Rhea (moon)

| |||||||||

| Discovery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | G. D. Cassini | ||||||||

| Discovery date | December 23, 1672 | ||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||

| Saturn V | |||||||||

| Adjectives | Rhean | ||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[1] | |||||||||

| 527 108 km | |||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.001 258 3 | ||||||||

| 4.518 212 d | |||||||||

| Inclination | 0.345° (to Saturn's equator) | ||||||||

| Satellite of | Saturn | ||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||

| Dimensions | 1532.4×1525.6×1524.4 km[2] | ||||||||

Mean radius | 763.8 ± 1.0 km[2] | ||||||||

| 7 337 000 km2 | |||||||||

| Mass | (2.306 518 ± 0.000 353)×1021 kg[3] (~3.9×10−4 Earths) | ||||||||

Mean density | 1.236 ± 0.005 g/cm3[2] | ||||||||

| 0.264 m/s2 | |||||||||

| 0.635 km/s | |||||||||

| 4.518 212 d (synchronous) | |||||||||

| zero | |||||||||

| Albedo | 0.949 ± 0.003 (geometric)[4] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| 10 [5] | |||||||||

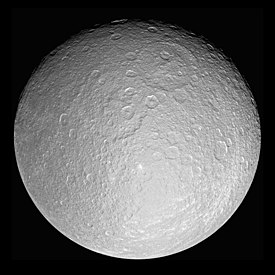

Rhea (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈriːə/;[note 1] Greek: Ῥέᾱ) is the second-largest moon of Saturn and the ninth largest moon in the Solar System. It was discovered in 1672 by Giovanni Domenico Cassini.

Name

Rhea is named after the Titan Rhea of Greek mythology, "mother of the gods". It is also designated Saturn V (being the fifth major moon going outward from the planet).

Cassini named the four moons he discovered (Tethys, Dione, Rhea and Iapetus) Sidera Lodoicea (the stars of Louis) to honor King Louis XIV. Astronomers fell into the habit of referring to them and Titan as Saturn I through Saturn V. Once Mimas and Enceladus were discovered, in 1789, the numbering scheme was extended to Saturn VII.

The names of all seven satellites of Saturn then known come from John Herschel (son of William Herschel, discoverer of the planet Uranus, and two other Cronian moons, Mimas and Enceladus) in his 1847 publication Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope, wherein he suggested the names of the Titans, sisters and brothers of Cronos (Saturn, in Roman mythology), be used.[6]

Physical characteristics

Size, mass and internal structure

Rhea is an icy body with a density of about 1.236 g/cm3. This low density indicates that it is made of ~25% rock (density ~3.25 g/cm3) and ~75% water ice (density ~0.93 g/cm3). While Rhea is the ninth-largest moon, it is only the tenth-most-massive moon.[note 2]

Earlier it was assumed that Rhea had a rocky core in the center.[7] However measurements taken during a close flyby by the Cassini orbiter in 2005 (see below) cast this into doubt, though this remains controversial. In a paper published in 2007 it was claimed that the axial dimensionless moment of inertia coefficient was 0.4.[note 3][8] Such a value indicated that Rhea had an almost homogeneous interior (with some compression of ice in the center) while the existence of a rocky core would imply a moment of inertia of about 0.34.[7] In the same year another paper claimed the momentum of inertia was about 0.37[note 4] implying that Rhea was partially differentiated.[9] A year later yet another paper claimed that the moon may not be in hydrostatic equilibrium meaning that the moment of inertia can not be determined from the gravity data alone.[10] In 2008 an author of the first paper tried to reconcile these three disparate results. He concluded that there is a systematic error in the Cassini radio Doppler data used in the analysis, but after restricting the analysis to a subset of data obtained closest to the moon, he arrived at his old result that Rhea was in hydrostatic equilibrium and had the moment inertia of about 0.4, again implying a homogeneous interior. Further measurements are necessary to resolve this problem.[11]

The triaxial shape of Rhea is consistent with a homogeneous body in hydrostatic equilibrium.[12]

Models suggest that Rhea could be capable of sustaining an internal liquid water ocean through heating by radioactive decay.[13]

Surface features

Rhea's features resemble those of Dione, with dissimilar leading and trailing hemispheres, suggesting similar composition and histories. The temperature on Rhea is 99 K (−174 °C) in direct sunlight and between 73 K (−200 °C) and 53 K (−220 °C) in the shade.

