Pā

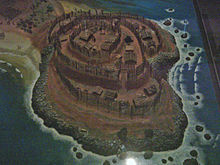

The word pā (Māori pronunciation: [ˈpaː]; often spelled pa in English) can refer to any Māori village or defensive settlement, but often refers to hillforts – fortified settlements with palisades and defensive terraces – and also to fortified villages. Pā sites occur mainly in the North Island of New Zealand, north of Lake Taupō. Over 5,000 sites have been located, photographed and examined, although few have been subject to detailed analysis. No pā have been yet located from the early colonization period when early Polynesian-Māori colonizers lived in the lower South Island. Variations similar to pā occur throughout central Polynesia, in the islands of Fiji, Tonga and the Marquesas Islands.

In Māori culture, a great pā represented the mana (prestige or power) and strategic ability of an iwi (tribe or tribal confederacy), as personified by a rangatira (chieftain). Māori built pā in various defensible locations around the territory (rohe) of an iwi to protect fertile plantation-sites and food supplies.

Description

[edit]Almost all pā were constructed on prominent raised ground, especially on volcanic hills. The natural slope of the hill is then terraced. Dormant volcanoes were commonly used for pā in the area of present-day Auckland. Pā are multipurpose in function. Pā that have been extensively studied after the New Zealand Wars and more recently were found to safeguard food- and water-storage sites or wells, food-storage pits (especially for kūmara),[1] and small integrated plantations, maintained inside the pā.

Recent studies have shown that in most cases, few people lived long-term in a single pā, and that iwi maintained several pā at once, often under the control of a hapū (subtribe). Early European scholarly research on pā typically considered pā as isolated points settlements, analogous to European towns. Typically pā were a part of a greater area of seasonal occupation.[2] The area in between pā were primarily common residential and horticultural sites. Over time, some pā may have become more important as places of display and as a symbol of status (tohu rangatira), rather than purely defensive locations.[3][2]

Traditional designs

[edit]

Traditional pā took a variety of designs. The simplest pā, the tuwatawata, generally consisted of a single wood palisade around the village stronghold, and several elevated stage levels from which to defend and attack. A pā maioro, general construction used multiple ramparts, earthen ditches used as hiding posts for ambush, and multiple rows of palisades. The most sophisticated pā was called a pā whakino, which generally included all the other features plus more food storage areas, water wells, more terraces, ramparts, palisades, fighting stages, outpost stages, underground dug-posts, mountain or hill summit areas called "tihi", defended by more multiple wall palisades with underground communication passages, escape passages, elaborate traditionally carved entrance ways, and artistically carved main posts.

An important feature of pā that set them apart from British forts was their incorporation of food storage pits; some pā were built exclusively to safely store food. Pā locations include volcanoes, spurs, headlands, ridges, peninsulas and small islands, including artificial islands.

Standard features included a community well for long-term supply of water, designated waste areas, an outpost or an elevated stage on a summit on which a pahu would be slung on a frame that when struck would alarm the residents of an attack. The pahu was a large oblong piece of wood with a groove in the middle. A heavy piece of wood was struck from side to side of the groove to sound the alarm.[4] The whare (a Māori dwelling place or hut) of the rangatira and ariki (chiefs) were often built on the summit with a weapons storage. In the 17th and 18th centuries the taiaha was the most common weapon. The chief's stronghold on the summit could be bigger than a normal whare, some measuring 4.5 meters x 4 meters.

Artefacts

[edit]Pā excavated in Northland have provided numerous clues to Māori tool and weapon manufacturing, including the manufacturing of obsidian (volcanic glass), chert and argillite basalt, flakes, pounamu chisels, adzes, bone and ivory weapons, and an abundance of various hammer tools which had accumulated over hundreds of years.

