Democratic Kampuchea

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

| 1975–1982 | |||||||||||||

| Anthem: បទនគររាជ Nôkôr Réach "Majestic Kingdom" (1975–1976) ដប់ប្រាំពីរមេសាមហាជោគជ័យ Dâb Prămpir Mésa Môha Choŭkchoăy "Victorious Seventeenth of April" (1976–1982) | |||||||||||||

Location of Democratic Kampuchea | |||||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Phnom Penh | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Khmer | ||||||||||||

| Religion | State atheism[1] | ||||||||||||

| Government | Unitary one-party socialist republic under a totalitarian dictatorship[2][3][4] | ||||||||||||

| CPK General Secretary | |||||||||||||

• 1975–1979 | Pol Pot | ||||||||||||

| Head of state | |||||||||||||

• 1975–1976 | Norodom Sihanouk | ||||||||||||

• 1976–1979 | Khieu Samphan | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||

• 1975–1976 | Penn Nouth | ||||||||||||

• 1976 | Khieu Samphan | ||||||||||||

• 1976–1979 | Pol Pot | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | People's Representative Assembly | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||||||

| 17 April 1975 | |||||||||||||

• Constitution established | 5 January 1976 | ||||||||||||

| 21 December 1978 | |||||||||||||

| 7 January 1979 | |||||||||||||

| 22 June 1982 | |||||||||||||

| Currency | None; monetary system abolished | ||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+07:00 (ICT) | ||||||||||||

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy | ||||||||||||

| Drives on | Right | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Cambodia | ||||||||||||

| History of Cambodia |

|---|

| Early history |

| Post-Angkor period |

| Colonial period |

| Independence and conflict |

| Peace process |

| Modern Cambodia |

| By topic |

|

|

Democratic Kampuchea[a] was the official name of the Cambodian state from 1976 to 1979, under the totalitarian dictatorship of Pol Pot and the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), commonly known as the Khmer Rouge. The Khmer Rouge's capture of the capital Phnom Penh in 1975 effectively ended the United States-backed Khmer Republic of Lon Nol.

From 1975 to 1979, the Khmer Rouge's one-party regime killed millions of its own people through mass executions, forced labour, and starvation, in an event which has come to be known as the Cambodian genocide. The killings ended when the Khmer Rouge were ousted from Phnom Penh by the Vietnamese army. The Khmer Rouge subsequently established a government-in-exile in neighbouring Thailand and retained Kampuchea's seat at the United Nations (UN). In response, Vietnamese-backed communists created a rival government, the People's Republic of Kampuchea, but failed to gain international recognition.

In 1982, the Khmer Rouge established the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) with two non-communist guerrilla factions, broadening the exiled government of Democratic Kampuchea.[5] The exiled government renamed itself the National Government of Cambodia in 1990, in the run-up to the UN-sponsored 1991 Paris Peace Agreements.

Background and establishment

[edit]In 1970, Premier Lon Nol and the National Assembly deposed Norodom Sihanouk as the head of state. Sihanouk, opposing the new government, entered into an alliance with the Khmer Rouge against them. Taking advantage of Vietnamese occupation of eastern Cambodia, massive United States carpet bombing ranging across the country, and Sihanouk's reputation, the Khmer Rouge were able to present themselves as a peace-oriented party in a coalition that represented the majority of the people. Thus, with large popular support in the countryside, the capital Phnom Penh finally fell on 17 April 1975 to the Khmer Rouge.

Thus, prior to the Khmer Rouge's takeover of Phnom Penh in 1975 and the start of Year Zero, Cambodia had already been involved in the Third Indochina War. Tensions between Cambodia and Vietnam were growing due to differences in communist ideology and the incursion of Vietnamese military presence within Cambodian borders. The context of war destabilised the country and displaced Cambodians while making available to the Khmer Rouge the weapons of war. The Khmer Rouge leveraged on the devastation caused by the war to recruit members and used this past violence to justify the similarly, if not more, violent and radical policies of the regime.[6]

The birth of Democratic Kampuchea and its propensity for violence must be understood against this backdrop of war that likely played a contributing factor in hardening the population against such violence and simultaneously increasing their tolerance and hunger for it. Early explanations for the Khmer Rouge brutality suggest that the Khmer Rouge had been radicalised during the war years and later turned this radical understanding of society and violence onto their countrymen.[6] This backdrop of violence and brutality arguably also affected everyday Cambodians, priming them for the violence that they themselves perpetrated under the Khmer Rouge regime.

Phnom Penh fell on 17 April 1975. Sihanouk was given the symbolic position of Head of State for the new government of Democratic Kampuchea and, in September 1975, returned to Phnom Penh from exile in Beijing.[7] After a trip abroad, during which he visited several communist countries and recommended the recognition of Democratic Kampuchea, Sihanouk returned again to Cambodia at the end of 1975. A year after the Khmer Rouge takeover, Sihanouk resigned in mid-April 1976[8] (made retroactive to 2 April 1976) and was placed under house arrest, where he remained until 1979, and the Khmer Rouge remained in sole control.[9]

Evacuation of cities

[edit]In deportations that became markers of the beginning of their rule, the Khmer Rouge demanded and then forced the people to leave the cities and live in the countryside.[10] Phnom Penh—populated by 2.5 million people[11] —was soon nearly empty. The roads out of the city were clogged with evacuees. Similar evacuations occurred throughout the nation.

The conditions of the evacuation and the treatment of the people involved often depended on which military units and commanders were conducting the specific operations. Pol Pot's brother – Chhay, who worked as a Republican journalist in the capital – was reported to have died during the evacuation of Phnom Penh.

Even Phnom Penh's hospitals were emptied of their patients.[12] The Khmer Rouge provided transportation for some of the aged and the disabled, and they set up stockpiles of food outside the city for the refugees; however, the supplies were inadequate to sustain the hundreds of thousands of people on the road. Even seriously injured hospital patients, many without any means of conveyance, were summarily forced to leave regardless of their condition.

The foreign community, about 800 people, was quarantined in the French embassy compound, and by the end of the month the foreigners were taken by truck to the Thai border. Khmer women who were married to foreigners were allowed to accompany their husbands, but Khmer men were not permitted to leave with their foreign wives.

Western historians claim that the motives were political, based on deep-rooted resentment of the cities. The Khmer Rouge was determined to turn the country into a nation of peasants in which the corruption and "parasitism" of city life would be completely uprooted. In addition, Pol Pot wanted to break up the "enemy spy organisations" that allegedly were based in the urban areas. Finally, it seems that Pol Pot and his hard-line associates on the CPK Political Bureau used the forced evacuations to gain control of the city's population and to weaken the position of their factional rivals within the communist party.[13]

Constitution

[edit]The Khmer Rouge abolished the Royal Government of National Union of Kampuchea (GRUNK, established in 1970) and promulgated the Constitution of Democratic Kampuchea on 5 January 1976.[citation needed]

The Khmer Rouge continued to use Sihanouk as a figurehead for the government until 2 April 1976 when Sihanouk resigned as head of state. Sihanouk remained under comfortable, but insecure, house arrest in Phnom Penh, until late in the war with Vietnam he departed for the United States where he made Democratic Kampuchea's case before the Security Council. He eventually relocated to China.

The "rights and duties of the individual" were briefly defined in Article 12. They included none of what are commonly regarded as guarantees of political human rights[citation needed] except the statement that "men and women are equal in every respect." The document declared, however, that "all workers" and "all peasants" were "masters" of their factories and fields. An assertion that "there is absolutely no unemployment in Democratic Kampuchea" rings true in light of the regime's massive use of force.

The constitution defined Democratic Kampuchea's foreign policy principles in Article 21, the document's longest, in terms of "independence, peace, neutrality, and nonalignment." It pledged the country's support to anti-imperialist struggles in the Third World. In light of the regime's aggressive attacks against Vietnamese, Thai, and Lao territory during 1977 and 1978, the promise to "maintain close and friendly relations with all countries sharing a common border" bore little resemblance to reality.

Governmental institutions were outlined very briefly in the constitution. The legislature, the Kampuchean People's Representative Assembly (KPRA), contained 250 members "representing workers, peasants, and other working people and the Kampuchean Revolutionary army." One hundred and fifty KPRA seats were allocated for peasant representatives; fifty, for the armed forces; and fifty, for worker and other representatives. The legislature was to be popularly elected for a five-year term. Its first and only election was held on 20 March 1976. "New People" apparently were not allowed to participate.

