Isle of Man TT race, beginning a sporting tradition that went on until the 1960s. In April 1907 the Norton Manufacturing Co. moved to a larger factory at Deritend Bridge, Floodgate Street, Birmingham.[8] The first Norton engines were made in 1907, with production models available from 1908. These were the 3.5 hp (490 cc) and the 'Big 4' (633cc), beginning a line of side-valve single-cylinder engines which continued with few changes until the late 1950s.[3]

The first Norton logo was a fairly simple, art nouveau design, with the name spelled in capitals.[9] However, a new logo appeared on the front of the catalogue for 1914, which was a joint effort by James Norton and his daughter Ethel. It became known as the "curly N" logo, with only the initial letter as a capital, and was used by the company thereafter, first appearing on actual motorcycles in 1915.[10]

In 1913 the business declined, and R. T. Shelley & Co., the main creditors, intervened and saved it. Norton Motors Ltd was formed shortly afterwards under joint directorship of James Norton and Bob Shelley. Shelley's brother-in-law was tuner Dan O'Donovan, and he managed to set a significant number of records on the Norton by 1914 when the war broke out - and as competition motorcycling was largely suspended during the hostilities, these records still stood when production restarted after the war.[11] 1914 Dan O'Donovan records set in April 1914 :

- Under 500 cc flying km 81.06 mph, flying mile 78.60 mph - 490 cc Norton

- Under 750 cc flying km and flying mile see above

- Under 500 cc with sidecar flying km 65.65 mph, flying mile 62.07 mph - 490 cc Norton

- Under 750 cc with sidecar flying km and flying mile see above

On 17 July 1914 O'Donovan also took the flying 5 mile record at 75.88 mph, and the standing start 10 mile record at 73.29 mph, again on the 490 cc Norton.

First World War

[edit]Norton continued production of their 3.5 hp and Big 4 singles well into the war period, though in November 1916 the Ministry of Munitions issued an order that no further work on motor cycles or cars would be allowed from 15 November 1916 without a permit.[12] By this time most motor cycle companies were already either producing munitions (or aircraft parts), or devoted to the export trade. Norton were involved in exporting and earlier that year had announced[13] a new 'Colonial Model' of their 633cc Big 4. This featured an increase in ground clearance from 4.25" to 6.5", by altering the frame, larger tank, greater clearance on mudguards, and a sturdy rear carrier. The engine was unaltered, and transmission was via a Sturmey-Archer 3-speed gearbox.

In February 1918, Motor Cycle reported[14] on a visit to Norton Motors. Mr Norton had stated that he expected three post-war models, the 3.5 hp 490 cc TT with belt drive (for the 'speed merchant'), and two utility mounts, one with detuned TT engine, and the other being the Big Four for very heavy solo or sidecar work, both of these with three-speed Sturmey-Archer countershaft gearbox and all chain drive. It was also stated that he had been experimenting with aluminium pistons, and that Norton had produced a book of driving hints which also contained details of their Military and Empire models.

In May 1918, Norton stated in one of their adverts[15] that 'The ministry are taking the whole of our present output, but we have a waiting list'; this advert also uses the "Unapproachable Norton" phrase. Few Norton WD models appear in the For Sale column of The Motor Cycle after the war, suggesting they were shipped abroad, apparently one order going to the Russian Army [1][permanent dead link]. The 1913–1917 Red Book[16] listing UK Motor, Marine and Aircraft production shows Norton dropped from a full range in 1916, to only the Military Big Four in 1917.

Inter-War years

[edit]Norton resumed deliveries of civilian motorcycles in April 1919 with models aimed at motorcyclists who enjoyed the reliability and performance offered by long-stroke single-cylinder engines with separate gearboxes.

Norton also resumed racing and in 1924 the Isle of Man Senior TT was the first win with a race average speed over 60 mph, rider Alec Bennett. Norton won this event ten times until they withdrew from racing in 1938.

J.L. Norton died in 1925 aged only 56, but he saw his motorcycles win the Senior and sidecar TTs in 1924,[17] specifically with the 500 cc Model 18, Norton's first overhead valve single.[18]

Designed by Walter Moore, the Norton CS1 engine appeared in 1927, based closely on the ES2 pushrod engine and using many of its parts. Moore was hired away to NSU in 1930, after which Arthur Carroll designed an entirely new OHC engine destined to become the basis for all later OHC and DOHC Norton singles. (Moore's move to NSU prompted his former staff to quip NSU stood for "Norton Spares Used") The Norton racing legend began in the 1930s. Of the nine Isle of Man Senior TTs (500 cc) between 1931 and 1939, Norton won seven.[19]

Until 1934 Norton bought Sturmey-Archer gearboxes and clutches. When Sturmey discontinued production Norton bought the design rights and had them made by Burman, a manufacturer of proprietary gearboxes.

