State microbe

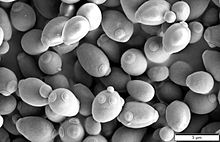

A state microbe is a microorganism used as an official state symbol. Several U.S. states have honored microorganisms by nominating them to become official state symbols. The first state to declare an Official State Microbe is Oregon which chose Saccharomyces cerevisiae (brewer's or baker's yeast) as the Official Microbe of the State of Oregon in 2013 for its significance to the craft beer industry in Oregon.[1] One of the first proponents of State Microbes was microbiologist Moselio Schaechter, who, in 2010, commented on Official Microbes for the American Society for Microbiology's blog "Small Things Considered"[2] as well as on National Public Radio's "All Things Considered".[3][4]

Wisconsin 2009: Lactococcus lactis, proposed, not passed

[edit]

In November 2009, Assembly Bill 556 that proposed designating Lactococcus lactis as Wisconsin state microbe was introduced by Representatives Hebl, Vruwink, Williams, Pasch, Danou, and Fields; it was cosponsored by Senator Taylor.[5] Although the bill passed the Assembly 56 to 41, It was not acted on by the Senate.[6] The proposed AB 556 simply stated that Lactococcus lactis is the State Microbe and should be included in the Wisconsin Blue Book,[7] an almanac containing information on the state of Wisconsin, published by Wisconsin's Legislative Reference Bureau.

Lactococcus lactis was proposed as the State Microbe because of its crucial contribution to the cheese industry in Wisconsin. Wisconsin is the largest cheese producer in the United States, producing 3.1 billion pounds of cheese, 26% of all cheese in the US, in more than 600 varieties (2017 data).[8]

Lactococcus lactis is vital for manufacturing cheeses such as Cheddar, Colby, cottage cheese, cream cheese, Camembert, Roquefort, and Brie, as well as other dairy products like cultured butter, buttermilk, sour cream, and kefir. It may also be used for vegetable fermentations such as cucumber pickles and sauerkraut.[9]

Hawaiʻi 2013–14: Flavobacterium akiainvivens and/or Aliivibrio fischeri

[edit]

In January 2013, House Bill 293 was introduced by State Representative James Tokioka; the proposed bill designates Flavobacterium akiainvivens as the State Microbe of Hawaiʻi.[10] The bacterium was discovered on a decaying ʻākia shrub by Iris Kuo, a high school student working with Stuart Donachie at the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa.[11][12] The Hawaiʻian context is strong here because the ʻākia shrub (Wikstroemia oahuensis) is native to Hawaiʻi, and the microbe (Flavobacterium akiainvivens) was first found in Hawaiʻi. The shrub was used by ancient Hawaiʻians for medicine, textiles and for catching fish, while the microbe may have antibiotic properties.[10]

Although it was favored by the House, the Flavobacterium akiainvivens bill failed to get a hearing in the Senate Technology and Arts Committee (TEC) and could not move forward for a Senate vote.[13]

In February 2014, Senate Bill 3124 was introduced by Senator Glenn Wakai; the bill designates Aliivibrio fischeri as the State Microbe of Hawaiʻi.[14][15] Senator Wakai was Chairman of the Senate Technology and Arts Committee that squashed the Flavobacterium legislation. Aliivibrio fischeri was selected because it lives in a symbiotic relationship with the native Hawaiʻian bobtail squid, in which it confers bioluminescence on the squid, enabling it to hunt at night.[15] Although this is an awesome example of symbiosis, political and scientific controversy erupted because even though the bobtail squid is only found in Hawaiʻi, Aliivibrio fischeri can be found elsewhere.[16][17]

The combined Hawaiʻian Legislature could not agree on which microbe better suited Hawaiʻi, and the proposed legislation was dropped.[18]

Legislation proposing Flavobacterium akiainvivens as the state microbe was re-introduced in 2017 ().

Oregon 2013: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, passed

[edit]

Oregon was the first state to declare an Official State Microbe.

