Hakuin Ekaku

Hakuin Ekaku | |

|---|---|

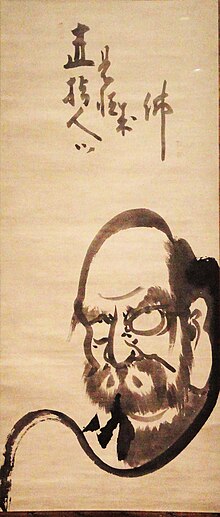

Hakuin Ekaku, self-portrait (1767) | |

| Title | Rōshi |

| Personal | |

| Born | c. 1686 |

| Died | c. 1769 |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Rinzai |

| Education | い |

| Part of a series on |

| Zen Buddhism |

|---|

|

Hakuin Ekaku (白隠 慧鶴, January 19, 1686 – January 18, 1769) was one of the most influential figures in Japanese Zen Buddhism, who regarded bodhicitta, working for the benefit of others, as the ultimate concern of Zen-training.[web 1] While never having received formal dharma transmission, he is regarded as the reviver of the Japanese Rinzai school from a period of stagnation, focusing on rigorous training methods integrating meditation and koan practice.

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Hakuin was born in 1686 in the small village of Hara,[web 2] at the foot of Mount Fuji. His mother was a devout Nichiren Buddhist, and it is likely that her piety was a major influence on his decision to become a Buddhist monk. As a child, Hakuin attended a lecture by a Nichiren monk on the topic of the Eight Hot Hells. This deeply impressed the young Hakuin, and he developed a pressing fear of hell, seeking a way to escape it. He eventually came to the conclusion that it would be necessary to become a monk.

Shōin-ji and Daishō-ji

[edit]At the age of fifteen, he obtained consent from his parents to join the monastic life, and was ordained at the local Zen temple, Shōin-ji, by the residing priest Tanrei Soden. Tanrei had a poor health, and Hakuin was soon sent to a neighboring temple, Daishō-ji, where he served as a novice for three or four years, studying Buddhist texts. While at Daisho-ji, he read the Lotus Sutra, considered by the Nichiren sect to be the king of all Buddhist sutras, and found it disappointing, saying "it consisted of nothing more than simple tales about cause and effect".

Zensō-ji

[edit]At age eighteen, he left Daishō-ji for Zensō-ji, a temple close to Hara.[1] At the age of nineteen, he came across in his studies the story of the Chinese Ch'an master Yantou Quanhuo, who had been brutally murdered by bandits. Hakuin despaired over this story, as it showed that even a great monk could not be saved from a bloody death in this life. How then could he, just a simple monk, hope to be saved from the tortures of hell in the next life? He gave up his goal of becoming an enlightened monk, and not wanting to return home in shame, traveled around studying literature and poetry.[2]

Zuiun-ji

[edit]Travelling with twelve other monks, Hakuin made his way to Zuiun-ji, the residence of Baō Rōjin, a respected scholar but also a tough-minded teacher.[3] While studying with the poet-monk Bao, he had an experience that put him back along the path of monasticism. He saw a number of books piled out in the temple courtyard, books from every school of Buddhism. Struck by the sight of all these volumes of literature, Hakuin prayed to the gods of the Dharma to help him choose a path. He then reached out and took a book; it was a collection of Zen stories from the Ming Dynasty. Inspired by this, he repented and dedicated himself to the practice of Zen.[4]

First awakening

[edit]Eigen-ji

[edit]He again went traveling for two years, settling down at the Eigen-ji temple when he was twenty-three. It was here that Hakuin had his first entrance into enlightenment when he was twenty-four.[5] He locked himself away in a shrine in the temple for seven days, and eventually reached an intense awakening upon hearing the ringing of the temple bell. However, his master refused to acknowledge this enlightenment, and Hakuin left the temple.

Shōju Rōjin

[edit]Hakuin left again, to study for a mere eight months with Shōju Rōjin (Dokyu Etan, 1642–1721),[6] an enigmatic teacher whose historicity has been questioned.[7] According to Hakuin and his biographers, Shoju was an intensely demanding teacher, who hurled insults and blows at Hakuin, in an attempt to free him from his limited understanding and self-centeredness. When asked why he had become a monk, Hakuin said that it was out of terror to fall into hell, to which Shōju replied "You're a self-centered rascal, aren't you!"[8] Shōju assigned him a series of "hard-to-pass" koans. These led to three isolated moments of satori, but it was only eighteen years later that Hakuin really understood what Shōju meant with this.[8]

Hakuin left Shoju after eight months of study,[9] but in later life, when he had realized Shoju's teachings on the importance of bodhicitta, Hakuin considered Shoju Rojin his primary teacher, and solidly identified himself with Shoju's dharma-lineage. Today Hakuin is considered to have received dharma transmission from Shoju,[web 3] though he didn't receive formal dharma transmission from Shoju Rojin,[10] nor from any other teacher,[web 4] a contradiction for the Rinzai's school emphasis on formal dharma-transmission.[11]

Incomplete accomplishment and renewed doubt

[edit]Hakuin realized that his attainment was incomplete.[12] His insight was sharp during meditation,[13] but he was unable to sustain the tranquility of mind of the Zen hall in the midst of daily life.[12] His mental dispositions were unchanged, and attachment and aversion still prevailed in daily life, a tendency which he could not correct through "ordinary intellectual means."[13][note 1] His mental anguish even worsened when, at twenty-six, he read that "all wise men and eminent priests who lack the Bodhi-mind fall into Hell".[17] This raised a "great doubt" (taigi) in him, since he thought that the formal entrance into monkhood and the daily enactment of rituals was the bodhi-mind.[17] Only with his final awakening, at age 42, did he fully realize what "bodhi-mind" means, namely working for the good of others.[17]

