First Report on the Public Credit

First Report on the Public Credit

|

|---|

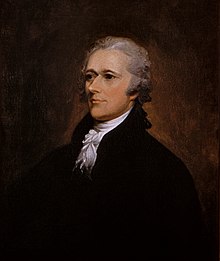

The First Report on the Public Credit was one of four major reports on fiscal and economic policy submitted by Founding Father and first US Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton on the request of Congress.[1] The report analyzed the financial standing of the United States and made recommendations to reorganize the national debt and to establish the public credit.[2] Commissioned by the US House of Representatives on September 21, 1789, the report was presented on January 9, 1790,[3] at the second session of the 1st US Congress.[4]

The 40,000-word document[5] called for full federal payment at face value to holders of government securities ("redemption") and the federal government to assume funding of all state debt ("assumption").[3] The political stalemate[6] in Congress that ensued led to the Compromise of 1790, which located the permanent US capital on the Potomac River ("residency").

The Federalists' success in winning approval for Hamilton's reforms led to the emergence of an opposition party, the Democratic-Republicans[7] and set the stage for political struggles that would persist for decades in American politics.[8]

Government debt under the Articles of Confederation

[edit]During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress, under the Articles of Confederation, amassed huge war debts but lacked the power to service these obligations by tariffs or other taxation.[9][10] As an expedient, the revolutionary government resorted to printing money and bills of credit,[3] but that currency rapidly underwent depreciation.[3][9] To avoid bankruptcy, the Continental Congress eliminated $195 million of its $200 million debt by fiat.[9][10] After the American Revolutionary War, the Continental currency, called "Continentals," would be deemed worthless.[3]

With its finances in disarray, the legislature abdicated its fiscal responsibilities by shifting them to the 13 states.[9] When the state legislatures failed to meet quotas for war material by local taxation, Patriot armies turned to confiscating supplies from farmers and tradesmen, compensating them with IOUs of uncertain value.[11] By the end of the war, over $90 million in state debt was outstanding.[12] Much of the state and national fiscal disorder, exacerbated by an economic crisis in urban commercial centers,[13] had remained unresolved when the Report was issued.[14]

Funding of national debt

[edit]With ratification of the US Constitution in 1787,[15] Congress could impose import duties and levy taxes for the raising of revenue to honor those financial obligations.[15][16]

The US national debt, according to the Report, included $40 million in domestic debt and $12 million in foreign debt, both of which were inherited from the Continental Congress.[17][18] In addition, the 13 states altogether owed $25 million from debts incurred during the American Revolution. The combined US debt, as calculated, stood at $77 million.[19][20]

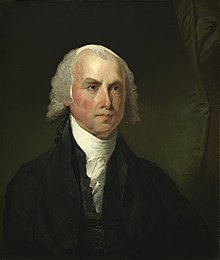

A consensus arose in Congress for the primary source of revenue to be tariff and tonnage duties,[21][22] which would serve to cover operating expenses for the central government and to pay interest and principal on foreign and domestic debt.[21] Under the guidance of US Representative James Madison, who led the House,[23] a tariff act was passed on July 4, 1789.[21][22]

Congress created the executive departments in September 1789, and Alexander Hamilton was confirmed by the Senate to regulate the powerful Treasury Department.[23][24] Madison, having "actively promoted" Hamilton's appointment,[25] was expected to co-operate in creating an energetic central government.[26]

Schemes to establish public credit: repudiation, discrimination, redemption

[edit]

With sources of revenue legislated, Congress proceeded to address the pressing issue of public credit.[27] Establishing government credit, the government's ability to borrow, was deemed a necessity if the nation was to endure.[10] To convince investors to purchase US securities, a system was needed for the reliable payment of interest.[10] Considering the magnitude of the debt burden that it had inherited,[28] Congress wished to dispose of it with economy,[10] and "the only real difference of opinion... was how much of the existing debt had to be redeemed in order to establish the government credit."[10]

