Selly Oak

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Selly Oak | |

|---|---|

View of Selly Oak High Street (A38 Bristol Road) looking south towards Northfield | |

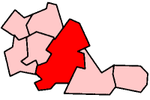

Location within the West Midlands | |

| OS grid reference | SP041823 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Shire county | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BIRMINGHAM |

| Postcode district | B29 |

| Dialling code | 0121 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Selly Oak is an industrial and residential area in south-west Birmingham, England. The area gives its name to Selly Oak ward and includes the neighbourhoods of: Bournbrook, Selly Park, and Ten Acres. The adjoining wards of Edgbaston and Harborne are to the north of the Bourn Brook, which was the former county boundary, and to the south are Weoley, and Bournville. A district committee serves the four wards of Selly Oak, Billesley, Bournville and Brandwood. The same wards form the Birmingham Selly Oak constituency, represented since 2024 by Alistair Carns (Labour). Selly Oak is connected to Birmingham by the Pershore Road (A441) and the Bristol Road (A38). The Worcester and Birmingham Canal and the Birmingham Cross-City Railway Line run across the Local District Centre.

The 2001 population census recorded 25,792 people living in Selly Oak, with a population density of 4,236 people per km2 compared with 3,649 people per km2 for Birmingham. It had 15.9% of the population consisting of ethnic minorities compared with 29.6% for Birmingham in general. As the University of Birmingham is nearby, there are many students in the area.

Toponymy

[edit]Selly Oak is recorded in the Domesday Book as Escelie.[1] The name Selly is derived from variants of "scelf-lei" or shelf-meadow,[2] that is, pasture land on a shelf or terrace of land, probably the glacial deposits formed after the creation and later dispersal of Lake Harrison during the Quaternary period. Another source for the name comes from the Old English 'sele' meaning a building, or a hall.[3]

History

[edit]Prehistoric

[edit]A small pit recorded in a service trench near Bournville Lane, Selly Oak produced the oldest pottery found in Birmingham so far. Twenty eight sherds, representing about five different vessels, in decorated Grooved Ware pottery of Late Neolithic date, were recovered. The Bronze Age pit found immediately adjacent to the site was also a highly important archaeological discovery, since prehistoric structures other than burnt mounds[4] are extremely rare in Birmingham.[5] Examples of finds in this area include:

Bond Street Stone Axe (MBM859); Bourn Brook Burnt Mound (MBM2484); Bourn Brook Burnt Mounds (MBM359); California, Burnt Mound (MBM777); Falconhurst Road Barbed and Tanged Arrowhead (MBM1776); King’s Heath/Stirchley Brook Perforated Implement, axe hammer (MBM1793); Moor End Farm Burnt Mound (MBM778). Northfield Relief Road pit (MBM2455). Ridgacre Burnt Mound, near Moor Farm (MBM779); Selly Oak Flint Flake (MBM2219); Selly Park Recreation Ground Prehistoric Finds (MBM2002); Shenley Lane, Northfield flint scraper (MBM1801); Ten Acres Burnt Mound (MBM1584); Vicarage Farm Axe Hammer (MBM860). Weoley Park Road Neolithic Flint Scraper (MBM869).[6]

Roman

[edit]Metchley Fort was established c. AD 48 and occupied until c. 200 AD.[7] Two Roman Roads appear to have met there. Ryknield or Icknield Street was laid out between Bourton-on-the-Water and Derby in the mid-to-late 1st century to serve the needs of military communication. It passed through Alcester, Selly Oak, Birmingham, and Sutton Coldfield to Wall. A little north of Birmingham it passed through the important military camp of Perry. At Bournbrook it threw off a branch called the Hadyn Way that passed through Stirchley and Lifford to Alcester. The road kept to the west of Birmingham to avoid the swamps and marshes along the course of the River Rea.[8] The second road is generally called the Upper Saltway running north from Droitwich Spa to the Lincolnshire coast. Its route is uncertain but is generally believed to follow the line of the A38.[9]

Droitwich and Alcester were connected by the Lower Saltway. Wall was previously a Roman centre named Letocetum and it was near here that Ryknield (Icknield) Street crossed Watling Street, now the A5, which ran north-west from London to Wroxeter.[10] The Staffordshire Hoard was found near here within a triangle of roads from the Roman and Anglo-Saxon periods that cannot all be dated.[11] Possible evidence of Roman remains exist in the place names of Stirchley (formerly Stretley and Strutley) Street; Moor Street, near Woodgate Valley in Bartley Green; and Street Farm in Northfield where two Turnpike Roads met.[12] Evidence of Roman activity through finds in the area include:

Allens Croft Road/Brandwood Park Road Roman Coin (MBM981); Harborne Bridge, Roman Road (MBM1639); Hazelwell Street Roman Road (MBM1902); Icknield Street, Walkers Heath, Roman Road (B12227); Lodge Hill, coin of Gordian III: Roman (MBM1020); Longdales Road Roman Farmstead (B12342); Metchley Roman Forts (MBM370); Northfield Relief Road pottery (MBM2421); Parsons Hill Roman occupation 0AD to 299AD (B1824); Raddlebarn Road Roman Coin (MBM988); Selly Oak Roman Coin – commemorative coin of Constantine 1 (MBM872); Selly Park Spindle Whorl (MBM982); Stirchley Roman Coin, a gold aureus of Vespasian minted at Tarraco in the last quarter of the year 70AD (MBM983); Stocks Wood irregular Earthwork (MBM1944); Tiverton Road Roman Coins – denarii (MBM2067); Weoley Castle Roman Coin of Antoninianus (MBM1016); Woodgate Valley Roman coin of Trajan (MBM1013).[6]

Anglo-Saxon and Norman

[edit]There are two entries in Domesday Book for Selly Oak (Escelie). The first entry for Selly Oak records a nuncupative (oral) will and is out of conventional order.[13] Wulfwin had leased the manor for the term of three lives and the newly appointed Bishop of Lichfield, Robert de Limesey, used the will to challenge the loss of his land. "Wulfwin bought this manor before 1066 from the Bishop of Chester, for the lives of three men. When he was ailing and had come to the end of his life, he summoned his son, the Bishop of Li (chfield?), his wife and many of his friends and said: 'Hear me, my friends, I desire that my wife hold this land which I bought from the church so long as she lives, and that after her death the church from which I received it should accept it back. Let whoever shall take it away from it be excommunicated'. The more important men of the whole County testify that this was so." The first entry records Bartley Green as an outlier, or dependency of Selly Oak, while the second entry doesn't include Bartley Green but records Selly Oak is held as two manors. The second entry also shows that Wibert had been replaced as sub-tenant by Robert suggesting the challenge may have been partially successful.[14] The Bishop of Chester owned Lichfield and its members. These include Harborne, in Staffordshire until 1891, which was held by Robert.[15]

Wulfwin owned several manors which indicates he was wealthy and important, possibly an aristocrat. Indeed, he has been described as a great thegn, the son of Wigod, and the grandson of Woolgeat, the Danish Earl of Warwick. His mother was the sister of Leofric III, Earl of Mercia. The possessions that came to him by the Dano-Saxon marriage of his parents seem to have been rather extensive. In King Edward the Confessor’s time Wulfwin (also referred to as Alwyne and Ulwin) was sheriff and through his son Turchill, who came to be Earl of Warwick, the Ardens and the Bracebridges trace their descent from the Old Saxon kings.[16]

One of the purposes of Domesday Book was to provide a written statement of the legal owners (Sub-tenants) and overlords (Barons) of the land in the reallocation of territories after the conquest. William Fitz-Ansculf, from Picquigny, Picardy in France, was assigned a Barony. He made his base at the Saxon, Earl Edwin’s, Dudley Castle. He and his successors were overlords of the manors of Selly Oak and Birmingham both of which had previously been owned by Wulfwin. It would appear that William Fitz Ansculf died during the First Crusade. Henry of Huntingdon in his 'History of the English People' writes that: "Then from the middle of February they besieged the castle of 'Arqah, for almost three months. Easter was celebrated there (10 April). But Anselm of Ribemont, a very brave knight, died there, struck by a stone, and William of Picardy, and many others."[17] Successors to the Barony included the Paganel and Somery families. In 1322 when John de Somery died the barony was divided between his two sisters Margaret de Sutton and Joan de Botetourt. Joan Botetourt was awarded a twenty-third of a knights fee in Selley which was held by Geoffrey de Selley who also held Bernak in Northamptonshire, and a quarter of a fee in Northfield which was held by John de Middleton.[18]

At the time of the Domesday survey in 1086 Birmingham was a manor in Warwickshire with less than 3,000 acres.[19] The current Birmingham Historic Landscape Characterisation project covers a total area of 26,798 ha (66,219 acres).[20] Birmingham developed in the hinterland of three counties – Warwickshire, Staffordshire, and Worcestershire. Nearly 50% of this territory was formerly in either Staffordshire[21] or Worcestershire but as the city expanded the ancient boundaries were changed in order that the area being administered came under one county authority – Warwickshire. The Saxon presence in the territory of modern Birmingham requires the inclusion of the Manors and Berewicks/Outliers mentioned in Domesday Book that are now part of the Birmingham conurbation. This is complicated by the fact that separate figures were not given for Harborne, Yardley, and King’s Norton which were all attached to manors outside the area.[22] The Birmingham Plateau had about 26 Domesday Book manors, a population of close to 2,000, with seven mills, and three priests.