Zen sickness

[edit]Hakuin's early extreme exertions affected his health, and at one point in his young life he fell ill for almost two years, experiencing what would now probably be classified as a nervous breakdown by Western medicine. He called it Zen sickness, and in later life often narrated[note 2] to have sought the advice of a Taoist cave dwelling hermit named Hakuyu, who prescribed a visualization (the 'soft butter method') and breathing practice ('introspective meditation', using abdominal breathing and focussing on the hara), which eventually relieved his symptoms. From this point on, Hakuin put a great deal of importance on physical strength and health in his Zen practice, and studying Hakuin-style Zen required a great deal of stamina. Hakuin often spoke of strengthening the body by concentrating the spirit, and followed this advice himself. Well into his seventies, he claimed to have more physical strength than he had at age thirty, being able to sit in zazen meditation or chant sutras for an entire day without fatigue. The practices Hakuin claimed to have learned from Hakuyu are still passed down within the Rinzai school.[18]

Temple priest at Shōin-ji

[edit]After another several years of travel, at age 31 Hakuin returned to Shoin-ji, the temple where he had been ordained. He was soon installed as head priest, a capacity in which he would serve for the next half-century, giving Torin Sosho, who had followed-up Tanrei, as his "master" when enscribing himself in the Mioshi-ji bureaucracy.[19][20] When he was installed as head priest of Shōin-ji in 1718, he had the title of Dai-ichiza, "First Monk":[21]

It was the minimum rank required by government regulation for those installed as temple priests and seems to have been little more than a matter of paying a fee and registering Hakuin as the incumbent of Shōin-ji.[21]

It was around this time that he adopted the name "Hakuin", which means "concealed in white", referring to the state of being hidden in the clouds and snow of mount Fuji.[22]

Final awakening

[edit]Although Hakuin had several "satori experiences", he did not feel free, and was unable to integrate his realization into his ordinary life.[23] While eventually admitting a small number of students, Hakuin committed himself to a thorough practice, sitting all night in zazen. At age 41, he experienced a decisive awakening, while reading the Lotus Sutra, the sutra that he had disregarded as a young student. He realized that the Bodhi-mind means working for the good of every sentient being:[24]

It was the chapter on parables, where the Buddha cautions his disciple Shariputra against savoring the joys of personal enlightenment, and reveals to him the truth of the Bodhisattva's mission, which is to continue practice beyond enlightenment, teaching and helping others until all beings have attained salvation.[23]

He wrote of this experience, saying "suddenly I penetrated to the perfect, true, ultimate meaning of the Lotus". This event marked a turning point in Hakuin's life. He dedicated the rest of his life to helping others achieve liberation.[23][24]

Practicing the bodhi-mind

[edit]

He would spend the next forty years teaching at Shoin-ji, writing, and giving lectures. At first there were only a few monks there, but soon word spread, and Zen students began to come from all over the country to study with Hakuin. Eventually, an entire community of monks had built up in Hara and the surrounding areas, and Hakuin's students numbered in the hundreds. He eventually would certify over eighty disciples as successors.

Is that so?

[edit]A well-known anecdote took place in this period:

A beautiful Japanese girl whose parents owned a food store lived near Hakuin. One day, without any warning, her parents discovered she was pregnant. This made her parents angry. She would not confess who the man was, but after much harassment at last named Hakuin.

In great anger the parents went to the master. "Is that so?" was all he would say. After the child was born it was brought to Hakuin. By this time he had lost his reputation, which did not trouble him, but he took very good care of the child. He obtained milk from his neighbors and everything else the child needed by takuhatsu.[note 3]

A year later the girl could stand it no longer. She told her parents the truth – the real father of the child was a young man who worked in the fish market.

The mother and father of the girl at once went to Hakuin to ask forgiveness, to apologize at length, and to get the child back.

Hakuin smiled and willingly yielded the child, saying: "Is that so? It's good to hear this baby has his/her father."[26]

Death

[edit]Shortly before his death, Hakuin wrote

An elderly monk of eighty-four, I welcome in yet one more year

And I owe it all – everything – to the Sound of One Hand barrier.[27]

Written over a large calligraphic character 死 shi, meaning Death, he had written as his jisei (death poem):

若い衆や死ぬがいやなら今死にやれ

一たび死ねばもう死なぬぞや

Wakaishu ya

shinu ga iya nara

ima shiniyare

hito-tabi shineba

mō shinanu zo ya

Oh young folk –

if you fear death,

die now!

Having died once

you won't die again.[28]: 6

At the age of 83, Hakuin died in Hara, the same village in which he was born and which he had transformed into a center of Zen teaching.

Teachings

[edit]

Like his predecessors Shidō Bu'nan (Munan) (1603–1676) and Dōkyō Etan (Shoju Rojin, "The Old Man of Shōju Hermitage") (1642–1721), Hakuin stressed the importance of kensho and post-satori practice, deepening one's understanding and working for the benefit of others. Just like them he was critical of the state of practice in the Rinzai-establishment, which he saw as lacking in rigorous training.

Post-satori practice

[edit]Hakuin saw "deep compassion and commitment to help all sentient beings everywhere"[29] as an indispensable part of the Buddhist path to awakening. Hakuin emphasized the need for "post-satori training",[30][31] purifying the mind of karmic tendencies and

[W]hipping forward the wheel of the Four Universal Vows, pledging yourself to benefit and save all sentient beings while striving every minute of your life to practice the great Dharma giving.[31]

The insight in the need of arousing bodhicitta formed Hakuin's final awakening:

What is to be valued above all else is the practice that comes after satori is achieved. What is that practice? It is the practice that puts the Mind of Enlightenment first and foremost.