Second World War

[edit]

Norton started making military motorcycles again in 1936 after a tender process in 1935 where a modified Norton 16H beat contenders. From 900 in 1936 to 2000 in 1937, Norton was ahead of the competition as war loomed, and there was good reason in terms of spares and maintenance for the military to keep to the same model. Between 1937 and 1945 nearly a quarter (over 100,000) of all British military motorcycles were Nortons, basically the WD 16H (solo) and WD Big Four outfit with driven sidecar wheel.[3]

Post-war

[edit]

The Isle of Man Senior TT successes continued after the war, with Nortons winning every year from 1947 to 1954.

After the Second World War, Norton reverted to civilian motorcycle production, gradually increasing its range. A major addition in 1949 was the twin cylinder Model 7, known as the Norton Dominator, a pushrod 500 cc twin-cylinder machine designed by Bert Hopwood. Its chassis was derived from the ES2 single, with telescopic front and plunger rear suspension, and an updated version of the gearbox known as the "lay-down" box. More shapely mudguards and tanks completed the more modern styling to Nortons new premium model twin.

Norton struggled to reclaim its pre-WWII racing dominance as the single-cylinder machine faced fierce competition from the multi-cylinder Italian machines and AJS from the UK. In the 1949 Grand Prix motorcycle racing season, the first year of the world championship, Norton made only fifth place and AJS won. That was before the Featherbed frame appeared, developed for Norton by the McCandless brothers of Belfast in January 1950, used in the legendary Manx Norton and raced by riders including Geoff Duke, John Surtees and Derek Minter. Very quickly the featherbed frame, a design that allowed the construction of a motorcycle with good mass-stiffness distribution,[20] became a benchmark by which all other frames were judged.[19]

Norton also experimented with engine placement, and discovered that moving the engine slightly up/down, forward/back, or even right/left, could deliver a "sweet spot" in terms of handling. Motorcycle designers still use this method to fine-tune motorcycle handling.[21]

In 1951 the Norton Dominator was made available to export markets as the Model 88 with the Featherbed frame. Later, as production of this frame increased, it became a regular production model, and was made in variants for other models, including the OHV single-cylinder machines.

Manx Nortons also played a significant role in the development of post war car racing. At the end of 1950, the English national 500 cc regulations were adopted as the new Formula 3. The JAP Speedway engine had dominated the category initially but the Manx was capable of producing significantly more power and became the engine of choice. Many complete motorcycles were bought in order to strip the engine for 500 cc car racing, as Norton would not sell separate engines.

The racing successes were transferred to the street through cafe racers, some of which would use the featherbed frame with an engine from another manufacturer to make a hybrid machine with the best of both worlds. The most famous of these were Tritons - Triumph twin engines in a Norton featherbed frame.

-

Civilianised version of 1943/44 military Norton, model WD16H

-

1954 Norton Manx

-

Norton Manx 500 cc Racer 1958

-

Pre-unit Triumph engined Triton Café racer

-

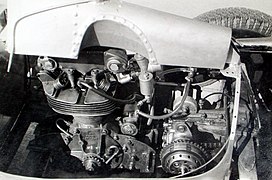

Norton Manx Engine in a Cooper Formula 500 Race Car

-

Detail of engine installation in the Cooper

AMC

[edit]

Despite, or perhaps because of, the racing successes Norton was in financial difficulty. Reynolds could not make many of the highly desired Featherbed frames and customers lost interest in buying machines with the older frames. In 1953 Norton sold out to Associated Motorcycles (AMC), who owned the brands AJS, Matchless, Francis-Barnett and James. In 1962 the Norton factory in Bracebridge Street, Birmingham was closed and production was moved to AMC's Woolwich factory in south-east London.

Under AMC ownership a much improved version of the Norton gearbox was developed, to be used on all the larger models of AJS, Matchless and Norton. Again, the major changes were for improved gear selection. In September 1955 a 600 cc Dominator 99 was launched. The 1946 to 1953 Long Stroke Manx Norton was 79.6 mm × 100 mm (3.1 in × 3.9 in) initially SOHC, the DOHC engine becoming available to favoured racers in 1949. The Short Stroke model (1953 to 1962) had bore and stroke of 86 mm × 85.6 mm (3.4 in × 3.4 in). It used a dry sump 499 cc single-cylinder motor, with two valves operated by bevel drive, shaft driven twin overhead camshafts. Compression ratio was 11:1. It had an Amal GP carburettor, and a Lucas racing magneto. The 1962 500 cc Manx Nortons produced 50 bhp (37 kW) at 6,780rpm, weighed 142 kg (313 lb), and had a top speed of 209 km/h (130 mph).

In 1960, a new version of the road-going Featherbed frame was developed in which the upper frame rails were bent inwards to reduce the width between the rider's knees for greater comfort. The move was also to accommodate the shorter rider as the wide frame made it difficult to reach the ground. This frame is known as the "slimline" frame; the earlier frames then became known as the "wideline".

