Srebrenica massacre

| Srebrenica massacre Srebrenica genocide | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Bosnian War and the Bosnian genocide | |

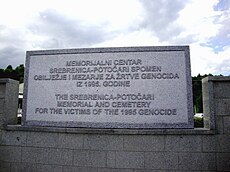

Some of the gravestones for the nearly 7,000 identified victims buried at the Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial and Cemetery for the Victims of the 1995 genocide.[1] | |

| Native name | Genocid u Srebrenici / Геноцид у Сребреници |

| Location | Srebrenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Coordinates | 44°06′N 19°18′E / 44.100°N 19.300°E |

| Date | 11 July 1995 – 31 July 1995 |

| Target | Bosniak men and boys |

Attack type | Genocide, mass murder, ethnic cleansing, genocidal rape, Androcide |

| Deaths | 8,372[2] |

| Perpetrators | |

| Motive | Anti-Bosniak sentiment, Serbian irredentism, Islamophobia, Serbianisation |

The Srebrenica massacre,[a] also known as the Srebrenica genocide,[b][8] was the July 1995 genocidal killing[9] of more than 8,000[10] Bosniak Muslim men and boys in and around the town of Srebrenica during the Bosnian War.[11] It was mainly perpetrated by units of the Bosnian Serb Army of Republika Srpska under Ratko Mladić, though the Serb paramilitary unit Scorpions also participated.[6][12] The massacre was the first legally recognised genocide in Europe since the end of World War II.[13]

Before the massacre, the United Nations (UN) had declared the besieged enclave of Srebrenica a "safe area" under its protection. A UN Protection Force contingent of 370[14] lightly armed Dutch soldiers failed to deter the town's capture and subsequent massacre.[15][16][17][18] A list of people missing or killed during the massacre contains 8,372 names.[2] As of July 2012[update], 6,838 genocide victims had been identified through DNA analysis of body parts recovered from mass graves;[19] as of July 2021[update], 6,671 bodies had been buried at the Memorial Centre of Potočari, while another 236 had been buried elsewhere.[20]

Some Serbs have claimed the massacre was retaliation for civilian casualties inflicted on Bosnian Serbs by Bosniak soldiers from Srebrenica under the command of Naser Orić.[21][22] These 'revenge' claims have been rejected and condemned by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the UN as bad faith attempts to justify the genocide.

In 2004, in a unanimous ruling on the case of Prosecutor v. Krstić, the Appeals Chamber of the ICTY ruled the massacre of the enclave's male inhabitants constituted genocide, a crime under international law.[23] The ruling was also upheld by the International Court of Justice in 2007.[24] The forcible transfer and abuse of between 25,000 and 30,000 Bosniak Muslim women, children and elderly which accompanied the massacre, was found to constitute genocide, when accompanied with the killings and separation of the men.[25][26] In 2002, following a report on the massacre, the government of the Netherlands resigned, citing its inability to prevent the massacre. In 2013, 2014 and 2019, the Dutch state was found liable by its supreme court and the Hague district court, of failing to prevent more than 300 deaths.[27][28][29][30] In 2013, Serbian president Tomislav Nikolić apologised for "the crime" of Srebrenica but refused to call it genocide.[31]

In 2005, then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan described the massacre as "a terrible crime – the worst on European soil since the Second World War",[32] and in May 2024, the UN designated July 11 as the annual International Day of Reflection and Commemoration of the 1995 Genocide in Srebrenica.[33][34]

Background

[edit]Conflict in Eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina

[edit]The multiethnic Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was mainly inhabited by Muslim Bosniaks (44%), Orthodox Serbs (31%) and Catholic Croats (17%). As the former Yugoslavia began to disintegrate, the region declared national sovereignty in 1991 and held a referendum for independence in February 1992. The result, which favoured independence, was opposed by Bosnian Serb political representatives, who boycotted the referendum. The Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was formally recognised by the European Community in April 1992 and the UN in May 1992.[35][36]

Following the declaration of independence, Bosnian Serb forces, supported by the Serbian government of Slobodan Milošević and the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), attacked Bosnia and Herzegovina, to secure and unify the territory under Serb control, and create an ethnically homogenous Serb state of Republika Srpska.[37] In the struggle for territorial control, the non-Serb populations from areas under Serbian control, especially the Bosniak population in East Bosnia, near the Serbian borders, were subject to ethnic cleansing.[38]

Ethnic cleansing

[edit]Srebrenica, and the surrounding Central Podrinje region, had immense strategic importance to the Bosnian Serb leadership. It was the bridge to disconnected parts of the envisioned ethnic state of Republika Srpska.[39] Capturing Srebrenica and eliminating its Muslim population would also undermine the viability of the Bosnian Muslim state.[39]

In 1991, 73% of the population in Srebrenica were Bosnian Muslims and 25% Bosnian Serbs.[40] Tension between Muslims and Serbs intensified in the early 1990s, as the local Serb population were provided with weapons and military equipment distributed by Serb paramilitary groups, the Yugoslav People's Army (the "JNA") and the Serb Democratic Party (the "SDS").[40]: 35

By April 1992, Srebrenica had become isolated by Serb forces. On 17 April, the Bosnian Muslim population was given a 24-hour ultimatum to surrender all weapons and leave town. Srebrenica was briefly captured by the Bosnian Serbs and retaken by Bosnian Muslims on 8 May 1992. Nonetheless, the Bosnian Muslims remained surrounded by Serb forces, and cut off from outlying areas. The Naser Orić trial judgment described the situation:[40]: 47

Between April 1992 and March 1993 ... Srebrenica and the villages in the area held by Bosniak were constantly subjected to Serb military assaults, including artillery attacks, sniper fire ... occasional bombing from aircraft. Each onslaught followed a similar pattern. Serb soldiers and paramilitaries surrounded a Bosnian Muslim village ... called upon the population to surrender their weapons, and then began with indiscriminate shelling and shooting ... they then entered the village ... expelled or killed the population, who offered no significant resistance, and destroyed their homes ... Srebrenica was subjected to indiscriminate shelling from all directions daily. Potočari, in particular, was a daily target ... because it was a sensitive point in the defence line around Srebrenica. Other Bosnian Muslim settlements were routinely attacked as well. All this resulted in a great number of refugees and casualties.

Between April and June 1992 Bosnian Serb forces, with support from the JNA, destroyed 296 predominantly Bosniak villages around Srebrenica, forcibly uprooted 70,000 Bosniaks from their homes and systematically massacred at least 3,166 Bosniaks, including women, children and elderly.[41] In neighbouring Bratunac, Bosniaks were either killed or forced to flee to Srebrenica, resulting in 1,156 deaths.[42] Thousands of Bosniaks were killed in Foča, Zvornik, Cerska and Snagovo.[43]

1992–93: Struggle for Srebrenica

[edit]Over the remainder of 1992, offensives by Bosnian government forces from Srebrenica increased the area under their control, and by January 1993 they had linked with Bosniak-held Žepa to the south and Cerska to the west. The Srebrenica enclave had reached its peak size of 900 square kilometres (350 square miles), though it was never linked to the main area of Bosnian-government controlled land in the west and remained "a vulnerable island amid Serb-controlled territory".[44] Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) forces under Naser Orić used Srebrenica as a staging ground to attack neighboring Serb villages inflicting many casualties.[45][46] In 1993, the militarized Serb village of Kravica was attacked by ARBiH, which resulted in Serb civilian casualties. The resistance to the Serb siege of Srebrenica by the ARBiH, under Orić was seen as a catalyst for the massacre.

Serbs started persecuting Bosniaks in 1992. Serbian propaganda deemed Bosniak resistance to Serb attacks as a ground for revenge. According to French General Philippe Morillon, Commander of the UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR), in testimony at the ICTY in 2004:

JUDGE ROBINSON: Are you saying, then, General, that what happened in 1995 was a direct reaction to what Naser Oric did to the Serbs two years before?