The executive branch of government also was chosen by the KPRA.[citation needed] It consisted of a state presidium "responsible for representing the state of Democratic Kampuchea inside and outside the country." It served for a five-year term, and its president was head of state. Khieu Samphan was the only person to serve in this office, which he assumed after Sihanouk's resignation. The judicial system was composed of "people's courts", the judges for which were appointed by the KPRA, as was the executive branch.

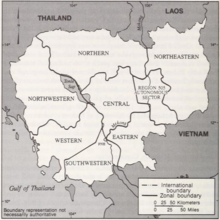

The constitution did not mention regional or local government institutions. After assuming power, the Khmer Rouge abolished the old provinces (ខេត្ត khet) and replaced them with seven zones (ភូមិភាគ phoumipheak); the Northern Zone, Northeastern Zone, Northwestern Zone, Central Zone, Eastern Zone, Western Zone, and Southwestern Zone. There were also two other regional-level units: the Kracheh Special Region Number 505 and, until 1977, the Siemreab Special Region Number 106.

The zones were divided into regions (តំបន់ damban) that were given numbers. Number One, appropriately, encompassed the Samlot region of the Northwestern Zone (including Battambang Province), where the insurrection against Sihanouk had erupted in early 1967. With this exception, the damban appear to have been numbered arbitrarily.

The damban were divided into districts (ស្រុក srok), communes (ឃុំ khum), and villages (ភូមិ phum), the latter usually containing several hundred people. This pattern was roughly similar to that which existed under Sihanouk and the Khmer Republic, but inhabitants of the villages were organized into groups (ក្រុម krom) composed of ten to fifteen families. On each level, administration was directed by a three-person committee (kanak, or kena).

CPK members occupied committee posts at the higher levels. Subdistrict and village committees were often staffed by local poor peasants, and, very rarely, by "new people." Cooperatives (សហករណ៍ sahakor), similar in jurisdictional area to the khum, assumed local government responsibilities in some areas.

Organisation

[edit]In January 1976, the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) promulgated the Constitution of Democratic Kampuchea. The constitution provided for a Kampuchean People's Representative Assembly (KPRA) to be elected by secret ballot in direct general elections and a State Praesidium to be selected and appointed every five years by the KPRA. The KPRA met only once, a three-day session in April 1976. However, members of the KPRA were never elected, as the Central Committee of the CPK appointed the chairman and other high officials both to it and to the State Praesidium. Plans for elections of members were discussed, but the 250 members of the KPRA were in fact appointed by the upper echelon of CPK.

All power belonged to the Standing Committee of CPK, the membership of which comprised the Secretary and Prime Minister Pol Pot, his Deputy Secretary Nuon Chea and seven others. It was known also as the "Centre", the "Organisation" or "Angkar", and its daily work was conducted from Office 870 in Phnom Penh. For almost two years after the takeover, the Khmer Rouge continued to refer to itself as simply Angkar. It was only in a March 1977 speech that Pol Pot revealed the CPK's existence. It was also around that time that it was confirmed that Pol Pot was the same person as Saloth Sar, who had long been cited as the CPK's general secretary.

Administrative

[edit]

The Khmer Rouge government did away with all former Cambodian traditional administrative divisions. Instead of provinces, Democratic Kampuchea was divided into geographic zones, derived from divisions established by the Khmer Rouge when they fought against the ill-fated Khmer Republic led by General Lon Nol.[15] There were seven zones, namely the Northwest, the North, the Northeast, the East, the Southwest, the West and the center, plus two Special Regions, i.e. the Kratie Special Region no 505 and (before mid-1977) the Siemreap Special Region no 106.[16]

The regions were subdivided into smaller areas or tâmbán. These were known by numbers, which were assigned without a seemingly coherent pattern. Villages were also subdivided into 'groups' (ក្រុម krŏm) of 15–20 households who were led by a group leader (មេក្រុម mé krŏm).

Legal

[edit]The Khmer Rouge dismantled the legal and judicial structures of the Khmer Republic. There were no courts, judges, laws or trials in Democratic Kampuchea. The "people’s courts" stipulated in Article 9 of the constitution were never established. The old legal structures were replaced by re-education, interrogation and security centres where former Khmer Republic officials and supporters as well as others were detained and executed.[17]

Military

[edit]

After the establishment of Democratic Kampuchea, the 68,000-member Khmer Rouge-dominated CPNLAF (Cambodian People's National Liberation Armed Forces) force, which completed its conquest of Phnom Penh, Cambodia in April 1975, was renamed the RAK (Kampuchea Revolutionary Army). This name dated back to the peasant uprising that broke out in the Samlout District of Battambang province in 1967. Under its long-time commander and then Minister of Defense Son Sen, the RAK had 230 battalions in 35 to 40 regiments and in 12 to 14 brigades. The command structure in units was based on three-person committees in which the political commissar ranked higher than the military commander and his deputy.

Cambodia was divided into zones and special sectors by the RAK, the boundaries of which changed slightly over the years. Within these areas, the RAK's first task was the peremptory execution of former Khmer National Armed Forces (FANK) officers and of their families, without trial or fanfare to eliminate Khmer Rouge enemies. The RAK's next priority was to consolidate into a national army the separate forces that were operating more or less autonomously in the various zones. The Khmer Rouge units were commanded by zonal secretaries who were simultaneously party and military officers, some of whom were said to have manifested "warlord characteristics".[18]

Troops from one zone were frequently sent to another zone to enforce discipline. These efforts to discipline zonal secretaries and their dissident or ideologically impure cadres gave rise to the purges that were to decimate RAK ranks, to undermine the morale of the victorious army, and to generate the seeds of rebellion.[18] In this way, the Khmer Rouge used the RAK to sustain and fuel its violent campaign.

Society

[edit]According to Pol Pot, Cambodia was made up of four classes: peasants, proletariat, bourgeoisie, and feudalists. Post-revolutionary society, as defined by the 1976 constitution of Democratic Kampuchea, consisted of workers, peasants, and "all other Kampuchean working people."[citation needed] No allowance was made for a transitional stage such as China's New Democracy in which "patriotic" landlord or bourgeois elements were permitted to play a role in socialist construction.[dubious – discuss] Sihanouk writes that in 1975 he, Khieu Samphan, and Khieu Thirith went to visit Zhou Enlai, who was gravely ill. Zhou warned them not to attempt to achieve communism in a single step, as China had attempted in the late 1950s with the Great Leap Forward. Khieu Samphan and Khieu Thirith "just smiled an incredulous and superior smile."[19] Khieu Samphan and Son Sen later boasted to Sihanouk that "we will be the first nation to create a completely communist society without wasting time on intermediate steps."[19]

Although conditions varied from region to region, a situation that was, in part, a reflection of factional divisions that still existed within the CPK during the 1970s, the testimony of refugees reveals that the most salient social division was between the politically suspect "new people", those driven out of the towns after the communist victory, and the more reliable "old people", the peasants who had remained in the countryside.[citation needed] The working class was a negligible factor because of the evacuation of the urban areas and the idling of most of the country's few factories. The one important working class group in pre-revolutionary Cambodia—labourers on large rubber plantations—traditionally had consisted mostly of Vietnamese immigrants and thus was politically suspect.[citation needed]

The number of people, including refugees, living in the urban areas on the eve of the communist victory probably was somewhat more than 3 million,[citation needed] out of the total population of roughly 8 million. As mentioned, despite their rural origins, the refugees were considered "new people"—that is, people unsympathetic to Democratic Kampuchea. Some doubtless passed as "old people" after returning to their native villages, but the Khmer Rouge seem to have been extremely vigilant in recording and keeping track of the movements of families and of individuals.[20]

The lowest unit of social control, the krom (group), consisted of ten to fifteen nuclear families whose activities were closely supervised by a three-person committee. The committee chairman was selected by the CPK. This grassroots leadership was required to note the social origin of each family under its jurisdiction and to report it to persons higher up in the Angkar hierarchy. The number of "new people" may initially have been as high as 2.5 million.[citation needed]

The "new people" were treated as forced labourers. They were constantly moved, were forced to do the hardest physical labour, and worked in the most inhospitable, fever-ridden parts of the country, such as forests, upland areas, and swamps. "New people" were segregated from "old people", enjoyed little or no privacy, and received the smallest rice rations. When the country experienced food shortages in 1977, the "new people" suffered the most.[20] The medical care available to them was primitive or nonexistent. Families often were separated because people were divided into work brigades according to age and sex and sent to different parts of the country.[21] "New people" were subjected to unending political indoctrination and could be executed without trial.[22]

The situation of the "old people" under Khmer Rouge rule was more ambiguous. Refugee interviews reveal cases in which villagers were treated as harshly as the "new people", enduring forced labour, indoctrination, the separation of children from parents, and executions; however, they were generally allowed to remain in their native villages.[20] Because of their age-old resentment of the urban and rural elites, many of the poorest peasants probably were sympathetic to Khmer Rouge's goals. In the early 1980s, visiting Western journalists found that the issue of peasant support for the Khmer Rouge was an extremely sensitive subject that officials of the People's Republic of Kampuchea were not inclined to discuss.[citation needed]

Although the Southwestern Zone was one original centre of power of the Khmer Rouge, and cadres administered it with strict discipline, random executions were relatively rare, and "new people" were not persecuted if they had a cooperative attitude. In the Western Zone and in the Northwestern Zone, conditions were harsh. Starvation was general in the latter zone because cadres sent rice to Phnom Penh rather than distributing it to the local population. In the Northern Zone and in the Central Zone, there seem to have been more executions than there were victims of starvation.[23] Little reliable information emerged on conditions in the Northeastern Zone, one of the most isolated parts of Cambodia.

