Church of St Chad, Lichfield

| Church of St Chad, Lichfield | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| 52°41′22″N 1°49′15″W / 52.689373°N 1.820925°W | |

| Location | Lichfield, Staffordshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Website | The Church of St Chad |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade II* |

| Designated | 05.02.1952 |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Early English, Gothic |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Sandstone & Brick |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Lichfield |

| Parish | Lichfield |

| Clergy | |

| Rector | Reverend Chris Davies. |

| Curate(s) | Simon Foster |

| Laity | |

| Organist/Director of music | Anthony White |

| Churchwarden(s) | Caroline Fellows Kate Bowers |

| Parish administrator | Caroline Fellows |

The Church of St Chad is a parish church in the area of Stowe in the north of the city of Lichfield, Staffordshire, in the United Kingdom. It is a Grade II* Listed Building. The church is located to the north of Stowe Pool on St Chad's Road. The current building dates back to the 12th century although extensive restorations and additions have been made in the centuries since.

History

[edit]Chad came to Lichfield a few years before he became Bishop of Lichfield in 669 CE for the purpose of religious solitude. He settled in a wood and lived as a hermit in a cell by the side of a spring. From there he was known to preach and baptize his converts in the spring. It is believed that the location of Chad's cell and spring was in the current churchyard.

A monastery named the station of St Chad was built nearby the spring on the present site of the church around the time of St Chad. Of the original Saxon monastery nothing remains.[1]

During the 12th century the monastery was rebuilt as a church in stone and consisted of the nave, two side aisles and a chancel. The west door to the church stood where the tower now stands. The windows were set in gables and the lines of these gables and the rounded arches of the Norman windows in the south aisle are some of the oldest features still visible in today's building.[1]

During the 13th century the roof was replaced, the gables were dispensed with and the walls built up to the level of the window heads. The Norman windows were replaced with the Early English pointed windows seen today. The south arcade of five bays with octagonal pillars is also Early English, as are the chancel and the west doorway.[2]

The Tower on the west side was built in the 14th century to house the bells. The five-light chancel east window with cusped intersecting tracery was also built during this time as was the font, which is still in use today.[2]

The church was visited in 1323 by the Irish pilgrim Symon Semeonis on his way to the Holy Land. He described it as "a most beautiful church in honour of St. Chad, with most lofty stone towers, and splendidly adorned with pictures, sculptures, and other ecclesiastical ornaments."[3]

During the Reformation many of the church's assets were confiscated. During the English Civil War the church was occupied by Parliamentary troops who besieged the Close of Lichfield, the church was considerably damaged and the roof had to be rebuilt.[1] At this time the red brick clerestory was added and the single overall roof was replaced by three separate roofs, including a grained roof over the nave and panelled roof in the south aisle.[2]

Prominent as a curate in 1830–1837 was the eager high churchman William Gresley.

In 1840 the decision was taken to demolish the north aisle and rebuild it in a Victorian Gothic style. In 1862 the chancel and chancel arch were thoroughly restored and the brick clerestory extended over the chancel, a vestry was also added to the north side and the porch to the south. Further restoration work took place on the windows and the stained glass in the chancel. The east end of the south aisle seen today dates from that period.[1]

St Chad's Well

[edit]

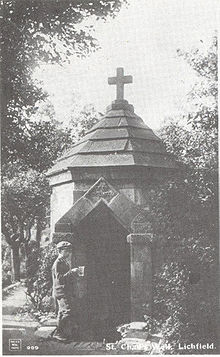

St Chad's Well is located in the churchyard to the north-west of the church. It was built over what was a sacred spring, where St Chad is reputed to have prayed on a stone at the spring, baptised his converts and healed peoples' ailments. It had become a popular place of pilgrimage by the 16th century.

In the 1830s James Rawson, a local physician, saw to it that the water supply was improved and an ornate octagonal stone structure erected over the well.[4] When the water dried up by the early 1920s, the well was lined with brick and a pump was fitted to the spring that fed it.[5] The stone structure was demolished in the 1950s and replaced with the simple timber structure and tiled canopy seen today.

The well is still a popular site of pilgrimage for Anglicans and Catholics, traditionally decorated with flowers and greenery at a well-dressing ceremony on Maundy Thursday. The vines currently covering the canopy are a traditional Christian symbol of the Eucharist wine.

Other features

[edit]Monuments

[edit]The monuments in the church include two in the south wall of the chancel with Johnsonian connections. One is to Lucy Porter (died 1786), Dr Johnson's stepdaughter. Below is a memorial to Catherine Chambers (died 1767), servant to Michael Johnson and his family. It was erected in 1910 after her tomb and that of Lucy Porter had been discovered during work on the chancel floor.[5]

A statue of St Chad was placed over the south porch in 1930 by Lady Blomefield in memory of her husband, Sir Thomas Blomefield of Windmill House (died 1928). In 1949 a screen was erected across the tower arch in memory of Alderman J. R. Deacon (died 1942) by his widow.[5]

The east end of the south aisle was formed into a Lady chapel in 1952 as a memorial to the fallen in the Second World War.[5]

Bells

[edit]St Chad's has four bells in its tower, three of which date from the 17th century and the fourth with an inscription dated 1255. At the Reformation, St Chad's was reported to have "three bells and a sanctus bell".[1]

Gallery

[edit]-

St Chad's Well as seen today with the wooden structure over it built in the 1950s

-

The trefoil-headed south door

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Simkin, D. J. (1983), A Guide to some Staffordshire Churches, Curlew Countryside Publications, ISBN 0-9506585-2-9

- ^ a b c Salter, Mike (1996), The Old Parish Churches of Staffordshire (2nd ed.), Folly Publications, p. 60, ISBN 1-871731-25-8

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Upton, Chris (2001), A History of Lichfield, Phillimore & Co Ltd, p. 10, ISBN 1-86077-193-9

- ^ a b c d Lichfield: Churches – British History Online, retrieved 5 August 2010