[At] my forty-first year, [...] I at long last penetrated into the heart of this great matter. Suddenly, unexpectedly, I saw it — it was as clear as if it were right there in the hollow of my hand. What is the Mind of Enlightenment? It is, I realized, a matter of doing good — benefiting others by giving them the gift of the Dharma teaching.[31]

Koan practice

[edit]Koan-training

[edit]Hakuin deeply believed that the most effective way for a student to achieve insight was through extensive meditation on a koan. Only with incessant investigation of his koan will a student be able to become one with the koan, and attain enlightenment. The psychological pressure and doubt that comes when one struggles with a koan is meant to create tension that leads to awakening. Hakuin called this the "great doubt", writing, "At the bottom of great doubt lies great awakening. If you doubt fully, you will awaken fully".[32]

Hakuin used two or three stages in his application of koan-training. Students had to develop their ability to see (kensho) their true nature. Yet, they also had to sustain the "great doubt", going beyond their initial awakening and further deepen their insight struggling with "difficult-to-pass" (nanto) koans, which Hakuin seems to have inherited from his teachers. This further training and awakening culminates in a full integration of understanding and quietude with the action of daily life, and bodhicitta, upholding the four bodhisattva-vows and striving to liberate all living beings.[33]

Hear the sound of one hand

[edit]In later life he used the instruction "Hear the sound of one hand," which actually consists of two parts, to raise the great doubt with beginners. He first mentioned it when writing

By Kannon Bosatsu is meant the contemplation of sounds, and that is what I mean by [hearing] the sound of the single hand.[note 4]

Kannon Bosatsu is Kanzeon (Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin), the bodhisattva of great compassion, who hears the sounds of all people suffering in this world. The second part is "Put a stop all sounds,"[34][35] referring to the first bodhisattva vow of liberating all sentient beings.[note 5]

Hakuin preferred this to the most commonly assigned first koan from the Chinese tradition, the Mu koan. He believed his "Sound of One Hand" to be more effective in generating the great doubt, and remarked that "its superiority to the former methods is like the difference between cloud and mud".[40]

While 'the sound of one hand' is the classical instruction used by Hakuin, in Hakuin on kensho and other writings he emphasises the Hua Tou-like question "Who is the host of seeing and hearing?"[41] to arouse the great doubt,[note 6] akin to Bassui Tokushō's (1327–1387) "Who is hearing this sound?", and the Ōbaku use of the "nembutsu kōan", which entailed the practice of reciting the name of Amitabha while holding in one's mind the kōan, "Who is reciting?"[42] Bassui equates Buddha-nature or the One Mind with Kanzeon, compassion.[43] "...someone who, for every sound he heard, contemplated the mind of the hearer, thereby realizing his true nature."[44] Bassui further explains that "The one gate – the so-called one who hears the Dharma [...] – was the perfection achieved by the bodhisattva Kannon."[45][note 7]

As for antecedents of 'the sound of one hand', it "has a close relation to,"[47] or is "adapted from,"[48] Xuedou Chongxian's (980-1052) poetic commentary that "a single hand by itself produces no sound," which appears in case 18 of The Blue Cliff Record.[49][50] One hand also appears in some interactions and explanations. When first meeting Shōju Rōjin, Hakuin

boasted of the "depth" and "clarity" of his own Zen understanding in the form of an elegant verse put down on a sheet of paper. Dokyo, crushing the paper with his left hand, held out his right hand and said, "Putting learning aside, what have you seen?"[51]

The "Recorded Sayings" of Zhaozhou Congshen (Jōshū Jūshin, 778–897) contain the following episode:

There was a priest from Ting-chou (Joshu) who came to visit. The master asked him, "What practice do you undertake?"

The priest said, "Without listening to scriptures, commandments, or discourses, I understand them."

The master raised his hand and pointed to it saying "Well, do you understand that?"[52]

Regarding his final awakening, in his biography Wild Ivy Hakuin wrote

“Of all the sages and holy monks since the time of the Buddha Krakucchanda, those lacking bodhicitta have all fallen into the realm of the demons.” For long I wondered what these words meant.... I pondered them from the age of twenty-five, and it was not until I reached forty-two that I unexpectedly perceived their meaning, as clearly as though they were in the palm of my hand. What is bodhicitta? It is the good practices of preaching the Dharma and benefiting others.[web 1][53]

Four ways of knowing

[edit]Asanga, one of the main proponents of Yogacara, introduced the idea of four ways of knowing: the perfection of action, observing knowing, universal knowing, and great mirror knowing. He relates these to the Eight Consciousnesses:

- The five senses are connected to the perfection of action,

- Samjna (cognition) is connected to observing knowing,

- Manas (mind) is related to universal knowing,

- Alaya-vijnana is connected to great mirror knowing.[54]

In time, these ways of knowing were also connected to the doctrine of the three bodies of the Buddha (Dharmakāya, Sambhogakāya and Nirmanakaya), together forming the "Yuishiki doctrine".[54]

Hakuin related these four ways of knowing to four gates on the Buddhist path: the Gate of Inspiration, the Gate of Practice, the Gate of Awakening, and the Gate of Nirvana.[55]

- The Gate of Inspiration is initial awakening, kensho, seeing into one's true nature.

- The Gate of Practice is the purification of oneself by continuous practice.

- The Gate of Awakening is the study of the ancient masters and the Buddhist sutras, to deepen the insight into the Buddhist teachings, and acquire the skills needed to help other sentient beings on the Buddhist path to awakening.

- The Gate of Nirvana is the "ultimate liberation", "knowing without any kind of defilement".[55]

The Five Ranks

[edit]Hakuin found the study and understanding of Dongshan Liangjie's (Jp. Tōzan Ryōkan) Five Ranks highly useful in post-satori practice.[56] Today, they form part of the 5th step of the Japanese Rinzai koan-curriculum.

Opposition to "Do-nothing Zen"

[edit]One of Hakuin's major concerns was the danger of what he called "Do-nothing Zen" teachers, who upon reaching some small experience of enlightenment devoted the rest of their life to, as he puts it, "passing day after day in a state of seated sleep".[57] Quietist practices seeking simply to empty the mind, or teachers who taught that a tranquil "emptiness" was enlightenment, were Hakuin's constant targets. In this regard he was especially critical of followers of the maverick Zen master Bankei.[58] He stressed a never-ending and severe training to deepen the insight of satori and forge one's ability to manifest it in all activities.[30][31] He urged his students to never be satisfied with shallow attainments, and truly believed that enlightenment was possible for anyone if they exerted themselves and approached their practice with real energy.[31]

Zen-sickness and vital energy

[edit]In several of his writings,[note 8] most notably Yasenkanna ("Idle Talk on a Night Boat")[note 9] Hakuin describes how he cured his Zen-sickness (zenbyō) by using two methods explained to him by Hakuyū, a Taoist cave-dwelling hermit. These methods are 'introspective meditation', a contemplation practice called naikan[62][note 10] using abdominal breathing and focussing on the hara, and a visualization, the 'soft butter method'.[18]