On the surface, society in Democratic Kampuchea was strictly egalitarian. The Khmer language, like many in Southeast Asia, has a complex system of usages to define speakers' rank and social status. These usages were abandoned, and people were forbidden to speak any language other than Khmer. Neologisms were introduced, and everyday vocabulary was altered to encourage a more collectivist mentality. People were encouraged to call each other "friend", or "comrade" (in Khmer, មតដ mitt), and to avoid traditional signs of deference such as bowing or folding the hands in salutation. They were also encouraged to talk about themselves in the plural "we" rather than the singular "I".[24] Aspects of life from the Khmer Republic such as art, television, mail, books, movies, music, and personal vehicles were prohibited.[25] The language was transformed in other ways. The Khmer Rouge invented new terms. People were told they must "forge" (លត់ដំ lot dam) a new revolutionary character, that they were the "instruments" (ឧបករណ៍ opokar) of the Angkar, and that nostalgia for pre-revolutionary times (ឈឺសតិអារម្មណ៍ chheu satek arom, or "memory sickness") could result in their receiving Angkar's "invitation" to be deindustrialised and to live in a concentration camp.[citation needed]

Despite the ideological commitment to radical equality, CPK members, local-level leaders of poor peasant backgrounds who collaborated with Angkar, and the armed forces constituted a clearly recognizable elite. They had a higher standard of living and received special privileges not enjoyed by the rest of the population. Refugees agree that, even during times of severe food shortages, members of the grassroots elite had adequate, if not luxurious, supplies of food.[26] One refugee wrote that "pretty new bamboo houses" were built for Khmer Rouge cadres along the river in Phnom Penh. Members of the Central Committee could go to China for medical treatment,[27] and the highest echelons of the party had access to imported luxury products.[28]

They also had a tendency to nepotism similar of the Sihanouk-era elite. Pol Pot's wife, Khieu Ponnary, was head of the Association of Democratic Khmer Women and her younger sister, Khieu Thirith, served as minister of social action. These two women were considered among the half-dozen most powerful personalities in Democratic Kampuchea. Son Sen's wife, Yun Yat, served as minister for culture, education and learning.[citation needed] Several of Pol Pot's nephews and nieces were given jobs in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. One of Ieng Sary's daughters was appointed head of the Calmette Hospital although she had not graduated from secondary school. A niece of Ieng Sary was given a job as English translator for Radio Phnom Penh although her fluency in the language was relative.[citation needed] Family ties were important, both because of the culture and because of the leadership's intense secretiveness and distrust of outsiders, especially of pro-Vietnamese communists. Different ministries, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Industry, were controlled and exploited by powerful Khmer Rouge families. Administering the diplomatic corps was regarded as an especially profitable fiefdom.[citation needed]

According to Craig Etcheson, an authority on Democratic Kampuchea, members of the revolutionary army lived in self-contained colonies, and they had a "distinctive warrior-caste ethos." Armed forces units personally loyal to Pol Pot, known as the "Unconditional Divisions", were a privileged group within the military.[citation needed]

The Khmer Rouge regime was also characterized by "totalitarian puritanism" with any sex before marriage being punishable by death in many cooperatives and zones.[29]

Education

[edit]The Khmer Rouge regarded traditional education with undiluted hostility. After the fall of Phnom Penh, they executed thousands of teachers. Those who had been educators prior to 1975 survived by hiding their identities.[citation needed] Aside from teaching basic mathematical skills and literacy, the major goal of the new educational system was to instill revolutionary values in the young. For a regime at war with most of Cambodia's traditional values, this meant that it was necessary to create a gap between the values of the young and the values of the nonrevolutionary old.

The regime recruited children to spy on adults. The pliancy of the younger generation made them, in Angkar's words, the "dictatorial instrument of the party."[30] In 1962 the communists had created a special secret organisation, the Democratic Youth League, that, in the early 1970s, changed its name to the Communist Youth League of Kampuchea. Pol Pot considered Youth League alumni as his most loyal and reliable supporters and used them to gain control of the central and the regional CPK apparatus.[citation needed] The powerful Khieu Thirith, minister of social action, was responsible for directing the youth movement.[citation needed] Hardened young cadres, many little more than twelve years of age, were enthusiastic accomplices in some of the regime's worst atrocities. Sihanouk, who was kept under virtual house arrest in Phnom Penh between 1976 and 1978, wrote in War and Hope that his youthful guards, having been separated from their families and given a thorough indoctrination, were encouraged to play cruel games involving the torture of animals. Having lost parents, siblings, and friends in the war and lacking the Buddhist values of their elders, the Khmer Rouge youth also lacked the inhibitions that would have dampened their zeal for revolutionary terror.[citation needed]

Health

[edit]Health facilities in the years 1975 to 1979 were abysmally poor. Many physicians either were executed or were prohibited from practicing. It appears that the party and the armed forces elite had access to Western medicine and to a system of hospitals that offered reasonable treatment, but ordinary people, especially "new people", were expected to use traditional plant and herbal remedies that were of debatable usefulness. Some bartered their rice rations and personal possessions to obtain aspirin and other simple drugs.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]Article 20 of the 1976 constitution of Democratic Kampuchea guaranteed religious freedom, but it also declared that "all reactionary religions that are detrimental to Democratic Kampuchea and the Kampuchean People are strictly forbidden." About 85 percent of the population followed the Theravada school of Buddhism. The country's 40,000 to 60,000 Buddhist monks, regarded by the regime as social parasites, were defrocked and forced to work in the rural co-operatives and irrigation projects.[21] Many monks were executed; temples and pagodas were destroyed[31] or turned into storehouses. Images of the Buddha were defaced and dumped into rivers and lakes. People who were discovered praying or expressing religious sentiments were often killed.[citation needed]

The Christian and Muslim communities, considered part of a pro-Western cosmopolitan sphere, were fiercely persecuted for hindering Cambodian culture and society. The Roman Catholic cathedral of Phnom Penh was completely razed.[31] The Khmer Rouge forced Muslims to eat pork, which they regard as forbidden (ḥarām). Many of those who refused were killed. Christian clergy and Muslim imams were executed. One hundred and thirty Cham mosques were destroyed.[31]

Despite its ideological iconoclasm, many historical monuments were left undamaged by the Khmer Rouge;[32] for Pol Pot's government, like its predecessors, the historic state of Angkor was a key point of reference.[33]

Ethnic minorities

[edit]The Khmer Rouge banned by decree the existence of ethnic Chinese, Vietnamese, Muslim Cham, and 20 other minorities, which altogether constituted 15% of the population at the beginning of the Khmer Rouge's rule.[34] Tens of thousands of Vietnamese were raped, mutilated, and murdered in regime-organised massacres. Most of the survivors fled to Vietnam.[citation needed]

The Cham, a Muslim minority who are the descendants of migrants from the old state of Champa, were forced to adopt the Khmer language and customs. Their communities, which traditionally had existed apart from Khmer villages, were broken up. Forty thousand Cham were killed in two districts of Kampong Cham Province alone. Thai minorities living near the Thai border also were persecuted.[citation needed]

