Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. | |

|---|---|

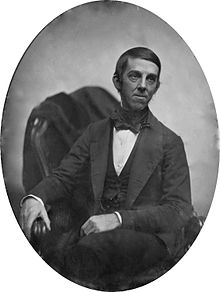

Holmes, c. 1879 | |

| Born | Oliver Wendell Holmes August 29, 1809 Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | October 7, 1894 (aged 85) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | Harvard University (AB, MD) |

| Spouse |

Amelia Lee Jackson

(m. 1840; died 1888) |

| Children | Edward Jackson Holmes Amelia Jackson Holmes Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. |

| Signature | |

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (/hoʊmz/; August 29, 1809 – October 7, 1894) was an American physician, poet, and polymath based in Boston. Grouped among the fireside poets, he was acclaimed by his peers as one of the best writers of the day. His most famous prose works are the "Breakfast-Table" series, which began with The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (1858). He was also an important medical reformer. In addition to his work as an author and poet, Holmes also served as a physician, professor, lecturer, and inventor.

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Holmes was educated at Phillips Academy and Harvard College. After graduating from Harvard in 1829, he briefly studied law before turning to the medical profession. He began writing poetry at an early age; one of his most famous works, "Old Ironsides", was published in 1830 and was influential in the eventual preservation of the USS Constitution. Following training at the prestigious medical schools of Paris, Holmes was granted his Doctor of Medicine degree from Harvard Medical School in 1836. He taught at Dartmouth Medical School before returning to teach at Harvard and, for a time, served as dean there. During his long professorship, he became an advocate for various medical reforms and notably posited the controversial idea that doctors were capable of carrying puerperal fever from patient to patient. Holmes retired from Harvard in 1882 and continued writing poetry, novels and essays until his death in 1894.

Surrounded by Boston's literary elite—which included friends such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and James Russell Lowell—Holmes made an indelible imprint on the literary world of the 19th century. Many of his works were published in The Atlantic Monthly, a magazine that he named. For his literary achievements and other accomplishments, he was awarded numerous honorary degrees from universities around the world. Holmes's writing often commemorated his native Boston area, and much of it was meant to be humorous or conversational. Some of his medical writings, notably his 1843 essay regarding the contagiousness of puerperal fever, were considered innovative for their time. He was often called upon to issue occasional poetry, or poems written specifically for an event, including many occasions at Harvard. Holmes also popularized several terms, including "Boston Brahmin" and anesthesia. He was the father of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who would become a justice on the Supreme Court of the United States.

Life and education

[edit]Early life and family

[edit]

Holmes was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on August 29, 1809. His birthplace, a house just north of Harvard Yard, was said to have been the place where the Battle of Bunker Hill was planned.[1] He was the first son of Abiel Holmes (1763–1837), minister of the First Congregational Church[2] and avid historian, and Sarah Wendell, Abiel's second wife. Sarah was the daughter of a wealthy family, and Holmes was named for his maternal grandfather, a judge.[3] The first Wendell, Evert Jansen, left the Netherlands in 1640 and settled in Albany, New York. Also through his mother, Holmes was descended from Massachusetts Governor Simon Bradstreet and his wife, Anne Bradstreet (daughter of Thomas Dudley), the first published American poet.[4]

From a young age, Holmes was small and had asthma, but he was known for his precociousness. When he was eight, he took his five-year-old brother, John, to witness the last hanging in Cambridge's Gallows Lot and was subsequently scolded by his parents.[5] He also enjoyed exploring his father's library, writing later in life that "it was very largely theological, so that I was walled in by solemn folios making the shelves bend under the load of sacred learning."[6] After being exposed to poets such as John Dryden, Alexander Pope and Oliver Goldsmith, the young Holmes began to compose and recite his own verse. His first recorded poem, which was copied down by his father, was written when he was 13.[7]

Although a talented student, the young Holmes was often admonished by his teachers for his talkative nature and habit of reading stories during school hours.[8] He studied under Dame Prentiss and William Bigelow before enrolling in what was called the "Port School", a select private academy in the Cambridgeport settlement.[9] One of his schoolmates was future critic and author Margaret Fuller, whose intellect Holmes admired.[10]

Education

[edit]Holmes's father sent him to Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, at the age of 15.[2] Abiel chose Phillips, which was known for its orthodox Calvinist teachings, because he hoped his eldest son would follow him into the ministry.[11] Holmes had no interest in becoming a theologian, however, and as a result he did not enjoy his single year at Andover. Although he achieved distinction as an elected member of the Social Fraternity, a literary club, he disliked the "bigoted, narrow-minded, uncivilized" attitudes of most of the school's teachers.[12] One teacher in particular, however, noted his young student's talent for poetry, and suggested that he pursue it. Shortly after his sixteenth birthday, Holmes was accepted by Harvard College.[13]

As a member of Harvard's class of 1829, Holmes lived at home for the first few years of his college career rather than in the dormitories. Since he measured only "five feet three inches when standing in a pair of substantial boots",[14] the young student had no interest in joining a sports team or the Harvard Washington Corps. Instead, he allied himself with the "Aristocrats" or "Puffmaniacs", a group of students who gathered in order to smoke and talk.[15] As a town student and the son of a minister, however, he was able to move between social groups.[16] He also became a friend of Charles Chauncy Emerson (brother of Ralph Waldo Emerson), who was a year older. During second year, Holmes was one of 20 students awarded the scholastic honor Deturs, which came with a copy of The Poems of James Graham, John Logan, and William Falconer. Despite his scholastic achievements, the young scholar admitted to a schoolmate from Andover that he did not "study as hard as I ought to'.[17] He did, however, excel in languages and took classes in French, Italian and Spanish.