Medieval

[edit]The earliest Tax Roll for Selly Oak was the Lechmere Roll of 1276–1282. Selleye (Selly Oak) and Weleye (Weoley) were separate from the manor of Northfield. Of the twenty households listed the person who paid the most tax was William de Valence, 1st Earl of Pembroke, who was the half-brother of Henry III and one of the wealthiest men in the kingdom.[23]

The Papal Register 1291 shows that Northfield was an Ecclesiastic Parish which was connected with Dudley Priory.[24] In the next Tax Roll in 1327 the entries for Selly Oak and Weoley were combined with those of Northfield. This suggests a time-frame for the establishment of the Parish of Northfield.[25]

20th century and contemporary

[edit]

Two tornadoes touched down in Birmingham on 23 November 1981 as part of the record-breaking nationwide tornado outbreak on that day. The second tornado, rated as an F1/T2 tornado, touched down in Selly Oak at about 14:00 local time, causing some damage across the southern suburbs of Birmingham.[26]

In the late 20th century a road-widening scheme for the Bristol Road (A38) was carried out. Many historic buildings, including the offices of Birmingham Battery and Metal Company and the Westley Richards Gun Factory, were demolished. However, plans for a major regeneration of the area were confirmed in 2005 and a new 1.5 km stretch of road was opened in August 2011 to access the new Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham. The work has involved the construction of the Aerial aqueduct to carry the Worcester and Birmingham Canal, and a railway viaduct for the Cross-City Line. This scheme has paved the way for the enhancement of the Battery Retail Park shopping complex and a number of familiar High Street shops have opened stores.

Manors and parishes

[edit]The ecclesiastical parish of Selly Oak (1861)[8] appears to identify the original boundary of the ancient manor.[27] The Order in Council at the Court at Windsor held on 7 June 1862 set the boundary as follows: "All that part of the parish of Northfield, in the County of Worcester, wherein the present incumbent of such parish now possesses the exclusive cure of souls, which is situate to the north-east of an imaginary line commencing upon the boundary dividing the said parish of Northfield from the parish of Harborne, in the county of Stafford, and in the diocese of Lichfield, at a point in the middle of the road leading from Hart’s Green, past Shenley Field Farm, to the Birmingham and Bromsgrove Turnpike road; and extending thence, in a direction generally south-ward, along the middle of the said road leading from Hart’s Green aforesaid to a point in the middle of the said Turnpike road near to White-hill; and extending thence north-eastward, along the middle of the same Turnpike road for a distance of five hundred and twenty-eight yards, or thereabouts, to a point opposite to the middle of the northern end of Hole Lane; and extending thence, south-eastward, to and along the middle of such lane as far as a point opposite to the middle of the last named lane; and then generally north-eastward, along the middle of the same lane, to the boundary dividing the said parish of Northfield, from the parish of King’s Norton, in the county and diocese of Worcester aforesaid at a point in the middle of Gallows Brook".[28]

In Domesday Book Berchelai now Bartley Green was identified as an Outlier of Selly Oak.[29] The boundaries of the daughter parish of Bartley Green were established in 1838.[30] There are errors concerning Bartley Green that need to be corrected. The VCH Warwickshire – City of Birmingham states: "The ancient parish of Northfield, covering 6,011 acres, was also originally in Worcestershire, its northern boundary with Harborne (formerly in Staffordshire) and Edgbaston (formerly in Warwickshire) being marked by the Bourn Brook, part of its eastern boundary with King’s Norton by the Rea and Griffins Brook. Except for under 200 acres of the north-west tip of the parish, which was added to Lapal civil parish, Northfield was included in Birmingham in 1911; from 1898 until then it had been part of the Urban District of King’s Norton and Northfield".[31] The portion not included in the transfer to Birmingham was transferred to Illey not Lapal.[32] The online version of the transfer states: "The parish of Northfield is situated on the northern border of the county, but with the exception of the Bartley Green area, which was annexed to Lapal, Northfield was incorporated in the city of Birmingham by the Birmingham Extension Act, 1911".[33] This has repeatedly been misread to exclude the whole of Bartley Green from incorporation into Birmingham.

The three Domesday Book manors of Northfield, Selly Oak and its outlier Bartley Green formed the Parish of Northfield in Worcestershire.[34] The Domesday Book manor of Northfield was not coterminous with the later parish of Northfield. Unfortunately there has been some confusion between manor and parish. As this has had an adverse impact on Selly Oak, and also Bartley Green, it seems advisable to identify the boundaries of Northfield.

In Domesday Book Northfield had a priest and was valued at £8 before 1066.[35] This suggests it was an ecclesiastical centre at the time of the Norman Conquest. As no sub-tenant was appointed was Northfield, which shares a boundary with King’s Norton (Nortune), a royal manor?

The 1820 sale of the manor of Northfield and Weoley defines the boundary of the ancient manor. "One of the Lots will comprise the extensive Manor of Northfield and Weoley, with several eligible Farms, containing together about 1200 acres, principally tithe free, lying within a ring fence, and let to respectable tenants, at moderate rents. This Lot is very eligible for the investment of capital, or might suit any Gentleman desirous of residing on his own estate, there being on one of the Farms a very commodious House, with suitable outbuildings, which, at a moderate expense, might be rendered a desirable residence, being within a convenient distance from the Birmingham and Worcester Turnpike Road, and not, intersected by any public carriage road, and affording every facility for the preservation of game. Many of the other Lots adjoin the Turnpike Road, and are very eligible as building ground, and the whole Estate is well circumstanced with regard to roads and navigable canals. The whole of this property, with the exception of the Glebe in Cofton Hackett, is situate in the parish of Northfield, in the County of Worcestershire, on the high turnpike road from Birmingham to Worcester, and is distant five miles from the former place".[36]

A map of the estate was drawn up by J & F Surveyors in 1817 and this provides more useful information. Two turnpike roads met at Northfield. The Birmingham and Worcester turnpike road which is now the Bristol Road (A38) and the Northfield to Wootton Wawen turnpike road which runs southwards down Church Hill, past Turves Green and West Heath until it joins the Alvechurch Road (A441). As this was also a direct route to Evesham it may have been a medieval, if not older, route. The map shows two mills, Northfield (Digbeth) and Wychall which would fit with the description of Weley Manor on the death of Roger de Someri in 1272.[37]

Two manor house sites were shown amongst the lots. Middleton Hall was presumably the location of the residence of the Middleton family.[38] The larger moated site, adjacent to the Church, is suggested to have been the original manor house of Northfield.[39] The claim that stone from the Quarry Lane site was used to build Weoley Castle is interesting and questionable.[40] Weoley Castle lies just north of a rocky outcrop between Jervoise Road and Alwold Road from which the stone was cut.[41] a further point for consideration is that Great Ley Hill was included among the lots for sale. Five of the fields were called: 370 Round Wheely, 371 Round Wheeley, 372 Long Wheeley, 1114 Middle Wheely, and 1115 Long Wheely.[42] Fernando Smith, who owned 123 acres, was an heir of the Barony of Dudley had it not gone into abeyance.[43]