In February 2013, House Concurrent Resolution 12 (HCR-12) was introduced into the Oregon legislative system by Representative Mark Johnson; the bill designates Saccharomyces cerevisiae (brewer's yeast or bakers yeast) as the Official Microbe of the State of Oregon.[19] The bill was passed by unanimous vote in the House on April 11; it passed in the Senate by a vote of 28 to 2 on May 23.[20] Cosponsors of the measure were: Representatives Dembrow, McLane, Vega Pederson, Whisnant, Williamson, and Senators Hansell, Prozanski, and Thomsen.[20]

HCR-12 recognizes the history of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in baking and brewing, thanks to its ability to convert fermentable sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide. Most important for Oregon is that the microbe is essential to the production of alcoholic beverages such as mead, wine, beer, and distilled spirits. Moreover, Saccharomyces cerevisiae inspired the thriving brew culture in Oregon, making Oregon an internationally recognized hub of craft brewing.[21] The craft brewing business brings Oregon $2.4 billion annually, thanks to brewers yeast and talented brewers.[22]

New Jersey 2017–2019: Streptomyces griseus, signed into law May 10, 2019

[edit]

Introduction

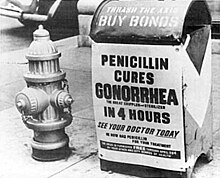

[edit]Streptomyces griseus was chosen for the honor of becoming the New Jersey State Microbe because the organism is a New Jersey native that made unique contributions to healthcare and scientific research worldwide. A strain of S. griseus that produced the antibiotic streptomycin was discovered in New Jersey in “heavily manured field soil” from the New Jersey Agricultural Experimental Station by Albert Schatz in 1943.[23] Streptomycin is noteworthy because it is: the first significant antibiotic discovered after penicillin; the first systemic antibiotic discovered in America; the first antibiotic active against tuberculosis; first-line treatment for plague. Moreover, New Jersey was the home of Selman Waksman, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his systematic studies of antibiotic production by S. griseus and other soil microbes.[24]

Legislative Activity

[edit]On May 15, 2017, Senate Bill 3190 (S3190) was introduced by Senator Samuel D. Thompson (R-12); the bill designates Streptomyces griseus as the New Jersey State Microbe, to be added to the state's other state symbols. On June 1, 2017 Assemblywoman Annette Quijano (D-20) introduced Assembly Bill 4900 (A4900); the bill also designates S. griseus as the New Jersey State Microbe, and is the Assembly counterpart of S3190.[25]

On December 11, 2017 (the birthday of Dr Robert Koch) S3190 was unanimously approved by the NJ Senate State Government. Wagering, Tourism & Historic Preservation Committee. Speaking on behalf of the State Microbe were Drs John Warhol, Douglas Eveleigh,[26] and Max Haggblom.[27] On January 8, 2018, the full New Jersey Senate unanimously approved (38 to 0) S3190.[28] The Assembly did not act on its version of the State Microbe legislation.

State Microbe legislation was reintroduced in the New Jersey Senate on February 5, 2018, by Senator Samuel Thompson (R-12); the bill number is S1729.[29] Similar legislation was reintroduced in the New Jersey Assembly on March 12, 2018; the bill number is A3650. The legislation is sponsored by Assemblywoman Annette Quijano (D-20), ASW Patricia Jones (D-5), Assemblyman Arthur Barclay (D-5), ASM Eric Houghtaling (D-11), and ASW Joann Downey (D-11).[30]

On June 14, 2018, Senate Bill S1729 was unanimously approved by the NJ Senate State Government, Wagering, Tourism & Historic Preservation Committee.[31] On July 27, 2018, Senate Bill S1729 was unanimously approved (33 to 0) by the full New Jersey Senate.[32] From the well of the Senate, Senator Thompson kindly acknowledged the efforts of State Microbe advocates John Warhol, Douglas Eveleigh, Jeff Boyd, and Jessica Lisa.