Holmes's academic interests and hobbies were divided among law, medicine, and writing. He was elected to the Hasty Pudding, where he served as Poet and Secretary,[18] and to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society.[19] With two friends, he collaborated on a small book entitled Poetical Illustrations of the Athenaeum Gallery of Painting, which was a collection of satirical poems about the new art gallery in Boston. He was asked to provide an original work for his graduating class's commencement and wrote a "light and sarcastic" poem that met with great acclaim.[20] Following graduation, Holmes intended to go into the legal profession, so he lived at home and studied at the Harvard Law School (named Dane School at the time).[21] By January 1830, however, he was disenchanted with legal studies. "I am sick at heart of this place and almost everything connected to it", he wrote. "I know not what the temple of law may be to those who have entered it, but to me it seems very cold and cheerless about the threshold."[22]

Poetic beginnings

[edit]1830 proved to be an important year for Holmes as a poet; while disappointed by his law studies, he began writing poetry for his own amusement.[23] Before the end of the year, he had produced over fifty poems, contributing twenty-five of them (all unsigned) to The Collegian, a short-lived publication started by friends from Harvard.[24] Four of these poems would ultimately become among his best-known: "The Dorchester Giant", "Reflections of a Proud Pedestrian", "Evening / By a Tailor" and "The Height of the Ridiculous".[21] Nine more of his poems were published anonymously in the 1830 pamphlet Illustrations of the Athenaeum Gallery of Paintings.[25]

In September of that same year, Holmes read a short article in the Boston Daily Advertiser about the 18th-century frigate USS Constitution, which was to be dismantled by the Navy.[26] Holmes was moved to write "Old Ironsides" in opposition to the ship's scrapping. The patriotic poem was published in the Advertiser the very next day and was soon printed by papers in New York, Philadelphia and Washington.[27] It not only brought the author immediate national attention,[28] but the three-stanza poem also generated so much public sentiment that the historic ship was preserved, though plans to do so may have already been in motion.[29]

During the rest of the year, Holmes published only five more poems.[30] His last major poem that year was "The Last Leaf", which was inspired in part by a local man named Thomas Melvill, "the last of the cocked hats" and one of the "Indians" from the 1774 Boston Tea Party. Holmes would later write that Melvill had reminded him of "a withered leaf which has held to its stem through the storms of autumn and winter, and finds itself still clinging to its bough while the new growths of spring are bursting their buds and spreading their foliage all around it."[31] Literary critic Edgar Allan Poe called the poem one of the finest works in the English language.[32] Years later, Abraham Lincoln would also become a fan of the poem; William Herndon, Lincoln's law partner and biographer, wrote in 1867: "I have heard Lincoln recite it, praise it, laud it, and swear by it".[33]

Although he experienced early literary success, Holmes did not consider turning to a literary profession. Later he would write that he had "tasted the intoxicating pleasure of authorship" but compared such contentment to a sickness, saying: "there is no form of lead-poisoning which more rapidly and thoroughly pervades the blood and bones and marrow than that which reaches the young author through mental contact with type metal".[34]

Medical career

[edit]Medical training

[edit]Having given up on the study of law, Holmes switched to medicine. After leaving his childhood home in Cambridge during the autumn of 1830, he moved into a boardinghouse in Boston to attend the city's medical college. At that time, students studied only five subjects: medicine, anatomy and surgery, obstetrics, chemistry and materia medica.[35] Holmes became a student of James Jackson, a physician and the father of a friend, and worked part-time as a chemist in the hospital dispensary. Dismayed by the "painful and repulsive aspects" of primitive medical treatment of the time—which included practices such as bloodletting and blistering—Holmes responded favorably to his mentor's teachings, which emphasized close observation of the patient and humane approaches.[36] Despite his lack of free time, he was able to continue writing. He wrote two essays during this time which detailed life as seen from his boardinghouse's breakfast table. These essays, which would evolve into one of Holmes's most popular works, were published in November 1831 and February 1832 in The New-England Magazine under the title "The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table".[37]

In 1833, Holmes traveled to Paris to further his medical studies. Recent and radical reorganization of the city's hospital system had made medical training there highly advanced for the time.[38] At twenty-three years old, Holmes was one of the first Americans trained in the new "clinical" method being advanced at the famed École de Médecine.[39] Since the lectures were taught entirely in French, he engaged a private language tutor. Although far from home, he stayed connected to his family and friends through letters and visitors (such as Ralph Waldo Emerson). He quickly acclimated to his new surroundings. While writing to his father, he stated, "I love to talk French, to eat French, to drink French every now and then."[40]

At the hospital of La Pitié, he studied under internal pathologist Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis, who demonstrated the ineffectiveness of bloodletting, which had been a mainstay of medical practice since antiquity.[41][42] Louis was one of the fathers of the méthode expectante, a therapeutic doctrine that states the physician's role is to do everything possible to aid nature in the process of disease recovery, and to do nothing to hinder this natural process.[43] Upon his return to Boston, Holmes became one of the country's leading proponents of the méthode expectante. Holmes was awarded his Doctor of Medicine degree from Harvard in 1836; he wrote his dissertation on acute pericarditis.[44] His first collection of poetry was published later that year, but Holmes, ready to begin his medical career, wrote it off as a one-time event. In the book's introduction, he mused: "Already engaged in other duties, it has been with some effort that I have found time to adjust my own mantle; and I now willingly retire to more quiet labors, which, if less exciting, are more certain to be acknowledged as useful and received with gratitude".[45]

Medical reformer

[edit]After graduation, Holmes quickly became a fixture in the local medical scene by joining the Massachusetts Medical Society, the Boston Medical Society, and the Boston Society for Medical Improvement—an organization composed of young, Paris-trained doctors.[46] He also gained a greater reputation after winning Harvard Medical School's prestigious Boylston Prize, for which he submitted a paper on the benefits of using the stethoscope, a device with which many American doctors were not familiar.[47]

In 1837, Holmes was appointed to the Boston Dispensary, where he was shocked by the poor hygienic conditions.[48] That year he competed for and won both of the Boylston essay prizes. Wishing to concentrate on research and teaching, he, along with three of his peers, established the Tremont Medical School—which would later merge with Harvard Medical School[49]—above an apothecary shop at 35 Tremont Row in Boston. There, he lectured on pathology, taught the use of microscopes, and supervised dissections of cadavers.[50] He often criticized traditional medical practices and once quipped that if all contemporary medicine was tossed into the sea "it would be all the better for mankind—and all the worse for the fishes".[51] For the next ten years, he maintained a small and irregular private medical practice, but spent much of his time teaching. He served on the faculty of Dartmouth Medical School from 1838 to 1840,[52] where he was appointed professor of anatomy and physiology. For fourteen weeks each fall, during these years, he traveled to Hanover, New Hampshire, to lecture.[53] He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1838.[54]

After Holmes resigned his professorship at Dartmouth, he composed a series of three lectures dedicated to exposing medical fallacies, or "quackeries". Adopting a more serious tone than his previous lectures, he took great pains to reveal the false reasoning and misrepresentation of evidence that marked subjects such as "Astrology and Alchemy", his first lecture, and "Medical Delusions of the Past", his second.[55] He deemed homeopathy, the subject of his third lecture, "the pretended science" that was a "mingled mass of perverse ingenuity, of tinsel erudition, of imbecile credulity, and of artful misrepresentation, too often mingled in practice".[56] In 1842, he published the essay "Homeopathy and Its Kindred Delusions"[57] in which he again denounced the practice.