According to Katō Shǒshun, this zen-sickness most likely happened when Hakuin was in his late twenties. Shǒshun conjects that these remedies were worked out by Hakuin on his own, from "a combination of traditional medical and meditation texts and folk therapies current at the time."[64] According to Waddell, Yasenkanna has been in print ever since it was published, reflecting its popularity in secular circles.[60]

In the preface to Yasenkanna, attributed by Hakuin to a disciple called "Hunger and Cold, the Master of Poverty Hermitage," Hakuin explains that a long life can be attained by disciplining the body through gathering the ki, the life-force or "the fire or heat in your mind (heart)," in the tanden or lower belly, producing "the true elixir" (shintan), which is "not something located apart from the self."[65] He describes a four-step contemplation to concentrate the ki in the tanden, as a cure against zen-sickness.[66] In the naikan method, as explained by "the master," the practitioner lays down on his back, and concentrates the ki in the tanden, using the following contemplations:[67]

1. This tanden of mine in the ocean of ki – the lower back and legs, the arches of the feet – is nothing other than my true and original face. How can that original face have nostrils?

2. This tanden of mine in the ocean of ki – the lower back and legs, the arches of the feet – is all the home and native place of my original being. What tidings could come from that native place?

3. This tanden of mine in the ocean of ki – the lower back and legs, the arches of the feet – is all the Pure Land of my own mind. How could the splendors of that Pure Land exist apart from my mind?

4. This tanden of mine in the ocean of ki is all the Amida Buddha of my own self. How could Amid Buddha preach the Dharma apart from that self?

This method is different from the 'soft butter' method, and, according to Waddell, closer to traditional Zen-practice.[66] Hakuin himself warns that longevity is not the goal of Buddhism, and is incomparable to following the Bodhisattva vows, "constantly working to impart the great Dharma to others as you acquire the imposing comportment of the Bodhisattva."[68]

In the main text of the Yasenkanna Hakuin lets Hakuyū give an extensive explanation on the principles of Chinese medicine[69] and the dictum of "bringing the heart down into your lower body,"[70] without giving concrete instructions for practice. Hakuin has Hakuyū further explain that "false meditation is meditation that is diverse and unfocused," while "true meditation is no-meditation."[70][note 11] Hakuyū then comes with a series of quotations and references from Buddhist sources.[71] In passing, Hakuyū refers to "a method in the Agama[note 12] in which butter is used."[72] On Hakuin's request, Hakuyū then sets out to explain the 'butter method'. In this method, one visualizes a lump of soft butter on the head, which slowly melts, relaxing the body as it spreads over all parts of it.[73]

Influence

[edit]Emphasis on kensho and post-satori practice

[edit]Hakuin put a strong emphasis on kensho and post-satori practice, following the examples of his dharma-predecessors Gudō Toshoku (1577–1661), Shidō Bu'nan (Munan)(1603–1676), and his own teacher Shoju Rojin (Dokyu Etan), 1642–1721).[74] The emphasis on kensho had a strong influence on western perceptions of Zen through the writings of D.T. Suzuki and the practice-style of Yasutani, the founder of the Sanbo Kyodan, though the Sanbo Kyodan has also incorporated the necessity of post-satori practice.

Revival of Rinzai and Otokan

[edit]Hakuin is generally considered as the reviver of the Japanese Rinzai-tradition from a long period of stagnation and decline of monastic rigor.[75] Yet, Ahn notes that this also a matter of perception, and that multiple factors are at play here.[76] In Hakuin's time, support from the upper classes for the Zen-institutions had waned, and Zen-temples had to secure other means of support, finding it in a lay-audience.[77] There was also the challenge of the Chinese Ōbaku-school, with its emphasis on rigorous communal training and more accessible teachings.[77] Heine and Wright note that:[78]

... regardless of its inclusion of Pure Land elements, the fact remained that the Ōbaku school, with its group practice of zazen on the platforms in a meditation hall and its emphasis on keeping the precepts, represented a type of communal monastic discipline far more rigorous than anything that existed at the time in Japanese Buddhism.

As a result of their approach, which caused a stir in Japan, many Rinzai and Sōtō masters undertook reforming and revitalizing their own monastic institutions, partly incorporating Ōbaku, partly rejecting them. Kogetsu Zenzai welcomed their influence, and Rinzai master Ungo Kiyō even began implementing the use of nembutsu into his training regimen at Zuigan-ji.[78] Other teachers, not only Hakuin, responded to these challenges by harking back to the roots of their own school, and by adapting their style of teaching.[79] Hakuin was affiliated to Myōshin-ji and the Ōtōkan lineage,[79] and sought to restore what he considered as the authentic, China-derived and koan-oriented Zen-practice of the Otokan-lineage and its founders, Dai'ō Kokushi (Nanpo Shōmyō (1235–1308), who received dharma-transmission in China from Xutang Zhiyu; Daitō Kokushi (Shuho Myocho) (1283-1338); and Kanzan Egen (1277–1360). While the communal training of the Ōbaku-school was emulated,

The followers of Hakuin Ekaku (1687—1769) tried to purge the elements of Ōbaku Zen they found objectionable. They suppressed the Pure Land practice of reciting Amida Buddha's name, deemphasized the Vinaya, and replaced sutra study with a more narrow focus on traditional koan collections.[80]

Hakuin's outreach to a lay-audience fits into these Japanese responses to these challenges.[79] The ringe-monasteries Myoshin-ji and Daitoku-ji, belonging to the Otokan-lineage, rose to prominence in these new circumstances.[79]

Lineage

[edit]Hakuin took ordination in a Mioshi-ji affiliated temple, and remained loyal to this institution and its lineage throughout his life. In 1718, when he was installed as head priest, Hakuin noted Torin Sosho as his "master," but after his awakening to the importance of karuna and understanding Shōju Rōjin's stress on sustained post-satori practice, Hakuin regarded Shōju Rōjin as his principal teacher, though he never received formal dharma transmission from him.[81] Little is known of Shōju Rōjin, and his historicity has even been questioned, yet confirmed by Nakamura.[10] While traced back to the Otokan-lineage, Shōju Rōjin's fell into obscurity in the 16th century, and little is known of the 16th-century teachers.