On September 17, 2018, Assembly Bill A3650 was unanimously approved by the Assembly Science, Innovation, and Technology Committee.[33] Testifying on behalf of the State Microbe were Drs John Warhol, Douglas Eveleigh, and Jeff Boyd.[33] On February 25, 2018, The New Jersey Assembly unanimously approved S1729/A3650 by a vote of 76 to 0.[34]

The final vote in the Senate was March 14, 2019.[35] The Bill passed by a vote of 34 to 0.[36]

On May 10, 2019, Governor Murphy signed S1729/A3650 into effect.[37] This made New Jersey the second state to have an Official Microbe, and the first to have an Official Bacterium.

Education Activity

[edit]The Rutgers University School of Environmental and Biological Science (SEBS) Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology hosted a poll for New Jersey State Microbe. The candidates have been Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans (discovered in NJ, 1922), Azotobacter vinelandii (discovered in Vineland, 1903), and Streptomyces griseus (New Brunswick is home of the streptomycin-producing strain).[38] S. griseus has been the winning microbe by a 3 to 1 margin. In 2018, they received hundreds of signatures on a petition urging legislators to recognize S. griseus as the State Microbe.

The New Jersey State Microbe was the subject of a presentation by John Warhol at the 2018 Rutgers University Microbiology Symposium.[39][40] Dr Warhol also spoke about the New Jersey State Microbe at the Theobald Smith Society (NJ Chapter of the American Society for Microbiology) Meeting in Miniature at Seton Hall University in April 2018.[41]

A scientific paper on the political and social process of designating an official state microbe was presented at Microbe 2018, the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.[42] Titled "How to Get Your Own Official State Microbe" the presentation stressed the importance of clear communication and legislator contact by academic, industrial, and student supporters. The authors were Max Haggblom, Douglas Eveleigh, and John Warhol.

In November 2018, the New Jersey Historical Commission Forum on New Jersey History at Monmouth University was the venue for two presentations on the State Microbe. The first was titled "An Official New Jersey State Microbe! Streptomyces griseus" and the second was "The 75th Anniversary of the Discovery of Streptomycin – 2019". Authors of the presentations were Douglas Eveleigh, Jeff Boyd, Max Haggblom, Jessica Lisa, and John Warhol.[43][44]

In early November 2018, Rutgers University launched a web page recognizing the Selman Waksman Museum at the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences.[45] The museum is housed in Dr Waksman's former laboratory space in Martin Hall.[46]

The Eagleton Institute of Politics hosted a Science and Policy Workshop titled "Scientists in Politics" in late November 2018.[47] Douglas Eveleigh and John Warhol participated, and informed the attendees about the history of microbiology in New Jersey and the importance of the State Microbe as a scientific and cultural symbol for New Jersey.

The Liberty Science Center (LSC) opened a new exhibit on December 13 named "Microbes Rule!"[48] The installation features interactive learning stations in which museum-goers can discover the many ways that microbes shape life on Earth. The New Jersey State Microbe has a prominent place in the exhibit; Liberty Science Center sponsored a petition for the NJ legislature to vote Yes on behalf of the State Microbe.[49] Speaking at the opening ceremony for the exhibit were LSC Chief Executive Officer Paul Hoffman, NJ Assemblyman Andrew Zwicker, Rutgers University Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology Chairman Max Haggblom,[27] Merck Executive Director for Infectious Diseases Todd Black,[50] American Society for Microbiology Outreach Manager Dr Katherine Lontok, and science author Dr John Warhol of The Warhol Institute.