In 1846, Holmes coined the word anaesthesia. In a letter to dentist William T. G. Morton, the first practitioner to publicly demonstrate the use of ether during surgery, he wrote:

Everybody wants to have a hand in a great discovery. All I will do is to give a hint or two as to names—or the name—to be applied to the state produced and the agent. The state should, I think, be called "Anaesthesia." This signifies insensibility—more particularly ... to objects of touch.[58]

Holmes predicted his new term "will be repeated by the tongues of every civilized race of mankind."[59]

Study of childbed fever

[edit]

In 1842 Holmes attended a lecture by Walter Channing to the Boston Society for Medical Improvement about puerperal fever, or "childbed fever", a disease which at the time was a significant cause of mortality of women after delivering children. Becoming interested in the subject, Holmes spent a year going through case reports and other medical literature on the subject to ascertain the cause and possible prevention of the condition. In 1843, he presented his research to the society, which he then published as a paper "The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever" in the short-lived publication New England Quarterly Journal of Medicine and Surgery.[61] The essay argued—contrary to popular belief at the time, which predated germ theory of disease—that the cause of puerperal fever, a deadly infection contracted by women during or shortly after childbirth, stems from patient-to-patient contact via their physicians.[62] He believed that bed sheets, washcloths and articles of clothing were of particular concern in this regard.[63] Holmes gathered a large collection of evidence for this theory, including stories of doctors who had become ill and died after performing autopsies on patients who had likewise been infected.[64] In concluding his case, he insisted that a physician in whose practice even one case of puerperal fever had occurred, had a moral obligation to purify his instruments, burn the clothing he had worn while assisting in the fatal delivery, and cease obstetric practice for a period of at least six months.[65]

Though it largely escaped notice when first published, Holmes eventually came under attack by two distinguished professors of obstetrics—Hugh L. Hodge and Charles D. Meigs—who adamantly denied his theory of contagion.[66] In 1855, Holmes published a revised version of the essay in the form of a pamphlet under the new title Puerperal Fever as a Private Pestilence,[67] and discussing additional cases.[61] In a new introduction, in which Holmes directly addressed his opponents, he wrote: "I had rather rescue one mother from being poisoned by her attendant, than claim to have saved forty out of fifty patients to whom I had carried the disease."[68] He added, "I beg to be heard in behalf of the women whose lives are at stake, until some stronger voice shall plead for them."[69]

A few years later, Ignaz Semmelweis would reach similar conclusions in Vienna, where his introduction of prophylaxis (handwashing in chlorine solution before assisting at delivery) would considerably lower the puerperal mortality rate, and the then-controversial work is now considered a landmark in germ theory of disease.[28]

Teaching and lecturing

[edit]In 1847, Holmes was hired as Parkman Professor of Anatomy and Physiology at Harvard Medical School, where he served as dean until 1853 and taught until 1882.[70] Soon after his appointment, Holmes was criticized by the all-male student body for considering granting admission to a woman named Harriot Kezia Hunt.[71] Facing opposition from not only students but also university overseers and other faculty members, she was asked to withdraw her application.[72] Harvard Medical School would not admit a woman until 1945.[73] Holmes's training in Paris led him to teach his students the importance of anatomico-pathological basis of disease, and that "no doctrine of prayer or special providence is to be his excuse for not looking straight at secondary causes."[74] Students were fond of Holmes, to whom they referred as "Uncle Oliver". One teaching assistant recalled:

He enters [the classroom] and is greeted by a mighty shout and stamp of applause. Then silence, and there begins a charming hour of description, analysis, anecdote, harmless pun, which clothes the dry bones with poetic imagery, enlivens a hard and fatiguing day with humor, and brightens to the tired listener the details for difficult though interesting study.[59]

Marriage, family, and later life

[edit]On June 15, 1840, Holmes married Amelia Lee Jackson at King's Chapel in Boston.[75] She was the daughter of the Hon. Charles Jackson, formerly Associate Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and the niece of James Jackson, the physician with whom Holmes had studied.[76] Judge Jackson gave the couple a house at 8 Montgomery Place, which would be their home for eighteen years. They had three children: Civil War officer and American jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (1841–1935), Amelia Jackson Holmes (1843–1889), and Edward Jackson Holmes (1846–1884).[77]

Amelia Holmes inherited $2,000 in 1848, and she and her husband used the money to build a summer house in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Beginning in July 1849, the family spent "seven blessed summers" there.[78] Having recently given up his private medical practice, Holmes was able to socialize with other literary figures who spent time in The Berkshires; in August 1850, for example, Holmes spent time with Evert Augustus Duyckinck, Cornelius Mathews, Herman Melville, James T. Fields and Nathaniel Hawthorne.[79] Holmes enjoyed measuring the circumference of trees on his property and kept track of the data, writing that he had "a most intense, passionate fondness for trees in general, and have had several romantic attachments to certain trees in particular".[80] The high cost of maintaining their home in Pittsfield caused the Holmes family to sell it in May 1856.[78]

While serving as dean in 1850, Holmes became a witness for both the defense and prosecution during the notorious Parkman–Webster murder case.[81] Both George Parkman (the victim), a local physician and wealthy benefactor, and John Webster (the assailant) were graduates of Harvard, and Webster was professor of chemistry at the Medical School during the time of the highly publicized murder. Webster was convicted and hanged. Holmes dedicated his November 1850 introductory lecture at the Medical School to Parkman's memory.[78]

The same year, Holmes was approached by Martin Delany, an African-American man who had worked with Frederick Douglass. The 38-year-old requested admission to Harvard after having been previously rejected by four schools despite impressive credentials.[82] In a controversial move, Holmes admitted Delany and two other black men to the Medical School. Their admission sparked a student statement, which read: "Resolved That we have no objection to the education and evaluation of blacks but do decidedly remonstrate against their presence in College with us."[83] Sixty students signed the resolution, although 48 students signed another resolution which noted it would be "a far greater evil, if, in the present state of public feeling, a medical college in Boston could refuse to this unfortunate class any privileges of education, which it is in the power of the profession to bestow".[71] In response, Holmes told the black students they would not be able to continue after that semester.[83] [84] A faculty meeting directed Holmes to write that "the intermixing of races is distasteful to a large portion of the class, & injurious to the interests of the school".[71] Despite his support of education for blacks, he was not an abolitionist; against what he considered the abolitionists' habit of using "every form of language calculated to inflame", he felt that the movement was going too far.[85] This lack of support dismayed friends like James Russell Lowell, who once told Holmes he should be more outspoken against slavery. Holmes calmly responded, "Let me try to improve and please my fellowmen after my own fashion at present."[86] Nonetheless, Holmes believed that slavery could be ended peacefully and legally.[87]