The state of the Chinese Cambodians was described as "the worst disaster ever to befall any ethnic Chinese community in Southeast Asia".[34] Cambodians of Chinese descent were massacred by the Khmer Rouge under the justification that they "used to exploit the Cambodian people".[35] The Chinese were stereotyped as traders and moneylenders, and therefore were associated with capitalism. Among the Khmer, the Chinese were also resented for their lighter skin color and cultural differences.[36] Hundreds of Chinese families were rounded up in 1978 and told that they were to be resettled, but were actually executed.[35] At the beginning of the Khmer Rouge's rule in 1975, there were 425,000 ethnic Chinese in Cambodia. By the end in 1979, there were 200,000. In addition to being a proscribed ethnic group by the government, the Chinese were predominantly city-dwellers, making them vulnerable to the Khmer Rouge's revolutionary ruralism.[34] The government of the People's Republic of China did not protest the killings of ethnic Chinese in Cambodia.[35] The policies of the Khmer Rouge towards Sino-Cambodians seem puzzling in light of the fact that the two most powerful people in the regime and presumably the originators of the racist doctrine, Pol Pot and Nuon Chea, both had mixed Chinese-Cambodian ancestry. Other senior figures in the Khmer Rouge state apparatus, such as Son Sen and Ta Mok, also had Chinese ethnic heritage.[citation needed]

In the late 1980s, little was known of Khmer Rouge policies toward the tribal peoples of the northeast, the Khmer Loeu. Pol Pot established an insurgent base in the tribal areas of Ratanakiri Province in the early 1960s, and he may have had a substantial Khmer Loeu following. Predominantly animist peoples, with few ties to the Buddhist culture of the lowland Khmers, the Khmer Loeu had resented Sihanouk's attempts to "civilise" them.[citation needed]

There were also high rates of sexual violence during the regime.[37]

Terror

[edit]

A security apparatus called Santebal was part of the Khmer Rouge organizational structure well before 17 April 1975, when the Khmer Rouge took control over Cambodia. Son Sen,[38] later the Deputy Prime Minister for Defense of Democratic Kampuchea, was in charge of the Santebal, and in that capacity he appointed Kang Kek lew (Comrade Duch) to run its security apparatus. When the Khmer Rouge took power in 1975, Duch moved his headquarters to Phnom Penh and reported directly to Son Sen. At that time, a small chapel in the capital was used to incarcerate the regime's prisoners, who totaled fewer than two hundred. In May 1976, Duch moved his headquarters to its final location, a former high school known as Tuol Sleng, which could hold up to 1,500 prisoners.

The Khmer Rouge government arrested, tortured, and eventually executed anyone suspected of belonging to several categories of supposed "enemies":

- Anyone with connections to the former government or with foreign governments.

- Professionals and intellectuals—in practice this included almost everyone with an education, people who understood a foreign language, and even people who required glasses.[39] However, ironically, Pol Pot himself was a university-educated man (albeit a drop-out) with a taste for French literature and was also a fluent French speaker. Many artists, including musicians, writers, and filmmakers were executed. Some like Ros Serey Sothea, Pen Ran, and Sinn Sisamouth gained posthumous fame for their talents and are still popular with Khmers today.

- Ethnic Vietnamese, ethnic Chinese, ethnic Thai and other minorities in Eastern Highland, Cambodian Christians (most of whom were Catholic, and the Catholic Church in general), Muslims and the Buddhist monks.

- "Economic saboteurs:" many of the former urban dwellers (who had not starved to death in the first place) were deemed to be guilty by virtue of their lack of agricultural ability.

Through the 1970s, and especially after mid-1975, the party was also shaken by factional struggles. There were even armed attempts to topple Pol Pot. The resultant purges reached a crest in 1977 and 1978 when thousands, including some important KCP leaders, were executed.

Today, examples of the torture methods used by the Khmer Rouge can be seen at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. The museum occupies the former grounds of a high school turned prison camp that was operated by Comrade Duch.

The torture system at Tuol Sleng was designed to make prisoners confess to whatever crimes they were charged with by their captors. In their confessions, the prisoners were asked to describe their personal backgrounds. If they were party members, they had to say when they joined the revolution and describe their work assignments in Democratic Kampuchea. Then the prisoners would relate their supposed treasonous activities in chronological order. The third section of the confession text described prisoners' thwarted conspiracies and supposed treasonous conversations. In the end, the confessions would list a string of traitors who were the prisoners' friends, colleagues, or acquaintances. Some lists contained over a hundred names. People whose names were on the confession list were often called in for interrogation.[40] Typical confessions ran into thousands of words in which the prisoner would interweave true events in their lives with imaginary accounts of their espionage activities for the CIA, the KGB, or Vietnam.[41]

Seventeen thousand people passed through Security Prison 21 (now the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum),[42] before they were taken to sites (also known as the Killing Fields), outside Phnom Penh, such as Choeung Ek, where most were executed (often with pickaxes, to save bullets)[43] and buried in mass graves. Of the thousands who entered Tuol Sleng, only twelve are known to have survived.

Explaining the violence

[edit]Violence as a collective action

[edit]

While the historical context and ideological underpinnings of the Khmer Rouge regime provide reasons for why the Cambodian genocide occurred, more explanations must be had for the widespread violence that was carried out by Cambodians against Cambodians. Anthropologist Alexander Hinton's research project to interview perpetrators of violence during the Khmer Rouge regime sheds some light on the question of collective violence. Hinton's analysis of top-down initiatives shows that perpetrators in the Khmer Rouge were motivated to kill because Khmer Rouge leaders were effectively able to "localize their ideologies" to appeal to their followers.[36]

Specifically, Hinton spoke to two ideological palimpsests that the Khmer Rouge used. First, the Khmer Rouge tapped on the Khmer notion of disproportionate revenge to motivate a resonant equivalent—class rage against previous oppressors.[36] Hinton uses the example of revenge in the Cambodian context to illustrate how closely violence can be tied to and explained by the Buddhist notion of karma, which dictates that there is a cycle of cause and effect in which one's past actions will affect one's future life.[36]

Next, the Khmer Rouge leadership built on local notions of power and patronage vis-à-vis Wolters’ mandala polity to establish their authority as a potent centre.[36] In so doing, the Khmer Rouge escalated the suspicion and instability inherent within such patronage networks, setting the stage for distrust and competition on which political purges were based.[citation needed]

Violence as an individual action

[edit]Under the Khmer Rouge, the encroachment of the public sphere into that which was once private space made constant group-level interactions. Within these spaces, cultural models such as face, shame, and honour were adapted to Khmer Rouge notions of social status and bound up with revolutionary consciousness.[36]

Thus, individuals were judged and their social status was based on these adapted Khmer Rouge conceptions of hierarchy which were predominantly political in nature. Within this framework, the Khmer Rouge constructed essentialised categories of identity which crystallised difference and inscribed these differences on victim's bodies, providing the logic and impetus for violence. To save face and preserve one's social status within the Khmer Rouge hierarchy, Hinton argues that first, violence was practised by cadres to avoid shame or loss of face; and second, that shamed cadres could restore their face through perpetrating violence.[36] At the level of individuals, the need for social approval and belonging to a community, even one as twisted as the Khmer Rouge, contributed to obedience, motivating violence within Cambodia.[citation needed]

Economy

[edit]Democratic Kampuchea's economic policy was similar to, and possibly inspired by, China's radical Great Leap Forward that carried out immediate collectivisation of the Chinese countryside in 1958.[44] During the early 1970s, the Khmer Rouge established "mutual assistance groups" in the areas they occupied.[citation needed]

After 1973, these were organised into "low-level cooperatives" in which land and agricultural implements were lent by peasants to the community but remained their private property. "High-level cooperatives", in which private property was abolished and the harvest became the collective property of the peasants, appeared in 1974. "Communities", introduced in early 1976, were a more advanced form of high-level cooperative in which communal dining was instituted. State-owned farms also were established.[citation needed]

Far more than the Chinese communists, the Khmer Rouge pursued the ideal of economic self-sufficiency, specifically the version that Khieu Samphan had outlined in his 1959 doctoral dissertation. Currency was abolished, and domestic trade or commerce could be conducted only through barter. Rice, measured in tins, became the most important medium of exchange, although people also bartered gold, jewelry, and other personal possessions.[citation needed]

Foreign trade was almost completely halted, though there was a limited revival in late 1976 and early 1977. China was the most important trading partner, but commerce amounting to a few million dollars was also conducted with France, the United Kingdom, and with the United States through a Hong Kong intermediary.[citation needed]

From the Khmer Rouge perspective, the country was free of foreign economic domination for the first time in its 2,000-year history. By mobilising the people into work brigades organised in a military fashion, the Khmer Rouge hoped to unleash the masses' productive forces.[citation needed]