Press and Media Coverage

[edit]Following the Senate vote, The New Jersey State Microbe was the subject of local, national, and international media attention. Streaming audio and video interviews were broadcast or posted with Drs Eveleigh, Boyd, Warhol, and Haggblom on CBS News,[51] News 12 New Jersey,[52] NPR,[53] This Week In Microbiology,[54] and KYWNews Radio.[55] Electronic and print media coverage included the Asbury Park Press,[56] NorthJersey.com,[57] The Philadelphia Inquirer,[58] NJ.com,[57][59] NJ 101.5 dot com,[60] NJ Spotlight,[61] WPG Talk Radio,[62] Rutgers Today,[63] Politico,[64] WSUS,[65] Sky News,[66] and Isle of Wight Radio.[66]

On November 30, 2018, Jeff Boyd was featured on the cover of the Daily Targum in an article titled "Rutgers Professors Nominate Tuberculosis-Curing Bacteria for Official State Microbe".[67] The story summarized the reasons for the State Microbe (saves lives, creates jobs) and the work that scientists have done to get the microbe recognized by the state legislature. Dr Boyd pointed out that “Microbes shape every aspect of our lives, our environment and the earth” and certainly deserve more recognition. Dr Eveleigh was also interviewed for the article and said "I’d like the governor to sign the legislation in the room of the lab in which streptomycin was discovered.”

On December 13, 2018, the State Microbe was highlighted in press and broadcast coverage by NJTV News[68] of the opening of Microbes Rule! at the Liberty Science Center.

On Feb 21, Dr Jeffrey Boyd spoke with NJ Monthly for an article titled "Not Your Average Germ: New Jersey Considers a State Microbe".[69]

On February 26, 2018, after the Assembly vote, Dr John Warhol was interviewed by Rebeca Ibarra[70] of National Public Radio/WNYC for comments about the new State Microbe.[71]

After Governor Murphy signed the State Microbe bill into law on May 10, 2019, additional press coverage developed in a variety of outlets.[72][73][74]

The New Jersey State Microbe was featured in two televised interviews in July 2019. The first was on CUNY TV's[75] Simply Science hosted by Barry Mitchell "Meet the New Jersey Microbe" featured an inspired Garden State Microbe song rendition on the steps of Dr Waksman's original laboratory. Drs Boyd and Haggblom recounted the story of The New Jersey State Microbe and the importance of microbes in everyday life on Earth.[76] Dr Warhol appeared on Jersey Matters[77] hosted by Larry Mendtke. In the segment titled "Jersey Matters-State Microbe", they discussed the importance of the New Jersey State Microbe and the growing need for improved microbe education and awareness.[78]

Hawaii 2017: Flavobacterium akiainvivens, pending

[edit]In 2017, legislation similar to the original 2013 bill to make Flavobacterium akiainvivens the state microbe was submitted in the Hawaiʻi House of Representatives by Isaac Choy[79] and in the Hawaiʻi Senate by Brian Taniguchi.[80] In January 2017, Representative Choy submitted HB 1217 in the Hawaiʻi House of Representatives and Senator Taniguchi submitted the mirror bill SB1212 in the Hawaiʻi Senate. This continues the effort started by James Tokioka in 2013, and later contested in 2014 by Senator Glenn Wakai's SB3124 bill proposing Aliivibrio fischeri instead. As of December 2017[update], Hawaiʻi has no official state microbe.

Illinois 2019: Penicillium rubens NRRL 1951, passed May 31, 2021, signed into Law August 17, 2021

[edit]Introduction

[edit]