THE WITNESS: [Interpretation] Yes. Yes, Your Honour. I am convinced of that. This doesn't mean to pardon or diminish the responsibility of the people who committed that crime, but I am convinced of that, yes.[47]

Over the next few months, the Serb military captured the villages of Konjević Polje and Cerska, severing the link between Srebrenica and Žepa, and reducing the Srebrenica enclave to 150 square kilometres. Bosniak residents of the outlying areas converged on Srebrenica and its population swelled to between 50,000 and 60,000, about ten times the pre-war population.[48] General Morillon visited Srebrenica in March 1993. The town was overcrowded and siege conditions prevailed. There was almost no running water as the advancing Serb forces had destroyed water supplies; people relied on makeshift generators for electricity. Food, medicine and other essentials were scarce. The conditions rendered Srebrenica a slow death camp.[48] Morillon told panicked residents at a public gathering that the town was under the protection of the UN, and he would never abandon them. During March and April 1993 several thousand Bosniaks were evacuated, under the auspices of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The evacuations were opposed by the Bosnian government in Sarajevo, as contributing to the ethnic cleansing of predominantly Bosniak territory.

The Serb authorities remained intent on capturing the enclave. On 13 April 1993, the Serbs told the UNHCR representatives that they would attack the town within 2 days unless the Bosniaks surrendered and agreed to be evacuated.[49]

Starvation

[edit]With the failure to demilitarize and the shortage of supplies getting in, Orić consolidated his power and controlled the black market. Orić's men began hoarding food, fuel, cigarettes and embezzled money sent by aid agencies to support Muslim orphans.[50] Basic necessities were out of reach for many in Srebrenica due to Orić's actions. UN officials were beginning to lose patience with the ARBiH in Srebrenica and saw them as "criminal gang leaders, pimps and black marketeers".[51]

A former Serb soldier of the "Red Berets" unit described the tactics used to starve and kill the besieged population:

It was almost like a game, a cat-and-mouse hunt. But of course, we greatly outnumbered the Muslims, so in almost all cases, we were the hunters and they were the prey. We needed them to surrender, but how do you get someone to surrender in a war like this? You starve them to death. So very quickly we realised that it wasn't really weapons being smuggled into Srebrenica that we should worry about, but food. They were truly starving in there, so they would send people out to steal cattle or gather crops, and our job was to find and kill them ... No prisoners. Well, yes, if we thought they had useful information, we might keep them alive until we got it out of them, but in the end, no prisoners ... The local people became quite indignant, so sometimes we would keep someone alive to hand over to them [to kill] just to keep them happy.[52]

When British journalist Tony Birtley visited Srebrenica in March 1993, he took footage of civilians starving to death.[53] The Hague Tribunal in the case of Orić concluded:

Bosnian Serb forces controlling the access roads were not allowing international humanitarian aid—most importantly, food and medicine—to reach Srebrenica. As a consequence, there was a constant and serious shortage of food causing starvation to peak in the winter of 1992/1993. Numerous people died or were in an extremely emaciated state due to malnutrition. Bosnian Muslim fighters and their families, however, were provided with food rations from existing storage facilities. The most disadvantaged group among the Bosnian Muslims was that of the refugees, who usually lived on the streets and without shelter, in freezing temperatures. Only in November and December 1992, did two UN convoys with humanitarian aid reach the enclave, and this despite Bosnian Serb obstruction.[54]

1993-1995: Srebrenica "safe area"

[edit]UN Security Council declares Srebrenica a "safe area"

[edit]

On 16 April 1993, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 819, which demanded "all parties ... treat Srebrenica and its surroundings as a safe area which should be free from any armed attack or ... hostile act".[55] On 18 April, the first group of UNPROFOR troops arrived in Srebrenica. UNPROFOR deployed Canadian troops to protect it as one of five newly established UN "safe areas".[48] UNPROFOR's presence prevented an all-out assault, though skirmishes and mortar attacks continued.[48]

On 8 May 1993 agreement was reached for demilitarization of Srebrenica. According to a UN report, "General [Sefer] Halilović and General Mladić agreed on measures covering the whole of the Srebrenica enclave and ... Žepa. ... Bosniac forces ... would hand over their weapons, ammunition and mines to UNPROFOR, after which Serb 'heavy weapons and units that constitute a menace to the demilitarised zones ... will be withdrawn.' Unlike the earlier agreement, it stated specifically that Srebrenica was to be considered a 'demilitarised zone', as referred to in the ... Geneva Conventions."[56] Both parties violated the agreement, though two-years of relative stability followed the establishment of the enclave.[57] Lieutenant colonel Thom Karremans (the Dutchbat Commander) testified that his personnel were prevented from returning to the enclave by Serb forces, and that equipment and ammunition were prevented from getting in.[58] Bosniaks in Srebrenica complained of attacks by Serb soldiers, while to the Serbs it appeared Bosnian forces were using the "safe area", as a convenient base to launch counter-offensives and UNPROFOR was failing to prevent it.[58]: 24 General Sefer Halilović admitted ARBiH helicopters had flown in violation of the no-fly zone and he had dispatched 8 helicopters with ammunition for the 28th Division.[58]: 24

Between 1,000 and 2,000 soldiers from the VRS Drina Corps Brigades were deployed around the enclave, equipped with tanks, armoured vehicles, artillery and mortars. The 28th Mountain Division of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) in the enclave was neither well organised nor equipped, and lacked a firm command structure and communications system. Some of its soldiers carried old hunting rifles or no weapons, few had proper uniforms.

UN failure to demilitarise

[edit]A Security Council mission led by Diego Arria arrived on 25 April 1993 and, in their report to the UN, condemned the Serbs for perpetrating "a slow-motion process of genocide".[59] The mission stated "Serb forces must withdraw to points from which they cannot attack, harass or terrorise the town. UNPROFOR should be in a position to determine the related parameters. The mission believes, as does UNPROFOR, that the actual 4.5 km (3 mi) by 0.5 km (530 yd) decided as a safe area should be greatly expanded." Specific instructions from UN Headquarters in New York stated UNPROFOR should not be too zealous in searching for Bosniak weapons and the Serbs should withdraw their heavy weapons before the Bosniaks disarmed, which the Serbs never did.[59]

Attempts to demilitarise the ARBiH and force withdrawal of the VRS proved futile. The ARBiH hid most of their heavy weapons, modern equipment and ammunition in the surrounding forest and only handed over disused and old weaponry.[60] The VRS refused to withdraw from the front lines due to intelligence they received regarding ARBiH's hidden weaponry.[60]

In March 1994, UNPROFOR sent 600 Dutch soldiers ("Dutchbat") to replace the Canadians. By March 1995, Serb forces controlled all territory surrounding Srebrenica, preventing even UN access to the supply road. Humanitarian aid decreased and living conditions quickly deteriorated.[48] UNPROFOR presence prevented all-out assault on the safe area, though skirmishes and mortar attacks continued.[48] The Dutchbat alerted UNPROFOR command to the dire conditions, but UNPROFOR declined to send humanitarian relief or military support.[48]

Organisation of UNPROFOR and UNPF

[edit]In April 1995, UNPROFOR became the name used for the Bosnia and Herzegovina regional command of the now-renamed United Nations Peace Forces (UNPF).[61] The 2002 report Srebrenica: a 'safe' area notes "On 12 June 1995 a new command was created under UNPF",[61] with "12,500 British, French and Dutch troops equipped with tanks and high calibre artillery to increase the effectiveness and the credibility of the peacekeeping operation".[61] The report states:

In the UNPROFOR chain of command, Dutchbat occupied the fourth tier, with the sector commanders occupying the third tier. The fourth tier primarily had an operational task ... Dutchbat was expected to operate as an independent unit with its own logistic arrangements. Dutchbat was dependent on the UNPROFOR organization to some extent for crucial supplies such as fuel. For the rest, it was expected to obtain its supplies from the Netherlands. From an organizational point of view, the battalion had two lifelines: UNPROFOR and the Royal Netherlands Army. Dutchbat had been assigned responsibility for the Srebrenica Safe Area. Neither UNPROFOR nor Bosnia-Hercegovina paid much attention to Srebrenica, however. Srebrenica was situated in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, which was geographically and mentally far removed from Sarajevo and Zagreb. The rest of the world was focused on the fight for Sarajevo ... As a Safe Area, Srebrenica only occasionally managed to attract the attention of the world press or the UN Security Council. That is why the Dutch troops there remained of secondary importance, in operational and logistic terms, for so long; and why the importance of the enclave in the battle for domination between the Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Muslims failed to be recognised for so long.[62]

The situation deteriorates

[edit]By early 1995, fewer and fewer supply convoys were making it through to the enclave. The situation in Srebrenica and other enclaves had deteriorated into lawless violence as prostitution among young Muslim girls, theft and black marketeering proliferated.[63] Already meager resources dwindled further, and even the UN forces started running dangerously low on food, medicine, ammunition and fuel, eventually being forced to start patrolling on foot. Dutch soldiers who left on leave were not allowed to return,[59] and their number dropped from 600 to 400 men. In March and April, the Dutch soldiers noticed a build-up of Serb forces.

