Seraglio

A seraglio,[a] serail,[b] seray or saray (from Persian: سرای, romanized: sarāy, lit. 'palace', via Turkish, Italian and French) is a castle, palace or government building which was considered to have particular administrative importance in various parts of the former Ottoman Empire.

"The Seraglio" may refer specifically to the Topkapı Palace, the residence of the former Ottoman sultans in Istanbul (known as Constantinople in English at the time of Ottoman rule).[1] The term can also refer to other traditional Turkish palaces (every imperial prince had his own) and other grand houses built around courtyards.

Etymology

[edit]The term seraglio, from Italian,[2][3][4] has been used in English since 1581.[5] The Italian Treccani dictionary gives two derivations:[4]

- one via Turkish: seray or saray[2][6] (with the variants seraya or saraya), which comes from Persian: سرای, romanized: sarāy, lit. 'palace'[3] or, per derivation, the enclosed court for the wives and concubines of the harem of a house or palace (see § Harem);

- the other — in the sense of enclosure[c] — from Late/Medieval Latin: serraculum, derived from Classical Latin serare, lit. 'to close', which comes from sera, lit. 'door-bar'.[7][8]

The term may also be spelt serail, via French influence, based on the Italian term.[3]

Harem

[edit]

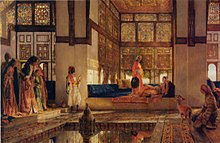

Since the Topkapı Palace's harem (commonly known as "The Seraglio harem"[9]) grew in prominence and fame, the term saray/serail/seraglio began also being commonly used as a synonym of harem, the sequestered living quarters used by wives and concubines in an Ottoman household.[d][9]

In Ottoman culture

[edit]

Besides the Topkapı Palace ("The Seraglio"), the most famous seray is the Grand Serail of Beirut (Arabic: السراي الكبير, romanized: Al-Sarāy al-Kabir) in Lebanon, which is the headquarters of the prime minister. It is situated atop a hill in downtown Beirut a few blocks away from the Lebanese Parliament. The hill was the site of an Ottoman army base from the 1840s, which was built up, fortified, and expanded in the 1850s. At first it was known as al quishla, from the Turkish word kışla, meaning barracks.

Other examples include:

- the Grand Serail of Aleppo, in Syria; a French construction inspired to the Ottoman tradition.

- the Red Serail of Tripoli, in Libya. Located in central Tripoli, it also houses a museum.

- the new presidential palace of Turkey, completed in 2014, popularly called Ak Saray ("White Palace").

Seventeen saraya were established in Palestine during Ottoman rule; most were established by regional officials and their families such as the Ridwan dynasty and Zahir al-Umar and his family.[10]

In Italy

[edit]In modern Italian the word is spelled serraglio. It may refer to a wall or structure, either for defence — such as the Serraglio of Villafranca di Verona, a defensive wall built by the Scaligeri — or for containment, for example of caged wild animals.[c][4] The ghettoes established in many Italian cities following the promulgation by Pope Paul IV in 1555 of the papal bull Cum nimis absurdum were initially called serraglio degli ebrei, lit. 'enclosure of the Jews'.[11]

Seraglio is also the name of the artificial island on which Mantua is located.

In literature and the arts

[edit]In the context of the turquerie fashion, the seraglio became the subject of works of art, the most famous perhaps being Mozart's 1782 Singspiel, Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio), based on Christoph Friedrich Bretzner's 1781 libretto Belmont und Constanze, oder Die Entführung aus dem Serail (Belmonte and Konstanze, or The Abduction from the Seraglio). In Montesquieu's 1721 Persian Letters, one of the main characters, a Persian from the city of Isfahan, is described as an occupant of a seraglio.

Homophones

[edit]Saraya is also used as a military unit title in the Arab world. In this case the Arabic is سرية, a different word from "saraya" (السرايا) as in a building. The etymology is also different from the building: سرية is from Arabic and communicates the idea of a "private group". However the plural is سرايا (saraya), indistinguishable from the term "saraya" which is a variant (in the singular) of saray (the building).

The normal translation for سرية is company (military unit), but in the case of the Lebanese Resistance Saraya the term is often arbitrarily translated as brigades.

Another example is the Syrian Defense Saraya.

See also

[edit]- Caravanserai, another word involving saray, is an inn or rest stop for caravans

- Sarayburnu (also known as Seraglio Point)

- Grand Serail in Beirut, Lebanon, now the office of the prime minister of Lebanon

- The Abduction from the Seraglio, opera singspiel by Mozart

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ IPA: /səˈrɑːljoʊ/ sə-RAH-lyoh, US also /səˈræljoʊ/ sə-RAL-yoh.

- ^ IPA: /səˈraɪ, səˈreɪl/ sə-RY, sə-RAYL.

- ^ a b Traditionally an enclosure for wild animals, but also as a synonym of ghetto, for example in Italy.

- ^ The term harem is a generic term for domestic spaces reserved for women in a Muslim family, which can also refer to the women themselves.

References

[edit]- ^ "Topkapi Palace Museum – museum, Istanbul, Turkey". Archived from the original on 24 February 2021.

- ^ a b "seraglio". The Free Dictionary. Farlex. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Harper, Douglas. "seraglio". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ a b c "Serraglio". Treccani: Vocabolario on line (in Italian). Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Kahf, Mohja. Western Representations of the Muslim Woman. University of Texas Press. p. 5.

- ^ "seraglio". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ ""sĕra", entry from Lewis & Short". Latin Word Study Tool. Retrieved 3 November 2022 – via Perseus.

- ^ Macdonald, A. M., ed. (1972). Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary. London: Chambers. p. 1235. ISBN 055010206X.

- ^ a b "Harem". Allaboutturkey.com. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Bshara, Khaldun. "The Ottoman Saraya: All That Did Not Remain". Jerusalem Quarterly. 69: 66.

- ^ Debenedetti-Stow, Sandra (1992). "The Etymology of "Ghetto": New Evidence from Rome". Jewish History 6 (1/2), The Frank Talmage Memorial Volume: 79–85 (subscription required)

Bibliography

[edit]- Freely, John (1999). Inside the Seraglio: Private Lives of the Sultans in Istanbul.