The world's first antibiotic, penicillin, is produced by a strain of the mold Penicillium rubens (formerly Penicillium chrysogenum). Though the history of penicillin is centuries long, Scottish physician Alexander Fleming is usually credited with initiating the modern era of penicillin discovery, research, and development when he found the mold (Penicillium notatum, now also P. rubens) growing on a culture plate in his laboratory in 1928. Penicillin is effective on gram-positive bacteria. The antibiotic-producing strains of Penicillium in the early years produced relatively low yields of unstable penicillin. The yields were so low that urine from treated patients was collected and the penicillin remaining extracted and reused. At Oxford University in England a team including Dr. Howard Florey, Dr. Ernst Chain and Norman Heatley took up the goal of finding solutions to penicillin recovery issues. After a referral on who best to contact about increasing production, Florey and Heatley secretly came to Peoria Illinois on July 14, 1941, with their penicillin producing mold. WW2 necessitated moving of the work on penicillin to the United States where industrial supplies were not as constrained for the war effort. They met with personnel at the USDA (then Northern Regional Research Laboratory, NRRL, now National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, NCAUR). There at the "Ag Lab" corn steep liquor, a byproduct of alcohol production, had been used for growing mold cultures in the past. It was found out later that phenylacetic acid, a side chain precursor of penicillin was present in quantity in the liquor and had increased yields. Other additions to the growth media such as lactose(milk sugar) were restricted during the war for penicillin production. Major breakthroughs at the Ag Lab came in the years between 1941 and 1943, when higher yielding strains were isolated. After the isolation trials selected the most promising mold strains, methods for the industrialized production of penicillin were developed there in Peoria, Illinois. The strain having the highest production was found on a moldy cantaloupe in Peoria, IL. This strain was improved upon by research at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (formerly the Carnegie Institution of Washington) and the University of Wisconsin. Strains were given out to other researchers and interested industrial firms. The mass production techniques developed at the Ag Lab enabled the United States and its allies to have penicillin available for the D-Day invasion in 1944. After an initial few, eventually about twenty industrial partners helped increase the yields of penicillin. On March 15, 1945, penicillin was made available to the public after being available some months before to hospitals and doctors.

Origin of the idea of an Illinois State Microbe

[edit]On August 7, 2018, while driving home and listening to National Public Radio's broadcast of "All Things Considered," Gary Kuzniar heard an interesting story about State Microbe designations. The story said that Oregon had already passed legislation (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and other states had started working to declare theirs. The next month Dr. Neil Price was walking in the hallway with two petri dish plasticized mold props and Gary asked him what they were. Neil said that they were penicillin props for a display in "The Ten Most Important Medical Inventions of the World" down at the local museum(Peoria Riverfront Museum). Gary mentioned that he had heard a radio program on state microbes and that the penicillin he had in his hands would be a good candidate for Illinois. It was agreed between them to form the Illinois State Microbe Designation Project to approach the whole logistical thing of doing it.

Legislative activity

[edit]On February 15, 2019, Senator Dave Koehler introduced SB 1857, legislation that designates Penicillium chrysogenum NRRL 1951 as the Official State Microbe of Illinois.[81] The bill passed the Senate on April 4 and gained Senator Mattie Hunter as a cosponsor. That same day, the bill was introduced into the Illinois House of Representatives with Rep. Jehan Gordon-Booth as the primary sponsor. The bill was then referred to the State Rules Committee on 4 April 2019 and later to the State Government Administration Committee on 24 April. During the Spring 2019 Illinois Legislative session, it was learned that current DNA analysis on the famous Penicillium chrysogenum strain from the 1940s resulted in a name change to P. rubens. The original nomenclature was based on physical structure and current science relies on the more precise DNA analysis. The senate bill appeared on the 2019 Fall Veto Session docket but it didn't make it to the floor. SB 1857 was considered again in the 2020 Illinois State Spring Pandemic Session but COVID-19 made the session short. The bill was emptied of its contents, other considerations inserted and the bill passed quickly. There was no Fall 2020 Illinois State House Veto Session due to the continuing COVID-19 restrictions. At the start of the 2021 Illinois General Assembly Spring Session parallel bills were started, SB 2004 in the Senate and HB 1879 in the House for an Illinois State Microbe. Again there was a delay in the bill moving and the House bill survived to go forward. The Friday before the end of the session saw this bill amended just three days before the end of the Spring Session. On the last day of the official 2021 Illinois General Assembly Spring Session, about 8:10 pm on the evening of May 31, 2021 the bill HB 1879 designating Penicillium rubens as Illinois' State Microbe was brought up by Representative Ryan Spain and was passed. It then was forwarded to the desk of Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker on June 29, 2021, to be signed. After about a month and a half the bill was then signed in a public ceremony at the University of Illinois Springfield Campus on August 17, 2021, with the . In the Spring 2021 Session, new bills were introduced in both the IL Senate and House to denote an Illinois State Microbe (SB 2004 and HB1879). The IL House bill survived and was concurred with the IL Senate proceedings. It passed both State Houses on May 31, 2021