In March 1995, Radovan Karadžić, President of the Republika Srpska (RS), despite pressure from the international community to end the war and efforts to negotiate peace, issued a directive to the VRS concerning long-term strategy in the enclave. The directive, known as "Directive 7", specified the VRS was to:

Complete the physical separation of Srebrenica from Žepa as soon as possible, preventing even communication between individuals in the two enclaves. By planned and well-thought-out combat operations, create an unbearable situation of total insecurity with no hope of further survival or life for the inhabitants of Srebrenica.[64]

By mid-1995, the humanitarian situation in the enclave was catastrophic. In May, following orders, Orić and his staff left the enclave, leaving senior officers in command of the 28th Division. In late June and early July, the 28th Division issued reports including urgent pleas for the humanitarian corridor to be reopened. When this failed, Bosniak civilians began dying from starvation. On 7 July the mayor reported 8 residents had died.[65] On 4 June, UNPROFOR commander Bernard Janvier, a Frenchman, secretly met with Mladić to obtain the release of hostages, many of whom were French. Mladić demanded of Janvier that there would be no more airstrikes.[66]

In the weeks leading up to the assault on Srebrenica by the VRS, ARBiH forces were ordered to carry out diversion and disruption attacks on the VRS by the high command.[67] On one occasion on 25 June, ARBiH forces attacked VRS units on the Sarajevo–Zvornik road, inflicting high casualties and looting VRS stockpiles.[67]

6–11 July 1995: Serb takeover

[edit]The Serb offensive against Srebrenica began in earnest on 6 July. The VRS, with 2,000 soldiers, were outnumbered by the defenders and did not expect the assault to be an easy victory.[67] 5 UNPROFOR observation posts in the south of the enclave fell in the face of the Bosnian Serb advance. Some Dutch soldiers retreated into the enclave after their posts were attacked, the crews of the other observation posts surrendered into Serb custody. The defending Bosnian forces numbering 6,000 came under fire and were pushed back towards the town. Once the southern perimeter began to collapse, about 4,000 Bosniak residents, who had been living in a Swedish housing complex for refugees nearby, fled north into Srebrenica. Dutch soldiers reported the advancing Serbs were "cleansing" the houses in the south of the enclave.[68]

On 8 July, a Dutch YPR-765 armoured vehicle took fire from the Serbs and withdrew. A group of Bosniaks demanded the vehicle stay to defend them, and established a makeshift barricade to prevent its retreat. As the vehicle withdrew, a Bosniak farmer manning the barricade threw a grenade onto it and killed Dutch soldier Raviv van Renssen.[69] On 9 July, emboldened by success, little resistance from the demilitarised Bosniaks and lack of reaction from the international community, President Karadžić issued a new order authorising the 1,500-strong[70] VRS Drina Corps to capture Srebrenica.[68]

The following morning, 10 July, Lieutenant Colonel Karremans made urgent requests for air support from NATO to defend Srebrenica as crowds filled the streets, some of whom carried weapons. VRS tanks were approaching, and NATO airstrikes on these began on 11 July. NATO bombers attempted to attack VRS artillery locations outside the town, but poor visibility forced NATO to cancel this. Further air attacks were cancelled after VRS threats to bomb the UN's Potočari compound, kill Dutch and French military hostages and attack surrounding locations where 20,000 to 30,000 civilian refugees were situated.[68] 30 Dutchbat were taken hostage by Mladic's troops.[48]

Late in the afternoon of 11 July, General Mladić, accompanied by General Živanović (Commander of the Drina Corps), General Krstić (Deputy Commander of the Drina Corps) and other VRS officers, took a triumphant walk through the deserted streets of Srebrenica.[68] In the evening,[71] Lieutenant Colonel Karremans was filmed drinking a toast with Mladić during the bungled negotiations on the fate of the civilian population grouped in Potočari.[14][72]

Massacre

[edit]The two highest-ranking Serb politicians from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Karadžić and Momčilo Krajišnik, both indicted for genocide, were warned by VRS commander Mladić (found guilty of genocide in 2017) that their plans could not be realized without committing genocide. Mladić said at a parliamentary session of 12 May 1992:

People are not little stones or keys in someone's pocket, that can be moved from one place to another just like that. ... Therefore, we cannot precisely arrange for only Serbs to stay in one part of the country while removing others painlessly. I do not know how Mr. Krajišnik and Mr. Karadžić will explain that to the world. That is genocide.[73]

Increasing concentration of refugees in Potočari

[edit]

By the evening of 11 July, approximately 20,000–25,000 Bosniak refugees from Srebrenica were gathered in Potočari, seeking protection within the UNPROFOR Dutchbat headquarters. Several thousand had pressed inside the compound, while the rest were spread throughout neighbouring factories and fields. Though most were women, children, elderly or disabled, 63 witnesses estimated there were at least 300 men inside the compound and between 600–900 in the crowd outside.[74]

Conditions included "little food or water" and sweltering heat. A UNPROFOR Dutchbat officer described the scene:

They were panicked, they were scared, and they were pressing each other against the soldiers, my soldiers, the UN soldiers that tried to calm them. People who fell were trampled on. It was a chaotic situation.[74]

On 12 July, the UN Security Council, in Resolution 1004, expressed concern at the humanitarian situation in Potočari, condemned the offensive by Bosnian Serb forces and demanded immediate withdrawal. On 13 July, the Dutch forces expelled 5 Bosniak refugees from the compound despite knowing men outside were being killed.[75]

Crimes committed in Potočari

[edit]On 12 July the refugees in the compound could see VRS members setting houses and haystacks on fire. Throughout the afternoon, Serb soldiers mingled in the crowd and summary executions of men occurred.[74] In the morning of 12 July, a witness saw a pile of 20-30 bodies heaped up behind the Transport Building, alongside a tractor-like machine. Another testified he saw a soldier slay a child with a knife, in the middle of a crowd of expellees. He said he saw Serb soldiers execute more than a hundred Bosniak Muslim men behind the Zinc Factory, then load their bodies onto a truck, though the number and nature of the murders contrasted with other evidence in the Trial Record, which indicated killings in Potočari were sporadic in nature. Soldiers were picking people out of the crowd and taking them away. A witness recounted how three brothers – one merely a child, the others in their teens – were taken out in the night. When the boys' mother went looking for them, she found them stark naked and with their throats slit.[74][76]

That night, a Dutchbat medical orderly witnessed two Serb soldiers raping a woman.[76] A survivor, Zarfa Turković, described the horrors: "Two [Serb soldiers] took her legs and raised them in the air, while the third began raping her. Four of them were taking turns on her. People were silent, and no one moved. She was screaming and yelling and begging them to stop. They put a rag into her mouth, and then we just heard silent sobs."[77][78]

Murder of Bosniak men and boys in Potočari

[edit]From the morning of 12 July, Serb forces began gathering men and boys from the refugee population in Potočari and holding them in separate locations, and as the refugees began boarding the buses headed north towards Bosniak-held territory, Serb soldiers separated men of military age who were trying to clamber aboard. Occasionally, younger and older men were stopped as well (some as young as 14).[79][80][81] These men were taken to a building referred to as the "White House". By the evening of 12 July, Major Franken of Dutchbat heard that no men were arriving with the women and children, at their destination in Kladanj.[74] The UNHCR Director of Operations, Peter Walsh, was dispatched to Srebrenica by Chief of Mission, Damaso Feci, to evaluate what emergency aid could be provided rapidly. Walsh and his team arrived at Gostilj, just outside Srebrenica, in the afternoon only to be turned away by VRS forces. Despite claiming freedom of movement rights, the UNHCR team was not allowed to proceed and forced to head back north to Bijelina. Throughout, Walsh relayed reports back to UNHCR in Zagreb about the unfolding situation, including witnessing the enforced movement and abuse of Muslim men and boys, and the sound of executions taking place.[citation needed]

On 13 July, Dutchbat troops witnessed definite signs Serb soldiers were murdering Bosniak men who had been separated. Corporal Vaasen saw two soldiers take a man behind the "White House", heard a shot and saw the two soldiers reappear alone. Another Dutchbat officer saw Serb soldiers murder an unarmed man with a gunshot to the head, and heard gunshots 20–40 times an hour throughout the afternoon. When the Dutchbat soldiers told Colonel Joseph Kingori, a United Nations Military Observer (UNMO) in the Srebrenica area, that men were being taken behind the "White House" and not coming back, Kingori went to investigate. He heard gunshots as he approached, but was stopped by Serb soldiers before he could find out what was going on.[74]

Some executions were carried out at night under arc lights, and bulldozers then pushed the bodies into mass graves.[82] According to evidence collected from Bosniaks by French policeman Jean-René Ruez, some were buried alive; he heard testimony describing Serb forces killing and torturing refugees, streets littered with corpses, people committing suicide to avoid having their noses, lips and ears chopped off, and adults being forced to watch soldiers kill their children.[82]

Rape and abuse of civilians

[edit]Thousands of women and girls suffered rape and sexual abuse and other forms of torture. According to the testimony of Zumra Šehomerovic:

The Serbs began at a certain point to take girls and young women out of the group of refugees. They were raped. The rapes often took place under the eyes of others and sometimes even under the eyes of the children of the mother. A Dutch soldier stood by and he simply looked around with a Walkman on his head. He did not react at all to what was happening. It did not happen just before my eyes, for I saw that personally, but also before the eyes of us all. The Dutch soldiers walked around everywhere. It is impossible that they did not see it.