Various plans had been considered to pay down the domestic debt under the new federal government.[29] Some advocates wanted to scale back the debt to ease tax burdens abruptly to retire the debt quickly. Proposals to default on the loans were termed partial or full "repudiation."[30] None of them, however, suggested defaulting on any portion of the $12 million foreign debt,[31] with $1.5 million in interest,[32] which was regarded as a "sacred obligation [to be] paid in full."[10]

A significant portion of the nation's $40 million domestic debt [20] was owed to Patriots who had supported the War of Independence by loans or personal service. Many of them were combat veterans who, during demobilization in 1783,[13] had been paid in IOUs, "certificates of indebtedness"[33] or "securities" (not to be confused with the worthless Continental currency or bills of credit)[3] and redeemable when the government's fiscal order had been restored.[34]

Schemes more in sympathy with the ex-soldiers who had relinquished their certificates to speculators at reduced rates were termed "discrimination" and called for paying the original holder of the security at full value and for reimbursing the current holder of the security at its purchase price. The combined payments would, however, exceed the denomination of the original certificate.[35]

US Representative James Madison of Virginia offered his own variation of "discrimination" that would preserved the federal obligation of face value debt repayment.[30] In his version, current certificate holders would be reimbursed at their purchase price for the devalued certificate, and the balance would be handed to the original holder. The government outlay would match the face value of the original certificate.[36]

Hamilton rejected both "repudiation" and "discrimination" and championed "redemption," the reserving of payment at full value strictly to the current holders of the certificates, with arrears of interest.[37]

Near the close of the first session of the 1st Congress in September 1789, with the matter of establishing public credit unresolved, the legislature directed the new Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, to prepare a report on credit.[38]

Political debate over Hamilton's "Redemption"

[edit]

Hamilton's First Report on the Public Credit was delivered to Congress on January 9, 1790. It called for payment in full on all government debts as the foundation for establishing government credit.[39] Hamilton argued that to be required for the creation of a favorable climate for investment in government securities and for the transformation of the public debt to a source of capital.[40] His model was the British financial system, which absolutely required fidelity to creditors.[41]

Before the government could resume borrowing,[10] Hamilton insisted for the $13 million in arrears of interest to be converted into principal, with payments at 4% on reissued securities.[42] The plan would be funded by pledging a portion of the government tariff and tonnage revenue irrevocably to the payment schedule.[43] Additionally, contracted debt would be serviced by sinking funds derived from postal service revenue that was earmarked for that purpose.

Rather than seeking to liquidate the national debt, Hamilton recommended for government securities to be traded at par to promote their exchange as legal tender equivalent in value to hard currency.[40] Regular payments of the public debt would allow Congress to increase federal money supply safely, which would stimulate capital investments in agriculture and manufacturing. With economic prosperity, the enterprises would more easily carry their tax burdens and provide the revenue to service the national debt.[44]

Monied speculators, alerted that Congress, under the new Constitution, might provide for payment at face value for certificates, sought to buy up devalued securities for profit and investment.[45] Concerns arose since many certificates, almost three quarters of them,[46] had been exchanged for well below par during periods of inflation,[34] some as low as 10 cents on the dollar,[47] but they sold at 20-25% while the Report was debated.[48]

When the report was made public in January 1790, speculators in Philadelphia and New York sent buyers by ship to southern states to buy up securities before the South became aware of the plan. Devalued certificates were relinquished by holders at low rates even after the news had been received, which reflected the widely held conviction in the South that the credit and assumption measures would be defeated in Congress. The value of government certificates continued to fall months after Hamilton's scheme was published, and "the sellers speculated upon the purchasers."[49]