The parishes of Northfield and King’s Norton joined to form a Rural District Council which quickly changed to King’s Norton and Northfield Urban District Council in 1898.[44] The opportunity to form an independent Borough was resisted in favour of unity with Birmingham City Council. In 1911 the area administered by Birmingham was almost trebled by a further extension of its boundaries under the Greater Birmingham Act.[45] Previous extensions in 1889, 1891, and 1911 had seen Birmingham grow from 2,996 acres to 13,478 acres. Balsall Heath (1891) and Quinton (1909) were both transferred from Worcestershire, while Harborne was transferred from Staffordshire. In 1911 the boundaries were extended to include: the borough of Aston Manor (Warwickshire); Erdington Urban District (Warwickshire); Handsworth Urban District (Staffordshire); most of King’s Norton and Northfield Urban District (Worcestershire); and Yardley Rural District (Worcestershire).[46] The area administered by Birmingham was almost trebled from 13,478 acres to 43,601 acres.[47]

Further additions to the city were made in 1928 and 1931, and after the VCH Warwickshire Volume V11 – The City of Birmingham was first published in 1964 making an updated study desirable, particularly regarding the transfer of areas from the neighbouring counties of Worcestershire and Staffordshire. An editorial note states that "Accounts of the Worcestershire Parishes, that ceased to exist when the administrative authority of Greater Birmingham was established, are contained in Volume III of the VCH History of Worcestershire".[48] The Historic Landscape Characterisation of Birmingham covers a total area of 26,798 ha (66,210 acres) giving an indication of the growth of Birmingham since 1889.[20]

Industrialisation

[edit]Lime kilns

[edit]The archaeology report following an excavation identifies that the limekilns were built shortly after the Dudley Canal line No. 2 was opened in 1798.[49] A map of 1828 showed five lime kilns within a single block on James Whitehouse’s Wharfs on the Worcester to Birmingham canal. There was some rebuilding during the 1850s and they were redundant by the 1870s. The two eastern kilns were truncated by the railway. Older kilns may be buried beneath those that were excavated. The block of kilns would have dominated the landscape at the time and were designed to satisfy an obviously large demand. They were on a direct route to Birmingham’s first gasworks opened in 1818 at the terminus of the Worcester and Birmingham Canal.

They represent one of the earliest industries established in Selly Oak area which are associated with the Industrial Revolution. This is early evidence of a large scale industrial process taking place in Selly Oak and of great significance for Birmingham. They are the only ones of their type excavated in Birmingham.

Other items found during the excavation revealed post-medieval pottery: Cream-wares dateable to 1760-1780 predate the lime kilns although it wasn't always possible to excavate below the existing structures. Red sandy-ware also suggests a late 18th-century date.[49]

In 1822 the canal company approved the takeover by William Povey of the coal and lime business already established on the wharf by a Mr. James. The tenancy was transferred to James Whitehouse of Frankley in 1836. He lived on the wharf, carrying on a business in coal and lime and also keeping a shop until the 1870s.[50] On the Dudley Canal side of the Birmingham Battery and Metal Co Ltd there are indications of further lime kilns beside William Summerfield’s wharfs that have not been excavated.

Chemical industry

[edit]When John Sturge died Edward brought his brother-in-law, Arthur Albright, into partnership. They first made white phosphorus in 1844 but this was volatile. Albright invented a process of manufacturing red, or amorphous, phosphorus for which he obtained a patent in 1851. Their chemical works was reported to have caused several explosions. When an application is made for building work, as part of the regeneration programme for Selly Oak, it will have a condition for an archaeological excavation of the site to be carried out. A newspaper article in 1839 concerning the damage caused by a hurricane reported that 20 yards of a substantially built wall was demolished at Sturges Works and at the Sal-ammonite works of Mr Bradley at the same place, 30 feet of the large stack was hurled to the ground with such tremendous force as to destroy a stable and dash in a portion of the roof of the evaporating house connected with the building.[51]

Selly Oak well and pumping station

[edit]Near to the library and set back from the Bristol Road is a tall, enigmatic listed building. Selly Oak Well and pumping Station was built by the Birmingham Corporation Water Department in the 1870s but was not formally opened until July 1879 by Joseph Chamberlain. The well was 12 feet in diameter and with a total depth of 300 feet. It has a solid casing of masonry 14 inches thick extending 80 feet from the surface. The engine beam was 31½ feet in length and weighed 20 tons. The cylinder was 60 inches in diameter and had a stroke of 11 feet. It was built by Messrs James Watt and Co. By 1881, after further lateral borings, the output was one and a quarter million gallons each day. The well was capped in 1920 as the Elan Valley supplied all the water that was required. The building is described in its national listing as a tall brick and terracotta building with stone dressings, in a Gothic style associated with Chamberlain. It appears as a tall version of a French Gothic Chapel.[52]

Transport and communications

[edit]Roads

[edit]The former Bristol Road trams were replaced with buses in 1952.[53] The original tram sheds were demolished around 2005 to make way for flats, and Selly Oak bus garage closed as an operational garage in 1986 but continued as a vehicle store for West Midlands Travel. It was converted into a self-storage depot around 1990.[53]

The majority of bus services are operated by National Express West Midlands including the 11A/11C Outer Circle. First Midland Red operated service 144 between Birmingham and Worcester via Bromsgrove. First curtailed service 144 at Catshill from 1 May 2022 due to low passenger numbers.

Canals

[edit]2015 was the bi-centenary of the opening of the Worcester and Birmingham canal (1815–2015). This connected Birmingham to Worcester and the River Severn, and then to Gloucester with its International trade routes. The speed with which the canal system was constructed is phenomenal, perhaps due to the war with France that began in 1793, and the need to transport the heavy minerals – coal, iron-ore, and limestone from the Black Country. Selly Port was the centre of activity. The Worcester and Birmingham Canal Act 1791 (31 Geo. 3. c. 59) approved the construction and with two further acts authorised the raising of £379,609 to pay for it. Barracks to accommodate the navvies at were established Bournbrook for 120 men, and Gallows Brook, Stirchley for 100 men. Between Selly Oak and Ley End to the south of the Wast Hill Tunnel six brick kilns were in operation. The network included three canals: the Worcester-Birmingham, the Netherton, or Dudley Canal line No. 2, and the Stratford-upon-Avon Canal.

The construction work involved: cuttings, bridges, tunnels, aqueducts, and embankments that were all built using manual labour from 'navvies'. Some of the bridges were initially constructed from wood with accommodation drawbridges, or roving bridges, inserted where the canal cut across farms or estates. Initially few locks were needed other than stop-locks or the guillotine Lock at King’s Norton. There were three tunnels: Lapal (3,795 yds), Brandwood (352 yds), and Wast Hills Tunnel (2,726 yds).

The section of the Worcester-Birmingham canal to Selly Oak was opened in 1795. In May 1798 the Netherton to Selly Oak canal was opened to great festivities. By 1802 a route was opened from Dudley to London. To appease mill owners, reservoirs were constructed at Harborne, Lifford Reservoir and Wychall Reservoir. In 1815 issues regarding the Worcester Bar in Gas Street, Birmingham were resolved and the final section through Tardibigge to Worcester was completed.[54]

Arrangements have been negotiated for reinstating part of the Dudley No. 2 Canal through the former Birmingham Battery and Metal Company site, as part of a long-term plan to re-establish the canal route to Halesowen and the Black Country.[55]

Rail

[edit]The Birmingham West Suburban Railway agreed a land rental deal with the Worcester and Birmingham Canal to allow construction which was authorised in 1871, and opened as a single line track in 1876 from Granville Street to Lifford. The Birmingham West Suburban Railway was bought out by the Midland Railway to allow their trains to pass through Birmingham without turning having used the Camp Hill line, they extended the tracks south to a junction south with the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway at Kings Norton, and double-tracked the entire line length. The line was slightly realigned in the early 1930s. The stub of the old alignment has recently been demolished. Five stations were opened including Selly Oak. The terminus was changed to New Street. The line was doubled in 1883, and by 1885, it had become the Midland Railway’s main line to Gloucester. During World War I casualties were transported into Selly Oak and transferred to the First Southern and General Military Hospital which was housed in the new University of Birmingham buildings. The convoys often ran at night to avoid noise and traffic, and to limit the demoralising sight of the considerable number of people wounded during the conflict. In the 1920s the central part of the viaduct over the Bristol Road was replaced with the current steel bridge to enable higher trams to pass beneath it. The station complex was rebuilt in 1978 and again in 2003.[56]

Selly Oak is currently served by Selly Oak railway station on the Cross-City Line, providing services to the Birmingham New Street, Lichfield Trent Valley, Redditch and Bromsgrove stations.