Press and media coverage

[edit]Press coverage for the Illinois State Microbe has been enthusiastic. Journalist Phil Luciano of the Journal Star interviewed Neil Price of the National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research. As a representative of the Illinois State Microbe Designation Project he contactied Senator David Koehler and relayed information about the crucial role that Illinois had in the production of penicillin and its effect on world health.[82] He then gave a witness testimony to the Illinois Senate on March 20, 2019. Additional television coverage was featured on WQAD-TV.[83]

Promotion, Contact of and Support Letters and Legislation

Gary took this aspect of the project and contacted two people that were currently working for New Jersey's State Microbe (Streptomyces griseous), Dr. Max Haggblom and Dr. John Warhol. Letters of support were requested and put in a folder to be given to the original introducer of an Illinois State Microbe bill (Senator Koehler), each local district legislator and professional organizations throughout the state. Some of the letters were received from Western Illinois University, University of Wisconsin at Madison, Bradley University in Peoria Illinois and the William Dunn School of Pathology at the University of Oxford where the original work by Alexander Fleming was noticed and continued by scientists Howard Florey, Ernst Chain, Norman Heatley and others. Small Penicillium plushes from Giant Microbes were attached to folders containing the letters of support and then given to local legislators and others along with a cantaloupe. A T-shirt has been made that includes an illustration from the Manual of Penicillia by Dr. Kenneth B. Raper and Charles Thom. One of the illustrations done by Dorothy I. Fennell was selected. She worked under Dr. Raper. Permission for this was granted by the book publisher. During the legislation, a painting of an iconic character and one of its commissioner were obtained from the University of Wisconsin at Madison with permission of the Bacteriology Department. "Moldy Mary" is a painting of a young woman at a 1940s downtown Peoria Illinois produce market with a moldy cantaloupe in her hand. The second painting is of the paintings' commissioner himself, Dr. Ken Raper. He is standing in a lab also with a cantaloupe in his hand. Both were available for viewing at the "Ten Most Important Medical Inventions of the World" exhibit at the Peoria Riverfront Museum earlier 2019.

See also

[edit]- Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus the National Microbe for India[84]

References

[edit]- ^ Morgan, Jason (April 8, 2013). "Oregon first to name official state yeast". Craft Brewing Business.

- ^ "State Microbes". Small Things Considered. Retrieved 2018-09-16.

- ^ "A State Microbe For Cheese-Crazed Wisconsin?". NPR.org. Retrieved 2018-09-16.

- ^ "No State Microbe For Wisconsin". NPR.org. Retrieved 2018-09-16.

- ^ "2009 Assembly Bill 556". docs.legis.wisconsin.gov. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ^ Davey, Monica (2010-04-15). "Wisconsin Legislators Approve State Microbe". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ^ "2009 Assembly Bill 556" (PDF).

- ^ "2017 Wisconsin Dairy Data" (PDF).

- ^ "Lactococcus lactis Wisconsin State Microbe". advanced.bact.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ^ a b "Hana Hou: The Magazine of Hawaiian Airlines – Current Issue". www.hanahou.com. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ^ Torrice, Michael. "Computers Play Super Mario, States Adopt Microbes | May 13, 2013 Issue – Vol. 91 Issue 19 | Chemical & Engineering News". cen.acs.org. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ^ Kuo, Iris; et al. (2013). "Flavobacterium akiainvivens sp. nov., from decaying wood of Wikstroemia oahuensis , Hawai'i, and emended description of the genus Flavobacterium". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 63 (Pt 9): 3280–3286. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.047217-0. PMID 23475344.

- ^ "Competing to be Hawaii's top microbe – Hawaii Reporter". Hawaii Reporter. 2014-01-28. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ^ "Bill to Make Hawaiian Bobtail Squid Hawaii's Official State Microbe to be Heard Tomorrow". Hawaii News and Island Information. 2014-02-25. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ^ a b Wakai, Glenn. "SB3124 Hawaiian Senate Bill, 2014" (PDF).