US Representative James Madison led a vigorous opposition to Hamilton's "redemption"[30][50] but fully supported the development of good credit. In his address to the House on February 11, 1790, Madison characterized Hamilton's "redemption" as a formula to defraud "battle-worn veterans of the war for independence" [30] and a handout to well-to-do speculators, mostly rich Northerners, including some members of Congress.[51] Madison's "discrimination" promised to correct those abuses in the names of financial rectitude and natural justice.[36]

Introducing political rhetoric into the debate that resonated with his home state of Virginia,[52] Madison laid the groundwork for a national party for democrats.[53] His principled opposition to "redemption" was consistent with his view of a federal government designed to shield the less powerful from a majority interest, in this case his agrarian constituency, from Federalist-sponsored economic nationalism.[54]

The essence of Hamilton's economic position on "redemption" was that any compromise on the sanctity of promissory notes would undermine confidence in credit[55] and that concentrating capital into fewer hands would strengthen commercial investment and encourage constructive economic growth,[56] which would enlarge government credit available to business enterprises.[57]

As Hamilton's plan would greatly simplify and streamline finances, he found Madison's concern over the question of honoring both original and present holders of government securities naïve and counterproductive.[58]

Adopting a much-broader view of the effects of speculation, Hamilton acknowledged that many certificates had been obtained by wealthy individuals, but he considered the "few great fortunes" of minor significance and a "necessary evil" in the transition to sound credit.[59] His object was "to serve the nation, not to enrich a clique," and to establish faith in the national currency to avoid bankruptcy.[60] Ultimately, he wished to unleash the vast productive potential he perceived as part of America's destiny.[61]

In promoting the utility of his program, however, Hamilton had neglected to address popular perceptions of injustices to wartime patriots by postwar speculation.[62] The Federalists, yoking their political fortunes to the financial elites,[63] failed to cultivate their natural political base: "small businessmen and conservative farmers."[64] Hamilton confessed years later that "the Federalists have... erred in relying so much on the rectitude and utility of their measures, as to have neglected the cultivation of popular favor, by fair and justifiable expedients."[65]

Congress rejected Madison's "discrimination" in favor of Hamilton's "redemption" by 36 to 13 in the House of Representatives,[30] which preserved the sanctity of contracts as the cornerstone establishing confidence in public credit.[66] Madison's defeat, however, established his reputation "as a friend of the common man."[67]

Credit, private or public, is of greatest consequence to every country. Of this, it might be called the invigorating principle.

— Alexander Hamilton [29]

"Assumption:" shifting state debt to federal government

[edit]The key provision in Hamilton's fiscal reform was termed "assumption" and called for the 13 states to consolidate their outstanding debt of $25 million[68] and to transfer it to the federal government for servicing under a general funding plan.[69]

Hamilton's chief objectives were both economic and political.[36][70] Economically, state securities were vulnerable to local fluctuations in value and thus to speculative buying and selling, activities that would threaten the integrity of a national credit system.[71] Furthermore, with each state legislature formulating separate repayment plans, the federal government would be forced to compete with states for sources of tax revenue. Hamilton's "assumption" promised to obviate those conflicts.[72]

Politically, Hamilton sought to "tie the creditors to the new [central] government"[73] by linking their financial fortunes to the success of his economic nationalism.[74] That would, in turn, gradually cause a decline in state authority and a relative increase in federal influence.[50][75]

Agrarian opposition to "assumption"

[edit]Hamilton's funding scheme and "redemption" had won relatively quick approval,[76] but "assumption" was stalled by bitter resistance from southern legislators, led by James Madison.[77]

One of the effects of "assumption" would be to distribute the collective debt burden among all the states, the more solvent members paying a share of the more indebted ones.[78] Most of the southern states, except for South Carolina, had successfully paid down the bulk of their wartime debt.[79] Virginia, relatively debt-free, led the fight against 'assumption." Madison argued that the proposed national tax would overburden Virginia planters operating on a narrow margin of profit.[36][80] Requiring solvent states to contribute to states suspected of mismanaging their fiscal affairs was deemed unjust.[81]