The last Manx Nortons were sold in 1963. Even though Norton had pulled out of Grand Prix racing in 1954, the race-shop at Bracebridge Street continued until 1962, and the Manx became a mainstay of privateer racing, and even today are highly sought after, commanding high prices.

On 7 November 1960 the first new 650 cc Norton Manxman was launched for the American market only. By September 1961 the Norton 650SS appeared for the UK market, the 750 cc (Atlas). By 20 April 1962 for the American market as they demanded more power,[clarification needed] but the increases to the vertical twin engine's capacity caused a vibration problem at 5500 rpm. A 500 cc vertical twin is smoother than a single-cylinder, but if the vertical twin's capacity is enlarged vibration increases. The 750 Norton Atlas proved too expensive and costs could not be reduced. Financial problems gathered.[22]

There was an export bike primarily for use as a desert racer, sold up until 1969 as the Norton P11,[23] AJS Model 33, Matchless G15 and Norton N15 which used the Norton Atlas engine in a modified Matchless G85CS scrambler frame with AMC wheels and Teledraulic front forks. This bike was reputed to vibrate less than the Featherbed frame model. AMC singles were also sold with Norton badging in this era.[24]

Also during this period Norton developed a family of three similar smaller-capacity twin cylinder machines: first the Norton Jubilee 250 and then the Navigator 350 and the Electra 400, which had an electric starter. These models were Norton's first use of unit construction. The engine was an entirely new design by Bert Hopwood and the frame and running gear were from the Francis-Barnett range, also owned by AMC.[25]

Norton-Villiers

[edit]In 1966 AMC became insolvent and was reformed as Norton-Villiers, part of Manganese Bronze Holdings.

The 750 Norton Atlas was noted for its vibration. Rather than change engines Norton decided to change the frame, and the isolastic-framed Norton Commando 750 was the result.

In 1967 the Commando prototype was shown at the Earls Court Show in November, and introduced as a production model for 1968. Its styling, innovative isolastic frame and powerful engine made it an appealing package. The Commando easily outperformed contemporary Triumph and BSA twins and was the most powerful and best-handling British motorcycle of its day. The isolastic frame made it much smoother than the Atlas. It used rubber bushings to isolate the engine and swing arm from the frame, forks, and rider. However, as the steel-shims incorporated in the Isolastic bearings wore, often from rusting, the bike became prone to poor handling: fishtailing in high-speed turns.

The "Combat" engine was released in January 1972 with a twin roller bearing crank, 10:1 compression and developing 65 bhp (48 kW) at 6,500 rpm. Reliability immediately suffered, with frequent and early crank-shaft main-bearing failures, sometimes leading to broken crankshafts. Older engines had used one ball-bearing main bearing and one roller bearing main bearing but the Combat engine featured two roller bearings in a mistaken belief that this would strengthen the bottom-end to cope with the higher power-output. Instead the resultant crank-bending caused the rollers to "dig-in" to the races, causing rapid failure. This fragility was particularly obvious when measured against the reliability of contemporary Japanese machines.[26] This problem was solved initially by a special roller bearing of 'superblend' fame later in 1972. This was superseded by a standard high capacity roller bearing early in 1973.[27]

In April 1973 an 8.5:1 compression 828 cc "850" engine was released with German FAG SuperBlend bearings. These, featuring slightly barrel-shaped rollers, had been introduced on late model 750 cc engines to cure the Combat engine's problems of crank-flex and the consequent digging-in to the bearing-surface of the initial cylindrical bearing rollers. This model produced 51 bhp (38 kW) at 6,250 rpm but the stated power does not give a true picture of the engine performance because increased torque seemed to make up for the reduced horsepower.[28]

The Commando was offered in several different styles: the standard street model, a pseudo-scrambler with upswept pipes and the Interstate, packaged as a tourer.

Norton Villiers Triumph

[edit]

In 1972 BSA was also in financial trouble. It was given UK Government help on the condition that it merged with Norton-Villiers, and in 1973 the new Norton Villiers Triumph (NVT) was formed. The Triumph Motorcycles name came from BSA's Triumph subsidiary.

1973 saw the start of development on a new machine with a monocoque pressed steel frame, that also included a 500 cc twin, stepped piston engine[29] called the 'Wulf'. However, as the Norton Villiers Triumph company was again in serious financial problems, development of the 'Wulf' was dropped in favour of the rotary Wankel type engine inherited from BSA.

In 1974 the UK's outgoing Conservative government of Edward Heath withdrew subsidies, but the incoming Labour government of Harold Wilson restored them after the General Election. Rationalisation of the factory sites to Wolverhampton and Birmingham (BSA's Small Heath site) caused industrial disputes at Triumph's Coventry site; Triumph would go on as a workers cooperative alone. Despite mounting losses, 1974 saw the release of the 828 Roadster, Mark 2 Hi Rider, JPN Replica (John Player Norton) and Mark 2a Interstate. In 1975 the range was down to just two models: the electric start Mark 3 Interstate and the Roadster, but then the UK Government asked for a repayment of its loan and refused export credits, further damaging the company's ability to sell abroad. Production of the two models still made was ended and supplies dwindled.