The 'Oak' tree

[edit]The Oak element of the name Selly Oak comes from a prominent oak tree that formerly stood at the crossroads of the Bristol Road and Oak Tree Lane/Harborne Lane. The original spot is still commemorated by an old Victorian street sign above one of the shops on the north-side of Oak Tree Lane, which declares it to be "Oak Tree Place" and has the date of 1880.[57]

The oak that stood there was finally felled in May 1909 amid fears about its safety, due to damage to its roots caused by the building of the nearby houses. The tree was cut-up and the stump removed to Selly Oak Park, where it remains to this day, bearing a brass plaque that reads "Butt of Old Oak Tree from which the name of Selly Oak was derived. Removed from Oak Tree Lane, Selly Oak 1909".[58] By 2011 the stump had become quite rotten and the brass plaque was no longer secure. It was removed by the Friends of Selly Oak Park and replaced with a replica plaque. The original was retained by the Friends for conservation. The remains of the stump were left in the park.

The earliest attestations for the name 'Selly Oak' date from 1746, and come from the manorial court rolls for the Manor of Northfield and Weoley, of which the district of Selly was a part.[59] The stump of the old oak in Selly Oak Park was examined using dendrochronology, and the results gave a date of 1710–1720 for when the tree began growing.[60] It is therefore thought that the tree became a landmark following the turnpiking of the road from Bromsgrove to Birmingham (now the Bristol Road), which began in 1727.[61]

An older name for the same crossroads, where the road from King's Norton to Harborne (now represented by Oak Tree/Harborne Lanes) met the Bromsgrove to Birmingham road (now the Bristol Road), appears to have been Selly Cross; at least this is what it was called during the 16th century when it was recorded as Selley Crosse in 1549 and Selley Cross in 1506.[62]

The supposed tradition that the original oak was associated with a witch named Sarah or Sally is without foundation,[63] and is likely to have arisen as a means of explaining what may have been a variant and local pronunciation of the name as 'Sally' Oak.[64] Indeed, the name is actually recorded as Sally Oak on a canal map produced by John Snape in 1789.[65]

In March 1985, a 'new' Selly Oak was planted by local Councillors on the north side of Bristol Road on the small triangle of land between Harborne Lane and the Sainsbury's site, following road improvements to the junction.[66] A second 'new' Selly Oak was planted in October 2000 at Bentella's Corner on the south side of Bristol Road, on the opposite side of Oak Tree Lane to the original site.[67] In addition, there may also have been a third planting of yet another 'new' Selly Oak, next to the extension to Sainsbury's car park, after the demolition of The Great Oak pub in 1993.[citation needed] All of these Oaks are still[when?] growing.

Education

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2023) |

Schools include Selly Oak School, Selly Park Girls Technology College, St Edwards RC, Raddlebarn Primary & Nursery, Tiverton Road, and St Mary's C of E Primary School.

The following is the history of the schools in Selly Oak Ward taken from the Victoria County History that was published in 1964 and accordingly the information requires updating.[68]

St Edwards RC Primary School, Elmdon Road: The school opened 1874 as St Paul’s RC School, in new buildings with one schoolroom and one classroom. It moved into new buildings in 1895 and the name changed to St Edwards RC School. A new schoolroom was provided in 1897 increasing the accommodation for 120 children. It was altered and enlarged in 1909 and further improvements were required in 1912. In 1953 it was reorganised for Junior and Infants. Teaching was conducted by the Sisters of the Charity of St Paul.

St Mary’s C of E Primary School, High Street, Selly Oak (Bristol Road): It opened as a National School in 1860 with accommodation for 252 children. It was enlarged in 1872 and ten years later the boys and girls were separated. When St Mary’s National School was opened in Hubert Road Bournbrook in 1885 the girls were transferred there and the National School was used for boys and infants. In 1898 the schools were united for administration and called Selly Oak and Bournbrook Schools. A third department was opened in 1898, in Dawlish Road, to accommodate 545 senior girls and the Infants department. Selly Oak School was used for junior girls and Infants. Bournbrook School was used for boys with accommodation for 200 boys provided at the Bournbrook Technical Institute from 1901 to 1903. The original school was on the Bristol Road between Frederick Road and Harborne Lane. It was rebuilt on Lodge Hill Road and the old building was demolished in order to widen the road.[69]

The Selly Oak and Bournbrook Temporary Council School was opened by King’s Norton and Northfield UDC in 1903 in the room that was previously used as an annexe of Selly Oak and Bournbrook C of E School. The premises were not satisfactory and the school was closed in 1904 when Raddlebarn Lane Temporary Council School was opened. Selly Oak School was damaged in 1908 by a gale and the premises were condemned in 1912. The schools were separated in 1914 with the 1885 Hubert Road and 1898 Dawlish Road buildings becoming St Wulstan’s C of E school. Selly Oak School became St Mary’s C of E School. In 1946 accommodation was also provided in the People’s Hall, Oak Tree Lane.

Selly Hill C of E, Warwards Lane. Ten Acres Church School opened in 1874 to accommodate 125 children. The name changed in 1884 to Selly Hill Church School. It was sometimes known as St Stephen’s Church School, or as Dogpool National School. It was enlarged in 1885 and a new school was opened on an adjoining site opened in 1898 to accommodate 440 children. Further enlargement and alterations took place in 1914, and after reorganisation in 1927 and 1931 the school closed in 1941. Between 1951 and 1954 the buildings were used by Selly Park County Primary School and from 1954 by Raddlebarn Lane Boys County Modern School.

Selly Oak Boys County Modern School, Oak Tree Lane, was opened in 1961 with nine classrooms, practical rooms and a hall.

Selly Park County Primary School, Pershore Road, opened in 1911 to accommodate 1,110 boys, girls and infants and enabled the closure of Fashoda Road Temporary Council School. The buildings were altered and the school reorganised in 1931–32. In 1945 the senior department became a separate school. St Stephen's Parochial Hall provided accommodation for two classes from 1947 to 1954. War damage was repaired in 1950 and in 1955 children were transferred to Moor Green County Primary School with one building used as an annexe of this new school.

Selly Park Girls' County Modern School, Pershore Road became a separate school in 1945, accommodating 440, in the buildings of the County Primary School.

Fashoda Road Temporary Council School was opened by King’s Norton and Northfield UDC in 1904 and closed with the opening of Selly Park Council School.

Raddlebarn Lane County Primary School In 1905 King’s Norton and Northfield UDC opened a temporary school in iron buildings for the Selly Oak and Bournbrook Temporary Council School from the Bournbrook Technical Institute. Accommodation for 126 was provided in a Primitive Methodist Chapel. Permanent buildings replacing the hut opened in 1909 as Raddlebarn Lane Council School with accommodation for 800 children.

Raddlebarn Lane Boy’s County Modern School This became a separate school in 1945 with additional accommodation provided in 1951 in the Friends Meeting House, Raddlebarn Road, and from 1954 in the former St Stephen’s C of E School in Warwards Lane.

Selly Oak colleges

[edit]This information has been gathered from the Victoria County History which was published in 1964 so there is a need to add to it.[70]

Woodbrooke College, Bristol Road.[71] This was the former home of Josiah Mason, George Richards Elkington, and George and Elizabeth Cadbury. It was opened in 1903 as a residential settlement for religious and social study for Friends. A men’s hostel, Holland House was opened from 1907 to 1914. By 1922 more than 400 foreign students and 1,250 British students had passed through the college. Only about 50% of these belonged to the Society of Friends.

A separate missionary college was established at Westholme in 1905, this was the house of J W Hoyland. A year later it moved into permanent quarters at Kingsmead. By 1931 the Methodists had added Queen’s Hostel for women.

Westhill College was created in 1907 as a result of gifts by Mr. and Mrs. Barrow Cadbury. The building erected in 1914 was named after its first principle, G H Archibald.