Before any vote on "assumption," Madison insisted on a balancing of state accounts, termed "settlement," to determine the burden that each state would be compelled to contribute under the plan. He calculated that under Hamiliton's plan, Virginia would be responsible for providing $5 million in new federal revenue, but the federal government would assume only $3 million of Virginia's debt.[82]

In surrendering their debt into the hands of the Treasury Department, the states would sanction the principle of collective decision-making at the national level on state matters and "enormously strengthen" the influence of the federal government.[83] At the heart of the opposition lay a political fear of "consolidation," with power and wealth concentrated in fewer hands and the states "absorbed by the new federal government."[84]

Madison and his majority in the House blocked passage of the legislation on "assumption" in a test vote in April.[85] Subsequent votes ended in rejection and had brought "the business of Congress to a standstill" by June 1790.[86]

"Residency," "assumption," and "dinner-table bargain"

[edit]The US Constitution had provided for the establishment of a permanent "seat of government," a national capital, without designating a location.[87] New York City served as a temporary site to conduct federal affairs until a permanent "residence" could be agreed upon.[88] Intense Congressional debates arose over the "residency question" and resulted in proposals identifying 16 possible sites in competing states, none of which could muster majority support.[87][89] A number of government officials and state delegations gathered in clandestine meetings and political dinners[90] to resolve the stalled "assumption" bill by linking the "residency" debate to passage of Hamilton's financial program.[91]

Thomas Jefferson, who recently returned from France, where he had acted as a foreign diplomat, understood the practical necessity of Hamilton's fiscal goals establishing America's legitimacy throughout Europe's financial centers.[92] As the newly appointed Secretary of State, Jefferson invited Hamilton to meet privately with the opposition leader James Madison in an effort to broker a compromise on "assumption" and "residence."[93][94] The "dinner-party bargain"[95][96] made Madison withdraw his opposition and permit passage of the Assumption Bill.[97] For his part, Hamilton agreed to suppress opposition for the permanent location of the nation's capital at Georgetown on the Potomac, the present site of Washington, DC.[96][98] Hamilton's support was superfluous, as the Potomac location had already been secured.[95][99]

Jefferson and Madison acquiesced in the passage of "assumption" as an expedient to avoid government bankruptcy and disunion,[100][101] not because they condoned Hamilton's economic nationalism.[102] Jefferson's "dinner-party"[6] was in fact "the final chapter in an ongoing negotiation that [succeeded] because the ground had already been prepared"[99][103] and produced "the first great compromise of the new federal government."[102]

Jefferson and Madison extracted a major concession from Hamilton in the recalculation of Virginia's debt under the fiscal plan.[104] A zero-sum arrangement was contrived in which Virginia would pay $3.4 million to the federal government and receive exactly that amount in federal compensation.[99] The revision of Virginia 's debt, coupled with Potomac residence, ultimately netted it over $13 million.[105]

Indifferent to agrarian hostility to his economic proposals,[106] Hamilton had "[driven] into alliance two very different trends of opinion: the "gentlemen planters" cherished local autonomy and limited government enlisted the support of lower-middle class, and "artisans and western farmers" favored democratic government and majority rule.[107] Those forces, one with Republican commitments, the other with Democratic convictions, united in common cause against Hamilton's reforms and "laid the basis for a national party."[108]

The Residence Bill passed in the House by a vote of 32 to 29 on July 9, 1790, and the Assumption Bill cleared by a vote of 34 to 28 on July 26, 1790.[109]

Administration and performance

[edit]The adoption of Hamilton's report had the immediate effect of converting what had been virtually worthless federal and state certificates of indebtedness to $60 million of funded government securities.[110] The fully funded central government regained the ability to borrow and attracted foreign investment as social unrest destabilized Europe. In addition, the newly issued bonds provided a circulating currency and stimulated business investment.[110]