There was an "Angkorian" component to economic policy. That ancient kingdom had grown rich and powerful because it controlled extensive irrigation systems that produced surpluses of rice. Agriculture in modern Cambodia depended, for the most part, on seasonal rains.[citation needed] By building a nationwide system of irrigation canals, dams, and reservoirs, the leadership believed it would be possible to produce rice on a year-round basis. It was the "new people" who suffered and sacrificed the most to complete these ambitious projects.[citation needed]

Although the Khmer Rouge implemented an "agriculture first" policy in order to achieve self-sufficiency, they were not, as some observers have argued, "back-to-nature" primitivists. Although the 1970–75 war and the evacuation of the cities had destroyed or idled most industry, small contingents of workers were allowed to return to the urban areas to reopen some plants.[citation needed]

Like their Chinese counterparts, the Cambodian communists had great faith in the inventive power and the technical aptitude of the masses, and they constantly published reports of peasants' adapting old mechanical parts to new uses. Similar to Mao's regime, which had attempted unsuccessfully to build a new steel industry based on backyard furnaces during the Great Leap Forward, the Khmer Rouge sought to move industry to the countryside. Significantly, the seal of Democratic Kampuchea displayed not only sheaves of rice and irrigation sluices, but also a factory with smokestacks.[citation needed]

Foreign relations

[edit]

The Democratic Kampuchea regime maintained close ties with China, its main backer, and to a lesser extent with North Korea. In 1977, in a message congratulating the Cambodian comrades on the 17th anniversary of the CPK, Kim Jong-il congratulated the Cambodian people for having "wiped out counterrevolutionary group of spies who had committed subversive activities and sabotage[45]".

On taking power, the Khmer Rouge spurned both the Western states and the Soviet Union as sources of support.[46] Instead, China became Cambodia's main international partner.[47] With Vietnam increasingly siding with the Soviet Union over China, the Chinese saw Pol Pot's government as a bulwark against Vietnamese influence in Indochina.[48] It is estimated that at least 90% of the foreign aid which the Khmer Rouge received came from China, and in 1975 alone, at least US$1 billion in interest-free economic and military aid came from China.[49][50][51] The relationship between the Chinese and Cambodian governments was nevertheless marred by mutual suspicion and China had little influence on Pol Pot's domestic policies.[52] It had a greater influence on Cambodia's foreign policy, successfully pushing the country to pursue rapprochement with Thailand and open communication with the U.S. to combat Vietnamese influence in the region.[53] After Mao died in September 1976, Pol Pot praised him and Cambodia declared an official period of mourning.[54] In November 1976, Pol Pot travelled secretly to Beijing, seeking to retain his country's alliance with China after the Gang of Four were arrested.[55] From Beijing, he was then taken on a tour of China, visiting sites associated with Mao and the Chinese Communist Party.[56]

While Democratic Kampuchea held Cambodia's UN seat and was internationally recognized, only the following countries had an embassy in Cambodia: Burma, Albania, People's Republic of China, North Korea, Cuba, Egypt, Laos, Romania, Vietnam and Yugoslavia.[57] Democratic Kampuchea itself, on the other hand, established embassies in various countries: Albania, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, People's Republic of China, North Korea, Cuba, Egypt, Romania, Laos, Sweden, Tanzania, USSR, Vietnam and Yugoslavia.[58] The Chinese were the only country allowed to retain their old Phnom Penh embassy.[59] All other diplomats were made to live in assigned quarters on the Boulevard Monivong. This street was barricaded off and the diplomats were not permitted to leave without escorts. Their food was brought to them and provided through the only shop that remained open in the country.[60]

Ideology

[edit]Ideological influences

[edit]The Khmer Rouge was heavily influenced by Mao Zedong,[61] the French Communist Party and the writings of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin[62] as well as ideas of Khmer racial superiority.[63] Turning to look at the roots of the ideology which guided the Khmer Rouge intellectuals behind the revolution, it becomes evident that the roots of such radical thought can be traced to an education in France that started many of the top Khmer Rouge officials on the road to thinking that communism demanded violence.[64][65]

Influences from the French Revolution led many who studied in Paris to believe that Marxist political theory that was based on class struggle could be applied to the national cause in Cambodia.[66] The premise of class struggle sowed the ideological seeds for violence and made violence appear all the more necessary for the revolution to succeed. In addition, because many of the top Khmer Rouge officials such as Pol Pot, Khieu Samphan and Kang Kek Iew (also known as Duch) were educators and intellectuals, they were unable to connect with the masses and were alienated upon their return to Cambodia, further fuelling their radical thought.[65]

Michael Vickery downplays the importance of personalities in explaining the Democratic Kampuchea phenomenon, noting that Democratic Kampuchea leaders were never considered evil by prewar contemporaries. This view is challenged by some including Rithy Phan, who after interviewing Duch, the head of Tuol Sleng, seems to suggest that Duch was a fearsome individual who preyed on and seized upon the weaknesses of others. All in all, the historical context of civil war, coupled with the ideological ferment in Cambodian intellectuals returning from France, set the stage for the Khmer Rouge revolution and the violence that it would propagate.[67][68]

Operationalising ideology through violence

[edit]The Khmer Rouge was determined to turn the country into a nation of peasants in which the corruption and "parasitism" of city life would be completely uprooted. Communalisation was implemented by putting men, women and children to work in the fields, which disrupted family life. The regime claimed to have "liberated" women through this process and according to Zal Karkaria "appeared to have implemented Engels's doctrine in its purest form: women produced, therefore they had been freed".[69]

Under the leadership of Pol Pot, cities were emptied, organised religion was abolished, and private property, money and markets were eliminated.[70] An unprecedented genocide campaign ensued that led to annihilation of about 25% of the country's population, with much of the killing being motivated by Khmer Rouge ideology which urged "disproportionate revenge" against rich and powerful oppressors.[71][72][73] Victims included such class enemies as rich capitalists, professionals, intellectuals, police and government employees (including most of Lon Nol's leadership),[74] along with ethnic minorities such as Chinese, Vietnamese, Lao and Cham.[75]

The Khmer Rouge regime was one of the most brutal in recorded history, especially considering how briefly it ruled the country. Based on an analysis of mass grave sites, the DC-Cam Mapping Program and Yale University estimated that the Khmer Rouge executed over 1.38 million people.[76][77] If deaths from disease and starvation are counted, as many as 2.5 million people died as a result of Khmer Rouge rule.[78] This included most of the country's minority populations. For instance, the country's ethnic Vietnamese population was almost completely wiped out; nearly all ethnic Vietnamese who did not flee immediately after the takeover were exterminated.

Fall and aftermath

[edit]Not content with ruling Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge leaders also dreamed of reviving the Angkorian empire of a thousand years earlier, which ruled over large parts of what today are Thailand and Vietnam. This involved launching military attacks into southern Vietnam in which thousands of unarmed villagers were massacred.

Immediately following the Khmer Rouge victory in 1975, there were skirmishes between their troops and Vietnamese forces. Many incidents occurred in May 1975. The Cambodians launched attacks on the Vietnamese islands of Phú Quốc and Thổ Chu causing the death of over 500 civilians[79] and intruded into Vietnamese border provinces. In late May, at about the same time that the United States launched an airstrike against the oil refinery at Kompong Som, following the Mayagüez incident, Vietnamese forces seized the Cambodian island of Poulo Wai. According to Republic of Vietnam, Poulo Wai was a part of Vietnam since the 18th century and the island was under Cambodian administrative management in 1939 in accordance with the decisions of French colonists. Vietnam has recognized Poulo Wai as part of Cambodia since 1976, and the recognition is seen as a sign of goodwill by Vietnam to preserve its relationship with Cambodia.[80]

The following month, Pol Pot, Nuon Chea, and Ieng Sary travelled secretly to Hanoi in May, where they proposed a Friendship Treaty between the two countries. In the short term, this successfully eased tensions.[81] Although the Vietnamese evacuated Poulo Wai in August, incidents continued along Cambodia's northeastern border. At the instigation of the Phnom Penh regime, thousands of Vietnamese also were driven out of Cambodia.

In May, Cambodian and Vietnamese representatives met in Phnom Penh in order to establish a commission to resolve border disagreements. The Vietnamese refused to recognize the Brévié Line—the colonial-era demarcation of maritime borders between the two countries—and the negotiations broke down. In late September, however, a few days before Pol Pot was forced to resign as prime minister, air links were established between Phnom Penh and Hanoi.