Holmes lectured extensively from 1851 to 1856 on subjects such as "Medical Science as It Is or Has Been", "Lectures and Lecturing", and "English Poets of the Nineteenth Century".[88] Traveling throughout New England, he received anywhere from $40 to $100 per lecture,[89] but he also published a great deal during this time, and the British edition of his Poems sold well abroad. As social attitudes began to change, however, Holmes often found himself publicly at odds with those he called the "moral bullies"; because of mounting criticisms from the press regarding Holmes's vocal anti-abolitionism, as well as his dislike of the growing temperance movement, he chose to discontinue his lecturing and return home.[90]

Later literary success and the Civil War

[edit]In 1856, the Atlantic or Saturday Club was created to launch and support The Atlantic Monthly. This new magazine was edited by Holmes's friend James Russell Lowell, and articles were contributed by the New England literary elite such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Lothrop Motley and J. Elliot Cabot.[91] Holmes not only provided its name, but also wrote various pieces for the journal throughout the years.[70] For the magazine's first issue, Holmes produced a new version of two of his earlier essays, "The Autocrat at the Breakfast-Table". Based upon fictionalized breakfast table talk and including poetry, stories, jokes and songs,[92] the work was favored by readers and critics alike and it secured the initial success of The Atlantic Monthly.[93] The essays were collected as a book of the same name in 1858 and became his most enduring work,[94] selling ten thousand copies in three days.[95] Its sequel, The Professor at the Breakfast-Table, was released shortly after beginning in serialized installments in January 1859.[96]

Holmes's first novel, Elsie Venner, was published serially in the Atlantic beginning in December 1859.[97] Originally entitled "The Professor's Story", the novel is about a neurotic young woman whose mother was bitten by a rattlesnake while pregnant, making her daughter's personality half-woman, half-snake.[98] The novel drew a wide range of comments, including praise from John Greenleaf Whittier and condemnation from church papers, which claimed the work a product of heresy.[99]

Also in December 1859, Holmes sent medication to the ailing writer Washington Irving after visiting him at his Sunnyside home in New York; Irving died only a few months later.[100] The Massachusetts Historical Society posthumously awarded Irving an honorary membership at a tribute held on December 15, 1859. At the ceremony, Holmes presented an account of his meeting with Irving and a list of medical symptoms he had observed, despite the taboo of discussing health publicly.[101]

About 1860, Holmes invented the "American stereoscope", a 19th-century entertainment in which pictures were viewed in 3-D.[102] He later wrote an explanation for its popularity, stating: "There was not any wholly new principle involved in its construction, but, it proved so much more convenient than any hand-instrument in use, that it gradually drove them all out of the field, in great measure, at least so far as the Boston market was concerned."[103] Rather than patenting the hand stereopticon and profiting from its success, Holmes gave the idea away.[104]

Soon after South Carolina's secession from the Union in 1861 and the start of the Civil War, Holmes began publishing pieces—the first of which was the patriotic song "A Voice of the Loyal North"—in support of the Union cause. Although he had previously criticized the abolitionists, deeming them traitorous, his main concern was for the preservation of the Union.[105] In September of that year, he published an article titled "Bread and Newspapers" in the Atlantic, in which he proudly identified himself as an ardent Unionist. He wrote, "War has taught us, as nothing else could, what we can be and are" and inspiring even the upper class to have "courage ... big enough for the uniform which hangs so loosely about their slender figures."[106] However, on July 4, 1863, Holmes wrote, "how idle it is to look for any other cause than slavery as having any material agency in dividing the country" and declared it as one of "its sins against a just God".[107] Holmes also had a personal stake in the war: his oldest son, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., enlisted in the Army against his father's wishes in April 1861[108] and was injured three times in battle, including a gunshot wound in his chest at the Battle of Ball's Bluff in October 1861.[109] Holmes published in The Atlantic Monthly an account of his search for his son after hearing news of his injury at the Battle of Antietam.[110]

Amid the Civil War, Holmes's friend Henry Wadsworth Longfellow began translating Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. Beginning in 1864, Longfellow invited several friends to help at weekly meetings held on Wednesdays.[111] Holmes was part of that group, which became known as the "Dante Club"; among its members were Longfellow, Lowell, William Dean Howells, and Charles Eliot Norton.[112] The final translation was published in three volumes in the spring of 1867.[113] American novelist Matthew Pearl has fictionalized their efforts in The Dante Club (2003).[114] The same year the Dante translation was published, Holmes's second novel, The Guardian Angel, began appearing serially in the Atlantic. It was published in book form in November, though its sales were half that of Elsie Venner.[115]

Later years and death

[edit]Holmes's fame continued through his later years. The Poet at the Breakfast-Table was published in 1872.[116] Written fifteen years after The Autocrat, this work's tone was mellower and more nostalgic than its predecessor; "As people grow older," Holmes wrote, "they come at length to live so much in memory that they often think with a kind of pleasure of losing their dearest possessions. Nothing can be so perfect while we possess it as it will seem when remembered".[117] In 1876, at the age of seventy, Holmes published a biography of John Lothrop Motley, which was an extension of an earlier sketch he had written for the Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings. The following year he published a collection of his medical essays and Pages from an Old Volume of Life, a collection of various essays he had previously written for The Atlantic Monthly.[118] He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society in 1880.[119] He retired from Harvard Medical School in 1882 after thirty-five years as a professor.[120] After he gave his final lecture on November 28, the university made him professor emeritus.[121]

In 1884, Holmes published a book dedicated to the life and works of his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson. Later biographers would use Holmes's book as an outline for their own studies, but particularly useful was the section dedicated to Emerson's poetry, into which Holmes had particular insight.[122] Beginning in January 1885, Holmes's third and last novel, A Mortal Antipathy, was published serially in The Atlantic Monthly.[120] Later that year, Holmes contributed $10 to Walt Whitman, though he did not approve of his poetry, and convinced friend John Greenleaf Whittier to do the same. A friend of Whitman, a lawyer named Thomas Donaldson, had requested monetary donations from several authors to purchase a horse and buggy for Whitman who, in his old age, was becoming a shut-in.[123]