Hakuin's closest student and companion was Tōrei Enji (1721-1792), who first studied with Kogetsu Zenzai, and to whom Hakuin presented his robe as a token of recognition.[82]

All contemporary Rinzai-lineages are related to Hakuin through Gasan Jitō (1727–1797) and his students Inzan Ien (1751–1814) and Takuju Kosen (1760–1833).[83][84] Gasan received Dharma transmission from Rinzai teacher Gessen Zen'e, who had received dharma transmission from Kogetsu Zenzai, before meeting Hakuin.[85] While Gasan is considered to be a dharma heir of Hakuin, "he did not belong to the close circle of disciples and was probably not even one of Hakuin's dharma heirs,"[86] studying with Hakuin but completing his koan-training with Tōrei Enji.[82]

| Linji lineage / Linji school | |||

| Xuan Huaichang |

Xutang Zhiyu 虚堂智愚 (Japanese Kido Chigu, 1185–1269) [web 6] [web 7] [web 8] | ||

| Eisai (1141-1215) (first to bring Linji school to Japan) |

Nanpo Shōmyō (南浦紹明?), aka Entsū Daiō Kokushi (1235–1308) (brought Ōtōkan school to Japan) | ||

| Myozen | Shuho Myocho, aka Daitō Kokushi, founder of Daitoku-ji | ||

| Kanzan Egen 關山慧玄 (1277–1360) founder of Myōshin-ji |

| ||

| Juō Sōhitsu (1296–1380) | |||

| Muin Sōin (1326–1410) | |||

| Tozen Soshin (Sekko Soshin) (1408–1486) | |||

| Toyo Eicho (1429–1504) | |||

| Taiga Tankyo (?–1518) | |||

| Koho Genkun (?–1524) | |||

| Sensho Zuisho (?–?) | |||

| Ian Chisatsu (1514–1587) | |||

| Tozen Soshin (1532–1602) | |||

| Yozan Keiyō (?–?) | |||

| Gudō Toshoku (1577–1661) | |||

| Shidō Bu'nan (Munan)(1603–1676) | |||

| Shoju Rojin (Shoju Ronin, Dokyu Etan, 1642–1721) | Kengan Zen'etsu | ||

| Hakuin (1686–1768) | Kogetsu Zenzai | ||

| Tōrei Enji (1721-1792) ("principle Dharma heir" of Hakuin[87]) |

Gessen Zen'e | ||

| # Gasan Jitō 峨山慈棹 (1727–1797) (received dharma trasmission from Gessen Zen'e; studied with Hakuin, received inka from Tōrei Enji[88]) | |||

| Inzan Ien 隱山惟琰 (1751–1814) | Takujū Kosen 卓洲胡僊 (1760–1833) | ||

| Inzan lineage | Takujū lineage | ||

| View template | |||

Lay teachings

[edit]An extremely well known and popular Zen master during his later life, Hakuin was a firm believer in bringing liberation to all people. Thanks to his upbringing as a commoner and his many travels around the country, he was able to relate to the rural population, and served as a sort of spiritual father to the people in the areas surrounding Shoin-ji. In fact, he turned down offers to serve in the great monasteries in Kyoto, preferring to stay at Shoin-ji. Most of his instruction to the common people focused on living a morally virtuous life. Showing a surprising broad-mindedness, his ethical teachings drew on elements from Confucianism, ancient Japanese traditions, and traditional Buddhist teachings. He also never sought to stop the rural population from observing non-Zen traditions, despite the seeming intolerance for other schools' practices in his writings.

Lecturing tours and writing

[edit]In later life Hakuin was a popular Zen lecturer, traveling all over the country, often to Kyoto, to teach and speak on Zen. He wrote frequently in the last fifteen years of his life, trying to record his lessons and experiences for posterity. Much of his writing was in the vernacular, and in popular forms of poetry that commoners would read.

Calligraphy

[edit]An important element of Hakuin's Zen-teaching and pedagogy was his painting and calligraphy. He seriously took up painting only late in his life, at almost age sixty, but is recognized as one of the greatest Japanese Zen painters. His paintings were meant to capture Zen values, serving as sorts of "visual sermons" that were extremely popular among the laypeople of the time, many of whom were illiterate. Today, paintings of Bodhi Dharma by Hakuin Ekaku are sought after and displayed in a handful of the world's leading museums.

Systematisation of koan-practice

[edit]Hakuin's emphasis on koan practice had a strong influence in the Japanese Rinzai-school. In the system developed by his followers, students are assigned koans in a set sequence by their teacher and then meditate on them. Once they have broken through, they must demonstrate their insight in private interview with the teacher. If the teacher feels the student has handled the koan in a satisfactory way, then they receive the standard answer, and the next koan in the sequence is assigned.

Gasan Jitō (1727–1797), who received dharma transmission from Hakuin's heir

Tōrei Enji (1721-1792), and Gasan's students Inzan Ien (1751–1814) and Takuju Kosen (1760–1833) developed a fivefold classification system:[89]

1. Hosshin, dharma-body koans, are used to awaken the first insight into sunyata.[89] They reveal the dharmakaya, or Fundamental.[90] They introduce "the undifferentiated and the unconditional".[91]

2. Kikan, dynamic action koans, help to understand the phenomenal world as seen from the awakened point of view;[92] Where hosshin koans represent tai, substance, kikan koans represent yu, function.[93]

3. Gonsen, explication of word koans, aid to the understanding of the recorded sayings of the old masters.[94] They show how the Fundamental, though not depending on words, is nevertheless expressed in words, without getting stuck to words.[clarification needed][95]

4. Hachi Nanto, eight "difficult to pass" koans.[96] There are various explanations for this category, one being that these koans cut off clinging to the previous attainment. They create another Great Doubt, which shatters the self attained through satori. [97] It is uncertain which are exactly those eight koans.[98] Hori gives various sources, which altogether give ten hachi nanto koans.[99]

5. Goi jujukin koans, the Five Ranks of Tozan and the Ten Grave Precepts.[100][96]

Hakuin's main role in the development of this koan system was most likely the example and inspiration he set with his own determination an vigour for koan. The standardisation of collective zazen-practice, introducing scheduled sesshin at Mioshi-ji and its affiliated temples in the 18th century, may be an important institutional factor, requiring standardised practice-tools.[101]

Writings

[edit]Hakuin left a voluminous body of works, divided in Dharma Works (14 vols.) and Kanbun Works (4 vols.).[102] The following are the best known, and also translated in English:

- Orategama (遠羅天釜), The Embossed Tea Kettle, a letter collection.