With Pol Pot back at the forefront of the regime in 1977, the situation rapidly deteriorated. Incidents escalated along all of Cambodia's borders. Khmer Rouge forces attacked villages in the border areas of Thailand near Aranyaprathet. Brutal murders of Thai villagers, including women and children, were the first widely reported concrete evidence of Khmer Rouge atrocities. There were also incidents along the Laos border.

At approximately the same time, villages in Vietnam's border areas underwent renewed attacks. In turn, Vietnam launched air strikes against Cambodia. From 18 to 30 April 1978, Cambodian troops, after invading the Vietnamese province of An Giang, carried out the Ba Chúc massacre causing 3,157 civilian deaths in the province of Tây Ninh, Vietnam. In September, border fighting resulted in as many as 1,000 Vietnamese civilian casualties. The following month, the Vietnamese counter-attacked in a campaign involving a force of 20,000 personnel.

Vietnamese defense minister General Võ Nguyên Giáp underestimated the tenacity of the Khmer Rouge, however, and was obliged to commit an additional 58,000 reinforcements in December. On 6 January 1978, Giap's forces began an orderly withdrawal from Cambodian territory. The Vietnamese apparently believed they had "taught a lesson" to the Cambodians, but Pol Pot proclaimed this a "victory" even greater than that of 17 April 1975. For several years, the Vietnamese government sought in vain to establish peaceful relations with the Khmer Rouge regime, but the Khmer Rouge leaders were intent on war. Behind this seeming insanity clearly lay the assumption that China would support the Khmer Rouge militarily in such a conflict.

Faced with growing Khmer Rouge belligerence, the Vietnamese leadership decided in early 1978 to support internal resistance to the Pol Pot regime, with the result that the Eastern Zone became a focus of insurrection. War hysteria reached bizarre levels within Democratic Kampuchea. In May 1978, on the eve of So Phim's Eastern Zone uprising, Radio Phnom Penh declared that if each Cambodian soldier killed thirty Vietnamese, only 2 million troops would be needed to eliminate the entire Vietnamese population of 50 million. It appears that the leadership in Phnom Penh was seized with immense territorial ambitions, i.e., to recover Kampuchea Krom, the Mekong Delta region, which they regarded as Khmer territory.

Massacres of ethnic Vietnamese and of their sympathizers by the Khmer Rouge intensified in the Eastern Zone after the May revolt. In November, Vorn Vet led an unsuccessful coup d'état. There were now tens of thousands of Cambodian and Vietnamese exiles on Vietnamese territory.

On 3 December 1978, Radio Hanoi announced the formation of the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation (KNUFNS). This was a heterogeneous group of communist and noncommunist exiles who shared an antipathy to the Pol Pot regime and a virtually total dependence on Vietnamese backing and protection. The KNUFNS provided the semblance, if not the reality, of legitimacy for Vietnam's invasion of Democratic Kampuchea and for its subsequent establishment of a satellite regime in Phnom Penh.

In the meantime, as 1978 wore on, Cambodian bellicosity in the border areas surpassed Hanoi's threshold of tolerance. Vietnamese policy makers opted for a military solution and, on 22 December, Vietnam launched its offensive with the intent of overthrowing Democratic Kampuchea. A force of 120,000, consisting of combined armor and infantry units with strong artillery support, drove west into the level countryside of Cambodia's southeastern provinces. Together, the Vietnamese army and the National Salvation Front struck at the Khmer Rouge on 25 December.

After a seventeen-day campaign, Phnom Penh fell to the advancing Vietnamese on 7 January 1979. Pol Pot and the main leaders initially took refuge near the border with Thailand. After making deals with several governments, they were able to use Thailand as a safe staging area for the construction and operation of new redoubts in the mountain and jungle fastness of Cambodia's periphery, Pol Pot and other Khmer Rouge leaders regrouped their units, issued a new call to arms, and reignited a stubborn insurgency against the regime in power as they had done in the late 1960s.

For the moment, however, the Vietnamese invasion had accomplished its purpose of deposing an unlamented and particularly violent dictatorship. A new administration of ex-Khmer Rouge fighters under the control of Hanoi was quickly established (who are ruling till present),[when?] and it set about competing, both domestically and internationally, with the Khmer Rouge as the legitimate government of Cambodia.

Peace still eluded the war-ravaged nation, however, and although the insurgency set in motion by the Khmer Rouge proved unable to topple the new Vietnamese-controlled regime in Phnom Penh, it did nonetheless keep the country in a permanent state of insecurity. The new administration was propped up by a substantial Vietnamese military force and civilian advisory effort.

As events in the 1980s progressed, the main preoccupations of the new regime were survival, restoring the economy, and combating the Khmer Rouge insurgency by military and by political means.

The Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea

[edit]The UN General Assembly voted by a margin of 71 to 35 for the Khmer Rouge to retain their seat at the UN, with 34 abstentions and 12 absentees.[82] The seat was occupied by Thiounn Prasith, an old cadre of Pol Pot and Ieng Sary from their student days in Paris and one of the 21 attendees at the 1960 KPRP Second Congress. The seat was retained under the name 'Democratic Kampuchea' until 1982 and then 'Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea' until 1993.

According to journalist Elizabeth Becker, former U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski said that in 1979, "I encouraged the Chinese to support Pol Pot. Pol Pot was an abomination. We could never support him, but China could.[83]" Brzezinski has denied this, writing that the Chinese were aiding Pol Pot "without any help or encouragement from the United States.[84]"

China, the U.S., and other Western countries opposed an expansion of Vietnamese and Soviet influence in Indochina, and refused to recognize the People's Republic of Kampuchea as the legitimate government of Cambodia, claiming that it was a puppet state propped up by Vietnamese forces. China funneled military aid to the Khmer Rouge, which in the 1980s proved to be the most capable insurgent force, while the U.S. publicly supported a non-Communist alternative to the PRK; in 1985, the Reagan administration approved $5 million in aid to the republican KPNLF, led by former prime minister Son Sann, and the ANS, the armed wing of the pro-Sihanouk FUNCINPEC party.

The KPNLF, while lacking in military strength compared to the Khmer Rouge, commanded a sizable civilian following (up to 250,000) amongst refugees near the Thai-Cambodian border that had fled the Khmer Rouge regime. Funcinpec had the benefit of traditional peasant Khmer loyalty to the crown and Sihanouk's widespread popularity in the countryside.

In practice, the military strength of the non-KR groups within Cambodia was minimal, though their funding and civilian support was often greater than the Khmer Rouge. The Thatcher and Reagan administrations both supported the non-KR insurgents covertly, with weapons, and military advisors in the form of Green Berets and Special Air Service units, who taught sabotage techniques in camps just inside Thailand.

The end of the CGDK and Khmer Rouge

[edit]A UN-led peacekeeping mission that took place from 1991 to 1995 sought to end violence in the country and establish a democratic system of government through new elections. The 1990s saw a marked decline in insurgent activity, though the Khmer Rouge later renewed their attacks against the government. As Vietnam disengaged from direct involvement in Cambodia, the government was able to begin to split the Khmer Rouge movement by making peace offers to lower level officials. The Khmer Rouge was the only member of the CGDK to continue fighting following the reconciliation process. The other two political organizations that made up the CGDK alliance ended armed resistance and became a part of the political process that began with elections in 1993.[85]

In 1997, Pol Pot ordered the execution of his right-hand man Son Sen for attempting peace negotiations with the Cambodian government. In 1998, Pol Pot himself died, and other key Khmer Rouge leaders Khieu Samphan and Ieng Sary surrendered to the government of Hun Sen in exchange for immunity from prosecution, leaving Ta Mok as the sole commander of the Khmer Rouge forces; he was detained in 1999 for "crimes against humanity." The organization essentially ceased to exist.

Recovery and trials

[edit]Since 1990 Cambodia has gradually recovered, demographically and economically, from the Khmer Rouge regime, although the psychological scars affect many Cambodian families and émigré communities. The current government teaches little about Khmer Rouge atrocities in schools. Cambodia has a very young population and by 2005 three-quarters of Cambodians were too young to remember the Khmer Rouge years. The younger generations would only know the Khmer Rouge through word-of-mouth from parents and elders.

In 1997, Cambodia established a Khmer Rouge Trial Task Force to create a legal and judicial structure to try the remaining leaders for war crimes and other crimes against humanity, but progress was slow, mainly because the Cambodian government of ex-Khmer Rouge Cadre Hun Sen, despite its origins in the Vietnamese-backed regime of the 1980s, was reluctant to bring the Khmer Rouge leaders to trial.