Exhausted and mourning the sudden death of his youngest son, Holmes began postponing his writing and social engagements.[124] In late 1884, he embarked on a visit to Europe with his daughter Amelia. In Great Britain he met with writers such as Henry James, George du Maurier and Alfred Tennyson, and was awarded a Doctor of Letters degree from the University of Cambridge, a Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Edinburgh, and a third honorary degree from the University of Oxford.[125] Holmes and Amelia then visited Paris, a place that had significantly influenced him in his earlier years. He met with chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur, whose previous studies in germ theory had helped reduce the mortality rate of women who had puerperal fever. Holmes called Pasteur "one of the truest benefactors of his race".[126] After returning to the United States, Holmes published a travelogue, Our One Hundred Days in Europe.[127]

In June 1886, Holmes received an honorary degree from Yale University Law School.[128] His wife of more than forty years, who had struggled with an illness that had kept her an invalid for months, died on February 6, 1888.[129] The younger Amelia died the following year after a brief malady. Despite his weakening eyesight and a fear that he was becoming antiquated, Holmes continued to find solace in writing. He published Over the Teacups, the last of his table-talk books, in 1891.[130]

Towards the end of his life, Holmes noted that he had outlived most of his friends, including Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. As he said, "I feel like my own survivor ... We were on deck together as we began the voyage of life ... Then the craft which held us began going to pieces."[131] His last public appearance was at a reception for the National Education Association in Boston on February 23, 1893, where he presented the poem "To the Teachers of America".[132] A month later, Holmes wrote to Harvard president Charles William Eliot that the university should consider adopting the honorary doctor of letters degree and offer one to Samuel Francis Smith, though one was never issued.[133]

Holmes died quietly after falling asleep in the afternoon of Sunday, October 7, 1894.[134] As his son Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote, "His death was as peaceful as one could wish for those one loves. He simply ceased to breathe."[135] Holmes's memorial service was held at King's Chapel and overseen by Edward Everett Hale. Holmes was buried alongside his wife in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[136]

Writing

[edit]Poetry

[edit]Holmes is one of the fireside poets, together with William Cullen Bryant, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, and John Greenleaf Whittier.[137] These poets—whose writing was characterized as family-friendly and conventional—were among the first Americans to build substantial popularity in Europe. Holmes in particular believed poetry had "the power of transfiguring the experiences and shows of life into an aspect which comes from the imagination and kindles that of others".[33]

Due to his immense popularity during his lifetime, Holmes was often called upon to produce commemorative poetry for specific occasions, including memorials, anniversaries and birthdays. Referring to this demand for his attention, he once wrote that he was "a florist in verse, and what would people say / If I came to a banquet without my bouquet?"[138] As critic Hyatt Waggoner noted, however, "very little ... survives the occasions that produced it".[139] Holmes became known as a poet who expressed the benefits of loyalty and trust at serious gatherings, as well as one who showed wit at festivities and celebrations. Edwin Percy Whipple for one considered Holmes to be "a poet of sentiment and passion. Those who know him only as a comic lyricist, as the libellous laureate of chirping follow and presumptuous egotism, would be surprised at the clear sweetness and skylark thrill of his serious and sentimental compositions".[140]

In addition to the commemorative nature of much of Holmes's poetry, some pieces were written based on his observations of the world around him. This is the case with two of Holmes's best known and critically successful poems—"Old Ironsides" and "The Last Leaf"—which were published when he was a young adult.[141] As is seen with poems such as "The Chambered Nautilus" and "The Deacon's Masterpiece or The Wonderful One-Hoss Shay", Holmes successfully concentrated his verse upon concrete objects with which he was long familiar, or had studied at length, such as the one-horse shay or a seashell.[142] Some of his works also deal with his personal or family history; for example, the poem "Dorothy Q" is a portrait of his maternal great-grandmother. The poem combines pride, humor and tenderness in short rhyming couplets:[143]

O Damsel Dorothy! Dorothy Q.!

Strange is the gift that I owe to you;

Such a gift as never a king

Save to daughter or son might bring,—

All my tenure of heart and hand,

All my title to house and land;

Mother and sister and child and wife

And joy and sorrow and death and life![144]

Holmes, an outspoken critic of over-sentimental Transcendentalist and Romantic poetry, often slipped into sentimentality when writing his occasional poetry, but would often balance such emotional excess with humor.[145] Critic George Warren Arms believed Holmes's poetry to be provincial in nature, noting his "New England homeliness" and "Puritan familiarity with household detail" as proof.[146] In his poetry, Holmes often connected the theme of nature to human relations and social teachings; poems such as "The Ploughman" and "The New Eden", which were delivered in commemoration of Pittsfield's scenic countryside, were even quoted in the 1863 edition of the Old Farmer's Almanac.[147]

He composed several hymn texts, including Thou Gracious God, Whose Mercy Lends and Lord of All Being, Throned Afar.[148]

Prose

[edit]Although mainly known as a poet, Holmes wrote numerous medical treatises, essays, novels, memoirs and table-talk books.[149] His prose works include topics that range from medicine to theology, psychology, society, democracy, sex and gender, and the natural world.[150] Author and critic William Dean Howells argued that Holmes created a genre called dramatized (or discursive) essay, in which major themes are informed by the story's plot,[151] but his works often use a combination of genres; excerpts of poetry, essays and conversations are often included throughout his prose.[152] Critic William Lawrence Schroeder described Holmes's prose style as "attractive" in that it "made no great demand on the attention of the reader." He further stated that although the author's earlier works (The Autocrat and The Professor of the Breakfast-Table) are "virile and fascinating", later ones such as Our Hundred Days in Europe and Over the Teacups "have little distinction of style to recommend them."[153]

Holmes first gained international fame with his "Breakfast-Tables" series.[154] These three table-talk books attracted a diverse audience due to their conversational style, which made readers feel an intimate connection to the author, and resulted in a flood of letters from admirers.[155] The series' conversational tone is not only meant to mimic the philosophical debates and pleasantries that occur around the breakfast table, but it is also used in order to facilitate an openness of thought and expression.[156] As the Autocrat, Holmes states in the first volume:

This business of conversation is a very serious matter. There are men that it weakens one to talk with an hour more than a day's fasting would do. Mark this that I am going to say, for it is as good as a working professional man's advice, and costs you nothing: It is better to lose a pint of blood from your veins than to have a nerve tapped. Nobody measures your nervous force as it runs away, nor bandages your brain and marrow after the operation.[157]

The various speakers represent different facets of Holmes's life and experiences. The speaker of the first installment, for example, is understood to be a doctor who spent several years studying in Paris, while the second volume—The Professor at the Breakfast-Table—is told from the point of view of a professor of a distinguished medical school.[158] Although the speakers discuss myriad topics, the flow of conversation always leads to supporting Holmes's Paris-taught conception of science and medicine and how they relate to morality and the mind.[159] Autocrat in particular addresses philosophical issues such as the nature of one's self, language, life and truth.[160]

Holmes wrote in the second preface to Elsie Venner, his first novel, that his aim in writing the work was "to test the doctrine of 'original sin' and human responsibility for the distorted violation coming under that technical denomination".[161] He also stated his belief that "a grave scientific doctrine may be detected lying beneath some of the delineations of character" throughout all fiction.[162] Deeming the work a "psychological romance", he employed a romantic narrative in order to describe moral theology from a scientific perspective. This means of expression is also present in his two other novels, in which Holmes uses medical or psychological dilemmas to further the story's dramatic plot.[163]

Holmes referred to his novels as "medicated novels".[164] Some critics believe that these works were innovative in exploring theories of Sigmund Freud and other emerging psychiatrists and psychologists.[165] The Guardian Angel, for example, explores mental health and repressed memory, and Holmes uses the concept of the unconscious mind throughout his works.[165] A Mortal Antipathy depicts a character whose phobias are rooted in psychic trauma, later cured by shock therapy.[166] Holmes's novels were not critically successful during his lifetime. As psychiatrist Clarence P. Oberndorf, author of The Psychiatric Novels of Oliver Wendell Holmes, states, the three works are "poor fiction when judged by modern criteria. ... Their plots are simple, almost juvenile and, in two of them, the reader is not disappointed in the customary thwarting of the villain and the coming of true love to its own".[167]

Legacy and criticism

[edit]

Holmes was well respected by his peers, and garnered a large, international following throughout his long life. Particularly noted for his intelligence, he was named by American theologian Henry James Sr. "intellectually the most alive man I ever knew".[134] Critic John G. Palfrey also praised Holmes, referring to him as "a man of genius ... His manner is entirely his own, manly and unaffected; generally easy and playful, and sinking at times into 'a most humorous sadness'".[168] On the other hand, critics S. I. Hayakawa and Howard Mumford Jones argued that Holmes was "distinctly an amateur in letters. His literary writings, on the whole, are partly the leisure-born meditations of a physician, partly a means of spreading certain items of professional propaganda, partly a distillation of his social life."[169]

Like Samuel Johnson in 18th-century England, Holmes was noted for his conversational powers in both his life and literary output.[170] Though he was popular at the national level, Holmes promoted Boston culture and often wrote from a Boston-centric point of view, believing the city was "the thinking centre of the continent, and therefore of the planet".[82] He is often referred to as a Boston Brahmin, a term that he created while referring to the oldest families in the Boston area.[171] The term, as he used it, referred not only to members of a good family but also implied intellectualism.[28] He also famously nicknamed Emerson's The American Scholar the American "intellectual Declaration of Independence".[172]

Although his essay on puerperal fever has been deemed "the most important contribution made in America to the advancement of medicine" up to that time,[69] Holmes is most famous as a humorist and poet. Editor and critic George Ripley, an admirer of Holmes, referred to him as "one of the wittiest and most original of modern poets".[173] Emerson noted that, though Holmes did not renew his focus on poetry until later in his life, he quickly perfected his role "like old pear trees which have done nothing for ten years, and at last begin to grow great."[92]

Poems by Holmes, along with those by the other fireside or schoolroom poets, were often required to be memorized by schoolchildren. Although learning by rote recitation began fading out by the 1890s, these poets nevertheless remained fixed as ideal New England poets.[174] Literary scholar Lawrence Buell wrote of these poets: "we value [them] less than the nineteenth century did but still regard as the mainstream of nineteenth-century New England verse."[175] Many of these poets soon became recognized only as children's poets, as noted by a 20th-century scholar who asked about Holmes's contemporary Longfellow: "Who, except wretched schoolchildren, now reads Longfellow?"[176] Another modern scholar notes that "Holmes is a casualty of the ongoing movement to revise the literary canon. His work is the least likely of the Fireside Poets to find its way into American literature anthologies."[177]

The school library of Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, where Holmes studied as a child, is named the Oliver Wendell Holmes Library, or the OWHL, in his memory. Items from Holmes's personal library—including medical papers, essays, songs and poems—are held in the library's Special Collections department.[178] In 1915, Bostonians placed a memorial seat and sundial behind Holmes's final home at 296 Beacon Street in a spot where he would have seen it from his library.[179] King's Chapel in Boston, where Holmes worshiped, erected an inscribed memorial tablet in his honor.[135] The tablet notes Holmes's achievements in the order he recognized them: "Teacher of Anatomy, Essayist and Poet". It ends with a quote from Horace's Ars Poetica: Miscuit Utile Dulci: "He mingled the useful with the pleasant."[134]

Selected list of works

[edit]- Poetry

- Poems (1836)[180]

- Songs in Many Keys (1862)

- Medical and psychological studies

- Puerperal Fever as a Private Pestilence (1855)

- Mechanism in Thought and Morals (1871)

- Table-talk books

- The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (1858)[180]

- The Professor at the Breakfast-Table (1860)[180]

- The Poet at the Breakfast-Table (1872)[180]

- Over the Teacups (1891)[116]

- Novels

- Elsie Venner (1861)[180]

- The Guardian Angel (1867)[180]

- A Mortal Antipathy (1885)[180]

- Articles

- "The Stereoscope and the Stereograph", The Atlantic Monthly, volume 6 (1859)

- "Sun-painting and sun-sculpture", The Atlantic Monthly, volume 8 (July 1861)

- "Doings of the sun-beam", The Atlantic Monthly, volume 12 (July 1863)

- Biographies and travelogue

- John Lothrop Motley, A Memoir (1876)

- Ralph Waldo Emerson (1884)

- Our Hundred Days in Europe (1887)[180]

See also

[edit]- Epeolatry, a term coined by Holmes

- George Livermore, a childhood classmate

- Wendell, North Carolina, a town named after Holmes

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sullivan, 226

- ^ a b Novick, 3

- ^ Small, 23

- ^ Small, 20

- ^ Small, 24

- ^ Tilton, 6

- ^ Tilton, 8

- ^ Tilton, 23

- ^ Hoyt, 21

- ^ Tilton, 24

- ^ Hoyt, 24

- ^ Hoyt, 27–28

- ^ Hoyt, 28

- ^ Tilton, 50

- ^ Tilton, 36

- ^ Hoyt, 32

- ^ Tilton, 37

- ^ Catalogue of the Officers and Members of the Hasty-Pudding Club in Harvard University. Cambridge, MA: Metcalf and Company, 1846: 48.