There was a woman with a small baby a few months old. A Chetnik told the mother that the child must stop crying. When the child did not stop crying, he snatched the child away and cut its throat. Then he laughed. There was a Dutch soldier there who was watching. He did not react at all.

I saw yet more frightful things. For example, there was a girl, who must have been about nine years old. At a certain moment, some Chetniks recommended to her brother that he rape the girl. He did not do it and I also think that he could not have done it for he was still just a child. Then they murdered that young boy. I have personally seen all that. I really want to emphasize that all this happened in the immediate vicinity of the base. In the same way, I also saw other people who were murdered. Some of them had their throats cut. Others were beheaded.[83]

Testimony of Ramiza Gurdić:

I saw how a young boy of about ten was killed by Serbs in Dutch uniform. This happened in front of my own eyes. The mother sat on the ground and her young son sat beside her. The young boy was placed on his mother's lap. The young boy was killed. His head was cut off. The body remained on the lap of the mother. The Serbian soldier placed the head of the young boy on his knife and showed it to everyone. ... I saw how a pregnant woman was slaughtered. There were Serbs who stabbed her in the stomach, cut her open and took two small children out of her stomach and then beat them to death on the ground. I saw this with my own eyes.[84]

Testimony of Kada Hotić:

There was a young woman with a baby on the way to the bus. The baby cried and a Serbian soldier told her that she had to make sure that the baby was quiet. Then the soldier took the child from the mother and cut its throat. I do not know whether Dutchbat soldiers saw that. ... There was a sort of fence on the left-hand side of the road to Potocari. I heard then a young woman screaming very close by (4 or 5 meters away). I then heard another woman beg: "Leave her, she is only nine years old." The screaming suddenly stopped. I was so in shock that I could scarcely move. ... The rumour later quickly circulated that a nine-year-old girl had been raped.[85]

That night, a Dutchbat medical orderly came across two Serb soldiers raping a young woman:

[W]e saw two Serb soldiers, one of them was standing guard and the other one was lying on the girl, with his pants off. And we saw a girl lying on the ground, on some kind of mattress. There was blood on the mattress, even she was covered with blood. She had bruises on her legs. There was even blood coming down her legs. She was in total shock. She went totally crazy.

Bosnian Muslim refugees nearby could see the rape, but could do nothing about it because of Serb soldiers standing nearby. Other people heard women screaming, or saw women being dragged away. Several individuals were so terrified that they committed suicide by hanging themselves. Throughout the night and early the next morning, stories about the rapes and killings spread through the crowd and the terror in the camp escalated.

Screams, gunshots and other frightening noises were audible throughout the night and no one could sleep. Soldiers were picking people out of the crowd and taking them away: some returned; others did not.[86]

Deportation of women

[edit]As a result of exhaustive UN negotiations with Serb troops, around 25,000 Srebrenica women were forcibly transferred to Bosniak-controlled territory. Some buses apparently never reached safety. According to a witness account by Kadir Habibović, who hid himself on one of the first buses from the base in Potočari to Kladanj, he saw at least one vehicle full of Bosniak women being driven away from Bosnian government-held territory.[87]

Column of Bosniak men

[edit]

On the evening of 11 July, word spread that able-bodied men should take to the woods, form a column with the ARBiH's 28th Division and attempt a breakthrough towards Bosnian government-held territory in the north.[88] They believed they stood a better chance of surviving by trying to escape, than if they fell into Serb hands.[89] Around 10 pm on 11 July the Division command, with the municipal authorities, took the decision to form a column and attempt to reach government territory around Tuzla.[90] Dehydration, along with lack of sleep and exhaustion were further problems; there was little cohesion or common purpose.[91] Along the way, the column was shelled and ambushed. In severe mental distress, some refugees killed themselves. Others were induced to surrender. Survivors claimed they were attacked with a chemical agent that caused hallucinations, disorientation and strange behaviour.[92][93][94][95] Infiltrators in civilian clothing confused, attacked and killed refugees.[92][96] Many taken prisoner were killed on the spot.[92] Others were collected and taken to remote locations, for execution.

The attacks broke the column into smaller segments. Only about one third succeeded in crossing the asphalt road between Konjević Polje and Nova Kasaba. This group reached Bosnian government territory on and after 16 July. A second, smaller group (700–800) attempted to escape into Serbia via Mount Kvarac, Bratunac, or across the river Drina and via Bajina Bašta. It is not known how many were intercepted and killed. A third group headed for Žepa, estimates of how many vary between 300 to 850. Pockets of resistance apparently remained behind and engaged Serb forces.[citation needed]

Tuzla column departs

[edit]Almost all the 28th Division, 5,500 to 6,000 soldiers, not all armed, gathered in Šušnjari, in the hills north of Srebrenica, along with about 7,000 civilians. They included a few women.[90] Others assembled in the nearby village of Jaglići.[97]

Around midnight, the column started moving along the axis between Konjević Polje and Bratunac. It was preceded by four scouts, 5 km ahead.[98] Members walked one behind the other, following the paper trail laid by a demining unit.[99]

The column was led by 50–100 of the best soldiers from each brigade, carrying the best equipment. Elements of the 284th Brigade were followed by the 280th Brigade. Civilians accompanied by other soldiers followed, and at the back was the independent battalion.[90] The command and armed men were at the front, following the deminer unit.[99] Others included political leaders of the enclave, medical staff and families of prominent Srebrenicans. A few women, children and elderly travelled with the column in the woods.[88][100] The column was 12-15km long, two and a half hours separating head from tail.[90]

The attempt to reach Tuzla surprised the VRS and caused confusion, as the VRS had expected the men to go to Potočari. Serb general Milan Gvero, in a briefing, referred to the column as "hardened and violent criminals who will stop at nothing to prevent being taken prisoner".[101] The Drina The VRS Main Staff ordered all available manpower to find any Muslim groups observed, prevent them crossing into Muslim territory, take them prisoner and hold them in buildings that could be secured by small forces.[102]

Ambush at Kamenica Hill

[edit]During the night, poor visibility, fear of mines and panic induced by artillery fire split the column in two.[103] On the afternoon of 12 July, the front section emerged from the woods and crossed the asphalt road from Konjević Polje and Nova Kasaba. Around 6pm, the VRS Army located the main part of the column around Kamenica. Around 8pm this part, led by the municipal authorities and wounded, started descending Kamenica Hill towards the road. After about 40 men had crossed, soldiers of the VRS arrived from the direction of Kravica in trucks and armoured vehicles, including a white vehicle with UNPROFOR symbols, calling over the loudspeaker, to surrender.[103]

Yellow smoke was observed, followed by strange behaviour, including suicides, hallucinations and column members attacking one another.[92] Survivors claimed they were attacked with a chemical agent that caused hallucinations and disorientation.[93][94] General Tolimir was an advocate of the use of chemical weapons against the ArBiH.[95][104] Shooting and shelling began, which continued into the night. Armed members of the column returned fire and all scattered. Survivors at least 1,000 engaged at close range by small arms. Hundreds appear to have been killed as they fled the open area and some were said to have killed themselves to escape capture.[citation needed]