Funding shortfalls plagued the operation, and the government said that due to the poor economy and other financial commitments, it could afford only limited funding for the tribunal. Several countries, including India and Japan, came forward with extra funds, but by January 2006, the full balance of funding was not yet in place.

Nonetheless, the task force began its work and took possession of two buildings on the grounds of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF) High Command headquarters in Kandal province just on the outskirts of Phnom Penh. In March 2006 the Secretary General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan, nominated seven judges for a trial of the Khmer Rouge leaders.

In May 2006, Justice Minister Ang Vong Vathana announced that Cambodia's highest judicial body approved 30 Cambodian and U.N. judges to preside over the genocide tribunal for some surviving Khmer Rouge leaders. The chief Khmer Rouge torturer Kang Kek Iew – known as Duch and ex-commandant of the notorious S-21 prison – went on trial for crimes against humanity on 17 February 2009. It was the first case involving a senior Pol Pot cadre, three decades after the end of a regime blamed for 1.7 million deaths in Cambodia.[86]

Legacy

[edit]

The violent legacy of the Khmer Rouge regime and its aftermath continue to haunt Cambodia today. In recent years, increasing attention has been paid by the world to the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge, especially in light of the Cambodia Tribunal. In Cambodia, the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum and the Choeung Ek Killing Fields are two major sites open to the public which are preserved from the Khmer Rouge years and serve as sites of memory of the Cambodian genocide. The Tuol Sleng was a high school building that was transformed into an interrogation and torture centre called S-21 during the Khmer Rouge regime; today the site still contains many of the torture and prison cells which were created during the Khmer Rouge years. Choeng Ek was a mass grave site outside Phnom Penh where prisoners were taken to be killed; today the site is a memorial for those who died there.[citation needed]

However, beyond these two public sites, there has not been much activity promoted by the Cambodian government to remember the genocide that occurred. This, in part, is due to numerous Khmer Rouge cadres remaining in political power in the wake of the collapse of the Khmer Rouge regime. The continued influence of Khmer Rouge cadres in Cambodia's politics has led to a neglect of the teaching of Khmer Rouge history to Cambodian children. The lack of a strong mandate to teach Khmer Rouge history despite international pressure has led to a proliferation of literary and visual production to memorialise the genocide and create sites through which the past can be remembered by future generations.[citation needed]

In literature

[edit]The Cambodian genocide has spawned a host of literary publications in the wake of the Khmer Rouge regime's fall. Most significant to the history of the Khmer Rouge are the numerous survivor memoirs published in English as a way to remember the past. The first wave of Khmer Rouge memoirs began appearing in the late 1970s and 1980s. Soon after the first wave of survivors escaped or were rescued from Cambodia, survivor accounts in English and French began to be published.[citation needed]

Written to generate more awareness about the Khmer Rouge regime, these adult memoirs take into account the political climate in Cambodia before the regime and tend to call for justice to be served to the perpetrators of the regime. Being the first survivor accounts to reach global audiences, memoirs such as Haing Ngor's A Cambodian Odyssey (published 1987), Pin Yathay's L'Utopie meurtrière (Murderous Utopia) (1979), Laurence Picq's Au-delà du ciel (Beyond the Horizon) (1984) and Francois Ponchaud's Cambodge, annee zero (Cambodia Year Zero) (1977) were instrumental in bringing to the world the story of life under the Khmer Rouge regime.

The second wave of memoirs, published in the 21st century, include Chanrithy Him's When Broken Glass Floats (published 2000), Loung Ung's First They Killed My Father (2000), Oni Vitandham's On the Wings of a White Horse (2005) and Kilong Ung's Golden Leaf (2009). Published in large part by Cambodian survivors who were children during the period, these memoirs trace their journey from a war-torn Cambodia to their new lives in other parts of the world.[citation needed]

To a larger extent than memoirs from the first wave, these memoirs reconstruct the significance of their authors' experiences before they left Cambodia. Having grown up away from Cambodia, these individuals use their memoirs predominantly as a platform to come to terms with their lost childhood years, reconnect with their cultural roots which they cannot forget despite residing outside of Cambodia and tell this story for their children.[citation needed]

Noticeably, many of the authors of second wave memoirs draw out extended family trees in the beginning of their accounts in an attempt to document their family history. Additionally, some authors also note that despite them remembering events vividly, their memories were augmented by their relatives recounting those events to them as they grew up. Most significantly, the publication of the second wave of memoirs coincides with the Cambodia Tribunal and could be a response to the increased international attention paid to the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge.[citation needed]

In media

[edit]As in literature, there has been a proliferation of films on the Cambodian genocide. Most of the films are produced in documentary style, frequently with the aim to reveal what really happened during the Khmer Rouge years and to memorialise those who lived through the genocide. Film director Rithy Panh is a survivor of the Khmer Rouge's killing fields and is the most prolific producer of documentaries on the Khmer Rouge years. He has produced Cambodia: Between War and Peace and The Land of the Wandering Souls among other documentary films.[citation needed]

In S-21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine, two survivors of S-21 confront their former captors. In 2013, Panh released another documentary about the Khmer Rouge years titled The Missing Picture. The film uses clay figures and archival footage to re-create the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge regime. Beyond Panh, many other individuals (both Cambodians and non-Cambodians) have made films about the Khmer Rouge years. Year Zero: The Silent Death of Cambodia is a British documentary directed by David Munro in 1979 which managed to raise 45 million pounds for Cambodians.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Cambodia portal

- Communism portal

- Agrarian socialism

- First Indochina War

- List of socialist states

- Vietnam War (Second Indochina War)

- Cambodian genocide denial

- Mass killings under communist regimes

- First They Killed My Father (film)

- The Killing Fields (film)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Khmer: កម្ពុជាប្រជាធិបតេយ្យ, UNGEGN: Kâmpŭchéa Prâchéathĭbâtéyy [kampuciə prɑːciətʰipataj]

References

[edit]- ^ "Cambodia – Religion". Britannica. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Jackson, Karl D. (1989). Cambodia, 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death. Princeton University Press. p. 219. ISBN 0-691-02541-X.

- ^ "Khmer Rouge's Slaughter in Cambodia Is Ruled a Genocide". The New York Times. 15 November 2018. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ Kiernan, B. (2004) How Pol Pot came to Power. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. xix

- ^ "Cambodia – COALITION GOVERNMENT OF DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ a b Farley, Chris (1997). "The Pol Pot Regime: race, power and genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–79 By BEN KIERNAN (New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1996) 477pp. £25.00". Race & Class. 38 (4): 108–110. doi:10.1177/030639689703800410. ISSN 0306-3968. S2CID 144098516.

- ^ "Cambodians Designate Sihanouk as Chief for Life". The New York Times. UPI. 26 April 1975. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ "PHNOM PENH SAYS SIHANOUK RESIGNS". The New York Times. UPI. 5 April 1976. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ Osborne, Milton E. (1994). Sihanouk : prince of light, prince of darkness. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1638-2. OCLC 29548414.

- ^ "Khmer Rouge | Killing Fields | Pol Pot | Ieng Sary | Nuon Chea – Cambodian Information Center". 28 February 2010. Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ "A brief history of the Khmer Rouge". Archived from the original on 21 February 2009.

- ^ Short 2004, p. 273.

- ^ Short 2004, p. 287.

- ^ Elizabeth J. Harris (31 December 2017), "8. Cambodian Buddhism after the Khmer Rouge", Cambodian Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 190–224, doi:10.1515/9780824861766-009, ISBN 978-0-8248-6176-6

- ^ Tyner, James A. (2008). The killing of Cambodia: geography, genocide and the unmaking of space. Aldershot, England: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-7096-4. OCLC 183179515.

- ^ Vickery, Michael (1984). Cambodia, 1975–1982. Boston: South End Press. ISBN 0-89608-189-3. OCLC 10560044.

- ^ "Cartwright, Hon. Dame Silvia (Rose)", Cartwright, Hon. Dame Silvia (Rose), (Born 7 Nov. 1943), Governor-General of New Zealand, 2001–06; Trial Chamber Judge, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, 2006–14, Who's Who, Oxford University Press, 1 December 2007, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u10356

- ^ a b Becker, Elizabeth (1986). When the war was over: the voices of Cambodia's revolution and its people. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-41787-8. OCLC 13334079.

