Belmont–Paul Women's Equality National Monument

Belmont–Paul Women's Equality National Monument; formerly Sewall–Belmont House and the Alva Belmont House | |

Belmont-Paul Women's Equality National Monument (Sept. 2021) | |

| Location | 144 Constitution Avenue NE Washington, D.C. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°53′31″N 77°0′13″W / 38.89194°N 77.00361°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1800 |

| Website | Belmont–Paul Women's Equality National Monument |

| NRHP reference No. | 72001432 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 16, 1972[1] |

| Designated NHL | May 30, 1974[2] |

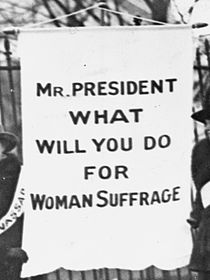

The Belmont–Paul Women's Equality National Monument (formerly the Sewall House (1800–1929), Alva Belmont House (1929–1972), and the Sewall–Belmont House and Museum (1972–2016)) is a historic house and museum of the U.S. women's suffrage and equal rights movements located in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Washington, D.C. The monument is named after suffragists and National Woman's Party leaders Alva Belmont and Alice Paul.

Since 1929 the house has served as headquarters of the National Woman's Party, a key political organization in the fight for women's suffrage. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972, designated a National Historic Landmark in 1974. From 1972 to 2016, the Sewall–Belmont National Historic Site was an affiliated unit of the National Park Service. In 2016, President Barack Obama designated it a national monument.

Sewall House history

[edit]Construction of the house

[edit]On June 20, 1632, Charles I, King of England, made a land grant in North America to Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore which became the Province of Maryland (later the state of Maryland).[3] Lord Baltimore established counties within the province, and provincial courts further subdivided counties into areas known as hundreds. One of these was New Scotland Hundred. Its southern boundary was the Potomac River, extending from the mouth of Oxon Creek upstream to Little Falls Rapids (a point 10 miles (16 km) downstream from the Great Falls of the Potomac River). On February 12, 1663, the third Lord Baltimore granted a land patent of 1,000 acres (4.0 km2) in New Scotland Hundred to George Thompson. The property (which was now called Duddington Manor) changed hands, was subdivided, and inherited a number of times before it came into the possession of nine-year-old Daniel Carroll in 1773.[4]

On July 9, 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which approved the creation of a national capital on the Potomac River. The exact location was to be selected by President George Washington. About December 1790, Washington chose the site now known as the District of Columbia. Congress ratified his decision in 1791.[5] Congress subsequently purchased all land in the new district from its private owners (the "original patentees"), including Carroll. The district was divided into squares, and each square into lots. Daniel Carroll purchased lot 1 in square 725 on October 18, 1793, for $266.66, (~$6,075 in 2023) and the same day the federal government gave lot 32 in square 725 back to Carroll gratis. Robert Sewall purchased lot 2 in square 725 for $429.33 on October 18, and lots 1 and 32 from Carroll for $600.29 on January 29, 1799.[6][7]

The construction of the main house occurred in 1799 and 1800.[8][9] The architect of the new Sewall house is unknown, but research by the Historic American Buildings Survey indicates it was probably Leonard Harbaugh, an architect from Baltimore, Maryland, who was just beginning a notable career. (His design for the United States Capitol was the first chosen and later rejected by Congress, and he later designed Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Georgetown; Old North, the first building on the campus of Georgetown University; the original Treasury Building; and the War Office Building, which was later replaced by the Executive Office Building).[10] The main house was essentially an addition to the front of a one-room farmhouse[8] believed to date from 1750.[7][11] Although the Sewall family rarely occupied the home, its size, beauty, and location led many prominent government leaders to reside there. These included Albert Gallatin, who served as Secretary of the Treasury under Thomas Jefferson and James Madison,[8] and Reverdy Johnson, U.S. Senator from Maryland, United States Attorney General, and U.S. Minister to the United Kingdom.[9]

Tradition maintains that British troops set fire to the house during the War of 1812, and that gunfire from within or behind the Sewall residence provoked the attack.[12][13]