VRS and Ministry of Interior personnel persuaded column members to surrender, by promising them safe transportation towards Tuzla, under UNPROFOR and Red Cross supervision. Appropriated UN and Red Cross equipment was used to deceive them. Belongings were confiscated and some executed on the spot.[103]

The rear of the column lost contact and panic broke out. Many remained in the Kamenica Hill area for days, with the escape route blocked by Serb forces. Thousands of Bosniaks surrendered or were captured. Some were ordered to summon friends and family from the woods. There were reports of Serb forces using megaphones to call on the marchers to surrender, telling them they would be exchanged for Serb soldiers. It was at Kamenica that VRS personnel in civilian dress were reported to have infiltrated the column. Men who survived, described it as a manhunt.[88]

Sandići massacre

[edit]

Close to Sandići, on the main road from Bratunac to Konjević Polje, a witness described the Serbs forcing a Bosniak man to call other Bosniaks down from the mountains. 200–300 men, including the witness' brother, descended to meet the VRS, presumably expecting an exchange of prisoners. The witness hid behind a tree and watched as the men were lined up in seven ranks, each 40 m long, with hands behind their heads; they were then mowed down by machine guns.[92]

Some women, children and elderly people who had been part of the column, were allowed to join buses evacuating women and children from Potočari.[105]

Trek to Mount Udrč

[edit]The central section of the column managed to escape the shooting, reached Kamenica around 11am and waited for the wounded. Captain Golić and the Independent Battalion turned back towards Hajdučko Groblje, to help the casualties. Survivors from the rear, crossed the asphalt roads to the north or the west, and joined the central section. The front third of the column, which had left Kamenica Hill by the time the ambush occurred, headed for Mount Udrč (44°16′59″N 19°3′6″E / 44.28306°N 19.05167°E); crossing the main asphalt road. They reached the base of the mountain on Thursday 13 July and regrouped. At first, it was decided to send 300 ARBiH soldiers back to break through the blockades. When reports came that the central section had crossed the road at Konjević Polje, this plan was abandoned. Approximately 1,000 additional men managed to reach Udrč that night.[106]

Snagovo ambush

[edit]From Udrč, the marchers moved toward the River Drinjača and Mount Velja Glava. Finding Serbs at Mount Velja Glava, on Friday, 14 July, the column skirted the mountain and waited on its slopes, before moving toward Liplje and Marčići. Arriving at Marčići in the evening of 14 July, they were ambushed again near Snagovo by forces equipped with anti-aircraft guns, artillery, and tanks.[107] The column broke through and captured a VRS officer, providing them with a bargaining counter. This prompted an attempt at negotiating a ceasefire, but this failed.[91]

Approaching the frontline

[edit]The evening of 15 July saw the first radio contact between the 2nd Corps and the 28th Division. The Šabić brothers were able to identify each other as they stood on either side of the VRS lines. Early in the morning, the column crossed the road linking Zvornik with Caparde and headed towards Planinci, leaving 100-200 armed marchers behind to wait for stragglers.[citation needed] The column reached Križevići later that day, and remained while an attempt was made to negotiate with Serb forces, for safe passage. They were advised to stay where they were, and allow Serb forces to arrange safe passage. It became apparent, that the small Serb force was only trying to gain time to organise another attack. In the area of Marčići – Crni Vrh, VRS armed forces deployed 500 soldiers and policemen to stop the split part of the column, about 2,500 people, which was moving from Glodi towards Marčići.[citation needed] The column's leaders decided to form small groups of 100–200 and send these to reconnoitre ahead. The 2nd Corps and 28th Division of the ARBiH met each other in Potočani.

Breakthrough at Baljkovica

[edit]The hillside at Baljkovica (44°27′N 18°58′E / 44.450°N 18.967°E) formed the last VRS line separating the column from Bosnian-held territory. The VRS cordon consisted of two lines, the first of which presented a front on the Tuzla side, against the 2nd Corps and the other a front against the approaching 28th Division.[citation needed]

On the evening of 15 July a hailstorm caused Serb forces to take cover. The column's advance group took advantage to attack the Serb rear lines at Baljkovica. The main body of what remained of the column began to move from Krizevici. It reached the area of fighting around 3 am on Sunday, 16 July.[citation needed] At approximately 5am, the 2nd Corps made its first attempt to break through the VRS cordon. The objective was to breakthrough close to the hamlets of Parlog and Resnik. They were joined by Orić and some of his men.[citation needed] Around 8 am, parts of the 28th Division, with the 2nd Corps of the RBiH Army from Tuzla providing artillery support, attacked and breached VRS lines. There was fierce fighting across Baljkovica.[108] The column finally succeeded in breaking through to Bosnian government-controlled territory, between 1-2 pm.[citation needed]

Baljkovica corridor

[edit]Following radio negotiations between the 2nd Corps and Zvornik Brigade, Brigade Command agreed to open a corridor to allow "evacuation" of the column in return for the release of captured policemen and soldiers. The corridor was open 2-5pm.[109] After the corridor was closed between 5 and 6 pm, the Zvornik Brigade Command reported that around 5000 civilians, with probably "a certain number of soldiers" with them had been let through, but "all those who passed were unarmed".[110]

By about 4 August, the ArBiH determined that 3,175 members of the 28th Division had managed to get through to Tuzla. 2,628 members of the Division, soldiers and officers, were considered certain to have been killed. Column members killed was between 8,300 and 9,722.[111]

After closure of the corridor

[edit]Once the corridor had closed, Serb forces recommenced hunting down parts of the column. Around 2,000 refugees were reported to be hiding in the woods in the area of Pobuđe.[110] On 17 July, four children aged between 8 and 14 captured by the Bratunac Brigade were taken to the military barracks in Bratunac.[110][112] Brigade Commander Blagojević suggested the Drina Corps' press unit record this testimony on video.[112]

On 18 July, after a soldier was killed "trying to capture some persons during the search operation", the Zvornik Brigade Command issued an order to execute prisoners, to avoid any risks associated with their capture. The order was presumed to have remained effective until countermanded on 21 July.[110]

Impact on survivors

[edit]According to a 1998 qualitative study involving survivors, many column members exhibited symptoms of hallucinations to varying degrees.[113] Several times, Bosniak men attacked one another, in fear the other was a Serb soldier. Survivors reported seeing people speaking incoherently, running towards VRS lines in a rage and committing suicide using firearms and hand grenades. Although there was no evidence to suggest what exactly caused the behaviour, the study suggested fatigue and stress may have induced this.[113]

A plan to execute the men

[edit]Although Serb forces had long been blamed for the massacre, it was not until 2004—following the Srebrenica Commission's report—that Serb officials acknowledged their forces carried out the mass killing. Their report acknowledged the mass murder of the men and boys was planned, and more than 7,800 were killed.[114][115][116]

A concerted effort was made to capture all Bosniak men of military age.[117] In fact, those captured included many boys well below that age, and men years above that age, who remained in the enclave following the take-over of Srebrenica. These men and boys were targeted, regardless of whether they chose to flee to Potočari or join the column. The operation to capture and detain the men was well-organised and comprehensive. The buses which transported women and children, were systematically searched for men.[117]

Mass executions

[edit]The amount of planning and high-level coordination invested in killing thousands in a few days, is apparent from the scale and methodical nature in which the executions were carried out.[citation needed]

The Army of Republika Srpska took the largest number of prisoners on 13 July, along the Bratunac-Konjević Polje road. Witnesses describe the assembly points, such as the field at Sandići, agricultural warehouses in Kravica, the school in Konjević Polje, the football pitch in Nova Kasaba, Lolići and Luke school. Several thousand people were herded in the field near Sandići and on the Nova Kasaba pitch, where they were searched and put into smaller groups. In a video by journalist Zoran Petrović, a Serb soldier states that at least 3,000–4,000 men gave themselves up on the road. By the late afternoon of 13 July, the total had risen to 6,000 according to intercepted radio communication; the following day, Major Franken of Dutchbat was given the same figure by Colonel Radislav Janković of the Serb army. Many prisoners had been seen in the locations described, by passing convoys taking women and children to Kladanj by bus, while aerial photos provided evidence to confirm this.[100][117]

One hour after the evacuation of women from Potočari was complete, the Drina Corps staff diverted the buses to the areas in which the men were being held. Colonel Krsmanović, who on 12 July had arranged the buses for the evacuation, ordered the 700 men in Sandići to be collected, and the soldiers guarding them, made them throw their possessions on a heap and hand over valuables. During the afternoon, the group in Sandići was visited by Mladić who told them they would come to no harm, be treated as prisoners of war, exchanged for other prisoners and their families had been escorted to Tuzla in safety. Some men were placed on transports to Bratunac and other locations, while some were marched to warehouses in Kravica. The men gathered on the pitch at Nova Kasaba were forced to hand over belongings. They too received a visit from Mladić during the afternoon of 13 July; on this occasion, he announced that the Bosnian authorities in Tuzla did not want them and so they were to be taken elsewhere. The men in Nova Kasaba were loaded onto buses and trucks and taken to Bratunac, or other locations.[117]

The Bosnian men who had been separated from the women, children and elderly in Potočari, numbering approximately 1,000, were transported to Bratunac and joined by Bosnian men captured from the column.[118] Almost without exception, the thousands of prisoners captured after the take-over were executed. Some were killed individually, or in small groups, by the soldiers who captured them. Most were killed in carefully orchestrated mass executions, commencing on 13 July, just north of Srebrenica.