- ^ Hoyt, 35

- ^ Hoyt, 37

- ^ a b Small, 34

- ^ Sullivan, 231

- ^ Hoyt, 38

- ^ Tilton, 62–63

- ^ Hoyt, 63

- ^ Novick, 4

- ^ Hoyt, 42

- ^ a b c Menand, 6

- ^ Wilson, Susan. Boston Sights and Insights: An Essential Guide to Historic Landmarks In and Around Boston. Boston: Beacon Press, 2003: 54–55. ISBN 0-8070-7135-8

- ^ Tilton, 65

- ^ Holmes, Complete Poetical Works, 4

- ^ Hoyt, 45

- ^ a b Small, 37

- ^ Tilton, 67

- ^ Hoyt, 47

- ^ Small, 38

- ^ Hoyt, 48

- ^ Dowling, 7

- ^ Gibian, 2

- ^ Hoyt, 52

- ^ Louis' findings on the subject were published as Recherches sur les effets de la saignée dan quelques maladies inflammatoires, et sur l'action de l'émétique et des vésicatoires dans la pneumonie. Paris: J-B Ballière, 1835.

- ^ Dowling, 29

- ^ Dowling, 43

- ^ Small, 44

- ^ Hoyt, 138

- ^ Hoyt, 72

- ^ Hoyt, 80–81

- ^ Hoyt, 86

- ^ Tilton, 149

- ^ Novick, 6

- ^ Sullivan, 233

- ^ Blough, Barbara; Dana Cook Grossman. "Two Hundred Years of Medicine at Dartmouth". Dartmouth Medical School. Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ^ Small, 48

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter A" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Tilton, 166

- ^ Small, 50

- ^ Holmes, Oliver Wendell. Homœopathy, and its Kindred Delusions; two lectures delivered before the Boston society for the diffusion of useful knowledge. Boston: William D. Ticknor, 1842.

- ^ Small, 55

- ^ a b Sullivan, 235

- ^ Meigs, Charles Delucena. On the Nature, Signs, and Treatment of Childbed Fevers. Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lea, 1854: 104.

- ^ a b Shaikh, Safiya, ""The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever" (1843), by Oliver Wendell Holmes", Embryo Project Encyclopedia, Arizona State University, School of Life Sciences, July 26, 2017. ISSN 1940-5030. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Small, 52

- ^ Shell, Hanna Rose (2020). Shoddy: From Devil's Dust to the Renaissance of Rags. Chicago: University of Chicago. pp. 15, 80–81. ISBN 9780226377759.

- ^ Hoyt, 106–107

- ^ Hoyt, 107

- ^ Dowling, 93

- ^ Holmes, Oliver Wendell, Puerperal Fever as a Private Pestilence, Ticknor and Fields, Boston, 1955.

- ^ Tilton, 175

- ^ a b Sullivan, 234

- ^ a b Broaddus, 46

- ^ a b c Menand, 8

- ^ Gibian, 176

- ^ Menand, 9

- ^ Dowling, xxi

- ^ Novick, 7

- ^ Small, 49

- ^ Small, 49–50

- ^ a b c Small, 66

- ^ Miller, Edwin Haviland. Salem Is My Dwelling Place: A Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991:307–308. ISBN 0-87745-381-0.

- ^ Small, 67

- ^ Hoyt, 135

- ^ a b Menand, 7

- ^ a b Broaddus, 94

- ^ "The Major Findings of Harvard's Report on Its Ties to Slavery". The New York Times. April 26, 2022.

- ^ Hoyt, 144

- ^ Sullivan, 241

- ^ Novick, 15

- ^ Small, 70

- ^ Hoyt, 153

- ^ Hoyt, 161

- ^ Hoyt, 167

- ^ a b Novick, 19

- ^ Tilton, 236

- ^ Sullivan, 237

- ^ Hoyt, 193

- ^ Small, 100

- ^ Broaddus, 62

- ^ Hoyt, 188

- ^ Small, 122

- ^ Jones, Brian Jay. Washington Irving: An American Original. New York: Arcane Publishing, 2008: 402. ISBN 978-1-55970-836-4

- ^ Small, 133

- ^ Tilton, 425

- ^ Holmes, Oliver Wendell (March 1952). "The American Stereoscope" (PDF). Image: Journal of Photography of the George Eastman House. 1 (3). Rochester, NY. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ Hoyt, 201

- ^ Small, 76–77

- ^ Broaddus, 110

- ^ Holmes, Oliver Wendell. "The Inevitable Trial" in Pages from an Old Volume of Life. Boston, 1883: 85,87.

- ^ Novick, 34–35

- ^ White, G. Edward. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006: 19–20. ISBN 978-0-19-530536-4

- ^ Holmes, Oliver Wendell (December 1862). "My Hunt After the Captain". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- ^ Arvin, Newton. Longfellow: His Life and Work. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1963: 140.

- ^ Calhoun, Charles C. Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004: 236. ISBN 0-8070-7026-2.

- ^ Irmscher, Christoph. Longfellow Redux. University of Illinois, 2006: 263. ISBN 978-0-252-03063-5.

- ^ Calhoun, Charles C. Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004: 258. ISBN 0-8070-7026-2.

- ^ Small, 123

- ^ a b Westbrook, Perry D. A Literary History of New England. Philadelphia: Lehigh University Press, 1988: 181. ISBN 978-0-934223-02-7

- ^ Hoyt, 237

- ^ Hoyt, 251

- ^ "APS Member History".