Hamilton submitted a schedule of excise taxes on December 13, 1790 [111] to augment revenue necessary to service debts assumed from the states.[112] The national debt reached $80 million and required nearly 80% of annual government expenditures. The interest alone on the national debt consumed 40% of the national revenue between 1790 and 1800.[56]

Hamilton was instrumental in setting up a national administration that would carry out those programs. Setting the highest possible standard, he has been called "one of the greatest administrators of all time."[113] He modernized performance in public office and personally oversaw the details of an increasingly complex system "without sacrificing dispatch, clarity or discipline."[113]

The Treasury Department quickly grew in stature and personnel, encompassing the United States Customs Service, the United States Revenue Cutter Service, and the network of Treasury agents that Hamilton had foreseen.[114] Hamilton immediately followed up his success with the Second Report on Public Credit, which contained his plan for the Bank of the United States, a national, privately operated bank endowed with public funds that became the forerunner of the Federal Reserve System. In 1791 Hamilton released a third report, the Report on Manufactures, which encouraged the growth and protection of manufacturing.

Hamilton's First Report on the Public Credit and his subsequent reports on a national bank and manufacturing stand as "the most important and influential state papers of their time and remain among the most brilliant government reports in American history."[115]

See also

[edit]- Second Report on Public Credit

- Report on Manufactures

- Political economy

- The Federalist Papers

- Report on a Plan for the Further Support of Public Credit

References

[edit]- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 40

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 91, Malone, 1960, p. 259 p. 259

- ^ a b c d e f Malone, 1960, p. 260

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 41, Smith, 1980, p. 147

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 60

- ^ a b Ellis, 2000, p. 50

- ^ Brock, 1959, p. 44, p. 45, Ellis, 2000, p. 80, Hofstadter, 1957, p. 14

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 41, Hofstadter, 1948, p. 14, Malone, 1960, p. 265

- ^ a b c d Staloff, 2005, p. 69

- ^ a b c d e f g h Miller, 1960, p. 37

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 69-70

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 70

- ^ a b Hofstadter, 1957, p. 125

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 61

- ^ a b Miller, 1960, p. 14

- ^ Malone, 1960, p. 256

- ^ Smith, 198, p. 147

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 91-92

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 92

- ^ a b Ellis, 2000, p. 55

- ^ a b c Miller, 1960, p. 15

- ^ a b Malone, 1957, p. 256

- ^ a b Miller, 1960, p. 33

- ^ Malone, 1957, p. 257

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 36

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 35

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 36-37, Malone, 1957, p. 259,

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 14, p. 38

- ^ a b Brock, 1957, p. 41

- ^ a b c d e Ellis, 2000, p. 56

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 41, Burstein, 2010, p. 214

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 38

- ^ Malone, 1960, p. 260, Brock, 1957, p. 41

- ^ a b Ellis, 2000, p. 55-56

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 41-42

- ^ a b c d Brock, 1957, p. 42

- ^ Malone, 1960, p. 259

- ^ Malone, 1957, p. 259, Miller, 1960, p. 39

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 39

- ^ a b Staloff, 2005, p. 93

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 40

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 92-93, Brock, 1957, p. 39

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 39-40

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 94

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 56, Brock, 1957, p. 42, Miller, 1960, p. 44

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 92-93

- ^ Burstein, 2010, p. 214

- ^ Malone, 1960, p. 260, Staloff, 2005, p. 92

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 44-45

- ^ a b Burstein, 2010, p. 214-215

- ^ Burstein, 2010, p. 214, Brock, 1957, p. 42, Miller, 1960, p. 42

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 45

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 46

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 46, Miller, 1960, p. 41,

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 42, Ellis, 2000, p. 62

- ^ a b Miller, 1960, p. 53

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 56, Miller, 1960, p. 41, Brock, 1957, p. 43

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 61, Miller, 1960, p. 41, Staloff, 2005, p. 95