- Yasen kanna (夜船閑話), Idle Talk on a Night Boat, a work on health-improving meditation techniques (qigong).

Relevant and instructive is also:

- Hakuin, Ekaku (2010), Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, Norman Waddell, translator, Shambhala Publications, ISBN 9781570627705

His explanation of the Five Ranks appears in:

- Hakuin (2005), The Five Ranks. In: Classics of Buddhism and Zen. The Collected Translations of Thomas Cleary, vol. 3, Boston, MA: Shambhala, pp. 297–305

See also

[edit]- Buddhism in Japan

- List of Rinzai Buddhists

- List of Buddhist topics

- Religions of Japan

- Zazen Wasan, a wasan composed by Hakuin Ekaku

Notes

[edit]- ^ Compare remarks and experiences by contemporary teachers, e.g. Jack Kornfield,[14]Taizan Maezumi,[15] Barry Magid,[16] that insight attained through practice did not alter their mental predispositions and problems.

- ^ See:

- Yasenkanna ("Idle Talk on a Night Boat"), in: Hakuin's Precioyus Mirror Cave, Waddell 2009

- Itsumadegusa ("Wild Ivy"), Hakuin 2010

- ^ Takuhatsu (托鉢) is a traditional form of dāna or alms given to Buddhist monks in Japan.[25]

- ^ Shore 1996, p. 33 referring to Tokiwa 1991; Tokiwa in turn quotes from Hakuin's Neboke no Mezame.

- ^ Compare the Blue Cliff Record case 89, "Hands and Eyes All Over"[36] (or "The Hands and Eyes of the Bodhisattva of Great Compassion"[37]); idem Book of Serenity Case 54; Dogen's Mana Shobogenzo ("Dogen's 300 koans") Case 105, also in Dogen's Kana Shobogenzo, chapters Daishugyo and Kannon:[38]

Ungan asked Dogo, “What does the bodhisattva of great compassion use so many hands and eyes for?”

Dogo said, “Like someone reaching back for a pillow in the middle of the night.”

Ungan said, “I understand.”

Dogo said, “How do you understand?”

Ungan said, “All over the body are hands and eyes.”

Dogo said, “You’ve said quite a bit, but you’ve only expressed eighty percent.”

Ungan said, “What about you?”

Dogo said, “Throughout the body are hands and eyes.”

Hakuin comments: "Throughout the body are hands and eyes—The elbow doesn’t bend outward";[36] a Japanese expression, meaning that it is natural, things are as they are. Compare the fifth of the Five Ranks, Unity Attained, which completes Hakuin's understanding of the course of Zen-training, referring to the "mellow maturity of consciousness."[39] The expression is also used by D.T Suzuki, see here and here.

See also the many commentaries to be found at the internet for "reaching back for a pillow in the middle of the night,” and the following comment by Zarrilli about Kalaripayattu, a amrtial art from Kerala, South-India:

"In Kerala, there is a folk expression which summarizes the martial practitioner's ideal state of psychophysiologicaVpneumatic accomplishment explored here--a state in which the "body becomes all eyes" (meyyu kannakuka). One reading of the "body as all eyes" is as the yogic/Ayurvedic bodymind, which intuitively responds to the sensory environment and which is healthful and fluid in its congruency. It is the animal body in which there is unmediated, uncensored, immediate respondence to stimuli. Like Brahma, the "thousand eyed," the practitioner who is accomplished can "see" everywhere around him, intuitively sensing danger in the environment and responding immediately." - ^ Hakuin: "Constantly, he proceeds, asking, "What is this thing, what is this thing? Who am I?" This is called the way of "the lion that bites the man.""[web 5]

- ^ The same question, "Who is it?", is also explicated by Torei in The Undying Lamp of Zen, and recommended by Ramana Maharshi with his emphasis on self-enquiry, and by Nisargadatta Maharaj.[46]

- ^ First Kanzan-shi Sendai-kimon (1746),[59]

- ^ Translated in Hakuin's Precious Mirror CaveWaddell 2009 (1757)[60] and "used almost verbatim as the fourth chapter of"[61] Itsumadegusa ("Wild Ivy"),[31]Hakuin's autobiography.

- ^ Waddell notes that Hakuin used the term naikan to refer to meditation methods to concentrate ki in the lower belly, but also for more traditional meditation methods, such as koan-practice.[63]

- ^ Waddell 2009, p. 266, note 78 explains that "diverse meditation" (takan) presumably refers to "unfocused meditation on koans in which the meditation topic becomes the object of discrimination and ki does not gather in the lower body," while "no-meditation" (mukan) is similar to mumen ("no-thought") or mushin ("no-mind"). Both refer to observing the mind.

- ^ The early Buddhist sutras preserved in Chinese translation, akin to the Sutta Piṭaka

References

[edit]- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xv.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xvi.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xvii.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xviii–xix.

- ^ Waddell 2010b, p. xvii.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xxi–xxii.

- ^ Mohr (2003), p. 311.

- ^ a b Waddell 2010a, p. xxii.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xxii–xxiii.

- ^ a b Mohr 2003, p. 311-312.

- ^ Haskel (2022).

- ^ a b Waddell 2010a, p. xxv.

- ^ a b Torei (2009), p. 175.