- ^ a b Small, 128

- ^ Hoyt, 252

- ^ Hoyt, 258

- ^ Kaplan, Justin. Walt Whitman: A Life. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980: 25. ISBN 0-671-22542-1

- ^ Hoyt, 261

- ^ Hoyt, 264

- ^ Hoyt, 266–267

- ^ Hoyt, 269

- ^ Novick, 181

- ^ Novick, 183

- ^ Hoyt, 273–274

- ^ Sullivan, 225

- ^ Small, 150

- ^ Small, 75–76

- ^ a b c Sullivan, 242

- ^ a b Small, 153

- ^ Novick, 200

- ^ Heymann, C. David. American Aristocracy: The Lives and Times of James Russell, Amy, and Robert Lowell. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1980: 91. ISBN 0-396-07608-4

- ^ Kennedy, 271

- ^ Sullivan, 238

- ^ Small, 73

- ^ Small, 36–37

- ^ Small, 96

- ^ Small, 110–111

- ^ Holmes, Complete Poetical Works, 187, ll. 33–40

- ^ Arms, 99

- ^ Arms, 101

- ^ Small, 68

- ^ Duncan Campbell (1908). Hymns and Hymn Makers. A. &. C. Black. p. 170.

- ^ Weinstein, 1

- ^ Weinstein, 2

- ^ Weinstein, 48

- ^ Weinstein, 2–3

- ^ Schroeder, 51

- ^ Novick, 20

- ^ Gibian, 68

- ^ Weinstein, 29

- ^ Holmes, Oliver Wendell. The Autocrat at the Breakfast-Table. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1916: 7

- ^ Dowling, 110

- ^ Dowling, 111–112

- ^ Weinstein, 27

- ^ Weinstein, 67

- ^ Hoyt, 189

- ^ Weinstein, 68

- ^ Gibian, 4

- ^ a b Weinstein, 94

- ^ Small, 130–131

- ^ Oberndorf, Clarence P. The Psychiatric Novels of Oliver Wendell Holmes. Revised ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 1946: 13–14

- ^ Knight, 199

- ^ Weinstein, 6

- ^ Dowling, 113

- ^ Watson, Peter. Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud. New York: Harper Perennial, 2005: 688. ISBN 978-0-06-093564-1

- ^ Sullivan, 235–236

- ^ Crowe, Charles. George Ripley: Transcendentalist and Utopian Socialist. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1967: 247.

- ^ Sorby, Angela. Schoolroom Poets: Childhood, Performance, and the Place of American Poetry, 1865–1917. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire Press, 2005: 133. ISBN 1-58465-458-9

- ^ Buell, Lawrence. New England Literary Culture: From Revolution Through Renaissance. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986: 43. ISBN 0-521-37801-X

- ^ Arvin, Newton. Longfellow: His Life and Work. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1963: 321.

- ^ Knight, 200

- ^ "Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes OWH Library at Phillips Academy Andover". Oliver Wendell Holmes Library. Retrieved May 6, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Corbett, William. Literary New England: A History and Guide. Boston: Faber and Faber, 1993: 76. ISBN 0-571-19816-3

- ^ a b c d e f g h Knight, 198

References

[edit]- Arms, George Warren. The Fields Were Green: A New View of Bryant, Whittier, Holmes, Lowell, and Longfellow. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1953. OCLC 270214.

- Broaddus, Dorothy C. Genteel Rhetoric: Writing High Culture in Nineteenth-Century Boston. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina, 1999. ISBN 1-57003-244-0.

- Dowling, William C. Oliver Wendell Holmes in Paris: Medicine, Theology, and The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table. Hanover: University Press of New England, 2006. ISBN 1-58465-579-8.

- Gibian, Peter. Oliver Wendell Holmes and the Culture of Conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-511-01763-4.

- Holmes, Oliver Wendell. The Complete Poetical Works of Oliver Wendell Holmes. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1908. OCLC 192211.

- Hoyt, Edwin Palmer. The Improper Bostonian: Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes. New York: Morrow, 1979. ISBN 0-688-03429-2.

- Kennedy, William Sloane. Oliver Wendell Holmes: Poet, Littérateur, Scientist. Boston: S.E. Cassino, 1883. OCLC 11173078.

- Knight, Denise D. "Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809–1894)", Writers of the American Renaissance: An A-to-Z Guide. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003. ISBN 0-313-32140-X.

- Menand, Louis. The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001. ISBN 0-374-19963-9.

- Morse, John Torrey (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 616–617.

- Novick, Sheldon M. Honorable Justice: The Life of Oliver Wendell Holmes. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1989. ISBN 0-316-61325-8.

- Schroeder, William Lawrence. Oliver Wendell Holmes: An Appreciation. London: Philip Green, 1909. OCLC 11877015.

- Small, Miriam Rossiter. Oliver Wendell Holmes. Twayne's United States authors series, 29. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1962. OCLC 273508.

- Sullivan, Wilson. New England Men of Letters. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1972. ISBN 0-02-788680-8.

- Tilton, Eleanor M. Amiable Autocrat: A Biography of Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes. New York: H. Schuman, 1947. OCLC 14671680.

- Weinstein, Michael A. The Imaginative Prose of Oliver Wendell Holmes. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006. ISBN 0-8262-1644-7.

External links

[edit]Sources

- Stephen, Leslie (1898). . Studies of a Biographer. Vol. 2. London: Duckworth and Co.

- Works by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. at the Internet Archive

- Works by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Oliver Wendell Holmes Library, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

- Oliver Wendell Holmes letters. Available online through Lehigh University's I Remain: A Digital Archive of Letters, Manuscripts, and Ephemera.

Other

- The name of Sherlock Holmes – Dr. Holmes

- Quotes by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

- "The Annotated Autocrat" a mostly complete set of annotations to Holmes's Autocrat of the Breakfast Table

- "The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever" by Holmes

- The Deacon's Masterpiece The Wonderful One-Hoss Shay: A Logical Story – audio reading

- Works with text by Holmes, Oliver Wendell

- 1809 births

- 1894 deaths

- 19th-century American novelists

- 19th-century American poets

- American essayists

- American expatriates in France

- American people of Dutch descent

- American people of English descent

- 19th-century American physicians

- American medical writers

- Arthur Conan Doyle

- Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Geisel School of Medicine faculty

- Harvard Medical School alumni

- Writers from Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Phillips Academy alumni

- Novelists from Massachusetts

- Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

- Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees

- American male novelists

- American male essayists

- American male poets

- Hasty Pudding alumni

- Harvard College alumni

- People from Beacon Hill, Boston

- Occasional poets

- Sherlock Holmes