Chert, a fine-grained, easily worked stone, familiar to Māori from its extensive use in Polynesia, was the most commonly used stone, with thousands of pieces being found in some Northland digs. Chips or flakes of chert were used as drills for pā construction, and for the making process of other industrial tools like Polynesian fish hooks. Another find in Northland pā studies was the use of what Māori call "kokowai", or red ochre, a red dye made from red iron or aluminium oxides, which is finely ground, then mixed with an oily substance like fish oil or a plant resin. Māori used the chemical compound to keep insects away in pā built in more hazardous platforms in war. The compound is still widely used on whare and waka, and is used as a coating to prevent the wood from drying out.

Storage

[edit]Pā studies showed that on lower pā terraces were semi-underground whare (huts) about 2.4 m x 2 m for housing kūmara. These houses or storage houses were equipped with wide racks to hold hand-woven kūmara baskets at an angle of about 20 degrees, to shed water.

These storage whare had internal drains to drain water.[5] In many pā studies, kūmara were stored in rua (kūmara pits). Common or lower rank Māori whare were on the lower or outer land, sometimes partly sunk into the ground by 30–40 cm. On the lower terraces, the ngutu (entrance gate) is situated. It had a low fence to force attackers to slow and take an awkward high step. The entrance was usually overlooked by a raised stage so attackers were very vulnerable.

Most food was grown outside the pā, though in some higher ranked pā designs there were small terraces areas to grow food within the palisades. Guards were stationed on the summit during times of threat. The blowing of a polished shell trumpet or banging a large wooden gong signaled the alarm. In some pā in rocky terrain, boulders were used as weapons. Some iwi such as Ngāi Tūhoe did not construct pā during early periods, but used forest locations for defence, attack and refuge – called pā runanga.[citation needed] Leading British archaeologist, Lady Aileen Fox (1976) has stated that there were about 2,000 hillforts in Britain and that New Zealand had twice that number but further work since then has raised the number of known pā to over 5,000.[citation needed]

Pā played a significant role in the New Zealand Wars. They are also known from earlier periods of Māori history from around 500 years ago, suggesting that Māori iwi ranking and the acquiring of resources and territory began to bring about warfare and led to an era of pā evolution.[6][7]

Fortification

[edit]

Their main defence was the use of earth ramparts (or terraced hillsides), topped with stakes or wicker barriers. The historically later versions were constructed by people who were fighting with muskets and melee weapons (such as spears, taiaha and mere) against the British Army and armed constables, who were equipped with swords, rifles, and heavy artillery such as howitzers[8] and rocket artillery.

Simpler gunfighter pā of the post contact period could be put in place in very limited time scales, sometimes two to fifteen days, but the more complex classic constructions took months of hard labour, and were often rebuilt and improved over many years. The normal methods of attacking a classic pā were firstly the surprise attack at night when defences were not routinely manned. The second was the siege which involved less fighting and results depended on who had the better food resources. The third was to use a device called a Rou – a half-metre length of strong wood attached to a stout length of rope made from raupō leaves. The Rou was slipped over the palisade and then pulled by a team of toa until the wall fell. Gunfighter pā could resist bombardment for days with limited casualties although the psychological impact of shelling usually drove out defenders if attackers were patient and had enough ammunition. Some historians have wrongly credited Māori with inventing trench warfare with its associated variety of earth works for protection.[9] Serious military earth works were first recorded in use by French military engineers in the 1700s and were used extensively at Crimea and in the US Civil War.[citation needed] Māori's undoubted skill at constructing earthworks evolved from their skill at building traditional pā which, by the late 18th century, involved considerable earthworks to create rua (food storage pits), ditches, earth ramparts and multiple terraces.