History of the house in the 1800s

[edit]The house has undergone several architectural changes and restorations.[14] After the house was partially burned by the British in 1814, Sewall sought reimbursement from the federal government for the damages. Congress declined to award them,[15] so Sewall himself paid to have the structure repaired in 1820. A stable was probably added to the property at this time.[9] Sewall died in the house on December 16, 1820, leaving the building to his wife, Polly, and his four surviving daughters.[16] It is unclear which of these continued to live in the house, but Susan definitely lived in it until her death in 1837. Her will left the house to her older brother, Robert Darnell Sewall. Robert Sewall died on March 18, 1853, and bequeathed the house to his nieces, Susan and Ellen Daingerfield (his sister Susan's daughters).[17] In 1879, the Daingerfields made a major alteration to the house by added a half mansard roof to the front.[9] In 1865, Susan Daingerfield married John S. Barbour, Jr., a railroad executive who later became a U.S. Senator from Virginia. After Susan's death in 1886, Barbour continued to live in the Sewall house with his sister-in-law, Ellen.[18]

Sewall House was empty from Ellen Daingerfield's death in 1912 until 1922,[18] when it was purchased by Senator Porter H. Dale of Vermont.[19] Dale extensively rehabilitated the house from 1922 to 1924. He renovated the porch at the rear of the house and enclosed it, added three bathrooms, laid new floors throughout the structure, added three windows on the first floor on the west side of the house, and renovated the kitchen.[9] Architect J.G. Herbert of Washington, D.C., oversaw these changes.[20]

Alva Belmont House history

[edit]Becoming National Woman's Party headquarters

[edit]

On May 8, 1921, the National Woman's Party (NWP) announced it had purchased the Old Brick Capitol, a historic red brick structure built in 1815 by Congress as a temporary site for the national legislature until the United States Capitol (burned during the War of 1812) could be rebuilt. The organization planned to offer a library, reading rooms, sleeping quarters, meeting rooms, and a dining facility at their new headquarters, which replaced temporary facilities on Lafayette Square.[21] The organization obtained the structure for $150,000, and spent another $50,000 repairing and upgrading it.[22][23] The headquarters were dedicated on May 21, 1922.[24]

However, in 1902, the U.S. Senate Park Commission issued its recommendations for the development of the national capital. This report, The Report of the Senate Park Commission. The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia (better known as the McMillan Plan after the commission's chairman, Senator James McMillan) had recommended clearing nearly all the area around the U.S. Capitol building and erecting a cluster of government office buildings here. This included a new United States Supreme Court Building.[25] In 1926, Congress enacted the Public Buildings Act, which provided for land purchase and construction of the Federal Triangle complex of government office buildings between the National Mall and Pennsylvania Avenue NW. Half the funding in the act, however, provided for construction of a new Supreme Court building across 1st Street NE from the U.S. Capitol.[26]

The site for the new court structure was the site of the Old Capitol Building. Eminent domain proceedings began swiftly. In 1927, fearing the NWP might lose its headquarters, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, the NWP's wealthy benefactor and co-founder, paid Senator Dale $100,000 (~$1.41 million in 2023) in cash for an option to purchase the Sewall house.[20][27][28][a] The condemnation proceedings went against the party. Although they were initially offered only $100,000 for their property, the NWP protested.[30] In November 1928 the National Woman's Party accepted an award of $299,200 (~$4.2 million in 2023) for their existing headquarters in the Old Capitol Prison.[22][30][31]

Belmont exercised her option and obtained title to the Sewall house on May 21, 1929.[20] The party announced their purchase of the structure in early September 1929.[32]