The mass executions followed a well-established pattern. The men were taken to empty schools or warehouses. After being detained for hours, they were loaded onto buses or trucks and taken to another site, usually in an isolated location. They were unarmed and often steps were taken to minimise resistance, such as blindfolding, binding their wrists behind their backs with ligatures, or removing their shoes. Once at the killing fields, the men were taken off the trucks in small groups, lined up and shot. Those who survived the initial shooting were shot with an extra round, though sometimes only after they had been left to suffer.[117]

Morning of 13 July: Jadar River

[edit]Prior to midday on 13 July, seventeen men were transported by bus a short distance to a spot on the banks of the Jadar River where they were lined up and shot. One man, after being hit in the hip by a bullet, jumped into the river and managed to escape.[119]

Early afternoon of 13 July: Cerska Valley

[edit]

The first mass executions began on 13 July in the valley of the River Cerska, to the west of Konjević Polje. One witness, hidden among trees, saw 2 or 3 trucks, followed by an armoured vehicle and earthmoving machine proceeding towards Cerska. He heard gunshots for half an hour and then saw the armoured vehicle going in the opposite direction, but not the earthmoving machine. Other witnesses report seeing a pool of blood alongside the road to Cerska. Muhamed Duraković, a UN translator, probably passed this execution site later that day. He reports seeing bodies tossed into a ditch alongside the road, with some men still alive.[120][121]

Aerial photos, and excavations, confirmed the presence of a mass grave near this location. Bullet cartridges, found at the scene, showed that the victims were first lined up on one side of the road, whereupon their executioners shot from the other. The 150 bodies were covered with earth where they lay. It was later established they had been killed by gunfire. All were men, aged 14-50, and all but three was wearing civilian clothes. Many had their hands tied behind their backs. 9 were later identified who were on the list of Srebrenica missing persons list.[120]

Late afternoon of 13 July: Kravica

[edit]Later on 13 July executions were conducted in the largest of four farm sheds, owned by the Agricultural Cooperative in Kravica. Between 1,000 and 1,500 men had been captured in fields near Sandići and detained in Sandići Meadow. They were brought to Kravica, either by bus or on foot, the distance being approximately 1km. A witness recalls seeing around 200 men, stripped to the waist and with their hands in the air, being forced to run in the direction of Kravica. An aerial photo taken at 2pm shows 2 buses standing in front of the sheds.[122]

At around 6pm, when the men were all held in the warehouse, VRS soldiers threw in hand grenades and fired weapons, including rocket propelled grenades. This mass murder seemed "well organised and involved a substantial amount of planning, requiring the participation of the Drina Corps Command".[122]

Supposedly, there was more killing in and around Kravica and Sandići. Even before the murders in the warehouse, some 200 or 300 men were formed up in ranks near Sandići, then executed en masse with concentrated machine gun fire. At Kravica, it was claimed some local men assisted the killings. Some victims were mutilated and killed with knives. The bodies were taken to Bratunac, or simply dumped in the river that runs alongside the road. One witness stated this all took place on 14 July. There were 3 survivors of the mass murder in the farm sheds at Kravica.[122]

Armed guards shot at the men who tried to climb out the windows to escape the massacre. When the shooting stopped, the shed was full of bodies. Another survivor, who was only slightly wounded, reports:

I was not even able to touch the floor, the concrete floor of the warehouse ... After the shooting, I felt a strange kind of heat, warmth, which was coming from the blood that covered the concrete floor and I was stepping on the dead people who were lying around. But there were even men (just men) who were still alive, who were only wounded and as soon as I would step on him, I would hear him cry, moan, because I was trying to move as fast as I could. I could tell that people had been completely disembodied and I could feel bones of the people that had been hit by those bursts of bullets or shells, I could feel their ribs crushing. Then I would get up again and continue.[74]

When this witness climbed out of a window, he was seen by a guard who shot at him. He pretended to be dead and managed to escape the following morning. The other witness quoted above spent the night under a heap of bodies; the next morning, he watched as the soldiers examined the corpses for signs of life. The few survivors were forced to sing Serbian songs and were then shot. Once the final victim had been killed, an excavator was driven in to shunt the bodies out of the shed; the asphalt outside was then hosed down with water. In September 1996, however, it was still possible to find the evidence.[122]

Analyses of hair, blood and explosives residue collected at the Kravica Warehouse provide strong evidence of the killings. Experts determined the presence of bullet strikes, explosives residue, bullets and shell cases, as well as human blood, bones and tissue adhering to the walls and floors of the building. Forensic evidence presented by the ICTY Prosecutor established a link between the executions in Kravica and the 'primary' mass grave known as Glogova 2, in which the remains of 139 people were found. In the 'secondary' grave known as Zeleni Jadar 5, there were 145 bodies, several were charred. Pieces of brick and window frame found in the Glogova 1 grave that was opened later, also established a link with Kravica. Here, the remains of 191 victims were found.[122]

13–14 July: Tišća

[edit]As the buses crowded with Bosnian women, children and elderly made their way from Potočari to Kladanj, they were stopped at Tišća village, searched, and the Bosnian men and boys found on board were removed. The evidence reveals a well-organised operation in Tišća.[123]

From the checkpoint, an officer directed the soldier escorting the witness towards a nearby school where many other prisoners were being held. At the school, a soldier on a field telephone appeared to be transmitting and receiving orders. Around midnight, the witness was loaded onto a truck with 22 other men with their hands tied behind their backs. At one point the truck stopped and a soldier said: "Not here. Take them up there, where they took people before." The truck reached another stopping point and the soldiers came to the back of the truck and started shooting the prisoners. The survivor escaped by running away from the truck and hiding in a forest.[123]

14 July: Grbavci and Orahovac

[edit]A large group of prisoners held overnight in Bratunac were bussed in a convoy of 30 vehicles to the Grbavci school in Orahovica, early on 14 July. When they arrived, the gym was already half-full with prisoners and within a few hours, the building was full. Survivors estimated there were about 2,000 men, some very young, others elderly, although the ICTY Prosecution suggested this maybe an overestimation, with the number closer to 1,000. Some prisoners were taken outside and killed. At some point, a witness recalled, General Mladić arrived and told the men: "Well, your government does not want you and I have to take care of you."[124]

After being held in the gym for hours, the men were led out in small groups to the execution fields that afternoon. Each prisoner was blindfolded and given water as he left. The prisoners were taken in trucks to the fields less than 1km away. The men were lined up and shot in the back; those who survived were killed with an extra shot. Two adjacent meadows were used; once one was full of bodies, the executioners moved to the other. While the executions were in progress, the survivors said earth-moving equipment dug the graves. A witness who survived by pretending to be dead, reported that Mladić drove up in a red car and watched some of the executions.[124]

The forensic evidence supports crucial aspects of the testimony. Aerial photos show the ground in Orahovac was disturbed between 5-27 July and between 7-27 September. Two primary mass graves were uncovered in the area and named Lazete 1 and Lazete 2 by investigators.[124] Lazete 1 was exhumed by the ICTY in 2000. All of the 130 individuals uncovered, for whom sex could be determined, were male; 138 blindfolds were found. Identification material for 23 persons, listed as missing following the fall of Srebrenica, was located during the exhumations. Lazete 2 was partly exhumed by a joint team, from the Office of the Prosecutor and Physicians for Human Rights, in 1996 and completed in 2000. All of the 243 victims associated with Lazete 2 were male, and experts determined most died of gunshot injuries. 147 blindfolds were located.[124] Forensic analysis of soil/pollen samples, blindfolds, ligatures, shell cases and aerial images of creation/disturbance dates, further revealed that bodies, from Lazete 1 and 2, were reburied at secondary graves named Hodžići Road 3, 4 and 5. Aerial images show these secondary gravesites were begun in early September 1995 and all were exhumed in 1998.[124]