- ^ Malone, 1960, p. 260, Brock, 1957, p. 43

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 43

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 52, Ellis, 2000, p. 61, p. 63, Staloff, 2005, p. 85, p. 86

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 61, Brock, 1957, p. 39 p. 41-42

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 64

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 44

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 39

- ^ Malone, 1960, p. 260, Staloff, 2005, p. 96, Miller, 1960, p. 43

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 43

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 55, Varon, 2008, p. 31,

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 55, Staloff, 2005, p. 92, p. 96

- ^ Miller, 1969, p. 39

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 42, Ellis, 2000, p. 57

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 92, p. 96

- ^ Smith, 1980, p. 147

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 42, Miller, 1960, Staloff, 2005, p. 96

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 41

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 96, p. 312

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 48

- ^ Smith, 1980, p. 148, Miller, 1960, p. 46

- ^ Malone, 1960, p. 260, Ellis, 2000, p. 57

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 65

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 42, Ellis, 2000, p. 57, Burstein & Isenberg, 2010, p. 216

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 58, Miller, 1960, p. 46-47

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 42, Ellis, 2000, p. 58, Burstein & Isenberg, 2010, p. 214-215

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 59

- ^ Malone, 1960, p. 261

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 312, Miller, 1960, p. 47

- ^ a b Ellis, 2000, p. 69

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 67

- ^ Malone, 1960, 261

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 48

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p.50,p 72

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 68

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 96, p. 313

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 48-49

- ^ a b Burstein & Isenberg, 2010, p. 218

- ^ a b Ellis, 2000, p. 49

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 49

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 313

- ^ a b c Ellis, 2000, p. 73

- ^ Varon, 2008, p. 31

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 50-51, p. 78

- ^ a b Staloff, 2005, p. 313

- ^ Burstein & Isenberg, 2010, p.218 - 219

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 96-97

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 96, p. 313, Ellis, 2000, p. 73-74

- ^ Brock, 1957, p. 42,

- ^ Hofstadter, 1948, p. 14-15

- ^ Malone, 1960, p. 260, Brock, 1957, p. 45, Staloff, 2005, p. 313

- ^ Ellis, 2000, p. 50, Smith, 1980, p. 154

- ^ a b Miller, 1960, p. 50

- ^ Staloff, 2006, p. 97

- ^ Miller, 1960, p. 155

- ^ a b Brock, 1959, p. 39

- ^ American Experience, hour 2American Experience

- ^ Staloff, 2005, p. 91, Miller, 1960, p. 63

Sources

[edit]- Bordewich, Fergus M. The First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government (2016) on 1789–91.

- Brock, W.R. 1957. The Ideas and Influence of Alexander Hamilton in Essays on the Early Republic: 1789-1815. Ed. Leonard W. Levy and Carl Siracusa. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974.

- Burstein, Andrew and Isenberg, Nancy. 2010. Madison and Jefferson. New York: Random House

- Chernow, Ron (2004). Alexander Hamilton. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 1-59420-009-2.

- Ellis, Joseph J. 2000. Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation., Alfred A. Knopf. New York. ISBN 0-375-40544-5

- Hofstadter, Richard. 1948. The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It. New York: A. A. Knopf.

- Malone, Dumas and Rauch, Basil. 1960. Empire for Liberty: The Genesis and Growth of the United States of America. Appleton-Century Crofts, Inc. New York.

- Miller, John C. 1960. The Federalists: 1789-1801. Harper & Row, New York. ISBN 9781577660316

- Staloff, Darren. 2005. Hamilton, Adams, Jefferson: The Politics of Enlightenment and the American Founding. Hill and Wang, New York. ISBN 0-8090-7784-1

External links

[edit]- Full text entitled "Report Relative to a Provision for the Support of Public Credit". Founders Online, National Archives and Records Administration (Accessed 2016-10-25).

- The original text from George Washington University

- Alexander Hamilton. PBS American Experience (2007-05-14).