Renovations to the Belmont House

[edit]The structure was renamed the Alva Belmont House during the NWP's national convention, which opened on December 6, 1929.[33] Renovations to the structure began in August 1929. It is unclear if Columbus, Ohio, architect Florence Kenyon Hayden Rector or local D.C. decorator Madeleine McCandless designed and implemented the changes, but the Historic American Buildings Survey concludes that McCandless probably oversaw the improvements. These included a new window and door in the first floor on the east side, double doors in the west side, a new window on the second floor on the east side, a new bathroom on the second floor, and a new window on the second floor on the west side.[20] These renovations cost about $30,000. Additionally, the NWP purchased two additions to the site at a total cost of about $19,000 to $20,000.[27] When the Old Capitol was demolished, women from the NWP showed up with wheelbarrows to rescue bricks from the structure, which they then used to pave the patio in the Belmont House garden.[34] A bronze plaque was affixed to the exterior of the house after the renovations were complete in December 1930, marking the official dedication of Alva Belmont House.[35] The renovations converted the private residence to a multipurpose living and working space where NWP's leader and main strategist, Alice Paul, and others lived and worked.

In 1955, the U.S. Senate considered legislation that would permit the condemnation of Belmont House so that underground security vaults could be constructed there as part of the construction of the Dirksen Senate Office Building. But the plan met stiff opposition from local residents and the Capitol Hill Restoration Society.[36] The battle over the legislation continued into 1958.[37]

In 1960, Congress enacted legislation exempting Sewall–Belmont House from property taxation.[38][39]

In 1965, by Senator Stephen M. Young introduced legislation in Congress to purchase the Sewall–Belmont House and turn it into a residence for the Vice President of the United States. Hearings were held on the bill in 1966, which provided $450,000 for purchase of the structure and property and $200,000 for renovations and additions. But opponents argued that the house was not large enough and not remote enough from the Capitol to provide privacy, and the bill died.[40]

Demolition threat

[edit]

In 1966, the Senate began deliberations which led to construction of the Hart Senate Office Building. The Dirksen Senate Office Building occupied the western half of the block bounded by 1st Street NE, Constitution Avenue NE, 2nd Street NE, and C Street NE. The Architect of the Capitol and Senators sought to condemn the entire eastern half of the block. The Belmont–Paul House sat on the southeast corner of this area. The stand-alone legislation authorizing condemnation of the buildings on the site exempted the Belmont–Paul (then Sewall–Belmont) House from demolition, but not the two adjacent buildings which it used as apartments for its members when visiting Washington over many decades to organize and lobby on behalf of all aspects of Women's Equality.[41][42] Architects wanted this land for an entrance to a planned underground parking garage.[43] This legislation cleared the Senate Committee on Public Works in October 1967.[41] The full Senate approved the bill on April 30, 1968.[44]

The House Committee on Public Works approved the bill on May 22, 1968.[45] The full House of Representatives balked at passing the bill. Architectural historian L. Morris Leisenring had studied the Belmont–Paul House for the Architect of the Capitol, and concluded that the two adjacent structures had once been slave quarters and a tobacco barn, and warranted preservation. Leisenring had recently overseen the restoration of Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, and his opinion persuaded many House members that the entire NWP complex should be saved.[42] But other historians disputed Leisenring's conclusions.[39] Opponents of the bill were also angered by the cost of the Senate building and actions taken by the Senate previously that year. The House refused to act on the bill, and it died when the 90th Congress ended on January 3, 1969.[46]

Changes to the architectural design of the building moved the parking garage entrance to the northern side of the proposed structure, which left the government seeking to condemn the NWP's two outbuildings for use as greenspace. To overcome House resistance to its authorization legislation, the Senate attached language authorizing the land condemnation to a bill which had already passed the House. During conference committee meetings, House members were unable to have the offending amendment removed from the bill. It passed the House and Senate, and became law.[47]

Post-1970s renovations

[edit]In 1974, Congress voted to provide the National Woman's Party with $300,000 (~$1.44 million in 2023) in historic preservation funds to help renovate and maintain the house. The legislation also authorized the National Park Service to conduct tours of the site.[48] But major budget cuts enacted the following year jeopardized these funds,[49] and the Historic American Buildings Survey has concluded that they never occurred.[50]

In 1984, Congress enacted legislation which once more gave the NWP historic preservation funding for the house.[51]