Fircroft College was a working men’s college conceived as a place of training for Adult-School workers. The college moved to The Dell in 1909 which was renamed Fircroft. The college moved in 1957 to Primrose Hill, George Cadbury’s old home, and this was renamed Fircroft.

Carey Hall, Weoley Park Road was opened in 1912 as a joint venture of the Baptist Missionary Society, and the London Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church of England for training women missionary candidates.

The College of the Ascension, opened 1929, replaced the original Westhill College building as a training institution for women missionaries for the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.

The YWCA College began work in 1926 moving to new premises in College Walk.

The Churches of Christ Theological College moved from Park Road, Moseley to Overdale in 1931.

The Beeches, built by George Cadbury before 1914, was used from 1925 to 1933 as a holiday home for non-conformist ministers and their wives. It became The Beeches Educational Centre for Women from 1933 to 1939. After the War it was used by Cadbury Brothers Ltd as a trade college.

St Brigid’s House, Weoley Park Road, was a second Anglican college, which initially shared premises with the College of the Ascension.

The Anglican Industrial Christian Fellowship Training College was also situated in Weoley Park Road from 1954 to 1956.

St Andrews College, a united men’s missionary college was opened in Elmfield before moving to Lower Kingsmead.

A Central Council of governing bodies of the colleges was created in 1919. George Cadbury gave extensive playing fields in 1922 on which a pavilion was erected in 1928. The Rendel Harris Reference Library, named after the first tutor at Woodbrooke College, was opened in 1925 in a large house called Rokesley. After World War 2 the building was extended and became the Gillett Centre for students' recreation and sports.[72] It had a swimming pool and squash courts. The George Cadbury Memorial Hall was built by Dame Elizabeth Cadbury and opened in 1927. A new library was built in 1932.[73]

A new Life Sciences campus will be created for the University of Birmingham.

King's Norton union workhouse

[edit]Selly Oak Hospital began as a workhouse.[74][75] It was built in 1872 for the King’s Norton Poor law Union which was formed in 1836 and included the Parishes of Beoley, King’s Norton, Northfield (Worcestershire), Harborne and Smethwick (Staffordshire), and Edgbaston (Warwickshire). The architect was Edward Homes who had designed St Mary’s Church. By 1879 the hospital catered for 400 patients including the poor but also the aged, sick, and infirm. In 1895 the foundation stone was laid for a new infirmary designed by Daniel Arkell. In 1906 the Woodlands was built as a home for nurses. The school of nursing was officially opened in 1942.[76]

In 1911 Selly Oak became part of the Birmingham Union for Poor Law responsibility. By the Local Government Act 1929 the functions of the boards of guardians were transferred to the local authorities and Birmingham Corporation became responsible for the administration of public assistance and for 16 institutions containing 6,000 patients. Selly Oak hospital, with 550 patients, was administered by the public health, maternity, and welfare committee becoming a general and not poor law hospital.[77] For many years the workhouse and infirmary buildings have been used as offices and consulting rooms rather than as wards for patients. The main prosthetic limb production and fitment centre for the West Midlands is still functioning.

The Centre for Defence Medicine was located at Selly Oak Hospital and casualties from the Iraq War and War in Afghanistan were treated there. When the university hospitals Birmingham trust NHS foundation trust was formed in 1997 Selly Oak Hospital and the Queen Elizabeth Hospital were jointly administered. A new hospital has been built beside the old QE and Selly Oak Accident and Emergency Department was closed with the transfer of patients beginning on 16 June 2010. The hospital in now fully closed, with all NHS services consolidated to the new Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham. A significant group of buildings have been listed but 650 houses will be built on the site.[78]

Community

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2023) |

The area is well served by all kinds of public facilities. These include: - Selly Oak Library which hosts the Selly Oak Library Local History Group.

Cinemas

The Oak Cinema was at the junction of the Bristol Road and Chapel Lane where Sainsbury’s supermarket is now. The cinema opened in 1924 and was later extended to seat over 1,500.[79] The ABC minors children's cinema club took place on Saturday mornings. The cinema closed in November 1979.[80]

The ‘Stickleback Picturedrome' was built in chapel Lane in 1913 beside the Plough and Harrow. In 1924 it was converted to a billiard hall and in 1950 became the Embassy Dance Club.[81]

The People’s Hall, in Oak Tree Lane was used as a 'picturedrome' for a few years around 1911.[82]

Cemetery

There is one main cemetery in Selly Oak, Lodge Hill Cemetery, opened 1895, and run by Birmingham council since 1911. In 1937 Birmingham’s first Municipal Crematorium was built on the site.[83] Its main entrance is on Weoley Park Road, at its junction with Gibbins Road and Shenley Fields Road.

Historic public houses

Photographic evidence exists for all of these pubs with the exception of 'The Boat' and 'The Junction'.

The Bear and Staff is situated at the junction of Bristol Road and Frederick Road.

The Boat was an early pub, beside the canal at the bottom of the Dingle, kept by Mr. Kinchin.[84]

In 1881 the Country Girl, Raddlebarn Road, is listed as a beer garden. It has undergone various modifications. The cottages on the site have been used to give a more acceptable address to those born in the Workhouse.[85]

Behind the façade of the Dog and Partridge was an old farmhouse which had sold its home-brewed beer from the early days of Selly Oak’s canal-side development. It had been run by an independent beer retailer, Butler’s of Wolverhampton, until 1938 when Mitchells and Butler bought it.[86] It was positioned on the front of 'The Dingle'. One of the people accused of and incorrectly imprisoned for the Carl Bridgewater murder was arrested in the now demolished Dog and Partridge public house. The pub and the Commercial buildings were demolished from the 1998s.

The original Dogpool Inn was on the corner of Pershore Road and Dogpool Lane, diagonally opposite where the current pub stands. It appears on an 1877 map. The landlord was Tom G H Thompson.[87] It has had various names: Firkin, Hibernian and is now the New Dogpool Hotel It is an Art Nouveau style building with terracotta facing and a French Empire type roof.[88]

The Junction Inn was situated on the canal wharf at the junction of the Dudley and W/B canals – a large house is shown on an 1873 map.[89]

The Great Oak was a new pub opened on the Triangle; however access was nearly impossible due to traffic.

The original Oak Inn was on the corner of the Bristol Road and Harborne Lane. It was demolished during road improvements and for the development of the Triangle for the now closed Sainsbury’s store c. 1980.[90] A Court of the Ancient Order of Foresters was held at the Oak Tree in Selly Oak.[91]

The Prince of Wales was on the site of Halfords on the Battery Retail Park.[92]

The Plough and Harrow was formerly called the New Inn and took the name Plough and Harrow in 1904. The pub had moved to this site from further up the Bristol Road towards the Oak in about 1900. It was demolished for junction improvements in the 1980s.[93]

The Selly Park Tavern, Pershore Road, was built in 1901 as the Selly Park Hotel, in the Arts and Crafts style for Holders Brewery. It replaced the Pershore Inn which probably dated back to the building of the Pershore Road in 1825. A skittle alley at the back is possibly one of the earlier Inn’s outbuildings.[94]

Ten Acres Tavern was on the corner of Pershore Road and St Stephen's Road which is now occupied by the New Dogpool Hotel. It was built by Holt’s brewery.[87]

In 1900 the Village Bells, Harborne Lane, had William Caesley as landlord. It had become the Infant Welfare Centre by 1922. The building was reputedly used as a meeting place for the Primitive Methodists. The site was cleared for road widening.[95]

The White Horse was in Chapel Lane.

Television

The BBC Drama Village is situated in Selly Oak, together with the Mill Health Centre where the BBC's daytime soap Doctors is filmed.

Places of Worship

[edit]

George Richards Elkington put up most of the money to build St Mary's Church on Bristol Road in 1861, built by the Birmingham architect Edward Holmes. There are several Elkington Burials in the Churchyard, including George Richards Elkington and his wife Mary Austen Elkington., and Brass Plates to Commemorate them within the name of the church. These rather amusingly show the couple with Victorian hairstyles and a mixture of Victorian and medieval clothing.