- ^ Jack Kornfield, A Path With a Heart

- ^ Steve Silberman (2021), Roshi, You Are Drunk, Lion's Roar

- ^ Magid, B (2013). Nothing is Hidden: The Psychology of Zen Koans. Wisdom

- ^ a b c Yoshizawa 2009, p. 44.

- ^ a b Waddell 2002.

- ^ Mohr 2003, p. 212.

- ^ Haskel (2022), p. 108.

- ^ a b Waddell 2010a, p. xxix.

- ^ Stevens 1999, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Waddell 2010b, p. xviii.

- ^ a b Yoshizawa 2009, p. 41.

- ^ "Takuhatsu". A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 9780198605607.

- ^ Reps & Senzaki 2008, p. 22; Kimihiko 1975.

- ^ Haskel (2022), p. 113.

- ^ Hoffmann, Yoel (1986). Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death. Rutland, VT: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN 978-0804831796.

- ^ Low 2006, p. 35.

- ^ a b Waddell 2010a.

- ^ a b c d e f Hakuin 2010.

- ^ McEvilley, Thomas (August 1999). Sculpture in the age of doubt. New York: Allworth Press. ISBN 9781581150230. OCLC 40980460.

- ^ Ahn (2019), p. 518-520.

- ^ Waddell (2009), p. 4.

- ^ Haskel (2022), p. 110.

- ^ a b Cleary 2002, p. 309.

- ^ Cleary & Cleary 2005, p. 489.

- ^ Loori (2006), p. 157.

- ^ Sekida 1996, p. 57.

- ^ Hakuin 2010, p. xxxvi.

- ^ Hakuin (2006), p. 31.

- ^ Heine & Wright (2005), p. 151.

- ^ Bassui (2002), p. 104, 108.

- ^ Bassui (2002), p. 113.

- ^ Bassui (2002), p. 160.

- ^ Low (2006), p. 72-73.

- ^ Sekida (1996), p. 195.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. 124.

- ^ Yuanwu (2021).

- ^ Haskel (2022), p. 228, note 16.

- ^ Besserman & Steger 2011, p. 117.

- ^ Joshu (2001), p. 142.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. 3=.

- ^ a b Low 2006, p. 22.

- ^ a b Low 2006, p. 32-39.

- ^ Torei (2009), p. 172.

- ^ Hakuin 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Hakuin 2010, p. 125, 126.

- ^ Waddell 2002, p. 80.

- ^ a b Waddell 2009a, p. 83.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xxvii.

- ^ Hakuin 2009, p. 91, 93.

- ^ Waddell 2009a, p. 260-261 note 18.

- ^ Waddell 2010a, p. xxviii.

- ^ Hakuin 2009, p. 95.

- ^ a b Waddell 2009a, p. 84.

- ^ Hakuin 2009, p. 92.

- ^ Hakuin 2009, p. 93-94.

- ^ Hakuin 2009, p. 99-105.

- ^ a b Hakuin 2009, p. 105.

- ^ Hakuin 2009, p. 106-107.

- ^ Hakuin 2009, p. 106.

- ^ Hakuin 2009, p. 108-109.

- ^ Cleary (translator), Introduction to The Undying Lamp of Zen

- ^ Yampolski (1988), p. 156.

- ^ Ahn (2019).

- ^ a b Ahn (2019), p. 512.

- ^ a b Heine & Wright (2005), p. 151-152.

- ^ a b c d Ahn (2019), p. 513.

- ^ Griffith Foulk (1988), p. 165.

- ^ Mohr 2003, p. 312.

- ^ a b McDaniel 2013, p. 306.

- ^ Dumoulin 2005, p. 392.

- ^ Stevens 1999, p. 90.

- ^ Besserman & Steger 2011, p. 142.

- ^ Dumoulin 2005, p. 391.

- ^ Richard Bryan McDaniel (2013), Zen Masters of Japan. The Second Step East. Tuttle Publishing, p.306

- ^ Richard Bryan McDaniel (2013), Zen Masters of Japan. The Second Step East. Tuttle Publishing, p.310

- ^ a b Besserman & Steger 2011, p. 148.

- ^ Hori 2005b, p. 136.

- ^ Hori 2005b, p. 136-137.

- ^ Besserman & Steger 2011, p. 148-149.

- ^ Hori 2005b, p. 137.

- ^ Besserman & Steger 2011, p. 149.

- ^ Hori 2005b, p. 138.

- ^ a b Hori 2005b, p. 135.

- ^ Hori 2005b, p. 139.

- ^ Hori 2003, p. 23.

- ^ Hori 2003, p. 23-24.

- ^ Besserman & Steger 2011, p. 151.

- ^ Shore (1996).

- ^ The Hakuin Study Group has been researching the written works of Hakuin.

Sources

[edit]Printed sources

[edit]- Primary

- Bassui (2002), Mud and Water. The Collected Teachings of Zen Master Bassui, translated by Arthur Braverman, Wisdom Publications

- Cleary, Thomas (2002), Secrets of the Blue Cliff Record: Zen Comments by Hakuin and Tenkei, Shambhala

- Cleary, Thomas; Cleary, J.C. (2005), The Blue Cliff Record, Shambhala

- Hakuin, Ekaku (2006), Low, Albert (ed.), Hakuin on kensho, Shambhala

- Hakuin, Ekaku (2009), "Chapter 3: Idle Talk on a Night Boat", Hakuin's Precious Mirror Cave – Translator's Introduction, CounterPoint Press, ISBN 978-1-58243-475-9

- Hakuin, Ekaku (2010), Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, translated by Norman Waddell, Shambhala Publications, ISBN 9781570627705

- Hori, Victor Sogen (2003). Zen Sand: The Book of Capping Phrases for Kōan Practice (PDF). University of Hawaii Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2012-06-09.

