Icaridin

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

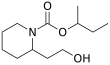

Butan-2-yl 2-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperidine-1-carboxylate | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.102.177 | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C12H23NO3 | |||

| Molar mass | 229.320 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | colorless liquid | ||

| Odor | odorless | ||

| Density | 1.07 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | −170 °C (−274 °F; 103 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 296 °C (565 °F; 569 K) | ||

| 0.82 g/100 mL | |||

| Solubility | 752 g/100mL (acetone) | ||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.4717 | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Icaridin, also known as picaridin, is an insect repellent which can be used directly on skin or clothing.[1] It has broad efficacy against various arthropods such as mosquitos, ticks, gnats, flies and fleas, and is almost colorless and odorless. A study performed in 2010 showed that picaridin spray and cream at the 20% concentration provided 12 hours of protection against ticks.[2] Unlike DEET, icaridin does not dissolve plastics, synthetics or sealants,[3] is odorless and non-greasy[4] and presents a lower risk of toxicity when used with sunscreen, as it may reduce skin absorption of both compounds.[5]

The name picaridin was proposed as an International Nonproprietary Name (INN) to the World Health Organization (WHO), but the official name that has been approved by the WHO is icaridin. The chemical is part of the piperidine family,[1] along with many pharmaceuticals and alkaloids such as piperine, which gives black pepper its spicy taste.

Trade names include Bayrepel and Saltidin among others. The compound was developed by the German chemical company Bayer in the 1980s [6] and was given the name Bayrepel. In 2005, Lanxess AG and its subsidiary Saltigo GmbH were spun off from Bayer[7] and the product was renamed Saltidin in 2008.[8]

Having been sold in Europe (where it is the best-selling insect repellent) since 1998,[9] on 23 July 2020, icaridin was approved again by the EU Commission for use in repellent products. The approval entered into force on 1 February 2022 and is valid for ten years.[10]

Effectiveness

[edit]Icaridin and DEET are the most effective insect repellents available. A 2018 systematic review found no consistent performance difference between icaridin and DEET in field studies and concluded that they are equally preferred mosquito repellents, noting that 50% DEET offers longer protection but is not available in some countries.[11]

Icaridin has been reported to be as effective as DEET at a 20% concentration without the irritation associated with DEET.[12][13] According to the WHO, icaridin “demonstrates excellent repellent properties comparable to, and often superior to, those of the standard DEET.”

Icaridin-based products have been evaluated by Consumer Reports in 2016 as among the most effective insect repellents when used at a 20% concentration.[14] Icaridin was earlier reported to be effective by Consumer Reports (7% solution)[15] and the Australian Army (20% solution).[16] Consumer Reports retests in 2006 gave as result that a 7% solution of icaridin offered little or no protection against Aedes mosquitoes (vector of dengue fever) and a protection time of about 2.5 hours against Culex (vector of West Nile virus), while a 15% solution was good for about one hour against Aedes and 4.8 hours against Culex.[17]

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends using repellents based on icaridin, DEET, ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate (IR3535), or oil of lemon eucalyptus (containing p-menthane-3,8-diol, PMD) for effective protection against mosquitoes that carry the West Nile virus, eastern equine encephalitis and other illnesses.[18]

Adverse effects

[edit]Icaridin can cause mild to moderate eye irritation on contact and is slightly toxic if ingested.[19]

Environmental impact

[edit]A 2018 study found that a commercial repellent product containing 20% icaridin, in what the authors described as "conservative exposure doses", is highly toxic to larval salamanders, a major predator of mosquito larvae.[20] The study observed high larval salamander mortality occurring delayed after the four days of exposure. Because the widely used LC50 test for assessing a chemical's environmental toxicity is based on mortality within four days, the authors suggested that icaridin would be incorrectly deemed as "safe" under the test protocol.[21] However, icaridin was also non-toxic in a 21-day reproduction test on the water flea Daphnia magna[22] and a 32-day early life-stage test in zebrafish.[23]

Since only the icaridin content of the tested repellent product is known, the observed effects cannot be readily attributed to icaridin. Furthermore, the effects of the repellent product showed no dose-response relationship, i.e., there was neither an increase of the magnitude or severity of the observed effects (mortality, tail deformation), nor did the effects occur at earlier time points. The study has been regarded as invalid by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency,[24][25] which has evaluated icaridin prior to its approval under the EU Biocidal Product Regulation. The reasons for rejection were the testing of a mixture of undisclosed composition, the use of a non-standard test organism, the lack of analytical verification of actual test concentrations, and the fact that the test solution was never renewed with the 25 days of study duration.

Mechanism of action

[edit]In 2014, a potential odorant receptor for icaridin (and DEET), CquiOR136•CquiOrco, was suggested for Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito.[26]

Recent crystal and solution studies showed that icaridin binds to Anopheles gambiae odorant binding protein 1 (AgamOBP1). The crystal structure of AgamOBP1•icaridin complex (PDB: 5EL2) revealed that icaridin binds to the DEET-binding site in two distinct orientations and also to a second binding site (sIC-binding site) located at the C-terminal region of the AgamOBP1.[27]

Research on Anopheles coluzzii mosquitoes suggests icaridin does not strongly activate their olfactory receptor neurons, but instead reduces the volatility of the odorants with which it is mixed.[28] By reducing their volatility, icaridin effectively "masks" odorants attractive to mosquitoes on the skin, preventing them from reaching the olfactory receptors to some extent.[28]

Chemistry

[edit]

Icaridin contains two stereocenters: one where the hydroxyethyl chain attaches to the ring, and one where the sec-butyl attaches to the oxygen of the carbamate. The commercial material contains a mixture of all four stereoisomers.