Wankel engine

[edit]After the break-up of NVT, Poore established Norton Motors (1978) Ltd in the former NVT factory at Shenstone, Staffordshire to continue work on the rotary.[30] They purchased all the wankel manufacturing equipment from Hercules/DKW who had stopped manufacturing wankel machines.[31] 25 production prototypes of a dual rotor machine were built in 1979 with a planned production of 500 in 1980. However, Poore announced in December 1979 that the launch of the bike was delayed indefinitely due to the political situation surrounding the Triumph cooperative.[32][30] The company had some success making the Wankel-engined Interpol 2 motorcycle for civilian and military police forces and the RAC which was launched in 1984.[33]

In 1981 Lotus Cars planned to build a front-wheel drive (fwd) 2+2 car powered by a turbo version of the water cooled Norton wankel engine known as Project Nora. After negotiations with Norton it became apparent that the engine was not sufficiently developed for use.[34] Development of the water cooled engine continued and a water cooled prototype, the P51, was built in 1984.[30]

In a joint venture with German Norton importer Joachim "Joe" Seifert, Norton set up the German company Norton Motors (Deutschland) GmbH.[35]

After Poore's death in 1987, Manganese Bronze sold Norton to a group of investors led by Philippe LeRoux for £1.64 million, who formed Norton Group PLC.[36][37]

A civilian version of the Interpol 2 was introduced named the Classic with only 100 bikes being made.[38] Subsequent Norton Wankels were water-cooled. The Commander was launched in 1988 and was followed by the Spondon-framed F1. This model was a de-tuned replica of the Norton RCW588 factory racing machine, which won many short-distance races, but had many reliability issues requiring frequent servicing, in particular changing the primary drive chain every 100 miles.

In 1988 a new team was brought in to replace Brian Crighton's team, to try to improve the model and reduce some of its reliability issues. The team, headed by ex-Honda-team manager Barry Symmons, Honda engineer Chris Mehew and chassis specialist Ron Williams, were tasked with producing a low-cost chassis and an engine with long-term reliability. The chassis, designed by Ron Williams and made by Harris Products, was based on Yamaha's Delta box stamped panels. However, in spite of many innovative solutions from Chris Mehew, the team's was unable to improve the reliability of the engine to a commercially saleable level. They quickly realized that an engine generating 1,100 °C exhaust temperatures was not the item to place under a petrol tank.

The team's project, renamed NRS 588, did win the 1992 Isle of Man TT, ridden by Steve Hislop, North West 200, and Ulster Grand Prix races ridden by Robert Dunlop. Whilst in Northern Ireland, the team met Gordon Blair, an automotive engineer from Queen's University Belfast. Blair commented that the Japanese had abandoned development of the motorcycle variant of the Wankel engine on two main counts: 1. As the team had realised, there was just too much heat to be confined in a motorcycle chassis. 2. The pollution created by the engine burning lubrication oil and fuel was too great to meet the impending pollution regulations without a large and costly exhaust scrubbing system. In his TV Series on British industry, Sir John Harvey-Jones commented that the company was governed more by heart than head, and the racing team were the only ones worth saving.

The F1 was succeeded by the restyled and slightly less costly F1 Sport. In 2005, a group of former Norton employees were reported to have built nine F1 Sport models from existing stocks of parts.[39]

In 1996, Seifert and ex-Norton engineer Richard Negus registered Norton Motors Ltd in England.[35] The following year Seifert, on behalf of Norton Motors (Deutschland) GmbH registered the Norton trademark in some European countries[40] (Italy, Germany, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands).[41]

Aviation engines

[edit]In 1984, Teledyne Continental Motors licensed the Norton rotary technology for light aircraft engines. Norton continued to develop the engine for use in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV).[42]

In 1991, MidWest acquired the rights for light aviation use and based at Staverton Airport developed the MidWest AE series aero engine from the Norton twin-rotor engine.[43]

A David Garside led management buyout of the UAV engine part of Norton led to the formation of UAV Engines Ltd in 1992,[42] which leased part of the Shenstone site.[41]

North American ownership

[edit]Chief Executive Phillippe LeRoux attempted to diversify the company to a group with interests in property and leisure.[44] At this point the Department of Trade and Industry started to investigate improprieties in the investments of financier Philippe LeRoux and his associates[45] following which LeRoux resigned his position as Chief Executive.[46]

In a move to manage an outstanding debt of £7 million, in 1991 David MacDonald was appointed Chief Executive at the behest of the Midland Bank. McDonald sold the company to the Canadian company Wildrose Ventures in 1993 for around half a million pounds.[47][48]

Head of Wildrose Ventures Nelson Skalbania reformed the company as Norton Motors (1993) Ltd., putting his daughter Rosanda in place as General Manager at the Shenstone site.[49] The new ownership attempted to reclaim from public exhibition premises and place for auction with Sothebys ten historic motorcycles, estimated at the time to be worth £50,000,[47] including a 1904 Triumph first exhibited in 1938, which had been variously distributed to National Motor Museum, Beaulieu, Science Museum, London and Coventry Transport Museum.