The Sewall–Belmont House continued to be used as the headquarters for the National Woman's Party into the 21st century.[52] Over time, the house also became a museum that housed an archive, memorabilia, documents, furniture, and artwork related to the women's suffrage and equal rights movement.[19] Maintaining the structure proved increasingly costly,[53] so the organization began renting the Sewall–Belmont House as a meeting center and wedding site.[citation needed] At their peak in 2007, weddings brought in more than $100,000 (~$141,598 in 2023) for the museum. The discovery of mold in the Florence Bayard Hilles Research Library in 2014 forced the museum to spend $75,000 (~$95,088 in 2023) to remove it. To pay for the repair, the museum placed two of its three staff people on half-time. In January and February 2016, heavy snowfall damaged copper gutters at the house, forcing the museum to cancel most of its Women's History Month programming to pay for repairs.[54]

2022 renovation

[edit]Starting in January 2022, the National Monument was closed down to the public to begin a renovation. Funded through the Great American Outdoors Act (GAOA), the restoration includes installation of new HVAC equipment throughout the house, rehabilitation of all historic windows, installation of a new metal roof, an extension of fire sprinkler protection to the Library, plaster wall/ceiling & crack repairs, lead paint abatement, structural flooring repairs, and increased storm water drainage capacity in the backyard.[55] It reopened in August 2023.

Historic designations

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

The Belmont–Paul House is the oldest house still standing in the Capitol Hill neighborhood.[56][7][52] Although formally dedicated as the Alva Belmont House by the NWP in 1931, the combined name Sewall–Belmont House came into usage by The Evening Star newspaper as early as 1942,[57] and by The Washington Post in 1974.[58]

The Sewall–Belmont House was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972, and declared a National Historic Landmark in 1974.[2][59][60]

In August 2015, Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-Maryland) introduced legislation to authorize the National Park Service to accept ownership of the Sewall–Belmont House should the National Woman's Party agree to transfer it at no cost. The National Woman's Party found the building increasingly costly to maintain, and the transfer of title would allow for better conservation of the site.[61]

President Barack Obama designated the Sewall–Belmont House a national monument on April 12, 2016.[53][54] The house, renamed Belmont–Paul Women's Equality National Monument after Alva Belmont and Alice Paul, continues to house the National Woman's Party collection, which includes an extensive library on women's suffrage and women's issues, the NWP archive, and museum holdings such as art, memorabilia, and exhibits. Financier David Rubenstein also announced he would make a $1 million donation to the National Park Foundation to help restore and conserve the house and support its ongoing mission.[53] Renting the site for weddings ended, NWP officials said.[54] L. Page Harrington, executive director of the museum, said the museum and NWP archives will continue to use the name National Woman's Party.[54]

Architecture

[edit]

When construction on the Sewall House was completed in 1800, the house was in the Adam Federal style of architecture.[62] The Historic American Buildings Survey has concluded that the structure has been so modified over the years that it no longer belongs to a single architectural style but, rather, reflects as many as seven different genres.[62] Other sources agree that the building no longer has a definable architectural style,[63] but most feel it has retained enough features to still be characterized as Federal,[64][65][66][67] while some feel it is more in the Georgian style.[68]

The rectangular home is 58 feet (18 m) long on the south side and 130 feet (40 m) long on the west side. The look-out basement is only about a third below-ground. The main building consists of two and a half stories.[62] The roof was gabled,[69] although this was changed to a partial mansard roof in 1879.[9] The house is made of brick laid primarily in Flemish bond, although some areas are laid in English bond and American bond and some have no particular pattern. The principal facade, which faces Constitution Avenue, is three bays wide. The front door features sidelights and an overhead fanlight in a "peacock" design. A molded semicircular arch with keystone surmounts the fanlight. Paired stairs lead to a landing before the main entrance, while the basement is accessed by a door below the landing. A round brick arch doorway provides access to the below-landing space.[62]

A 1+1⁄2-story kitchen addition is attached to the northeast corner of the house on the north side. A one-story stable (which now serves as a library) is attached to the north side of the kitchen addition. These are 19th century additions to the structure. A 20th century addition, on the west side of the kitchen, forms an enclosed terrace. This terrace addition reaches to the south wall of the stable/library, helping to create and enclose the hall between the two additions.[62]

