Q.E.D.

Q.E.D. or QED is an initialism of the Latin phrase quod erat demonstrandum, meaning "that which was to be demonstrated". Literally, it states "what was to be shown".[1] Traditionally, the abbreviation is placed at the end of mathematical proofs and philosophical arguments in print publications, to indicate that the proof or the argument is complete.

Etymology and early use

[edit]The phrase quod erat demonstrandum is a translation into Latin from the Greek ὅπερ ἔδει δεῖξαι (hoper edei deixai; abbreviated as ΟΕΔ). The meaning of the Latin phrase is "that [thing] which was to be demonstrated" (with demonstrandum in the gerundive). However, translating the Greek phrase ὅπερ ἔδει δεῖξαι can produce a slightly different meaning. In particular, since the verb "δείκνυμι" means both to show or to prove,[2] a different translation from the Greek phrase would read "The very thing it was required to have shown."[3]

The Greek phrase was used by many early Greek mathematicians, including Euclid[4] and Archimedes.

The Latin phrase is attested in a 1501 Euclid translation of Giorgio Valla.[5] Its abbreviation q.e.d. is used once in 1598 by Johannes Praetorius,[6] more in 1643 by Anton Deusing,[7] extensively in 1655 by Isaac Barrow in the form Q.E.D.,[8] and subsequently by many post-Renaissance mathematicians and philosophers.[9]

Modern philosophy

[edit]

During the European Renaissance, scholars often wrote in Latin, and phrases such as Q.E.D. were often used to conclude proofs.

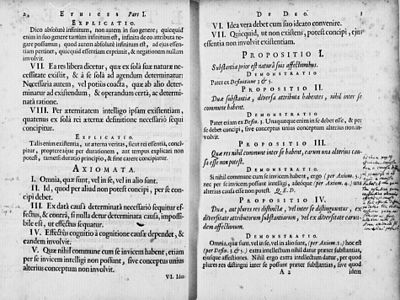

Perhaps the most famous use of Q.E.D. in a philosophical argument is found in the Ethics of Baruch Spinoza, published posthumously in 1677.[11] Written in Latin, it is considered by many to be Spinoza's magnum opus. The style and system of the book are, as Spinoza says, "demonstrated in geometrical order", with axioms and definitions followed by propositions. For Spinoza, this is a considerable improvement over René Descartes's writing style in the Meditations, which follows the form of a diary.[12]

Difference from Q.E.F.

[edit]There is another Latin phrase with a slightly different meaning, usually shortened similarly, but being less common in use. Quod erat faciendum, originating from the Greek geometers' closing ὅπερ ἔδει ποιῆσαι (hoper edei poiēsai), meaning "which had to be done".[13] Because of the difference in meaning, the two phrases should not be confused.

Euclid used the Greek original of Quod Erat Faciendum (Q.E.F.) to close propositions that were not proofs of theorems, but constructions of geometric objects.[14] For example, Euclid's first proposition showing how to construct an equilateral triangle, given one side, is concluded this way.[15]

Equivalent forms

[edit]

There is no common formal English equivalent, although the end of a proof may be announced with a simple statement such as "thus it is proved", "this completes the proof", "as required", "as desired", "as expected", "hence proved", "ergo", "so correct", or other similar phrases.

Typographical forms used symbolically

[edit]Due to the paramount importance of proofs in mathematics, mathematicians since the time of Euclid have developed conventions to demarcate the beginning and end of proofs. In printed English language texts, the formal statements of theorems, lemmas, and propositions are set in italics by tradition. The beginning of a proof usually follows immediately thereafter, and is indicated by the word "proof" in boldface or italics. On the other hand, several symbolic conventions exist to indicate the end of a proof.

While some authors still use the classical abbreviation, Q.E.D., it is relatively uncommon in modern mathematical texts. Paul Halmos claims to have pioneered the use of a solid black square (or rectangle) at the end of a proof as a Q.E.D. symbol,[16] a practice which has become standard, although not universal. Halmos noted that he adopted this use of a symbol from magazine typography customs in which simple geometric shapes had been used to indicate the end of an article, so-called end marks.[17][18] This symbol was later called the tombstone, the Halmos symbol, or even a halmos by mathematicians. Often the Halmos symbol is drawn on chalkboard to signal the end of a proof during a lecture, although this practice is not so common as its use in printed text.