This proved controversial as the museums had assumed the loans had been made on a permanent basis, and former Chief Executive David MacDonald stated "Without doubt anything which existed before 1984 does not belong to the present company. The assets were simply not transferred".[50][51]

Wildrose Ventures was ordered by the Alberta Stock Exchange to cease trading.[47][48] In 1994 ownership of the company reverted to Aquilini Investments as Skalbania was unable to repay the money he had borrowed to purchase the company. The Skalbania connection was reported as being severed by July of that year[52]

Aquilini formed Norton Motors, International, whose principal shareholder was Global Coin Corporation, an Aquilini controlled company. To hide its assets from creditors Norton was transferred to the Norton Acquisition Corporation and then to Hallmark Properties, which changed its name to Norton Motorcycles Inc. All of these were Aquilini controlled companies.[53]

Joseph Novogratz entered an agreement with Robin Herd of March Engineering to use the name March when the company was liquidated[54] and formed March Motors Limited, a UK company, in 1995. The following year the company was transferred to Minnesota.[53] The company engaged Melling Consultancy Design (MCD), run by ex-F1 engineer Al Melling, to design a range of motorcycles, the flagship model being the 1,500 cc (92 cu in) v8 Nemesis. Aquilini approached March for using the Norton name for the bikes. A joint venture was set up, Norton Motors International Inc, with all of Aquilini Norton assets, including the Shenstone factory, transferred to the new company.[55]

The new model line-up was presented at an investors meeting in London's Dorchester Hotel in December 1997 including prototypes of the 750 cc (46 cu in) four-cylinder Manx and the Nemesis. Production was due to start at Shenstone in late 1998.[55] Production was subsequently delayed and investors lost faith in the project. By November 1999 Norton Motors International were bankrupt.[54] Melling and Norton ended up in court over the Nemesis prototype.[56]

Freedom Motorcycles were developing a v-twin cruiser. In July 2002 Global Coin issued them with a licence to use the Norton trademark in North America with an option to buy the trademark for $2.5 million.[53] Freedom set up a subsidiary company Norton Motor Co.[57] The legal right of Global Coin to issue the licence was put into doubt,[53] and in March 2003 the company relinquished the right to use the Norton name in return for an undisclosed cash payment. The company changed its name to Viper Motorcycles.[58]

In the 1990s Kenny Dreer of Vintage Rebuilds of Portland, Oregon started remanufacturing Commandos with an updated specifications and capacity increased to 880cc, calling the bikes the Norton Commando VR880.[59] In 1999 Dreer received a cease and desist notice from Aquilini claiming Dreer had no right to use the names and logos of Norton and Commando on the VR880. A 4-year legal battle followed, the result of which was Dreers' company, renamed to Norton Motorsports in 2000, acquired the rights to the Norton trademarks.[60] Dreer finalised a deal with Seifert to obtain the European rights to the Norton name, giving Norton Motorsports worldwide rights to the name.[61] However the costs to obtain the trademarks put the company in a poor financial situation.[60]

The VR880 had taken the Commando to the limit of its development and donor bikes were getting more difficult to obtain. Dreer wanted to build a more modern replacement for the Commando and development of the 952 started.[60] Further development of the 952 led to the 961 and prototypes of the 961 were well received by the motorcycling press in 2006,[61] but Norton Motorsports were unable to raise the finance to put the bike into production. Dreer's investor/business partner Oliver Curme put the business up for sale in 2008.[62]

An agreement was made with Claudio Castiglioni for MV to acquire the Norton name. Designer Massimo Tamburini started work on modern Commando twin. However the deal was vetoed by the bankers Gevi SpA, who controlled 57.75% of MV.[63]

Norton Rotary Engineering Ltd had been established at Shenstone, their main business being the supplying of part and servicing of rotary Nortons. They were put up for auction in November 2003,[64] and all the parts, technical drawings and intellectual property were purchased by Norton Motors Ltd.[65] In March 2004 Norton Motors Ltd opened premises in Rugeley, Staffordshire to service the needs of rotary owners.[40]

The Donington Park revival

[edit]

After fifteen years of US ownership the Norton brand was secured by Stuart Garner, a UK businessman and owner of Norton Racing Ltd. Garner established a new 15,000 sq ft (1,400 m2) Norton factory at Donington Park to develop the Dreer-based machine.[66] The new Norton was a 961 cc (88 mm × 79 mm (3.5 in × 3.1 in)), air- and oil-cooled pushrod parallel twin with a gear-driven counterbalancer and a 270° crank (a concept pioneered on the Yamaha TRX850). The machine, a single-seat roadster styled after the earlier Commando models, has a claimed rear-wheel power output of 80 hp (60 kW), giving a top speed of over 130 mph (210 km/h).[67][68]