Gunfighter pā

[edit]Warrior chiefs like Te Ruki Kawiti realised that these properties were a good counter to the greater firepower of the British. With that in mind, they sometimes built pā purposefully as a defensive fortification, like at Ruapekapeka, a new pā constructed specifically to draw the British away, instead of protecting a specific site or place of habitation like more traditional classic pā.[10] At the Battle of Ruapekapeka the British suffered 45 casualties against only 30 amongst the Māori. The British learned from earlier mistakes and listened to their Māori allies. The pā was subjected to two weeks of bombardment before being successfully attacked. Hōne Heke won the battle and "he carried his point", with the Crown never tried to resurrect the flagstaff at Kororareka while Kawiti lived.[11] Afterwards, British engineers twice surveyed the fortifications, produced a scale model and tabled the plans in the House of Commons.[12]

The fortifications of such a purpose-built pā included palisades of hard pūriri trunks sunk about 1.5m in the ground and split timber, with bundles of protective flax padding in the later gunfighter pā, the two lines of palisade covering a firing trench with individual pits, while more defenders could use the second palisade to fire over the heads of the first below. Simple communication trenches or tunnels were also built to connect the various parts, as found at Ohaeawai Pā or Ruapekapeka. The forts could even include underground bunkers, protected by a deep layer of earth over wooden beams, which sheltered the inhabitants during periods of heavy shelling by artillery.[12]

A limiting factor of the Māori fortifications that were not built as set pieces, however, was the need for the people inhabiting them to leave frequently to cultivate areas for food, or to gather it from the wilderness. Consequently, pā would often be seasonally abandoned for 4 to 6 months of each year.[13] In Māori tradition a pā would also be abandoned if a chief was killed or if some calamity took place that a tohunga (witch doctor/shaman) had attributed to an evil spirit (atua). In the 1860s, Māori, though nominally Christian, still followed aspects of their tikanga at the same time. Normally, once the kūmara had been harvested in March–April and placed in storage the inhabitants could lead a more itinerant lifestyle, trading, or harvesting gathering other foodstuffs needed for winter but this did not stop war taking place outside this time frame if the desire for utu or payback was great. To Māori, summer was the normal fighting season[14] and this put them at a huge disadvantage in conflicts with the British Army with its well-organized logistics train which could fight efficiently year round.[citation needed]

Swamp pā

[edit]Fox noted that lake pā were quite common inland in places such as the Waikato. Frequently they appear to have been constructed for whānau (extended family) size groups. The topography was often flat, although a headland or spur location was favoured. The lake frontage was usually protected with a single row of palisades but the landward boundary was protected by a double row. Mangakaware swamp pā, Waikato, had an area of about 3,400 m2. There were 137 palisade post holes identified. The likely total number of posts was about 500. It contained eight buildings within the palisades, six of which have been identified as whare, the largest of which was 2.4 m x 6 m. One building was possibly a cooking shelter and the last a large storehouse. There was one rectangular structure, 1.5 m x 3 m, just outside the swampside palisades which was most likely either a drying rack or storehouse. Swamps and lakes provided eels, ducks, weka (swamp hen) and in some cases fish. The largest of this type was found at Lake Ngaroto, Waikato, the ancient settlement of the Ngāti Apakura, very close to the battle of Hingakaka. This was a built on a much larger scale. Large numbers of carved wooden artefacts were found preserved in the peat. These are on display at the nearby Te Awamutu museum.

Kaiapoi is a well-known example of a pā using swamp as a key part of its defence.[15]

Examples

[edit]

- The old pā remains found on One Tree Hill, close to the centre of Auckland, represent one of the largest known sites as well as one of the largest prehistoric earthworks fortifications known worldwide.[16]

- Pukekura at Taiaroa Head, Otago,[17] established around 1650 and still occupied by Māori in the 1840s.

- Rangiriri (Waikato), a gunfighter pā built in 1863 by Kingites. This pā resembles a very long trench running east–west between the Waikato River and Lake Kopuera with swampy margins. At the high point was a substantial earth works with trenches and parapets. The pā was bombarded from ships and land using Armstrong Guns.