14–15 July: Petkovići

[edit]

On 14 and 15 July 1995, another group of prisoners numbering 1,500 to 2,000 were taken from Bratunac to the school in Petkovići. The conditions at the Petkovići school were even worse than Grbavci. It was hot, and overcrowded and there was no food or water. In the absence of anything else, some prisoners chose to drink their urine. Now and then, soldiers would enter the room and physically abuse prisoners or call them outside. A few contemplated an escape attempt, but others said it would be better to stay since the International Red Cross would be sure to monitor the situation and they could not all be killed.[125]

The men were called outside in small groups. They were ordered to strip to the waist and remove their shoes, whereupon their hands were tied behind their backs. During the night of 14 July, the men were taken by truck to the dam at Petkovići. Those who arrived later could see immediately what was happening. Bodies were strewn on the ground, hands tied behind their backs. Small groups of five to ten men were taken out of the trucks, lined up and shot. Some begged for water but their pleas were ignored.[125] A survivor described his feelings of fear combined with thirst:

I was really sorry that I would die thirsty, and I was trying to hide amongst the people as long as I could, like everybody else. I just wanted to live for another second or two. And when it was my turn, I jumped out with what I believe were four other people. I could feel the gravel beneath my feet. It hurt ... I was walking with my head bent down and I wasn't feeling anything. ... And then I thought that I would die very fast, that I would not suffer. And I just thought that my mother would never know where I had ended up. This is what I was thinking as I was getting out of the truck. [As the soldiers walked around to kill the survivors of the first round of shooting] I was still very thirsty. But I was sort of between life and death. I didn't know whether I wanted to live or die anymore. I decided not to call out for them to shoot and kill me, but I was sort of praying to God that they'd come and kill me.[74]

After the soldiers had left, 2 survivors helped each other to untie their hands and crawled over the bodies towards the woods, where they intended to hide. As dawn arrived, they could see the execution site where bulldozers were collecting the bodies. On the way to the execution site, one survivor peeked out from under his blindfold and saw Mladić on his way to the scene.[74]

Aerial photos confirmed the earth near the Petkovići dam had been disturbed and it was disturbed again in late September 1995. When the grave was opened in April 1998, there seemed to be many bodies missing. Their removal had been accomplished with mechanical apparatus, causing considerable disturbance. The grave contained the remains of no more than 43 persons. Other bodies had been removed to a secondary grave, Liplje 2, before 2 October. Here, the remains of at least 191 individuals were discovered.[74]

14–16 July: Branjevo

[edit]On 14 July, more prisoners from Bratunac were bussed northward to a school in Pilica. As at other detention facilities, there was no food or water and several died from heat and dehydration. The men were held at the school for two nights. On 16 July, following a now familiar pattern, the men were called out and loaded onto buses with their hands tied behind their backs, driven to the Branjevo Military Farm, where groups of 10 were lined up and shot.[126]

Dražen Erdemović—who confessed to killing at least 70 Bosniaks—was a member of the VRS 10th Sabotage Detachment. Erdemović appeared as a prosecution witness and testified: "The men in front of us were ordered to turn their backs ... we shot at them. We were given orders to shoot."[127] On this point, a survivors recalls:

When they shot, I threw myself on the ground ... one man fell on my head. I think that he was killed on the spot. I could feel the hot blood pouring over me ... I could hear one man crying for help. He was begging them to kill him. And they simply said "Let him suffer. We'll kill him later."

— Witness Q[128]

Erdemović said nearly all the victims wore civilian clothes and, except for one person who tried to escape, offered no resistance. Sometimes the executioners were particularly cruel. When some soldiers recognised acquaintances, they beat and humiliated them, before killing them. Erdemović had to persuade fellow soldiers to stop using machine guns; while it mortally wounded the prisoners, it did not cause death immediately and prolonged their suffering.[127] Between 1,000 and 1,200 men were killed in that day at this execution site.[129]

Aerial photos, taken on 17 July of an area around the Branjevo Military Farm, show many bodies lying in a field, as well as traces of the excavator that collected the bodies.[130] Erdemović testified that, at around 3pm on 16 July, after he and fellow soldiers from the 10th Sabotage Detachment had finished executing prisoners at the Farm, they were told there was a group of 500 Bosnian prisoners from Srebrenica, trying to break out of a Dom Kultura club. Erdemović and other members of his unit refused to carry out more killings. They were told to meet with a Lieutenant Colonel at a café in Pilica. Erdemović and his fellow soldiers travelled to the café and, as they waited, could hear shots and grenades being detonated. The sounds lasted 15–20 minutes after which a soldier entered the café to inform them "everything was over".[131]

There were no survivors to explain exactly what happened in the Dom Kultura.[131] The executions there were remarkable as this was not remote, but a town centre on the main road from Zvornik to Bijeljina.[132] Over a year later, it was still possible to find physical evidence of this crime. As in Kravica, many traces of blood, hair and body tissue were found in the building, with cartridges and shells littered throughout the two storeys.[133] It could be established that explosives and machine guns had been used. Human remains and personal possessions were found under the stage, where blood had dripped down through the floorboards.

Two of the three survivors of the executions at the Branjevo Military Farm, were arrested by Bosnian Serb police on 25 July and sent to the prisoner of war compound at Batkovici. One had been a member of the group separated from the women in Potočari on 13 July. The prisoners who were taken to Batkovici survived[134] and testified before the Tribunal.[135]

Čančari Road 12 was the site of the reinterment of at least 174 bodies, moved from the mass grave at the Branjevo Military Farm.[136] Only 43 were complete sets of remains, most of which established that death was due to rifle fire. Of the 313 body parts found, 145 displayed gunshot wounds of a severity likely to prove fatal.[137]

14–17 July: Kozluk

[edit]

The exact date of the executions at Kozluk is unknown, though most probably 15-16 July, partly due to its location, between Petkovići Dam and the Branjevo Military Farm. It falls within the pattern of ever more northerly execution sites: Orahovac on 14 July, Petkovići Dam on 15 July, the Branjevo Military Farm and Pilica Dom Kultura on 16 July.[138] Another indication is that a Zvornik Brigade excavator spent 8 hours in Kozluk on 16 July and a truck belonging to the same brigade made two journeys between Orahovac and Kozluk that day. A bulldozer is known to have been active in Kozluk on 18 and 19 July.[139]

Among Bosnian refugees in Germany, there were rumours of executions in Kozluk, during which 500 or so prisoners were forced to sing Serbian songs as they were being transported to the execution site. Though no survivors have come forward, investigations in 1999 led to the discovery of a mass grave near Kozluk.[140] This proved to be the location of execution as well, and lay alongside the Drina accessible only by driving through the barracks occupied by the Drina Wolves, a police unit of Republika Srpska. The grave was not dug specifically for the purpose: it had previously been a quarry and landfill site. Investigators found many shards of glass which the nearby 'Vitinka' bottling plant had dumped there. This facilitated the process of establishing links with the secondary graves along Čančari Road.[141] The grave at Kozluk had been partly cleared before 27 September 1995, but no fewer than 340 bodies were found there.[142] In 237 cases, it was clear they had died as the result of rifle fire: 83 by a single shot to the head, 76 by one shot through the torso region, 72 by multiple bullet wounds, five by wounds to the legs and one by bullet wounds to the arm. Their ages were between 8 and 85. Some had been physically disabled, occasionally as the result of amputation. Many had been tied and bound using strips of clothing or nylon thread.[141]

Along the Čančari Road are twelve known mass graves, of which only two—Čančari Road 3 and 12—have been investigated in detail (as of 2000[update]).[143] Čančari Road 3 is known to have been a secondary grave linked to Kozluk, as shown by the glass fragments and labels from the Vitinka factory.[144] The remains of 158 victims were found here, of which 35 bodies were more or less intact and indicated most had been killed by gunfire.[145]