- ^ "State Microbe for Hawaii". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ^ "Vibrio fischeri NEU2011 – microbewiki". microbewiki.kenyon.edu. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ^ Cave, James (2014-04-03). "Hawaii, Other States Calling Dibs On Official State Bacteria". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ^ "Oregon is first in nation with official state microbe: brewer's yeast". OregonLive.com. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- ^ a b "Tracking House Concurrent Resolution 12 in the Oregon Legislature". Your Government :: The Oregonian. Retrieved 2017-11-21.

- ^ "Enrolled House Concurrent Legislation 12".

- ^ "Ale Yeast Running For Official State Microbe Of Oregon". Popular Science. Retrieved 2017-11-28.

- ^ Schatz A, Bugie E, Waksman SE. (1944). "Streptomycin, a Substance Exhibiting Antibiotic Activity Against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 55: 66–69.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1952". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

- ^ "A4900". www.njleg.state.nj.us. Retrieved 2017-11-28.

- ^ "Douglas E. Eveleigh Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology at Rutgers SEBS". dbm.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ a b "Max Häggblom Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology at Rutgers SEBS". dbm.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ "New Jersey Legislature – Bills". www.njleg.state.nj.us. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

- ^ "New Jersey S1729 | 2018–2019 | Regular Session". LegiScan. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- ^ "New Jersey A3650 | 2018–2019 | Regular Session". LegiScan. Retrieved 2018-04-13.

- ^ "New Jersey S1729 | 2018–2019 | Regular Session". LegiScan. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- ^ "New Jersey Legislature – Bills". www.njleg.state.nj.us. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- ^ a b "New Jersey Legislature – Bills". www.njleg.state.nj.us. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ^ "New Jersey Legislature – Bills". www.njleg.state.nj.us. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- ^ "Legislative Calendar". www.njleg.state.nj.us. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- ^ "New Jersey Legislature – Bills". www.njleg.state.nj.us. Retrieved 2019-03-15.

- ^ "New Jersey Legislature – Bills". www.njleg.state.nj.us. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- ^ "Vote for State Microbe | Department of Microbiology and Biochemistry at the Rutgers School of Environmental and Biological Sciences". dbm.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ^ "Rutgers Microbiology Symposium 2018" (PDF).

- ^ "NJ State Microbe Presentation at Rutgers Symposium". 19 February 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Seton Hall University to Host the Theobald Smith Society Meeting in Miniature – Seton Hall University". www.shu.edu. 11 April 2018. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- ^ "Program Planner". www.abstractsonline.com. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- ^ "Micro Minutes!, Microbiology at the NJ Historical Commission Forum..." Micro Minutes!. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- ^ "New Jersey Department of State – Historical Commission – Grants and Prizes". nj.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- ^ "Waksman Museum at Rutgers SEBS". waksmanmuseum.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- ^ "RECOGNIZING THE HISTORIC DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN MICROBIOLOGY AND IN PARTICULAR SOIL MICROBIOLOGY FROM GEORGE WASHINGTON TO SELMAN WAKSMAN – RUTGERS, THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW JERSEY". portal.nifa.usda.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- ^ "Eagleton Institute of Politics, Eagleton Science and Politic Workshop: Scientists in Politics Agenda" (PDF).

- ^ "Microbes Rule!". Liberty Science Center. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "Joined by friends and advocates, LSC announces support for official state microbe". Liberty Science Center. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- ^ "New Therapies Mean New Ways to Attack Infections". merck.com. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ CBS New York (2018-07-27), This Bacteria Could Become NJ's Official State Microbe, retrieved 2018-09-06

- ^ WarholScience (2018-08-03), News 12 NJ State Microbe, retrieved 2018-09-06

- ^ "N.J. Legislature Close To Giving Garden State An Official Microbe With Local Roots". NPR.org. Retrieved 2018-09-06.