The new operation at Donington Park began limited production of a motorcycle based on the Kenny Dreer 961 Commando. The new motorcycle only shared the outline of the Dreer bike; all aspects of the motorcycle were re-designed in order to move into production. An updated and revised version of the rotary machine first produced in the 1980s is also being developed. The company logo was altered by "doing away with the double crossing of the 't'", in use since 1924, thereby "honouring the very first configuration of the identity, designed by [James] Norton and his daughter."[69]

In January 2011 it was announced designer Pierre Terblanche had departed Piaggio/Moto Guzzi to join Norton.[70] In August 2011 UK minister Vince Cable announced that the Government was underwriting a £7.5 million bank loan to Norton, to promote secure cash flow for their export sales. Garner responded that this finance would allow Norton to double annual production from 500 to 1,000 machines.[71]

On 29 January 2020, it was announced that the company had gone into administration.[72] Administrators BDO were appointed by Metro Bank.[73] The company had been in court over £300,000 of unpaid taxes due to HM Revenue and Customs, from an original amount of £600,000, with company representatives stating that £135,000 in "outstanding research and development tax relief" was overdue and would substantially reduce the amount owed.[74] HMRC gave the company more time to pay and the court case was adjourned until mid-February.[74] There were reports that there had been fraudulent wrongdoing which affected hundreds of pension holders who invested in the company, Norton customers, and staff; government ministers had endorsed Norton as millions of pounds of government grants and loans were provided.[75] An associated hotel business owned by Stuart Garner also went in administration and was run temporarily by an outside hotel chain.[76][77]

On 17 April 2020, it was reported that India's TVS Motor Company had acquired the business in a cash deal. In the short term, they intended to continue production of motorcycles at Donington Park using the same staff. Former CEO Stuart Garner would not be involved in the new business.[78]

In late 2021, TVS announced the opening of a new manufacturing facility at Monkspath, Solihull, to be staffed initially by 100+ workers to produce luxury hand-crafted motorcycles.[79][80]

In February 2022, former CEO Stuart Garner admitted taking circa £11 million from three pension schemes intended for employees, where Garner was the sole trustee, to invest in the business.[81] At Derby Crown Court on 31 March 2022, Garner was sentenced to eight months prison, suspended for two years.[82]

On 24 July 2023, it was announced that UK MPs were launching an inquiry into the prosecution of the pension fraud case. It was stated that the inquiry would summon key representatives from the UK's financial regulators to give evidence on the case.[83]

Donington Hall

[edit]

Norton acquired Donington Hall near the village of Castle Donington, North West Leicestershire as its new corporate headquarters in March 2013. This office and engineering facility is situated behind Donington Hall in a modern building complex, known as Hastings House. The Donington Hall site includes 26 country acres surrounded by parkland and ancient deer park.[84]

Norton Motorcycles purchased Donington Hall (formerly the headquarters of British Midland International) from British Airways for an undisclosed sum, and announced that it would vacate the current Norton factory at Donington Park, which had about 40 employees.[85] Shifting operations from Donington Park would be carried out in phases so as to not interfere with either production or distribution of Norton's bikes.[86]

TVS acquisition

[edit]On 17 April 2020 TVS motor company announced the acquisition of the brand in an all-cash deal for a reported £16 million.[87]

In December 2020, new Norton motorcycles rolled off the production line after nearly 12 months of inactivity, with interim CEO John Russell announcing “The first bikes to be built will be 40 Commandos. It's a bike people love.”[88]

In June 2021, TVS announced the appointment of Dr Robert Hentschel as chief executive officer (CEO) of Norton Motorcycles. Dr Robert Hentschel joined Norton from Valmet Automotive Holding GmbH & Co KG, where he served as managing director since 2017. Before that, he headed Ricardo Deutschland and Hentschel System and was also Director of Lotus Engineering.[89]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Terms & Conditions". 9 February 2021.

- ^ a b Holliday, Bob, Norton Story, Patrick Stephens, 1972, p.11.

- ^ a b c "Norton Motorcycle History". Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ "Norton History". Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ^ Goodley, Simon (30 January 2020). "Taken for a ride: how Norton Motorcycles collapsed amid acrimony and scandal". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ Norton sold to Indian bike firm TVS Bennetts, 18 April 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020

- ^ Project 303 Bidco Limited - overview companieshouse.gov.uk Retrieved 22 May 2020

- ^ The Motor Cycle, 10 April 1907, p292

- ^ See e.g. Holliday, Norton Story, p.17.

- ^ Woollett, Mick, Norton The Complete Illustrated History, Osprey, 1992, pp. 43, 48.