Rhea has a rather typical heavily cratered surface,[14] with the exceptions of a few large Dione-type fractures (whispy terrain) on the trailing hemisphere(the side facing away from the direction of motion along Rhea's orbit)[15] and a very faint "line" of material at Rhea's equator that may have been deposited by material deorbiting from its rings.[16] Rhea has two very large impact basins on its anti-Cronian hemisphere, which are about 400 and 500 km across.[15] The more northerly and less degraded of the two, called Tirawa, is roughly comparable to the basin Odysseus on Tethys.[14] There is a 48 km-diameter impact crater at 112°W that is prominent because of an extended system of bright rays.[15] This crater, called Inktomi, is nicknamed "The Splat", and may be one of the youngest craters on the inner moons of Saturn.[15] No evidence of any endogenic activity has been discovered.[15]

Its surface can be divided into two geologically different areas based on crater density; the first area contains craters which are larger than 40 km in diameter, whereas the second area, in parts of the polar and equatorial regions, has only craters under that size. This suggests that a major resurfacing event occurred some time during its formation. The leading hemisphere is heavily cratered and uniformly bright. As on Callisto, the craters lack the high relief features seen on the Moon and Mercury. On the trailing hemisphere there is a network of bright swaths on a dark background and few visible craters. It had been thought that these bright areas might be material ejected from ice volcanoes early in Rhea's history when its interior was still liquid. However, recent observations of Dione, which has an even darker trailing hemisphere and similar but more prominent bright streaks, show that the streaks are in fact ice cliffs resulting from extensive fracturing of the moon's surface. It is plausible that the bright streaks on the Rhean surface are also tectonically formed ice cliffs.

The January 17, 2006 distant flyby by the Cassini spacecraft yielded images of the wispy hemisphere at better resolution and a lower sun angle than previous observations. While scientific analysis is still pending, raw images from the flyby seem to show that Rhea's streaks in fact are ice cliffs similar to those of Dione.

Atmosphere

On November 27, 2010, NASA announced the discovery of a tenuous atmosphere—exosphere. It consists of oxygen and carbon dioxide in proportion of roughly 5 to 2. The surface density of the exosphere is from 105 to 106 molecules in a cubic centimeter depending on local temperature. The main source of oxygen is radiolysis of water ice at the surface by ions supplied by the magnetosphere of Saturn. The source of the carbon dioxide is less clear, but it may be related to oxidation of the organics present in ice or to outgassing of the moon's interior.[17][18]

Possible ring system

On March 6, 2008, NASA announced that Rhea may have a tenuous ring system. This would mark the first discovery of rings about a moon. The rings' existence was inferred by observed changes in the flow of electrons trapped by Saturn's magnetic field as Cassini passed by Rhea.[19][20][21] Dust and debris could extend out to Rhea's Hill sphere, but were thought to be denser nearer the moon, with three narrow rings of higher density. The case for a ring was strengthened by the subsequent finding of the presence of a set of small ultraviolet-bright spots distributed along Rhea's equator (interpreted as the impact points of deorbiting ring material).[22] However, when Cassini made targeted observations of the putative ring plane from several angles, no evidence of ring material was found, suggesting that another explanation for the earlier observations is needed.[23][24]

Exploration

The first images of Rhea were obtained by Voyager 1 & 2 spacecraft in 1980–1981.

There were four close targeted fly-bys by the Cassini orbiter: at a distance of 500 km on November 26, 2005,at a distance of 5,750 km on August 30, 2007, at a distance of 100 km on March 2, 2010 and at 69 km flyby on January 11, 2011.[25]. Rhea has been also imaged many times from long to moderate distances by the orbiter.

Gallery

-

Cassini color image of Rhea, showing the wispy trailing hemisphere

-

Higher-resolution image of the wispy hemisphere, showing ice cliffs

-

An artist impression of Rhea's rings

-

Composite image map of Rhea's surface

See also

Notes

- ^ In US dictionary transcription, Template:USdict.