13–18 July: Bratunac-Konjević Polje road

[edit]On 13 July, near Konjević Polje, Serb soldiers summarily executed hundreds of Bosniaks, including women and children.[146] The men found attempting to escape by the Bratunac-Konjević Polje road were told the Geneva Convention would be observed if they gave themselves up.[147] In Bratunac, men were told there were Serbian personnel standing by to escort them to Zagreb for a prisoner exchange. The visible presence of UN uniforms and vehicles, stolen from Dutchbat, were intended to contribute to the feeling of reassurance. On 17 to 18 July, Serb soldiers captured about 150–200 Bosnians in the vicinity of Konjevic Polje and summarily executed about one-half.[146]

18–19 July: Nezuk–Baljkovica frontline

[edit]After the closure of the corridor at Baljkovica, groups of stragglers nevertheless attempted to escape into Bosnian territory. Most were captured by VRS troops in the Nezuk–Baljkovica area and killed on the spot. In the vicinity of Nezuk, about 20 small groups surrendered to Bosnian Serb military forces. After the men surrendered, soldiers ordered them to line up and summarily executed them.[92]

On 19 July, for example, a group of approximately 11 men was killed at Nezuk itself by units of the 16th Krajina Brigade, then operating under the direct command of the Zvornik Brigade. Reports reveal a further 13 men, all ARBiH soldiers, were killed at Nezuk on 19 July.[148] The report of the march to Tuzla includes the account of an ARBiH soldier who witnessed executions carried out by police. He survived because 30 ARBiH soldiers were needed for an exchange of prisoners following the ARBiH's capture of a VRS officer at Baljkovica. The soldier was exchanged in late 1995; at that time, there were still 229 men from Srebrenica in the Batkovici prisoner of war camp, including two who had been taken prisoner in 1994.[citation needed]

RS Ministry of the Interior forces searching the terrain from Kamenica as far as Snagovo killed eight Bosniaks.[149] Around 200 Muslims armed with automatic and hunting rifles were reported to be hiding near the old road near Snagovo.[149] During the morning, about 50 Bosniaks attacked the Zvornik Brigade line in the area of Pandurica, attempting to break through to Bosnian government territory.[149] The Zvornik Public Security Centre planned to surround and destroy these two groups the following day using all available forces.[150]

20–22 July: Meces area

[edit]According to ICTY indictments of Karadžić and Mladić, on 20 to 21 July near Meces, VRS personnel, using megaphones, urged Bosniak men who had fled Srebrenica to surrender and assured them they would be safe. Approximately 350 men responded to these entreaties and surrendered. The soldiers then took approximately 150, instructed them to dig their graves and executed them.[151]

After the massacre

[edit]

During the days following the massacre, US spy planes overflew Srebrenica and took photos showing the ground in vast areas around the town had been removed, a sign of mass burials.

On 22 July, the commanding officer of the Zvornik Brigade, Lieutenant Colonel Vinko Pandurević, requested the Drina Corps set up a committee to oversee the exchange of prisoners. He asked for instructions on where the prisoners of war his unit had already captured should be taken and to whom they should be handed over. Approximately 50 wounded captives were taken to the Bratunac hospital. Another group was taken to the Batkovići camp, and these were mostly exchanged later.[152] On 25 July, the Zvornik Brigade captured 25 more ARBiH soldiers who were taken directly to the camp at Batkovići, as were 34 ARBiH men captured the following day. Zvornik Brigade reports up until 31 July continue to describe the search for refugees and the capture of small groups of Bosniaks.[153]

Several Bosniaks managed to cross over the River Drina into Serbia at Ljubovija and Bajina Bašta. 38 were returned to RS. Some were taken to the Batkovići camp, where they were exchanged. The fate of the majority has not been established.[152] Some attempting to cross the Drina drowned.[152]

By 17 July, 201 Bosniak soldiers had arrived in Žepa, exhausted and many with light wounds.[152] By 28 July another 500 had arrived in Žepa from Srebrenica.[152][154] After 19 July, small Bosniak groups were hiding in the woods for days and months, trying to reach Tuzla.[152] Numerous refugees found themselves cut off in the area around Mount Udrc.[155][156] They did not know what to do next or where to go; they managed to stay alive by eating vegetables and snails.[155][156] The MT Udrc had become a place for ambushing marchers, and the Bosnian Serbs swept through and, according to one survivor, killed many people there.[155][156]

Meanwhile, the VRS had commenced the process of clearing the bodies from around Srebrenica, Žepa, Kamenica and Snagovo. Work parties and municipal services were deployed to help.[156][157] In Srebrenica, the refuse that had littered the streets since the departure of the people was collected and burnt, the town disinfected and deloused.[156][157]

Wanderers

[edit]Many people in the part of the column which had not succeeded in passing Kamenica, did not wish to give themselves up and decided to turn back towards Žepa.[158] Others remained where they were, splitting up into smaller groups of no more than ten.[159] Some wandered around for months, either alone or groups of two, four or six men.[159] Once Žepa had succumbed to the Serb pressure, they had to move on once more, either trying to reach Tuzla or crossing the River Drina into Serbia.[160]

Zvornik 7

[edit]The most famous group of seven men wandered about in occupied territory for the entire winter. On 10 May 1996, after 9 months on the run and over six months after the end of the war, they were discovered in a quarry by American IFOR soldiers. They immediately turned over to the patrol; they were searched and their weapons were confiscated. The men said they had been in hiding near Srebrenica since its fall. They did not look like soldiers and the Americans decided this was a matter for the police.[161] The operations officer of the American unit ordered that a Serb patrol should be escorted into the quarry whereupon the men would be handed over to the Serbs.

The prisoners said they were initially tortured after the transfer, but later treated relatively well. In April 1997 the local court in Republika Srpska convicted the group, known as the Zvornik 7, for illegal possession of firearms and three of them for the murder of four Serbian woodsmen. When announcing the verdict the presenter of the TV of Republika Srpska described them as "the group of Muslim terrorists from Srebrenica who last year massacred Serb civilians".[162] The trial was condemned by the international community as "a flagrant miscarriage of justice",[163][164] and the conviction quashed for 'procedural reasons' following international pressure. In 1999, the three remaining defendants in the Zvornik 7 case were swapped for three Serbs serving 15 years each in a Bosnian prison.

Reburials in the secondary mass graves

[edit]

From August to October 1995, there was organised effort to remove the bodies from primary gravesites and transport them to secondary and tertiary gravesites.[165] In the ICTY court case Prosecutor v. Blagojević and Jokić, the trial chamber found that this reburial effort was an attempt to conceal evidence of the mass murders.[166] The trial chamber found that the cover-up operation was ordered by the VRS Main Staff and carried out by members of the Bratunac and Zvornik Brigades.[166]

The cover-up had a direct impact on the recovery and identification of the remains. The removal and reburial of the bodies caused them to become dismembered and co-mingled, making it difficult for forensic investigators to positively identify the remains.[167] In one case, the remains of a single person were found in two locations, 30 km apart.[168][failed verification] In addition to the ligatures and blindfolds found, the effort to hide the bodies has been seen as evidence of the organised nature of the massacres and the non-combatant status of the victims.[167][169]

Greek Volunteers controversy

[edit]10 Greek volunteers fought alongside the Serbs in the fall of Srebrenica.[170][171] They were members of the Greek Volunteer Guard, a contingent of paramilitaries requested by Mladić, as an integral part of the Drina Corps. The volunteers were motivated to support their "Orthodox brothers" in battle.[172] They raised the Greek flag at Srebrenica, at Mladić's request, to honour "the brave Greeks fighting on our side"[173] and Karadžić decorated four.[174][175][176][177] In 2005, Greek deputy Andrianopoulos called for an investigation,[178] Justice Minister Papaligouras commissioned an inquiry[179] and in 2011, a judge said there was insufficient evidence to proceed.[171] In 2009, Stavros Vitalis announced the volunteers were suing Takis Michas for libel over allegations in his book Unholy Alliance, which described Greece's support for the Serbs during the war. Insisting the volunteers had simply taken part in the "re-occupation" of Srebrenica, Vitalis was present with Serb officers in "all military operations".[180][181][182]

Post-war developments

[edit]1995–2000: Indictments and UN Secretary-General's report

[edit]In November 1995 Karadžić and Mladić were indicted by the ICTY for their alleged direct responsibility for the war crimes committed against the Bosnian Muslim population of Srebrenica.[59] In 1999, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan submitted his report on the Fall of Srebrenica. He acknowledged the international community as a whole had to accept its share of responsibility, for its response to the ethnic cleansing that culminated in the murder of 7,000 unarmed civilians from the town designated by the Security Council as a "safe area".[59][183][184]

2002: Dutch government report