The Five Mile Act in 1665 meant Birmingham, although a large centre of population was not a borough, and was therefore exempt from the effects of the Act and attracted an influx of ex-preachers religious freedom made the town attractive. The Declaration of Indulgence of 1672 resulted in the licensing of meetings of which few seem to have been registered. The following is an update from the VCH City of Birmingham.[96]

A Psychic Centre on the Bristol Road, Selly Oak was registered for public worship in 1946.

Christ Church, Selly Park, was formed from St Stephen’s parish.

There are two large Pentecostal congregations in Selly Oak. Selly Oak Elim Church (now called Encounter Church is situated in Exeter Road. Meanwhile, Christian Life Centre is located on Langleys Road in a purpose-built church opened in 1999 (the congregation had previously worshipped at Dame Elizabeth Cadbury School in Bournville). CLC hosts three meetings on Sundays and has a regular attendance of three hundred or more worshippers at its two morning services. CLC is also heavily engaged in social outreach work through its ACTS and ARK projects to assist vulnerable and marginalised people in the local area.

Raddlebarn Lane Mission Hall was opened in 1922. It was preceded by a corrugated iron building, seating around 150, built on the same site by Edward Cadbury in 1903. It was originally known as the Friends' Hall, Selly Hill which was destroyed by fire in 1916. During the intervening period the congregation met at Raddlebarn Lane Council School. The hall was closed in 1950 and subsequently used by Birmingham Corporation for educational purposes.[97]

Selly Park Baptist Church was completed in 1877, at a cost of £3,400 of which W Middlemore subscribed £2,600 and, in 1892 provided 400 sittings. Services had previously been held in the Dog Pool Chapel, a wooden mission hall erected in 1867 in ST Stephen’s Road by members of Bradford Street Circus Chapel. The Sunday afternoon congregation in 1892 was 90. Church membership, 228 in 1938, had fallen in 1956 to 82. The congregation now meets in a new brick built annexe to the old church which is being renovated for use as a club.[98]

St Paul’s Convent was founded in 1864 by the Sisters of Charity of St Paul but the mission was not established until 1889. A stable and coach-house in Upland Road was used until a school was built and part used as a chapel in 1895. The permanent church was opened in 1902 and completed in 1904. A new chapel was built in c. 1915. The Sisters managed a maternity home in Raddlebarn Road which is now St Mary’s Hospice.

The Society of Friends Meeting on the Bristol Road was in a brick building, seating 200, opened in 1927. Christian Society Meetings for worship are said to have been held in the Workman’s Hall, Selly oak from 1879, and in 1892 there was a Sunday evening congregation of 170 at Selly Oak meeting in a building seating 200.

The Workman’s Hall was a temperance club on the 'British Workman' model, built on the initiative of a group on Unitarians in 1871.

Wesley Hall, a wooden building seating 150 on the Pershore Road, Selly Park, was opened by the Wesleyans in 1920 and cost £2,033. In 1940 three ancillary rooms were in use, of which one was built as a school hall. The congregation had previously met in an annexe of the council hall. Attendance in 1920 was estimated as 50, of whom 30 were church members. In 1932 membership was 38. The hall ceased to be registered for public worship in 1956.

Industry

[edit]William Bradley’s Sal-ammonite works were damaged by a hurricane when the chimney fell into the works in 1839. Bradley went bankrupt and his premises were bought by Sturges Chemical Works.[51]

The Birmingham Battery and Metal Co Ltd began in 1836 in Digbeth from where they moved to Selly Oak 1871. A large part of the factory area was turned into a retail business park in c. 1990 and the works closed in c. 1990 and the buildings were demolished. Only the offices building remained thought by most to be a statutory listed building. There was local shock when this significant landmark building was also demolished. The company was founded by Thomas Gibbins in 1836 and became a limited company in 1897. Joseph Gibbins (1756–1811) was a banker and button maker from South Wales. He was a partner of Matthew Boulton in establishing the Rose Copper Mine. His son, Thomas Gibbins (1796–1863), took over the management of the business. 1n 1884 the very tall chimney was erected and became a local landmark.[99] The Birmingham Battery and Metal Co Ltd used steam engines at Digbeth to work its battery hammers for making hollow-ware. A gas works was built on the site to power the engines driving the five large and several smaller rolling and tube mills, as well as provide lighting. This gas engine was sold in the 1920s, and the steam engines were gradually scrapped from 1908 onwards until by 1926 the factory was all electric. The company also had its own wells and during a drought supplied the canal company with water. The Gibbins family donated the land for Selly Oak Park and Selly Oak Library.[100]

Boat builders: 1820s John Smith, James Price; c. 1850-70 William Monk; 1870-1894 William Hetherington followed by Edward Tailby until 1923. Matthew Hughes and Sons until the 1930s.[101]

The 1884 First Edition OS map shows a brickworks on the site of the Birmingham Battery and Metal Company Ltd.

W Elliott & Sons, Metal Rollers and Wire Drawers were established in 1853 on the site of Sturges Chemical Works. Elliott’s Patent Sheathing and Metal Co. was formed in 1862.[102] In 1866 they bought Charles Green‘s business. Charles Green had taken out a patent (1838) for "seamless" tubes with respect to the drawing of copper tubes.[103] In a major expansion plan in 1928 they were taken over by ICI Metals Group and in 1964 transferred to Kynock Works at Witton.[104] Their products included rolled brass and copper sheet, drawn brass and copper wire, brass and copper tubes. There was significant production of an alloy known as Muntz metal, a patent of George Frederick Muntz, used for sheathing the hulls of wooden ships. They also made telegraph wire for the post office. The management included Neville Chamberlain from 1897 to 1924. During the war they made munitions and also millions of rivets for army boots.[105]

Goodman and Co Builders Merchants acquired Edward Tailby’s wharf to add to the land they had near the railway bridge from 1905. They transported bricks, slates, sand, cement, and other building materials from their wharf basin. They also supplied domestic fuel and coal. The canal arm was filled in around 1947 and used to extend the builder’s yard which continued to operate until 2000. In 1879 it supplied the materials to build the Birmingham Council House[106]

Guests Brass Stamping, formerly part of Guest, Keen, and Nettlefolds, was taken over by Birmingham Battery and Metal Company Ltd.

Architects drawings for a new frontage for the Premier Woven Wire Mattress Company Ltd onto Harborne Lane were dated 1947. It is known that the premises were destroyed by fire.

Selly Oak is thought to have mechanised the nailing trade using wrought iron.

Map evidence shows that Oak Tree Tannery was established functioning between 1840 and 1884 but as yet there is no indication of when it may have started and when it finished operating.

Sturges Chemical Works founded by John and Edmund Sturge, brothers of the more famous Joseph Sturge, occupied a site in Selly Oak from 1833 to 1853. On the 1839 Tithe Map and apportionments it is described as a vitriol works and yard. The land was owned by Henry Baron and James Rodway.[34]

The brothers founded a company, making dyer’s solutions, at Bewdley in c. 1822. They increased their range of products to citric acid, used in the making of soft drinks, and textile processes as well as other fine chemicals in a highly purified state. After John died Edmund took Arthur Albright into partnership and began making phosphorus at the Selly Oak works.[107]

Notable buildings

[edit]

- St Mary's Church

- Selly Oak Library

- Selly Oak Pumping Station

- Birmingham Battery and Metal Company

- Lodge Hill Cemetery, Birmingham

Notable people

[edit]- Christina Dony (1910-1995), English botanist and international hockey player

References

[edit]- ^ Morris, John (General Editor): Domesday Book 16 Worcestershire (Phillimore 1982) Land of William son of Ansculf: 23,1 Selly (Oak) and Bartley (Green); 23,5 Selly (Oak) held as two manors Robert holds from William

- ^ Maxam, Andrew (2004) Selly Oak & Weoley Castle on Old Picture Postcards: Reflections of a Bygone Age, (Yesterday's Warwickshire Series; No. 20); Introduction ISBN 1-900138-82-4)

- ^ Hooke, Della: The Anglo-Saxon Landscape – The Kingdom of the Hwicce (MUP 1985) p. 123

- ^ Hodder, Michael: Birmingham, the Hidden History (Tempus 2004) Chap 2

- ^ Taylor-Wilson, Robin and Proctor, Jennifer: Archaeological investigations at land off Sir Herbert Austin Way, Northfield (BWAS Transactions for 2013, Volume 117) p. 36

- ^ a b "Historic Environment Record". Archived from the original on 8 September 2012.