- Nukuhau pā, Waikato River near Stubbs Road. This is a triangular shape pā formed on a flat raised spur with the Waikato River on one side 200m long, a gully with a stream on the long west axis 200 m long and two man made ditches on the narrower southern axis, 107m long. The average slope to the river is 12m at an angle of 70 degrees.

- Huriawa, near Karitane in Otago, occupied a narrow, jagged, and easily defended peninsula built in the mid 18th century by Kāi Tahu chief Te Wera.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ King, Michael (2003). "First Colonisation". The Penguin History of New Zealand (reprint ed.). Penguin Random House New Zealand Limited. ISBN 9781742288260. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

The period of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries has been termed transitional [...]. [...] the practice that developed of preserving kumara tubers in storage pits (a process that had been unnecessary in a tropical climate) meant that communities had to remain with those pits, particularly in an era of larger population when competition for resources meant that less well-provisioned neighbours might be tempted to raid your larder. This last factor more than any other gave impetus to the rise and spread, from north to south, of fortified hilltops which came to be known as pa. They probably originated from a need to protect kumara tubers; but they persisted and became more important when population growth, competition for all resources, the pursuit of mana or authority for one's own group, and a generally more martial culture meant that communities increasingly had to protect themselves from immediate neighbours or from marauding enemies from further afield.

- ^ a b Mackintosh, Lucy (2021). Shifting Grounds: Deep Histories of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Bridget Williams Books. p. 32. doi:10.7810/9781988587332. ISBN 978-1-988587-33-2.

- ^ Murdoch, Graeme (1992). "Wai Karekare - 'The Bay of the Boisterous Seas'". In Northcote-Bade, James (ed.). West Auckland Remembers, Volume 2. West Auckland Historical Society. p. 22. ISBN 0-473-01587-0.

- ^ "The Church Missionary Gleaner, December 1851". The Contrast. Adam Matthew Digital. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Furey, Louise; Emmitt, Joshua; Wallace, Roderick (2017). "Matakawau Stingray Point Pa Excavation, Ahuahu Great Mercury Island 1955–56". Records of the Auckland Museum. 52: 39–57. doi:10.32912/RAM.2018.52.3. ISSN 1174-9202. JSTOR 90016661. Wikidata Q104815050.

- ^ The prehistory of New Zealand. Davidson, Johnson; Longman, Paul. Auckland, 1987 (ISBN 0-582-71812-0).

- ^ The Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand in Relation to Environmental and Biotic Changes. McGlone, M. S.. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 12(s): 115–129, 1989.

- ^ New Zealand History online: First Taranaki war erupts at Waitara

- ^ Chris Pugsley.NZ Defence Quarterly.

- ^ Cowan, James (1955). "The Capture of Rua-pekapeka". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I (1845–64). R.E. Owen, Wellington. p. 74. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Cowan, James (1955). "The Capture of Rua-pekapeka". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I (1845–64). R.E. Owen, Wellington. p. 87. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ a b Early Māori Military Engineering Skills Honoured - engineering dimension, IPENZ, Issue 70, May 2008, Page 09

- ^ (Sutton, Furey and Marshall)

- ^ Basil Keane, 'Riri - traditional Māori warfare - Preparations and entering into battle', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/riri-traditional-maori-warfare/page-5 (accessed 19 January 2021)

- ^ "History of the Kaiapoi Pa". Waimakariri Library. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ One Tree Hill - Use and value Archived 2008-05-21 at the Wayback Machine (from the Auckland volcanic field website of the Auckland Regional Council)

- ^ Pybus, T A (1954). "The Maoris of the South Island". Reed Publishing. p. 37. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

Further reading

[edit]- Potts, Kirsty N. (2014). Murihiku Pa: An Investigation of Pa Sites in the Southern Areas of New Zealand (PDF) (Master of Arts). University of Otago.

- Prickett, Nigel (2016). Fortifications of the New Zealand Wars (PDF) (Report). Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

External links

[edit]- Archaeological Remains of Pā (from Heritage New Zealand website)