Commercial products

[edit]Commercial products containing icaridin include Cutter Advanced, Muskol, Repeltec,[29] Skin So Soft Bug Guard Plus, Sawyer Picaridin Insect Repellent, Off! FamilyCare, Autan, Smidge, PiActive and MOK.O.[30]

See also

[edit]- DEET

- Ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate (IR3535)

- Permethrin, a pyrethroid insecticide that can be applied to clothing to help prevent bites

- p-Menthane-3,8-diol (PMD)

- SS220, another substituted-piperidine insect repellent

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Picaridin". npic.orst.edu. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ Carroll, Scott P. (5 April 2010). Efficacy Test of KBR 3023 (Picaridin; Icaridin) - Based Personal Insect Repellents (20% Cream and 20% Spray) with Ticks Under Laboratory Conditions (PDF) (Report). LANXESS Corporation. p. 9. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ Picaridin. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011.

- ^ "Picaridin vs DEET: Which Is the Best Insect Repellent?". Appalachian Mountain Club. 4 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Rodriguez J, Maibach HI (2016-01-02). "Percutaneous penetration and pharmacodynamics: Wash-in and wash-off of sunscreen and insect repellent". Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 27 (1): 11–18. doi:10.3109/09546634.2015.1050350. ISSN 0954-6634. PMID 26811157. S2CID 40319483.

- ^ "Picaridin Technical Fact Sheet". National Pesticide information Center.

- ^ "Bayer Completes Spin Off of Lanxess AG". 31 January 2005.

- ^ Saltigo renames insect repellant, Chemical & Engineering News

- ^ "Icaridin - an overview". ScienceDirect. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ "Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/1086 of 23 July 2020 approving icaridin as an existing active substance for use in biocidal products of product-type 19". Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Goodyer, Larry; Schofield, Steven (2018-05-01). "Mosquito repellents for the traveller: does picaridin provide longer protection than DEET?". Journal of Travel Medicine. 25 (Suppl_1): S10–S15. doi:10.1093/jtm/tay005. ISSN 1708-8305. PMID 29718433.

- ^ Journal of Drugs in Dermatology (Jan-Feb 2004) http://jddonline.com/articles/dermatology/S1545961604P0059X/1

- ^ Van Roey K, Sokny M, Denis L, Van den Broeck N, Heng S, Siv S, et al. (December 2014). "Field evaluation of picaridin repellents reveals differences in repellent sensitivity between Southeast Asian vectors of malaria and arboviruses". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (12): e3326. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003326. PMC 4270489. PMID 25522134.

- ^ "Mosquito Repellents That Best Protect Against Zika". Consumer Reports, April, 2016. 30 May 2018.

- ^ - Consumer Reports Confirms Effectiveness Of New Alternative To Deet (link recreated from Wayback Machine Internet Archive - 19 May 2019)

- ^ Frances SP, Waterson DG, Beebe NW, Cooper RD (May 2004). "Field evaluation of repellent formulations containing deet and picaridin against mosquitoes in Northern Territory, Australia". Journal of Medical Entomology. 41 (3): 414–417. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-41.3.414. PMID 15185943.

- ^ "Insect repellents: which keep bugs at bay?" Consumer Reports, June 2006, vol 71 (issue 6), p. 6.

- ^ "Traveler's Health: Avoid bug bites". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ^ "Picaridin Technical Fact Sheet". National Pesticide Information Center. March 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ Almeida RM, Han BA, Reisinger AJ, Kagemann C, Rosi EJ (October 2018). "High mortality in aquatic predators of mosquito larvae caused by exposure to insect repellent". Biology Letters. 14 (10): 20180526. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2018.0526. PMC 6227861. PMID 30381452.

- ^ "Widely used mosquito repellent proves lethal to larval salamanders". Science News. ScienceDaily. Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. 31 October 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ "ECHA - Information on biocides". pp. 231–245. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "ECHA - Information on biocides". pp. 220–229. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "ECHA - Information on biocides". echa.europa.eu. p. 3. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- ^ "Opinion on the application for approval of the active substance Icaridin, Product type: 19". 10 December 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Xu P, Choo YM, De La Rosa A, Leal WS (November 2014). "Mosquito odorant receptor for DEET and methyl jasmonate". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (46): 16592–16597. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11116592X. doi:10.1073/pnas.1417244111. PMC 4246313. PMID 25349401.

- ^ Drakou CE, Tsitsanou KE, Potamitis C, Fessas D, Zervou M, Zographos SE (January 2017). "The crystal structure of the AgamOBP1•Icaridin complex reveals alternative binding modes and stereo-selective repellent recognition". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 74 (2): 319–338. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2335-6. PMC 11107575. PMID 27535661. S2CID 12211128.

- ^ a b Afify A, Betz JF, Riabinina O, Lahondère C, Potter CJ (November 2019). "Commonly Used Insect Repellents Hide Human Odors from Anopheles Mosquitoes". Current Biology. 29 (21): 3669–3680.e5. Bibcode:2019CBio...29E3669A. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.09.007. PMC 6832857. PMID 31630950.

- ^ "Insect Repellent Solutions | Repeltec | AFFIX Labs | Finland". Archived from the original on 2022-08-16. Retrieved 2024-08-08.

- ^ Cha, Ariana Eunjung. "Zika virus FAQ: What is it, and what are the risks as it spreads? The Washington Post. January 21, 2016.