- ^ The Motor Cycle, 3 April 1919, p354

- ^ "Permits for new motor vehicles", The Motor Cycle, 16 November 1916

- ^ "A new colonial model Norton", Motor Cycle, 6 July 1916

- ^ "The Norton Programme after the War", The Motor Cycle, 28 February 1918

- ^ The Motor Cycle, 9 May 1918

- ^ The Motor, Marine and Aircraft Red Book 1917 compiled by W. C. Bersey and A. Dorey, publ. The Technical Publishing Company, p111-129

- ^ Chadwick, Ian. "Norton". Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ Smith, Robert (May–June 2011). "1936 Norton Model 18 vs. 1938 Velocette MSS". Motorcycle Classics. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Motorcycle: Norton CS1". Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ Dr G. Roe in a review of Motorcycle Chassis Design: The Theory and Practice by T. Foale and V. Willoughby in Bike Magazine, November 1984

- ^ The Victory: The Making of the New American Motorcycle (1999, Motorbooks International)

- ^ Best-Motorcycle-Gear.com Archived 7 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Norton Motorcycle History, Retrieved 23 October 2006.

- ^ "Norton P11A on Display", RealClassic.co.uk, The Cosmic Motorcycle Co. Ltd/Redleg Interactive Media, archived from the original on 27 May 2013, retrieved 25 October 2006

- ^ Ianchadwick.com, Retrieved 23 October 2006.

- ^ Sochanik, Andy (1992). "The Norton Lightweight Twins". Norton Owners Club. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ "Norton Dominator 99: Chapter Six", RealClassic.co.uk, The Cosmic Motorcycle Co. Ltd/Redleg Interactive Media, archived from the original on 27 September 2007, retrieved 23 October 2006

- ^ Heathwood, Andrew (1 March 2018). "A summary of data and information on Norton Commando main bearings" (PDF). Norton Owners Club.

- ^ NTNOA, Combat Questions & Comments, Retrieved 23 October 2006.

- ^ "Stepped Piston Engine Operating Principle". Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ a b c "Reference: NVT rotary". Classic Bike Guide. 3 August 2012.

- ^ Hege, John B. (13 August 2015). The Wankel Rotary Engine: A History. McFarland. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-7864-8658-8.

- ^ "Wankel Delay". Cycle World Magazine. December 1979. p. 25.

- ^ Scott, Gerry. "Norton Interpol 2 - Historic Police Motorcycle Group". www.policebikes.org.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Winterbottom, Oliver (17 March 2017). A Life in Car Design: Jaguar, Lotus, TVR. Veloce Publishing Ltd. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-78711-035-9.

- ^ a b "Norton F1 Sport". Real Classic. 31 August 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Cathcart, Alan (June 2020). "Norton Rotary Racers History - Rotary Race Record". Bike SA – via www.magzter.com.

- ^ Smith, Robert (15 August 2015). "Rotary-Powered Nortons: From Commander to F1". Motorcycle Classics.

- ^ Branch, Ben (5 December 2020). "The Rare Norton Classic – A Wankel Rotary-Engined British Motorcycle". Silodrome. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Café Racer magazine, No. 14, Mars-Avril, 2005, Motor Presse, p. 13

- ^ a b "About Us". Norton Motors. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Registration Statement Norton Motors International Inc". www.sec.gov. 19 June 1998. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ a b Kendall, John (October 2021). "The rotary, from bikes to aerial drones". Automotive Engineering – via www.nxtbook.com.

- ^ "Midwest-Engines Wankelmotoren". www.der-wankelmotor.de (in German). Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ "All Change", an article by Julian Ryder in Motorcycle International, March 1998, p. 2

- ^ Hotten, Russell (11 August 1992). "DTI probe into Norton looks at Rudd links (CORRECTED) - Business, News". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ^ Perkins, Kris (1991). Norton Rotaries. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-181-6.

- ^ a b c Motor Cycle News 23 February 1994 p.3 Norton 'a snip'. "Norton was sold to Canadian businessman Nelson Skalbania for just a third of its true value, claims an ex-boss of the British bike firm. David MacDonald says Norton was worth £1.42 million when Skalbania bought the company for £470,000 last year. Skalbania told the Canadian Globe and Mail newspaper: 'We did a hell of a deal'. Accessed and added 8 October 2014

- ^ a b Motor Cycle News 23 March 1994 p.5 "Museum bikes sell-off blocked." "The Alberta Stock Exchange ordered Wildrose – which paid £500,000 to take over the stricken factory late last year – to cease trading this month" Accessed and added 7 October 2014

- ^ Woollett, Mick (2004). Norton: The Complete Illustrated History. MotorBooks International. ISBN 978-0-7603-1984-0.

- ^ Motor Cycle News 23 March 1994 p.5 Museum bikes sell-off blocked. Accessed and added 7 October 2014

- ^ MacKinnon, Ian (17 March 1994). "Motorcycle sale causes dismay among the fans: Fears that historic models could disappear from view raised as new Norton owners tell museums to return machines for auction - UK, News". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- ^ Faith, Nicholas (17 July 1994). "Bunhill: Company in need of repair - Business, News". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Cieslukowski v. Norton Motors International, Civil No. 99-1056 (JRT/FLN)". Casetext. 10 September 2002. Archived from the original on 25 February 2024. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ a b "he "Norton Nemesis": Comedy or Tragedy?" (PDF). Andover Norton. November 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ a b Cameron, Kevin (January 1998). "Norton". Cycle World Magazine: 50–54.