The double-hung windows on the principal facade on the first and second floors consist of a main panel three by three rectangular panes wide, with sidelight panels two over two vertical rectangular pane wide. Mullions divide the three panels. Each of these windows has a stone lintel with a circular bas-relief design in the corner, and false shutters. In the mansard roof at the front of the house are three gabled dormers. Each dormer is surrounded by decorative millwork with two dentils below, square Tuscan pillars with indents on either side, a lintel with the circular bas-relief, and a plain triangular pediment.[69]

Original windows on the other facades are double-hung, with main panels three by three rectangular panes wide. Each of these also has a stone lintel with circular bas-relief design. Windows added later lack the lintel.

The interior floor plan is typical of an Adam Federalist house, with a center hall and two symmetrical rooms on either side. The third (or attic) floor consisted of a secondary suite, with kitchenette and full bathroom.[69] Over the kitchen addition were two floors, each only three-quarters normal height. A narrow, spiral servants' stairs provides access to a bedroom and full bath on each floor above.

Visiting the site

[edit]The Belmont–Paul Women's Equality National Monument is located at 144 Constitution Avenue NE.[8] The nearest Metro stop is Union Station.[70]

See also

[edit]- List of monuments and memorials to women's suffrage

- List of national monuments of the United States

- List of the oldest buildings in Washington, D.C.

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ According to Nettie Podell Odenburg, who assisted Belmont in her suffrage activities, Belmont originally favored the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Alice Paul wanted more militant action, but Odenburg opposed this. At the Association's 1915 convention, Genevieve Davis Bennett Clark, wife of Speaker of the House Champ Clark, spoke so long that she used up all of Belmont's time. Belmont was enraged. At this point, Paul and others—intent on breaking from the Association to form the National Woman's Party—approached Belmont as she left the dais and asked her to fund their efforts. Angry at how she'd been treated, Belmont agreed to buy a home for the NWP and provide it with an endowment to fund its efforts.[29]

- Citations

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b "Belmont–Paul Women's Equality National Monument formerly Sewall–Belmont House, Alva Belmont House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2012-10-11. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ Brugger 1996, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Shultz 1998, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Crew, Webb & Wooldridge 1892, pp. 89–92.

- ^ Shultz 1998, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Eberlein & Hubbard 1958, p. 425.

- ^ a b c d Fogle 2009, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e f Shultz 1998, p. 4.

- ^ Shultz 1998, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Shultz 1998, p. 2.

- ^ Fogle 2009, pp. 37–38.

- ^ McCavitt & George 2016, pp. 145–146, 151.

- ^ Caggiula & Brackett 2008, p. 16.

- ^ Shultz 1998, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Shultz 1998, p. 9.

- ^ Shultz 1998, p. 10.

- ^ a b Shultz 1998, p. 11.

- ^ a b Fogle 2009, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d Shultz 1998, p. 12.

- ^ "Get 'Watch Tower' For Woman's Party". The Washington Post. May 9, 1921. p. 8.

- ^ a b Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds 1931, p. 17.

- ^ "Harding Is To Attend Dedication By Women". The Washington Post. December 28, 1921. p. 4.

- ^ "National Woman's Party Dedicates New Home Opposite the Capitol". The Washington Post. May 22, 1922. p. 2; "Make Old Capitol Shrine For Women". The Washington Post. May 22, 1922. p. 2.

- ^ Gournay 2004, p. 118.

- ^ Gutheim & Lee 2006, p. 182.

- ^ a b Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds 1931, p. 13.

- ^ Evelyn, Dickson & Ackerman 2008, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Odenburg, Nettie Podell (May 28, 1972). "Alva Belmont's Place in Equal Rights". The Evening Star. p. D3.

- ^ a b "71 Accept Awards In Court Site Case". The Washington Post. December 6, 1928. p. 24.

- ^ "Site for New Court Priced at $1,768,741". The Washington Post. November 21, 1928. p. 22.

- ^ Usher, Marion E. (September 15, 1929). "The Feminists Capture a Landmark". The Washington Post. p. SM3.

