Der Judenstaat

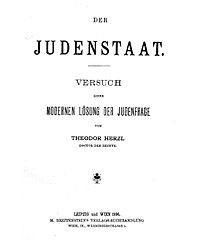

Title page of Der Judenstaat. 1896 | |

| Author | Theodor Herzl |

|---|---|

| Original title | Der Judenstaat |

| Language | German |

| Published | 14 February 1896 |

| Publication place | Austria-Hungary |

Original text | Der Judenstaat at German Wikisource |

| Translation | Der Judenstaat at Wikisource |

Der Judenstaat (German, lit. 'The State of the Jews',[1] commonly rendered[2][3] as The Jewish State) is a pamphlet written by Theodor Herzl and published in February 1896 in Leipzig and Vienna by M. Breitenstein's Verlags-Buchhandlung. It is subtitled with "Versuch einer modernen Lösung der Judenfrage" ("Proposal of a modern solution for the Jewish question") and was originally called "Address to the Rothschilds", referring to the Rothschild family banking dynasty,[4] as Herzl planned to deliver it as a speech to the Rothschild family. Baron Edmond de Rothschild rejected Herzl's plan, feeling that it threatened Jews in the Diaspora. He also thought it would put his own settlements in Palestine at risk.[5]

It is considered one of the most important texts of modern Zionism. As expressed in this book, Herzl envisioned the founding of a future independent Jewish state during the 20th century. He argued that the best way to avoid antisemitism in Europe was to create this independent Jewish state. The book encouraged Jews to purchase land in Palestine, the historic homeland of the Jews,[6] although the possibility of a Jewish state in Argentina is also considered as in that country's constitution Article 25 said that: the immigration of Europeans will be welcomed.

Herzl popularized the term "Zionism", which was coined by Nathan Birnbaum.[7] The nationalist movement culminated in the birth of the State of Israel in 1948, but Zionism continues to be connected with political support of Israel.

Summary

[edit]The book argues that after centuries of various restrictions, hostilities and frequent pogroms, the Jews of Europe had been reduced to living in ghettos. The higher class was forced to deal with angry mobs and so experienced a great deal of discomfort; the lower class lived in despair. Middle-class professionals were distrusted, and the statement "don't buy from Jews" caused much anxiety among Jewish people. It was reasonable to assume that the Jews would not be left in peace. Neither a change in the feelings of non-Jews nor a movement to merge into the surrounds of Europe offered much hope to the Jewish people:

"The Jewish question persists wherever Jews live in appreciable numbers. Wherever it does not exist, it is brought in together with Jewish immigrants. We are naturally drawn into those places where we are not persecuted, and our appearance there gives rise to persecution. This is the case, and will inevitably be so, everywhere, even in highly civilised countries—see, for instance, France—so long as the Jewish question is not solved on the political level."[8]

The book concludes:

Therefore I believe that a wondrous generation of Jews will spring into existence. The Maccabeans will rise again.

Let me repeat once more my opening words: The Jews who wish for a State will have it.

We shall live at last as free men on our own soil, and die peacefully in our own homes.

The world will be freed by our liberty, enriched by our wealth, magnified by our greatness.

And whatever we attempt there to accomplish for our own welfare, will react powerfully and beneficially for the good of humanity.[9]

Herzl proposed two possible regions for settlement – Argentina and Palestine – but recognized in Der Judenstaat that colonization in either would be difficult: "In both countries important experiments in colonization have been made, though on the mistaken principle of a gradual infiltration of Jews. An infiltration is bound to end badly. It continues till the inevitable moment when the native population feels itself threatened, and forces the government to stop a further influx of Jews. Immigration is consequently futile unless we have the sovereign right to continue such immigration."[10]

For that reason, Herzl, both in Der Judenstaat and in his political activity on behalf of Zionism, concentrated his efforts on securing official legal sanction from, as he put it, "the present masters of the land, putting itself under the protectorate of the European Powers, if they prove friendly to the plan." Attempts to negotiate with the Ottoman authorities failed, but with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I and the subsequent creation of Mandatory Palestine under the control of Britain, the Zionists gained success: Britain issued the Balfour Declaration that supported the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Outcome

[edit]As pointed out by Michael Stein, Herzl accurately predicted what would actually happen next: the influx of Jews into Mandatory Palestine in the 1930s did make the native Arab population feel threatened, leading to the 1936–1939 Arab revolt – which forced the British Government to announce in the White Paper of 1939 a stop to the further influx of Jews.[11]

The instrument envisioned by Herzl was "The Jewish Company" – "partly modeled on the lines of a great land-acquisition company. It might be called a Jewish Chartered Company" – i.e., following in the footsteps of the numerous Chartered Companies which had a major role in the outward expansion of various European powers since the 16th century. The Jewish Company envisioned by Herzl would have charge of both of the properties of all Jews in their present countries and of the lands and properties in the coming Jewish State; it would dispose of the former and provide every Jew with equivalent properties in the new land. Herzl clearly stipulated that "the Jewish Company will be founded as a joint stock company subject to English jurisdiction, framed according to English laws, and under the protection of England" – the City of London being at the time recognized as the financial capital of the world.

For the tasks envisioned for it, Herzl estimated that the company's capital should be about a thousand million marks (about £50,000,000 or $200,000,000). In fact, the Zionist Movement – both in Herzl's time and later – could not come anywhere close to such figures. Under Herzl's direction there was created a few years later the Jewish Colonial Trust – indeed located in London and incorporated under British law, but with the modest capital of 250,000 Pounds, about half of one percent of the envisioned Jewish Company. Even so, the "Colonial Trust" and its affiliate, the Anglo Palestine Company, had a key role in the actual implementation of the Zionist Project, and eventually became Bank Leumi, one of Israel's main banks.

References

[edit]- ^ Sachar, Howard (2007) [1976]. History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time (3 republication ed.). New York: Random House. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-375-71132-9.

- ^ Overberg, Henk (2012) [1997]. The Jews' State – A Critical English Translation (1 ed.). Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 3. ISBN 978-0765759733.

- ^ Hazony, Yoram. "Did Herzl Want A "Jewish" State? : Azure". Ideas for the Jewish Nation. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Herzl, Theodor (1988) [1896]. "Biography, by Alex Bein". Der Judenstaat [The Jewish state]. transl. Sylvie d'Avigdor (republication ed.). New York: Courier Dover. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-486-25849-2. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- ^ Pasachoff, Naomi (October 1992). Great Jewish Thinkers: Their Lives and Work. Behrman House. p. 97. ISBN 0874415292. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ Cleveland, William L. A History of the Modern Middle East. Boulder, CO: Westview, 2004. Print. p. 224

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Zionism". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Herzl, Der Judenstaat, cited by C.D. Smith, Israel and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 2001, 4th ed., p. 53

- ^ The Jewish State, by Theodor Herzl, (Courier Corporation, 27 Apr 2012), p. 157

- ^ Herzl, Theodor. The Jewish State. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Michael Stein, Collected Essays in the History of Zionism, Tel Aviv, 1954, pp. 46–47

Further reading

[edit]- Garrett, Leah (21 September 2012). "A Knight at the Opera: Heine, Wagner, Herzl, Peretz and the Legacy of Der Tannhäuser". Purdue University Press. Retrieved 8 October 2024.