- ^ The moons more massive than Rhea are: Earth's Moon, the four Galilean moons, Titan, Triton, Titania, and Oberon. Oberon, Uranus's second-largest moon, has a radius that is ~0.4% smaller than Rhea's, but a density that is ~26% greater. See JPLSSD.

- ^ More precisely, 0.3911 ± 0.0045 kg·m2.[8]

- ^ More precisely, 0.3721 ± 0.0036 kg·m2.[9]

References

- ^ Natural Satellites Ephemeris Service Minor Planet Center

- ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_24, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_24instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1086/508812, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1086/508812instead. - ^ Verbiscer, A.; French, R.; Showalter, M.; Helfenstein, P. (2007). "Enceladus: Cosmic Graffiti Artist Caught in the Act". Science. 315 (5813): 815. Bibcode:2007Sci...315..815V. doi:10.1126/science.1134681. PMID 17289992. p. 815 (supporting online material, table S1)

- ^ "Classic Satellites of the Solar System". Observatorio ARVAL. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ As reported by William Lassell, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 42–43 (January 14, 1848)

- ^ a b Anderson, J. D.; Rappaport, N. J.; Giampieri, G.; et al. (2003). "Gravity field and interior structure of Rhea". Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors. 136 (3–4): 201–213. Bibcode:2003PEPI..136..201A. doi:10.1016/S0031-9201(03)00035-9.

- ^ a b Anderson, J. D. (2007). "Saturn's satellite Rhea is a homogeneous mix of rock and ice". Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (2): L02202. doi:10.1029/2006GL028100.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.027, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.027instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1029/2007GL032898, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1029/2007GL032898instead. - ^ Anderson, John D. Rhea's Gravitational Field and Internal Structure. 37th COSPAR Scientific Assembly. Held 13–20 July 2008, in Montréal, Canada. p. 89.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|accessadte=ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.012, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.012instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.05.009, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2004.05.009instead. - ^ a b c d e Wagner, R.J.; Neukum; et al. (2008). "Geology of Saturn's Satellite Rhea on the Basis of the High-Resolution Images from the Targeted Flyby 049 on Aug. 30, 2007". Lunar and Planetary Science. XXXIX: 1930. Bibcode:2008LPI....39.1930W.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|author2=and|last2=specified (help) - ^ Schenk, Paul M.; McKinnon (2009). "Global Color Variations on Saturn's Icy Satellites, and New Evidence for Rhea's Ring". American Astronomical Society. 41. American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting #41, #3.03. Bibcode:2009DPS....41.0303S.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Cassini Finds Ethereal Atmosphere at Rhea". NASA. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.1198366, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.1198366instead. - ^ Saturn's Moon Rhea Also May Have Rings, NASA, June 3, 2006

- ^ Jones, G. H.; et al. (2008-03-07). "The Dust Halo of Saturn's Largest Icy Moon, Rhea". Science. 319 (5868). AAAS: 1380–1384. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1380J. doi:10.1126/science.1151524. PMID 18323452.

- ^ Lakdawalla, E. (2008-03-06). "A Ringed Moon of Saturn? Cassini Discovers Possible Rings at Rhea". The Planetary Society web site. Planetary Society. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Lakdawalla, E. (5 October 2009). "Another possible piece of evidence for a Rhea ring". The Planetary Society Blog. Planetary Society. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Matthew S. Tiscareno, Joseph A. Burns, Jeffrey N. Cuzzi, Matthew M. Hedman (2010). "Cassini imaging search rules out rings around Rhea". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (14): L14205. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3714205T. doi:10.1029/2010GL043663.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kerr, Richard A. (2010-06-25). "The Moon Rings That Never Were". ScienceNow. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ^ http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/news/cassinifeatures/feature20110113/

External links

- Rhea Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- The Planetary Society: Rhea

- Cassini images of Rhea

- Images of Rhea at JPL's Planetary Photojournal

- Movie of Rhea's rotation from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration site

- Rhea basemaps (released December 2010) from Cassini images

- Rhea altlas (released December 2010) from Cassini images

- Rhea nomenclature and Rhea map with feature names from the USGS planetary nomenclature page

- Saturn's moon Rhea has thin atmosphere