- ^ "Women to Honor Mrs. Pankhurst". The Evening Star. October 1, 1929. p. 32.

- ^ Lide, Frances (April 13, 1960). "Alva Belmont House Toured". The Evening Star. p. 42.

- ^ "Senators to Aid at Belmont House". The Evening Star. December 28, 1930. p. 3.

- ^ "Senate Meets Opposition In Move to Raze Landmark". The Evening Star. May 29, 1955. p. 10.

- ^ Warren, Don S. (May 22, 1956). "Early Decision Due on Buying of Capital Land". The Evening Star. p. 13; "Capitol Seeks Additional Land". The Evening Star. June 7, 1956. p. 25; "Senate to Vote on Office Land". The Evening Star. January 1, 1958. p. C5.

- ^ Lindsay, John J. (January 20, 1960). "Usually Vocal Perle Shy Before Senators". The Washington Post. p. A2; Lindsay, John J. (April 12, 1960). "Battle Site, Car Finance Bills Passed". The Washington Post. p. B1.

- ^ a b "Belmont Plot Thickens". The Evening Star. September 19, 1968. p. D4.

- ^ "Belmont House on Tour". The Evening Star. May 12, 1972. p. D3; Shelton, Isabelle (February 20, 1966). "Bill Asks Home for Vice President on Grounds of Naval Observatory". The Sunday Star. pp. 1, 15; Shelton, Elizabeth (February 26, 1966). "VP House Far From Home". The Washington Post. p. B4.

- ^ a b "More Office Space For Senators Urged". The Washington Post. August 24, 1967. p. D23; "Senate Panel Backs Bill on Realty Purchase". The Evening Star. October 10, 1967. p. D4.

- ^ a b Shelton, Elizabeth (September 18, 1968). "Woman's Party Fights Congress to Save Home". The Washington Post. pp. D1, D6.

- ^ Shelton, Elizabeth (September 20, 1968). "Belmont House Backers Get Reprieve". The Washington Post. p. C1.

- ^ "City Life: Senate Votes to Buy Land on Hill". The Washington Post. May 1, 1968. p. B4; "Property Purchase Plan Approved". The Evening Star. May 1, 1968. p. A8.

- ^ "Senate Offices, Art Gallery Annex Bill Advances". The Evening Star. May 23, 1968. p. A23.

- ^ Elder, Shirley (September 27, 1968). "House Trips Up Senate on Office Building Plan". The Evening Star. p. D3; Kaiser, Robert G. (September 27, 1968). "House Spurns Tradition to Reject Senate's Bid to Buy Building Site". The Washington Post. p. A10; "Women Win Their Fight For Land". The Washington Post. September 27, 1968. p. C1.

- ^ "Senate Votes to Acquire Third Office Building Site". The Evening Star. October 9, 1969. p. B4; "Capitol Hill Preservation". The Washington Star-News. July 1, 1974. p. A10.

- ^ Kabaker, Harvey (June 20, 1974). "The Senate Sides With The Gals". The Washington Star-News. p. A21.

- ^ "LBJ Park May Face A Delay". The Washington Star-News. February 18, 1975. p. A9.

- ^ Shultz 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Fogle 2009, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b Evelyn, Dickson & Ackerman 2008, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Eilperin, Juliet (April 12, 2016). "A new memorial to tell 'the story of a century of courageous activism by American women'". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Hirschfeld, Julie (April 12, 2016). "House With Long Activist History Is Now Monument to Equality". The New York Times. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ National Park Service official site: Conditions

- ^ Fogle 2009, p. 39.

- ^ "Where the British Met Resistance in 1812". The Evening Star. October 10, 1942. p. 14.

- ^ "This Week in Washington". The Washington Post. August 26, 1974. p. A4.

- ^ Carol Ann Poh (August 23, 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination: Alva Belmont House / Sewall–Belmont House" (pdf). National Park Service.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) and Accompanying five photos, exterior, from 1961, 1969, and 1975 (32 KB) - ^ "Landmarks". The Evening Star. September 19, 1974. p. C4.