- ^ Hodder, Michael: Birmingham, the Hidden History (Tempus 2004) Chap 3

- ^ Muirhead, J H (Editor): Birmingham Institutions (Cornish Brothers, Birmingham 1911); Barrow, Walter: The Town and its Industries p4-5

- ^ Taylor-Wilson, Robin and Proctor, Jennifer: Archaeological investigations at land off Sir Herbert Austin Way, Northfield (BWAS Transactions for 2013, Volume 117) p. 37

- ^ Brassington, W Salt: Historic Worcestershire (Midland Educational Company Ltd 1894) pp21-30

- ^ Hooke, Della: The Landscape of the Staffordshire Hoard (Unpublished article 2010)

- ^ Gelling, Margaret: Signposts to the Past (Phillimore 1997) p155

- ^ VCH Worcestershire Volume 1: Pall Mall 1901 reprinted 1971 p. 279

- ^ Morris, John (general Editor) Domesday Book 16 Worcestershire (Chichester 1982) 23, 1; 23, 5

- ^ Morris, John (General Editor): Domesday Book 24 Staffordshire (Phillimore 1976) Land of the Bishop of Chester 2,16 Lichfield and its dependencies 2,22 Lichfield includes Harborne

- ^ Showell, Walter: Dictionary of Birmingham (Walter Showell and Sons 1885) p189

- ^ Greenway, Diane (Translated by) Henry of Huntingdon: The History of the English People 1000-1154 (OUP 2002) p. 46

- ^ Calendar of Close Rolls, 16 Edward II (1323) Membrane 13

- ^ Morris, John: Domesday Book 23 Warwickshire (Phillimore 1976)

- ^ a b Axinte, Adrian: Mapping Birmingham’s Historic Landscape (Birmingham City Council 2015) p5

- ^ Morris, John: Domesday Book 24 Staffordshire (Phillimore 1976)

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) p. 246

- ^ Willis Bund, J W and Amphlett, J (editors): Lay Subsidy Roll for the County of Worcester c1280 (WHS 1893) https://archive.org/stream/laysubsidyrollfo00greauoft#page/16/mode/2up

- ^ http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/taxatio/db/taxatio/printbc.jsp?benkey=WO.WO.DR.02 [dead link]

- ^ Eld, Reverend F J: Lay Subsidy Roll for the County of Worcester 1 Edward III (WHS 1895) https://archive.org/stream/worcestersubedward00greauoft#page/n5/mode/2up

- ^ "European Severe Weather Database". www.eswd.eu.

- ^ Morris, John (General Editor): Domesday Book 16 Worcestershire (Phillimore 1982) Land of William son of Ansculf: 23,1 Selly (Oak) and Bartley (Green); 23,5 Selly (Oak) held as two manors, Robert holds from William.

- ^ Leonard, Francis W: The Story of Selly Oak (St Mary’s Parochial Church Council 1933) p22 online at http://www.users.waitrose.com/~stmarysellyoak/History/The%20Story%20of%20Selly%20Oak.pdf

- ^ Morris, John (General Editor): Domesday Book 16 Worcestershire (Phillimore 1982) Land of William son of Ansculf: 23,1 Selly (Oak) and Bartley (Green).

- ^ Pearson, Wendy; and Surman, Maureen: Bartley Green and District through time (Amberley 2012) p54

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) pp21-22

- ^ WRO Ref 123 Ba 637, Bartley Green area transferred from Northfield Petty Sessional Division to Parish of Illey, Halesowen Petty Sessional Division

- ^ 'Parishes: Northfield', in A History of the County of Worcester: Volume 3 (London, 1913), pp. 194-201 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/worcs/vol3/pp194-201 [accessed 3 July 2015].

- ^ a b Tithe Map and Apportionments of Northfield Parish, Worcestershire 1839

- ^ Morris, John (General Editor): Domesday Book 16 Worcestershire (Phillimore 1982) Land of William son of Ansculf: 23,2 Northfield

- ^ Morning Chronicle: Sale of the Manor of Northfield and Weoley (11/8/1820 issue 16003)

- ^ Extent of the Manors of Dudley, Weley, and Cradley, on the death of Roger de Someri, Inq.pm 1 Edward 1: https://archive.org/stream/inquisitionespos00greauoft#page/n59/mode/2up

- ^ "Parishes: Northfield | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk.

- ^ Caswell, Pauline: Northfield (Stroud 1996) Introduction and p 112

- ^ Hampson, Martin: Northfield Volume II (Tempus 2003) p29

- ^ Pearson, Wendy; and Surman, Maureen: Bartley Green and District through time (Amberley 2012) p14

- ^ Walker, Peter L (Editor): Tithe Apportionments of Worcestershire, 1837-1851 (Worcestershire Historical Society 2011)

- ^ Hemingway, John: An Illustrated Chronicle of the Castle and Barony of Dudley 1070-1757 pp118-119

- ^ Demidowicz, G and Price S: King’s Norton – A History (Phillimore 2009)p. 153–155

- ^ Local Government Provisional Order (No 13) Bill.

- ^ Briggs, Asa: History of Birmingham, Volume II, Borough and City 1865-1938 (OUP 1952) Chapter 5

- ^ Manzoni, Herbert J: Report on the Survey –Written Analysis (Birmingham City Council 1952) p7

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964)Editorial note and p. 3.

- ^ a b HEAS: Archaeological Excavation at Goodman’s Yard, Selly Oak, Birmingham, Project 2521, Report 1255, BSMR 20726 (Worcestershire County Council 2004)

- ^ White, Reverend Alan: The Worcester and Birmingham Canal – Chronicles of the Cut (Brewin 2005) p. 308

- ^ a b Pearson, Wendy: Selly Oak and Bournbrook through time (Amberley 2012) p. 30

- ^ Pearson, Wendy: Selly Oak and Bournbrook through time (Amberley 2012) p. 38

- ^ a b Maxam, Andrew (2004) Selly Oak & Weoley Castle on Old Picture Postcards: Reflections of a Bygone Age, (Yesterday's Warwickshire Series; No. 20); caption 19 ISBN 1-900138-82-4)

- ^ White, Reverend Alan: The Worcester and Birmingham Canal, Chronicles of the Cut (Brewin 2005)

- ^ "Lapal Canal Trust Latest News 13 April". Lapal Canal Trust. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ Butler, Joanne; Baker, Anne; Southworth, Pat: Selly Oak and Selly Park (Tempus 2005) p.46

- ^ Maxam, Andrew (2004) Selly Oak & Weoley Castle on Old Picture Postcards: Reflections of a Bygone Age, (Yesterday's Warwickshire Series; No. 20); caption 25 ISBN 1-900138-82-4)

- ^ Dowling, Geoff; Giles, Brian; and Hayfield, Colin (1987) Selly Oak Past and Present: a Photographic Survey of a Birmingham Suburb. Department of Geography, University of Birmingham; p. 2

- ^ Baker, Anne; Butler, Joanne; and Southworth, Pat (2002) 'How Did The Oak Get into Selly', in: Birmingham Historian, Issue 23, October 2002, p. 7 Birmingham & District Local History Association ISSN 0953-7090

- ^ Leather, Peter, 'Old Oak Gives Up Secrets', Birmingham Evening Mail, 7 June 2001, p. 9

- ^ The Statutes at Large, of England and of Great-Britain: From Magna Carta to the Union of the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. VIII, p. 831 (1811)

- ^ Page, William and Willis-Bund, J. W. (eds) (1913) Victoria County History of The Counties of England: a History of Worcestershire, Vol. III., p. 194 Institute of Historical Research, University of London

- ^ Leonard, Francis W., The Story of Selly Oak Birmingham, p. 2 (St Mary's Parochial Church Council, 1933)

- ^ Butler, Joanne, Baker, Anne and Southworth, Pat, 'Back to roots: Dates don't support Selly witch theory', Birmingham Evening Mail, January 2001

- ^ Snape, John 'Plan of the Intended Navigable Canal from Birmingham to Worcester', 1789

- ^ 'Putting the oak in Selly Oak', Birmingham Evening Mail, 29 March 1985

- ^ 'From a great oak - a little sapling is set to grow', Birmingham Evening Mail, 14 October 2000

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) pp. 512, 527, 530, 534, 537, 538, 542

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Selly Oak and Weoley Castle on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) image 21

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964)pp. 430–32

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Selly Oak and Weoley Castle on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) image 9

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Selly Oak and Weoley Castle on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) image 10

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Selly Oak and Weoley Castle on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) image 8

- ^ The King’s Norton Web Site: Timeline - Poor Laws, Workhouses, and Social Support Archived 13 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Rossbret Institutions Website|: Kings Norton Workhouse". Archived from the original on 5 December 2009.

