Roopmati

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

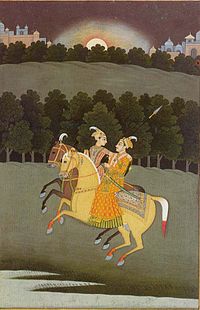

Rani Roopmati (kavi roopmati) was a Poet queen of Mandu and the consort of the Sultan of Malwa, Baz Bahadur.[1][2][3] Roopmati features prominently in the folklores of Malwa, which often describe the romance of the Sultan and his consort.[4][5]

According to folklore, Adham Khan was prompted to conquer Mandu partly due to Roopmati's beauty.[6] When Adham Khan marched on the sultan's fort, Baz Bahadur and a small force met him and were defeated. Bahadur fled, after which Roopmati, believing he was dead, and unwilling to submit to Adham Khan, poisoned herself.[7][8][9]

Life

[edit]

Baz Bahadur, ever so fond of music, was the last independent ruler of Mandu. Once out hunting, Baz Bahadur chanced upon a shepherdess frolicking and singing with her friends. Smitten by both her enchanting beauty and her melodious voice, he begged Roopmati to accompany him to his capital. Roopmati agreed to go to Mandu on the condition that she would live in a palace within sight of her beloved and venerated river, Narmada. Thus was built the Rewa Kund at Mandu.

Mughal Akbar decided to conquer Mandu. Akbar sent Adham Khan to capture Mandu and Baz bahadur went to challenge him with his small army. No match for the great Mughal army, Mandu fell easily.

Baz Bahadur fled to Chittorgarh to seek help. As Adham Khan came to Mandu, he was surprised by the beauty of Roopmati. Rani Roopmati stoically poisoned herself to avoid capture, bringing an end to the love story.[10]

Poems by Rani Roopmati

[edit]In 1599, Ahmad-ul-Umri Turkoman, who was in the service of Sharaf-ud-Din Mirza wrote the story of Rani Roopmati in Persian. He collected 26 poems of her and included them in his work. The original manuscript passed to his grandson Fulad Khan and his friend Mir Jafar Ali made a copy of the manuscript in 1653. Mir Jafar Ali's copy ultimately passed to Mehbub Ali of Delhi and after his death in 1831 passed to a lady of Delhi. Jemadar Inayat Ali of Bhopal brought this manuscript from her to Agra. This manuscript later reached C.E. Luard and translated into English by L.M. Crump under the title, The Lady of the Lotus: Rupmati, Queen of Mandu: A Strange Tale of Faithfulness in 1926. This manuscript has a collection of twelve dohas, ten kavitas and three sawaiyas of Rupmati.[11]

Rewa Kund and Rani Roopmati pavilion

[edit]The Rewa Kund is a reservoir built by Baz Bahadur at Mandu, equipped with an aqueduct to supply Roopmati's palace with water. Today, the site is revered as a holy spot. Baz Bahadur's Palace was constructed in the early 16th century, and is notable for its spacious courtyard fringed with halls, and high terraces which give a terrific view of the lovely surroundings. Rani Roopmati's Pavilion was built as an army observation post. It served a more romantic purpose as Roopmati's retreat. From this picturesque pavilion perched on a hilltop, the queen could gaze at her paramour's palace, and also at the Narmada flowing by, below. Rani Roopmati's double pavilion perched on the southern embattlements afforded a view of the Narmada valley.

-

Rani Roopmati pavilion

-

Baz Bahadur's palace

-

Rewa Kund

-

A mesmerising sunset at Rani Roopmati Pavilion

In popular culture

[edit]The story of Queen Roopmati has been adapted into several films in India, including: Rani Rupmati (1931) by Bhalji Pendharkar and Rani Rupmati (1959) by S.N. Tripathi starring Nirupa Roy in the titular role.[12] Kuldip Kaur played the role of the queen, portrayed as a dacoit, in the 1952 Indian film Baiju Bawra about the titular poet during the Mughal period.[13]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Safvi, Rana (14 October 2017). "For the queen of Malwa, with love". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ Jayamanne, Laleen (March 2013). "To sing and to dance, to think and to fight: an actor's second nervous system". Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 14 (1): 26–43. doi:10.1080/14649373.2013.745970. ISSN 1464-9373. S2CID 143526197.

- ^ Gupta, Subhadra Sen (20 October 2019). MAHAL: Power and Pageantry in the Mughal Harem. Hachette India. ISBN 978-93-88322-55-3.

- ^ Schofield, Katherine Butler (April 2012). "The Courtesan Tale: Female Musicians and Dancers in Mughal Historical Chronicles, c .1556–1748". Gender & History. 24 (1): 150–171. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0424.2011.01673.x. ISSN 0953-5233. S2CID 161453756.

- ^ Gupta, Archana Garodia (20 April 2019). The Women Who Ruled India: Leaders. Warriors. Icons. Hachette India. ISBN 978-93-5195-153-7.

- ^ Talbot, Cynthia (July 2018). "A Poetic Record of the Rajput Rebellion, c. 1680". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 28 (3): 461–483. doi:10.1017/S135618631800007X. ISSN 1356-1863. S2CID 165460715.

- ^ Mayer, Adrian C. (1960). Caste and Kinship in Central India. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-00835-9.

- ^ Podder, Tanushree (2005). Nur Jahan's Daughter. Rupa & Company. ISBN 978-81-291-0722-0.

- ^ Keene, Henry George (1885). A Sketch of the History of Hindustán from the First Muslim Conquest to the Fall of the Mughol Empire. W.H. Allen & Company.

- ^ "Rewa kund". Archived from the original on 14 March 2006. Retrieved 20 June 2006.

- ^ Khare, M.D. (ed.) (1981). Malwa through the Ages, Bhopal: Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Government of M.P., pp.365-7

- ^ Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema. British Film Institute. ISBN 9780851706696. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ Ayaz, Shaikh (18 April 2012). "Sixty Years of Baiju Bawra". openthemagazine.com. Open Media Network Pvt. Ltd. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]- Explore India: The Official Newsletter of the Ministry of Tourism. Durga Das Publications Pvt. Limited. 2001.

- Amiteshwar Ratra (2006). Marriage and Family: In Diverse and Changing Scenario. Deep & Deep Publications. ISBN 978-81-7629-758-5.

- M. D. Khare (1981). Malwa Through the Ages: Papers of the Seminar Held at Indore Museum on 7, 8, and 9 February, 1981. Directorate of Archaeology & Museums, Government of M.P.

- Seema Suneel (1995). Man-woman relationship in Indian fiction: with a focus on Shashi Deshpande, Rajendra Awasthy, and Syed Abdul Malik. Prestige Books. ISBN 9788185218984.

- Sir Thomas Herbert; John Anthony Butler (2012). Sir Thomas Herbert, Bart: Travels in Africa, Persia, and Asia the Great : Some Years Travels Into Africa and Asia the Great, Especially Describing the Famous Empires of Persia and Hindustan, as Also Divers Other Kingdoms in the Oriental Indies, 1627-30, the 1677 Version. ACMRS (Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies). ISBN 978-0-86698-475-1.

- Tiwari, Chandra Kant (1977). "Rupmati 'The Melody Queen of Malwa'". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 38: 244–249. JSTOR 44139077.

- "Afghan architecture in sandstone". The Hindu. 11 May 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Chand, Sharmila (7 September 2018). "Monsoon in Mandu". India Today. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- "Mandu in Madhya Pradesh is a romantic treasure waiting to be explored". Times Travel. 18 September 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2019.