- ^ Niedt, Bob (August 12, 2015). "Capitol Hill women's history site may become Park Service entity". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Shultz 1998, p. 14.

- ^ Ross 1986, p. 75.

- ^ Kaiser 2008, p. 448.

- ^ Moeller & Weeks 2006, p. 40.

- ^ Scott & Lee 1993, p. 251.

- ^ Grooms & Lednum 2005, p. 26.

- ^ Benedetto, Du Vall & Donovan 2001, p. 189.

- ^ a b c Shultz 1998, p. 15.

- ^ Burke & Powers 2016, p. 51.

Bibliography

[edit]- Benedetto, Robert; Du Vall, Kathleen; Donovan, Jane (2001). Historical Dictionary of Washington, D.C.. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810840942.

- Brugger, Robert J. (1996). Maryland, a Middle Temperament, 1634–1980. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801833991.

- Burke, Susan; Powers, Alice L. (2016). DK Eyewitness Washington, D.C. New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 9781465439697.

- Caggiula, Samuel M.; Brackett, Beverley (2008). City in Time: Washington, D.C. New York: Sterling. ISBN 9781402736094.

- Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds (1931). Public Buildings and Grounds. No. 12. 71st Cong., 2d sess. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. hdl:2027/mdp.39015053605583.

- Evelyn, Douglas; Dickson, Paul; Ackerman, S.J. (2008). On This Spot: Pinpointing the Past in Washington, D.C. Sterling, Va.: Capital Books. ISBN 9781933102702.

- Crew, Harvey W.; Webb, William Bensing; Wooldridge, John (1892). Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C. Dayton, Ohio: United Brethren Publishing House.

- Eberlein, Harold Donaldson; Hubbard, Cortlandt Van Dyke (1958). Historic Houses of George-Town & Washington City. Richmond, Va.: The Dietz Press.

- Fogle, Jeanne (2009). A Neighborhood Guide to Washington, D.C.'s Hidden History. Charleston, S.C.: History Press. ISBN 9781596296527.

- Grooms, Thomas B.; Lednum, Taylor J. (2005). The Majesty of Capitol Hill. Gretna, La.: Pelican Publishing Co. ISBN 9781589802285.

- Gournay, Isabelle (2004). "Washington: The DC's History of Unresolved Planning Conflicts". Planning Twentieth-Century Capital Cities (Report). New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415280617.

- Gutheim, Frederick A.; Lee, Antoinette J. (2006). Worthy of the Nation: Washington, D.C., from L'Enfant to the National Capital Planning Commission. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801883286.

- Kaiser, Harvey H. (2008). The National Park Architecture Sourcebook. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 9781568987422.

- McCavitt, John; George, Christopher T. (2016). The Man Who Captured Washington: Major General Robert Ross and the War of 1812. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806155319.

- Moeller, Gerard Martin; Weeks, Christopher (2006). AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington, D.C. (Report). Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801884672.

- Ross, Betty (1986). A Museum Guide to Washington, D.C.. Washington, D.C.: Americana Press. ISBN 9780961614409.

- Scott, Pamela; Lee, Antoinette Josephine (1993). Buildings of the District of Columbia. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195061468.

- Shultz, Scott G. (1998). Sewall–Belmont House (Alva Belmont House) (National Woman's Party Headquarters). Sewall-Belmont House National Historic Site (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service.

External links

[edit]- Belmont–Paul Women's Equality National Monument – National Park Service

- 2016 establishments in Washington, D.C.

- Capitol Hill

- Federal architecture in Washington, D.C.

- Historic house museums in Washington, D.C.

- Houses completed in 1800

- Houses on the National Register of Historic Places in Washington, D.C.

- National Historic Landmarks in Washington, D.C.

- National Historic Sites in Washington, D.C.

- National monuments designated by Barack Obama

- National monuments in Washington, D.C.

- National Park Service national monuments in Washington, D.C.

- Protected areas established in 2016

- Women's museums in the United States

- National Capital Parks-East

- Alice Paul

- Monuments and memorials to women's suffrage in the United States

- National Woman's Party

- Slave cabins and quarters in the United States

- Women in Washington, D.C.