- ^ a b Jackson, Karl D., ed. (31 December 2014), "Bibliography", Cambodia, 1975–1978, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 315–324, doi:10.1515/9781400851706.315, ISBN 978-1-4008-5170-6, retrieved 3 October 2020

- ^ a b c Short 2004, p. 292.

- ^ a b Short 2004, p. 326.

- ^ Short 2004, pp. 323–24.

- ^ Short 2004, p. 319.

- ^ Short 2004, pp. 324–25.

- ^ "FREEDOM VIRTUALLY ENDS GENOCIDE AND MASS MURDER". www.hawaii.edu. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ Short 2004, pp. 345–46.

- ^ Short 2004, p. 349.

- ^ Short 2004, p. 346.

- ^ Jones, Adam (2006). Genocide A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. p. 192. ISBN 0-415-35384-X.

- ^ Etcheson, Craig (November 1990). "The Khmer Way Of Exile: Lessons From Three Indochinese Wars". Coastal Carolina University.

- ^ a b c "The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–79". The SHAFR Guide Online. doi:10.1163/2468-1733_shafr_sim240100033. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Short 2004, p. 313.

- ^ Short 2004, p. 293.

- ^ a b c Gellately, Robert; Kiernan, Ben, eds. (7 July 2003). The Specter of Genocide. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511819674. ISBN 978-0-521-52750-7.

- ^ a b c Pike, Douglas; Kiernan, Ben (1997). "Reviewed Work: The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–79 by Ben Kiernan". Political Science Quarterly (Review). 112 (2): 349. doi:10.2307/2657976. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2657976.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hinton, Alexander Laban (6 December 2004). Why Did They Kill? Cambodia in the Shadow of Genocide. University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520937949. ISBN 978-0-520-93794-9. S2CID 227214146.

- ^ Tkachenko, Maryna (8 May 2019). "Breaking Decades of Silence: Sexual Violence During the Khmer Rouge - Global Justice Center". globaljusticecenter.net. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Chandler 1992, pp. 130, 133; Short 2004, p. 358.

- ^ "Cambodia's brutal Khmer Rouge regime". 19 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ A History of Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1979). Documentation Center of Cambodia. 2007. p. 74. ISBN 978-99950-60-04-6.

- ^ Chandler 1992, p. 134; Short 2004, p. 367.

- ^ Short 2004, p. 364.

- ^ Landsiedel, Peter, "The Killing Fields: Genocide in Cambodia", ‘'P&E World Tour'’, 27 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2019

- ^ Frieson, Kate (1988). "The Political Nature of Democratic Kampuchea". Pacific Affairs. 61 (3): 419–421. doi:10.2307/2760458. ISSN 0030-851X. JSTOR 2760458. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ Jackson, Karl D. (1 January 1978). "Cambodia 1977: Gone to Pot". Asian Survey. 18 (1): 76–90. doi:10.2307/2643186. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2643186.

- ^ Ciorciari 2014, p. 217.

- ^ Ciorciari 2014, p. 215.

- ^ Short 2004, p. 300; Ciorciari 2014, p. 220.

- ^ Levin, Dan (30 March 2015). "China Is Urged to Confront Its Own History". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Kiernan, Ben (2008). The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia Under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–79. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14299-0.

- ^ Laura, Southgate (2019). ASEAN Resistance to Sovereignty Violation: Interests, Balancing and the Role of the Vanguard State. Policy Press. ISBN 978-1-5292-0221-2.

- ^ Ciorciari 2014, pp. 216–17.

- ^ Ciorciari 2014, p. 221.

- ^ Chandler 1992, p. 128; Short 2004, p. 361.

- ^ Short 2004, p. 362.

- ^ Short 2004, p. 363.

- ^ Solomon Kane (trad. de l'anglais par François Gerles, préf. David Chandler), Dictionnaire des Khmers rouges, IRASEC, février 2007, 460 p. (ISBN 978-2-916063-27-0)

- ^ Visites guidées au Kampuchéa Démocratique (1975–1978) – Marie Aberdam. Dans Relations internationales 2015/2 (n° 162), pages 139 à 15

- ^ Short 2004, p. 332.

- ^ Short 2004, pp. 332–33.

- ^ Jackson, Karl D., ed. (1989). Cambodia, 1975–1978: rendezvous with death. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-07807-6. OCLC 18739271.

- ^ Kuper, Leo; Staub, Ervin (1 September 1990). "The Roots of Evil: The Origins of Genocide and Other Group Violence". Contemporary Sociology. 19 (5): 683. doi:10.2307/2072322. ISSN 0094-3061. JSTOR 2072322.

- ^ Burton, Charles; Chandler, David P.; Kiernan, Ben (1984). "Revolution and Its Aftermath in Kampuchea". Pacific Affairs. 57 (3): 532. doi:10.2307/2759110. ISSN 0030-851X. JSTOR 2759110.

- ^ Farley, Chris (1 April 1997). "The Pol Pot Regime: race, power and genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–79 By BEN KIERNAN (New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1996) 477pp. £25.00". Race & Class. 38 (4): 108–110. doi:10.1177/030639689703800410. ISSN 0306-3968. S2CID 144098516.

- ^ a b Jackson, Karl D., ed. (31 December 2014), "Bibliography", Cambodia, 1975-1978, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 315–324, doi:10.1515/9781400851706.315, ISBN 978-1-4008-5170-6

- ^ Etcheson, Craig (11 July 2019). The Rise and Demise of Democratic Kampuchea. doi:10.4324/9780429314292. ISBN 978-0-429-31429-2. S2CID 242004655.

- ^ Chandler, David (1 February 2014). "Buddhism in a Dark Age: Cambodian Monks under Pol Pot. By Ian Harris. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2013. 242 pp. $22.00 (paper). – Pourquoi les Khmers Rouges [Why the Khmer Rouge]. By Henri Locard. Paris: Éditions Vendémiaire, 2013. 343 pp. €20.00 (paper). – The Elimination: A Survivor of the Khmer Rouge Confronts His Past and the Commandant of the Killing Fields. By Rithy Panh with Christophe Bataille. New York: Other Press, 2012. 271 pp. $22.95 (cloth)". The Journal of Asian Studies. 73 (1): 286–288. doi:10.1017/s0021911813002295. ISSN 0021-9118.

- ^ Summers, Laura (1 September 1985). "Book Review: Michael Vickery, Cambodia: 1975-1982 (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1984, 361 pp., £7.95 pbk.)". Millennium: Journal of International Studies. 14 (2): 253–254. doi:10.1177/03058298850140020921. ISSN 0305-8298. S2CID 144950123.

- ^ "Failure Through Neglect: The Women's Policies of the Khmer Rouge in Comparative Perspective" (PDF). 26 July 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Valentino, Benjamin A., 1971– (2004). Final solutions : mass killing and genocide in the twentieth century. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-6717-2. OCLC 828736634.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "State Violence in Democratic Kampuchea (1975–1979) and Retribution (1979–2004)" (PDF). 30 October 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Robins, Nicholas A.; Jones, Adam (25 April 2016). Genocides by the Oppressed: Subaltern Genocide in Theory and Practice – Nicholas A. Robins, Adam Jones – Google Books. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-22077-6. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Hinton, Alexander Laban (1 August 1998). "A Head for an Eye: Revenge in the Cambodian Genocide". American Ethnologist. 25 (3): 352–377. doi:10.1525/ae.1998.25.3.352. ISSN 0094-0496.

- ^ Robins, Nicholas A.; Jones, Adam (27 April 2016). Genocides by the Oppressed: Subaltern Genocide in Theory and Practice – Nicholas A. Robins, Adam Jones – Google Books. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-22077-6. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Fein, Helen (1 October 1993). "Revolutionary and Antirevolutionary Genocides: A Comparison of State Murders in Democratic Kampuchea, 1975 to 1979, and in Indonesia, 1965 to 1966". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 35 (4): 796–823. doi:10.1017/s0010417500018715. ISSN 0010-4175. S2CID 145561816.

- ^ "Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam)". 28 July 2011. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Cambodian Genocide Program | Yale University". 16 September 2013. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Counting Hell: The Death Toll of the Khmer Rouge Regime in Cambodia". 15 November 2013. Archived from the original on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ suckhoedoisong.vn (9 January 2009). ""Nếu không có bộ đội tình nguyện Việt Nam, sẽ không có điều kỳ diệu ấy"". suckhoedoisong.vn (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Không tìm thấy nội dung!". www.cpv.org.vn. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ Chandler 1992, p. 110; Short 2004, pp. 296–98.