- ^ Butler, Joanne; Baker, Anne; Southworth, Pat: Selly Park and Selly Oak (Stroud 2005) pp. 88–91

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964 p349)

- ^ Pearson, Wendy: Selly Oak and Bournbrook through time (Stroud 2012) pp. 76–781

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Selly Oak and Weoley Castle on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) image 5

- ^ Dowling, Geoff; Giles, Brain; and Hayfield, Colin: Selly Oak Past and Present: A Photographic Survey of a Birmingham Suburb (Department of Geography, University of Birmingham 1987) p7

- ^ Dowling, Geoff; Giles, Brain; and Hayfield, Colin: Selly Oak Past and Present: A Photographic Survey of a Birmingham Suburb (Department of Geography, University of Birmingham 1987) p4

- ^ Dowling, Geoff; Giles, Brain; and Hayfield, Colin: Selly Oak Past and Present: A Photographic Survey of a Birmingham Suburb (Department of Geography, University of Birmingham 1987) p36

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Selly Oak and Weoley Castle on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) image 23

- ^ White, Reverend Alan: The Worcester and Birmingham Canal – Chronicles of the Cut.(Brewin p. 311)

- ^ Butler, Joanne; Baker, Anne; Southworth, Pat: Selly Oak and Selly Park (Tempus 2005) p105

- ^ Butler, Joanne; Baker, Anne; Southworth, Pat: Selly Oak and Selly Park (Tempus 2005) p103

- ^ a b Maxam, Andrew: Stirchley, Cotteridge, and Selly Park on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) image 49

- ^ Marks, John: Birmingham Inns and Pubs (Reflections of a Bygone Age 1992) p31

- ^ White, Reverend Alan: The Worcester and Birmingham Canal – Chronicles of the Cut(Brewin) p. 311

- ^ Marks, John: Birmingham Inns and Pubs (Reflections of a Bygone Age 1992) p28

- ^ Showell, Walter: Dictionary of Birmingham (Walter Showell and Sons 1885) p81

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Selly Oak and Weoley Castle on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) image 47

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Selly Oak and Weoley Castle on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) image 46

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Selly Oak and Weoley Castle on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) image 60

- ^ Dowling, Geoff; Giles, Brain; and Hayfield, Colin: Selly Oak Past and Present: A Photographic Survey of a Birmingham Suburb (Department of Geography, University of Birmingham 1987) p39

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) pp. 354–485

- ^ Dowling, Geoff; Giles, Brain; and Hayfield, Colin: Selly Oak Past and Present: A Photographic Survey of a Birmingham Suburb (Department of Geography, University of Birmingham 1987) p33

- ^ Dowling, Geoff; Giles, Brain; and Hayfield, Colin: Selly Oak Past and Present: A Photographic Survey of a Birmingham Suburb (Department of Geography, University of Birmingham 1987) p26

- ^ Pearson, Wendy: Selly Oak and Bournbrook through time (Amberley 2012) p13

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) p. 207

- ^ White, Reverend Alan: The Worcester and Birmingham Canal – Chronicles of the Cut (Brewin 2005) p. 319

- ^ Showell, Walter: Dictionary of Birmingham (Walter Showell and Sons 1885) p324

- ^ Showell, Walter: Dictionary of Birmingham (Walter Showell and Sons 1885) p326

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) pp. 133, 159–60, 191

- ^ White, Reverend Alan: The Worcester and Birmingham Canal – Chronicles of the Cut ( Brewin 2005) pp. 292, 293

- ^ White, Reverend Alan: The Worcester and Birmingham Canal – Chronicles of the Cut ( Brewin 2005) p. 310

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) p. 129

Bibliography

[edit]- Brassington, W Salt (1894). Historic Worcestershire. Midland Educational Company Ltd.

- Briggs, Asa (1952). History of Birmingham, Volume II, Borough and City 1865-1938. OUP.

- Butler, Joanne; Baker, Anne; Southworth, Pat (2005). Selly Oak and Selly Park. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3625-2.

- Chew, Linda and Anthony (2015). TASCOS: The Ten Acres and Stirchley Co-Operative Society, A Pictorial History.

- Chinn, Carl (1995). One Thousand Years of Brum. Brewin Books. ISBN 0-9534316-5-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Demidowicz, George (2015). 'Selly Manor' The manor house that never was.

- Dowling, Geoff, Giles, Brian and Hayfield, Colin (1987). Selly Oak Past and Present: A Photographic Survey of a Birmingham Suburb. Department of Geography, University of Birmingham. ISBN 0-7044-0912-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Doubleday H Arthur (Editor) University of London Institute of Historical Research (1971). VCH Worcestershire Volume 1. Dawson's of Pall Mall. ISBN 0-7129-0479-4.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Gelling, Margaret (1997). Signposts to the Past. Phillimore. ISBN 978-186077-592-5.

- Hodder, Michael (2004). Birmingham, The Hidden History. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3135-8.

- Hooke, Della (1985). The Anglo-Saxon Landscape, The Kingdom of the Hwicce. MUP.

- Hutton, William (1839). An History of Birmingham. Wrightson and Webb, Birmingham.

- Leonard, Francis W (1933). The Story of Selly Oak. ST Mary’s PCC.

- Lock, Arthur B. History of King's Norton and Northfield Wards. Midland Educational Company Ltd.

- Manzoni, Herbert J (1952). Report on the Survey –Written Analysis. Birmingham City Council.

- Marks, John (1992). Birmingham Inns and Pubs. Reflections of a Bygone Age. ISBN 0-946245-51-7.

- Maxam, Andrew (2004). Selly Oak and Weoley Castle on old picture postcards. Reflections of a Bygone Age. ISBN 1-900138-82-4.

- Maxam, Andrew (2005). Stirchley, Cotteridge, and Selly Park on old picture postcards. Reflections of a Bygone Age. ISBN 1-905408-01-3.

- Page, William (Editor) University of London Institute of Historical Research (1971). VCH Worcestershire Volume 2. Dawson's of Pall Mall.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Pearson, Wendy (2012). Selly Oak and Bournbrook through time. Amberley. ISBN 978-1-4456-0237-0.

- Pugh, Ken (2010). The Heydays of Selly Oak Park 1896-1911. History into Print. ISBN 978-1-85858-336-5.

- Showell, Walter (1885). Dictionary of Birmingham. Walter Showell and Sons.

- Stevens, W B, ed. (1964). VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham. OUP.

- Thorn, Frank and Caroline (1982). Domesday Book 16 Worcestershire. OUP. ISBN 0-85033-161-7.

- Tithe Map and Apportionments of Northfield Parish, Worcestershire. 1839.

- Walker, Peter L, ed. (2011). Tithe Apportionments of Worcestershire, 1837-1851. Worcestershire Historical Society.

- White, Reverend Alan (2005). The Worcester and Birmingham Canal – Chronicles of the Cut. Brewin. ISBN 1-85858-261-X.

- Willis Bund, J W and Amphlett, J (editors). Lay Subsidy Roll for the County of Worcester c1280 (WHS 1893).

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- Birmingham Post article about the demolition of the Birmingham battery

- 1884 Ordnance Survey 25" map of Selly Oak (404 ERROR)

- A Brief History of Selly Oak

- St Mary's Parish Church, Selly Oak (includes PDF version of Francis W. Leonard's The Story of Selly Oak)

- An old colour photograph from 1957 of Selly Oak Village

- More Photos of Selly Oak (includes one of the plaque on the stump of the original Selly Oak)

- Excavations of lime kilns at Selly Oak

- Restoration of Selly Oak to Lapal canal, Selly Oak section

- Selly Oak New Road (Birmingham City Council website)

- Birmingham, B29

- Selly in the Domesday Book