The tombstone symbol appears in TeX as the character (filled square, \blacksquare) and sometimes, as a (hollow square, \square or \Box).[19] In the AMS Theorem Environment for LaTeX, the hollow square is the default end-of-proof symbol. Unicode explicitly provides the "end of proof" character, U+220E (∎). Some authors use other Unicode symbols to note the end of a proof, including, ▮ (U+25AE, a black vertical rectangle), and ‣ (U+2023, a triangular bullet). Other authors have adopted two forward slashes (//, ) or four forward slashes (////, ).[20] In other cases, authors have elected to segregate proofs typographically—by displaying them as indented blocks.[21]

Modern "humorous" use

[edit]In Joseph Heller's 1961 novel Catch-22, the Chaplain, having been told to examine a forged letter allegedly signed by him (which he knew he didn't sign), verified that his name was in fact there. His investigator replied, "Then you wrote it. Q.E.D." The chaplain said he did not write it and that it was not his handwriting, to which the investigator replied, "Then you signed your name in somebody else's handwriting again."[22]

See also

[edit]- List of Latin abbreviations

- A priori and a posteriori

- Bob's your uncle

- Ipso facto

- Q.E.A.

- List of Latin phrases (E) § ergo

References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of QUOD ERAT DEMONSTRANDUM". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2017-09-03.

- ^ Entry δείκνυμι at LSJ.

- ^ Euclid's Elements translated from Greek by Thomas L. Heath. 2003 Green Lion Press pg. xxiv

- ^ Elements 2.5 by Euclid (ed. J. L. Heiberg), retrieved 16 July 2005

- ^ Valla, Giorgio. "Georgii Vallae Placentini viri clariss. De expetendis, et fugiendis rebus opus. 1".

- ^ Praetorius, Johannes. "Ioannis Praetorii Ioachimici Problema, quod iubet ex Quatuor rectis lineis datis quadrilaterum fieri, quod sit in Circulo".

- ^ Deusing, Anton. "Antonii Deusingii Med. ac Philos. De Vero Systemate Mundi Dissertatio Mathematica : Quâ Copernici Systema Mundi reformatur: Sublatis interim infinitis penè orbibus, quibus in Systemate Ptolemaico humana mens distrahitur".

- ^ Barrow, Isaac. "Elementa geometrie : libri XV".

- ^ "Earliest Known Uses of some of the Words of Mathematics (Q)". jeff560.tripod.com. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ Philippe van Lansberge (1604). Triangulorum Geometriæ. Apud Zachariam Roman. pp. 1–5.

quod-erat-demonstrandum 0-1700.

- ^ "Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) – Modern Philosophy". opentextbc.ca. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ The Chief Works of Benedict De Spinoza, translated by R. H. M. Elwes, 1951. ISBN 0-486-20250-X.

- ^ Gauss, Carl Friedrich; Waterhouse, William C. (7 February 2018). Disquisitiones Arithmeticae. Springer. ISBN 9781493975600.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Q.E.F." mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ "Euclid's Elements, Book I, Proposition 1". mathcs.clarku.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ This (generally accepted) claim was made in Halmos's autobiography, I Want to Be a Mathematician. The first usage of the solid black rectangle as an end-of-proof symbol appears to be in Halmos's Measure Theory (1950). The intended meaning of the symbol is explicitly given in the preface.

- ^ Halmos, Paul R. (1985). I Want to Be a Mathematician: An Automathography. Springer. p. 403. ISBN 9781461210849.

- ^ Felici, James (2003). "The complete manual of typography : a guide to setting perfect type". Berkeley, CA : Peachpit Press.

- ^ See, for example, list of mathematical symbols for more.

- ^ Rudin, Walter (1987). Real and Complex Analysis. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-100276-6.

- ^ Rudin, Walter (1976). Principles of Mathematical Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-054235-X.

- ^ Heller, Joseph (1971). Catch-22. S. French. ISBN 978-0-573-60685-4. Retrieved 15 July 2011.