- ^ "Norton: Lots of News, Few Bikes". American Motorcyclist. July 2003. p. 56. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Freedom Buys Rights to Norton". Brandweek. 43 (26): 11. 2002.

- ^ Groeneveld, Benno (24 March 2003). "Norton Motorcycle becomes Viper Motorcycle". www.bizjournals.com. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Hoyer, Mark (22 April 2016). "The American Era of Norton Motorcycles". Cycle World.

- ^ a b c Shinzawa, Fluto (1 August 2004). "Wheels: Master and Commando". Robb Report. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Kenny Dreer". Sound Rider. Spring 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Gardiner, Mark (23 February 2020). "Stuart Garner's not the first grifter to own Norton". Bikewriter.com. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Cathcart, Alan. "Norton Motorcycles Enters Administration. Is this the end of the road?" (7 February 2020). Cycle News. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ "Norton Factory Auction". Real Classic. 6 February 2004. Archived from the original on 6 February 2004. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "A Norton Newsflash". Real Classic. 6 February 2004. Archived from the original on 6 February 2004.

- ^ "Norton Comes Home!!!". 16 October 2008. Archived from the original on 7 December 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- ^ "Norton's next step", article by Alan Cathcart in Motorcycle Sport and Leisure, No. 585, June 2009, pp63-66

- ^ "Comeback Commando - the Norton 961" article by Alan Cathcart in Motorcycle Sport and Leisure No. 585, June 2009, pp80-83

- ^ Sinclair, Mark (8 November 2010). "A new, old logo for Norton motorcycles". Creative Review. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ "Pierre Terblanche joins Norton". Hell for Leather. Archived from the original on 16 January 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ Motorcycle News 10 August 2011

- ^ "Norton Motorcycles goes into administration". BBC News. 29 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Norton Motorcycles faces collapse as the firm enters administration Motorcycle News, 29 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020

- ^ a b Norton Motorbikes in High Court over £300,000 of unpaid taxes to HMRC Business Live 29 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020

- ^ Simon Goodley (30 January 2020). "Taken for a ride: how Norton Motorcycles collapsed amid acrimony and scandal". The Guardian.

- ^ Norton Motorcycles enters administration - what we know so far ITV News, 30 January 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020

- ^ Court repayment order - BBC

- ^ "Norton's new owners will fulfil outstanding orders". 18 April 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Norton Motorcycles opens new global HQ in Solihull business-live, 11 November 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2021

- ^ 'I am determined to make Norton big and successful' says new CEO Motorcycle News, 12 November 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2021

- ^ Norton Motorcycles: Former boss admits £11m pension breaches BBC News, 7 February 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022

- ^ Former Norton Motorcycles boss Stuart Garner walks free after £11m pension crime Derby Telegraph, 31 March 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022

- ^ Goodley, Simon (24 July 2023). "MPs launch inquiry into prosecution of Norton Motorcycles pension fraud". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ The Wire (16 March 2013). "Historic Donington Hall to serve as Norton Motorcycles New World Headquarters and Manufacturing Facilities". Cycle World. Bonnier Corp. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

Where else in the world can one tour an 18th century Gothic Revival mansion, view a Norton Motorcycle being built, watch a World Superbike race and attend an Iron Maiden concert all in the same place?

- ^ Johnson, Robin (16 March 2013). "Motorcycles move into former airline's home over at Donington Hall". Derby Telegraph. Trinity Mirror. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ Astley, Oliver (10 April 2013). "Design company revved up for the job to transform home of Norton". Derby Telegraph. Trinity Mirror. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

An 18th-century grade two-listed building presents a unique set of challenges, while the more modern Hastings House will provide a fantastic base for both motorcycle design and production.

- ^ Naqvi, Shams (25 April 2020). "A glorious Indian takeover as TVS buys Norton motorcycles". The Sunday Guardian Live. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ "Norton widen their net: Partnership with sportscar firm announced for latest dealership". www.motorcyclenews.com. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ "New Leadership Team". Norton Motorcycles. 27 October 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

External links

[edit]- Norton motorcycles

- Motorcycle manufacturers of the United Kingdom

- Manufacturing companies based in Birmingham, West Midlands

- Vehicle manufacturing companies established in 1898

- Vehicle manufacturing companies disestablished in 1996

- 1898 establishments in England

- 1996 disestablishments in England

- Defunct motorcycle manufacturers of the United Kingdom

- Re-established companies

- Vehicle manufacturing companies established in 2006

- 2006 establishments in England

- British companies established in 1898

- British companies established in 2006

- British companies disestablished in 1996

- TVS Group

- Companies that have entered administration in the United Kingdom

- Aircraft engine manufacturers of the United Kingdom