- ^ Racaniello, Vincent. "Dr. Warhol's Periodic Table of Microbes – TWiM 181". Retrieved 2018-09-06.

- ^ "Seriously? New Jersey poised to name official state microbe". KYW. 2018-08-04. Retrieved 2018-09-06.

- ^ "Meet the bacteria that could become New Jersey's official state microbe". Asbury Park Press. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ a b Sheldon, Chris (27 July 2018). "Bacteria discovered in N.J. saved millions and could soon be our official state microbe". nj.com. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ Haydon, Ian (August 2018). "Move over, birds. New Jersey considers naming a 'state microbe.'". www.inquirer.com. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ Marcus, Samantha (2019-03-14). "Meet the life-saving microbe that's about to become N.J.'s newest state symbol". nj.com. Retrieved 2019-03-15.

- ^ Cutter, Joe (7 August 2018). "New Jersey's mighty microbe may finally get official recognition". New Jersey 101.5. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "Animal, Mineral, Vegetable, Microbe: Parsing NJ's Potential State Symbols – NJ Spotlight". www.njspotlight.com. 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ Cutter, Joe. "New Jersey's Mighty Microbe May Finally Get Official Recognition". WPG Talk Radio 95.5 Fm. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "Rutgers Discovery That Changed the World May Become New Jersey's State Microbe". Rutgers Today. 29 July 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "SENATE votes to strip MURPHY of certification power — ANTI-HUGIN ads funded by Texas billionaire — POOPERINTENDENT resigns". POLITICO. 27 July 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "This Bacteria Could Become NJ's Official State Microbe | Sarah the Web Girl | 102.3 WSUS". Sarah the Web Girl. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ a b "New Jersey could have an official life-saving microbe". Sky News. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "Rutgers professors nominate tuberculosis-curing bacteria for official state microbe". The Daily Targum. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- ^ "Home". njtvonline.org.

- ^ "Way To Go, Germs! New Jersey Considers a State Microbe". New Jersey Monthly. 2019-02-21. Retrieved 2019-03-15.

- ^ "People – Rebeca Ibarra | WNYC | New York Public Radio, Podcasts, Live Streaming Radio, News". WNYC. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "New Jersey Is Close to Having a State Microbe | WNYC | New York Public Radio, Podcasts, Live Streaming Radio, News". WNYC. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- ^ "Germ that led to TB treatment named New Jersey's state microbe". newjersey.news12.com. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- ^ "New Jersey gets official state microbe: Streptomyces griseus". The Seattle Times. 2019-05-10. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- ^ "U.S. News & World Report on NJ State Microbe".

- ^ "CUNY TV » City University Television". tv.cuny.edu. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "Meet The NJ Microbe! (as broadcast 7-10-2019)". Vimeo. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- ^ "Home". Jersey Matters. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ WJLP 'Jersey Matters' for MeTV3 (2019-06-17), Jersey Matters – State Microbe, retrieved 2019-07-19

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Choy, Isaac (25 January 2017). "HB1217". Hawaii State Legislature. Honolulu, HI: Hawaii State Legislature. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Taniguchi, Brian (25 January 2017). "SB1212". Hawaii State Legislature. Honolulu, HI: Hawaii State Legislature. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ "Illinois General Assembly – Bill Status for SB1857". www.ilga.gov. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ Luciano, Phil. "Luciano: A state microbe? Peoria to the rescue". Journal Star. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ "Illinois lawmakers could name official state soda, microbe". WQAD.com. 2019-03-18. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ "Education for Biodiversity Conservation CoP-11, Hyderabad". Press Information Bureau Government of India. Press Information Bureau Government of India Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. 18 October 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

The Minister also announced the National Microbe for India which was selected by children who had visited the Science Express Biodiversity Special, a train which has been visiting various stations across the country. Voting for the National Microbe took place in these stations and the children have selected the Lactobacillus (Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus) to be the National Microbe for India