- Low, Albert (2006), Hakuin on Kensho. The Four Ways of Knowing, Boston & London: Shambhala

- Reps, Paul; Senzaki, Nyogen (2008), Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: A Collection of Zen and Pre-Zen Writings, Tuttle, ISBN 978-0-8048-3186-4

- Sekida, Katsuki (1996), Two Zen Classics, Weatherhill

- Shore, Jeff (1996), Koan-Zen from the inside (PDF)

- Torei, Enji (2009), "The Chronological Biography of Zen Master Hakuin", in Waddell, Norman (ed.), Hakuin's Precious mirror Cave, Counterpoint

- Yuanwu (2021). The garden of flowers and weeds: a new translation and commentary on the Blue Cliff record. Matthew Juksan Sullivan. Rhinebeck, New York: Monkfish Book Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-948626-50-7. OCLC 1246676424.

- Secondary

- Ahn, Juhn Y. (2019), "Hakuin", in Kopf, G. (ed.), The Dao Companion to Japanese Buddhist Philosophy, Springer

- Besserman, Perle; Steger, Manfred (2011) [1991], Zen Radicals, Rebels, and Reformers, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 9780861716913

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005), Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 2: Japan, World Wisdom Books, ISBN 9780941532907

- Griffith Foulk, T. (1988), "The Zen Institution in Modern Japan", in Kraft, Kenneth (ed.), Grove Press

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Haskel, Peter (2022), Zen Master Tales, Shambhala

- Heine, Steven; Wright, Dale S. (2005). Zen Classics: Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517525-5. OCLC 191827544.

- Hori, Victor Sogen (2005b), The Steps of Koan Practice. In: John Daido Loori,Thomas Yuho Kirchner (eds), Sitting With Koans: Essential Writings on Zen Koan Introspection, Wisdom Publications

- Joshu (2001), The Recorded Sayings of Zen Master Joshu, translated by James Green, Shambhala

- Kimihiko, Naoki (1975), Hakuin zenji : KenkoÌ"hoÌ" to itsuwa (Japanese), Nippon Kyobunsha co., ltd., ISBN 978-4531060566

- Loori, John daido (2006), "Dogen and two Shobogenzo's", in Lori, John Daido (ed.), Sitting With Koans, Wisdom Publications

- McDaniel, Richard Bryan (2013), Zen Masters of Japan. The Second Step East, Tuttle Publishing

- Mohr, Michel. "Emerging from Non-duality: Kōan Practice in the Rinzai Tradition since Hakuin." In The Kōan: Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism, edited by S. Heine and D. S. Wright. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Mohr, Michel (2003), Hakuin. In: Buddhist Spirituality. Later China, Korea, Japan and the Modern World; edited by Takeuchi Yoshinori, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Stevens, John (1999), Zen Masters. A Maverick, a Master of Masters, and a Wandering Poet. Ikkyu, Hakuin, Ryokan, Kodansha International

- Tokiwa, Gishin (1991), "Hakuin Ekaku's Insight into 'the Deep Secret of Hen-Sho Reciprocity' and his Koan 'The Sound of a Single Hand'", Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies (Indogaku Bukkyogaku Kenkyu), 39 (2): 989–1883, doi:10.4259/ibk.39.989

- Trevor Leggett, The Tiger's Cave, ISBN 0-8048-2021-X, contains the story of Hakuin's illness.

- Waddell, Norman (2002). "Hakuin's Yasenkanna". The Eastern Buddhist. New Series. 34 (1): 79–119.

- Waddell, Norman (2009), "Translator's Introduction", Hakuin's Precious Mirror Cave, CounterPoint Press, ISBN 978-1-58243-475-9

- Waddell, Norman (2009a), "Chapter 3: Idle Talk on a Night Boat – Introduction", Hakuin's Precious Mirror Cave – Translator's Introduction, CounterPoint Press, ISBN 978-1-58243-475-9

- Waddell, Norman (2010a), "Foreword", Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, Shambhala Publications

- Waddell, Norman (2010b), "Translator's Introduction", The Essential teachings of Zen Master Hakuin, Shambhala Classics

- Yampolsky, Philip B. The Zen Master Hakuin: Selected Writings. Edited by W. T. de Bary. Vol. LXXXVI, Translations from the Oriental Classics, Records or Civilization: Sources and Studies. New York: Columbia University Press, 1971, ISBN 0-231-03463-6

- Yampolsky, Philip. "Hakuin Ekaku." The Encyclopedia of Religion. Ed. Mircea Eliade. Vol. 6. New York: MacMillan, 1987.

- Yampolski, P. (1988), "The Development of Japanese Zen", in Kraft, Kenneth (ed.), Grove Press

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Yoshizawa, Katsuhiro (1 May 2009), The Religious Art of Zen Master Hakuin, Catapult, ISBN 978-1-58243-986-0

Web-sources

[edit]- ^ a b Yoshizawa Katsuhiro, Views on Hakuin a Century after His Death (1868)

- ^ Shoinji Temple

- ^ Zen Buddhism: from perspective of Japanese Soto & Rinzai Zen Schools Archived 2012-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James Ford (2009), Teaching Credentials in Zen

- ^ Zen Master Hakuin's Letter in Answer to an Old Nun of the Hokke [Nichiren] Sect

- ^ Korinji – Lineage

- ^ Origins of the Ōtōkan Rinzai Lineage in Japan

- ^ Rinzai (Lin-chi) Lineage of Joshu Sasaki Roshi

Further reading

[edit]- Hakuin, Ekaku (2010), Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, translated by Norman Waddell, Shambhala Publications, ISBN 9781570627705

- Low, Albert (2006), Hakuin on Kensho. The Four Ways of Knowing, boston & london: Shambhala

- Yoshizawa, Katsuhiro (2010), The Religious Art of Zen Master Hakuin, Counterpoint Press

- Spence, Alan (2014), Night Boat: A Zen Novel, Canongate UK, ISBN 978-0857868541

External links

[edit]- Oxford Bibliographies – Hakuin

- Views on Hakuin a Century after His Death (1868)

- Barbara O'Brien, The Life, Teachings and Art of Zen Master Hakuin Archived 2012-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Terebess.hu, Hakuin Ekaku Selected Writings

- Ciolek, T. Matthew (1997–present), Hakuin School of Zen Buddhism (Hakuin's lineage)

- Don Webley, A Short Biography of Hakuin

- Ton Lathouwers, The Fundamental Koan and the First Vow of the Bodhisattva