Burrowing parrot

| Burrowing parrot | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Genus: | Cyanoliseus |

| Species: | C. patagonus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cyanoliseus patagonus (Vieillot, 1818)

| |

| |

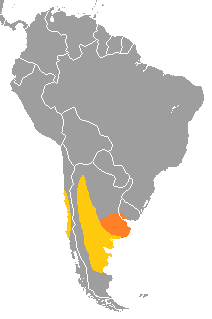

| yellow is nesting area, orange is area of seasonal food migrations | |

The burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus), also known as the burrowing parakeet or the Patagonian conure, is a species of parrot native to Argentina and Chile. It belongs to the monotypic genus Cyanoliseus, with four subspecies that are currently recognized.

The burrowing parrot is unmistakable with a distinctive white eye ring, white breast marking, olive green body colour, and brightly coloured underparts. Named for their nesting habits, burrowing parrots excavate elaborate burrows in cliff faces and ravines in order to rear their chicks. They inhabit dry, open country up to 2000 m in elevation.[2] Once abundant across Argentina and Chile, burrowing parrot populations have been in decline due to exploitation and persecution.[2]

Taxonomy, phylogeny and systematics

[edit]

The burrowing parrot was first described in 1818 by Louis Pierre Vieillot as Psittacus patagonus.[3] The genus was later renamed Cyanoliseus by Charles Lucien Bonaparte in 1854.[4]

The burrowing parrot is the only member of the genus Cyanoliseus, making it monotypic. Together with other genera of long-tailed New World parrots, Cyanoliseus is a part of the Tribe Arini, which in turn is a part of the subfamily Arinae, or Neotropical parrots, in the family of true parrots, Psittacidae. The closest relative of the burrowing parrot is thought to be the Nanday parakeet.[5][6]

There are four recognized subspecies, however the subspecies C. p. conlara is considered doubtfully distinct:[7]

- C. p. patagonus (Vieillot) is the nominate subspecies found in central to southeast Argentina, with some migrants reaching southern Uruguay[2]

- C. p. andinus (Dabbene and Lillo) is found in northwest Argentina, from Salta to San Juan.[2] Plumage is duller than the nominate C. p. patagonus, with much fainter markings.[8] This population is estimated to be approximately 2000 individuals.[9]

- C. p. conlara (Nores and Yzurieta) can be found in San Luis, between the ranges of C. p. patagonus and C. p. andinus, and is visually similar to C. p. patagonus except for a darker breast, suggesting that C. p. conlara may be a hybrid instead of a distinct subspecies[7][9]

- C. p. bloxami (Olson), formerly C. p. byroni, also known as the Greater Patagonian Conure,[10] is the Chilean sub-population. Formerly occurring from Atacama to Valdivia, this subspecies is now restricted to isolated populations in central Chile in the O'Higgins, Maule and Atacama regions.[2] Unlike the nominate subspecies, the white breast markings of this subspecies are prominent and extend across the whole breast, and the yellow underparts and red abdomen are much brighter.[8] It is larger in size than C. p. patagonus at 315-390g.[10] Populations are currently estimated at 5000-6000 individuals.[9]

Another subspecies, C. p. whitleyi (Kinnear), was described but has since been determined to be an aviary hybrid between a burrowing parrot and a species from the genus Aratinga or possibly Primolius.[2][8]

A study on mitochondrial DNA in burrowing parrots suggests that the species originated in Chile, the Argentinian populations arising during the Late Pleistocene from "a single migration event across the Andes, which gave rise to all extant Argentinean mitochondrial lineages".[9] The Andes represent a strong geographical barrier, thus isolating the Chilean population, which were found to be genetically and phenotypically distinct from the Argentinian populations.[9] This study found no support for C. p. conlara as a subspecies, and instead suggests a hybrid zone between the C. p. patagonus and C. p. andinus ranges where C. p. conlara represents the hybrid phenotype.

Description

[edit]Adults measure 39–52 cm in length, with a wingspan of 23–25 cm and a long, graduated tail that can range from 21 to 26 cm. Burrowing parrots are slightly sexually dimorphic, with males being slightly larger and weighing approximately 253-340 g, while females weigh 227-304 g,[2][8] making it the largest member of the group of New World parakeet species commonly known as conures.[11]

The burrowing parrot is a distinctive parrot; it has a bare, white eye ring and post-ocular patch, its head and upper back are olive-brown, and its throat and breast are grey-brown with a whitish pectoral marking, which is variable and rarely extends across the whole breast.[2][8] The lower thighs and the center of the abdomen are orange-red, and it is thought that the extent and hue of the red plumage indicates the quality of the individual as a breeding partner and parent.[12] The lower back, upper thighs, rump, vent and flanks are yellow, and the wing coverts olive green.[2] The tail is olive green with a blue caste when viewed from above and brown from below.[8] The burrowing parrot has a grey bill and yellow-white iris with pink legs.[8] Immature birds look like adults but with a horn coloured upper mandible patch and a pale grey iris.[2][8]

While both sexes look visually similar to the human eye, the burrowing parrot is sexually dichromatic. Males tend to have significantly redder and larger abdominal red patches,[12] and both sexes look different under UV light, with males have brighter green feathers and females having brighter blue feathers.[13]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The burrowing parrot can be found in much of Argentina, and there are isolated populations in central Chile.[2] In the winter, birds in central and southern Argentina may migrate north as far as southern Uruguay, making them austral migrants, while Chilean birds migrate vertically down slope to avoid colder altitudes.[8] Movements in the populations of northwestern Argentina are also known to occur according to food availability.[8]

The burrowing parrot prefers dry, open country, particularly in the vicinity of water courses, up to 2000 m in elevation.[2] Habitats include montane grassy shrubland, Patagonian steppes, arid lowland, woodland savanna, and the plains of the Gran Chaco.[2][8] They may also inhabit farmland and the edges of urban areas.[2]

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]Diet

[edit]The diet of the burrowing parrot comprises seeds, berries, fruits, and possibly vegetable matter,[8] and they can be seen feeding on the ground or in trees and shrubs.[2] Their diet varies seasonally, with fruit consumption peaking during Argentina's summer (December–February), where one study found that fruit makes up 2% of their crop contents in November–December, 74% in January, 25% in February, 35%,in March and 8% in April.[8] Specifically, burrowing parrots have been observed feeding on the fruit from various species such as the red crowberry (Empetrum rubrum), Chilean palo verde (Geoffroea decorticans), Lycium salsum, pepper trees (Schinus sp.), Prosopis sp., Discaria sp., as well as cacti.[2] In the winter, the burrowing parrot feeds predominantly on seeds from cultivated crops and wild plants such as thistles, as well as the Patagonian oak (Nothofagus obliqua) and the Carboncillo (Cordia decandra) in the Chilean foothills.[2]

Reproduction

[edit]Best known for its nesting habits, the burrowing parrot excavates industrious burrows in limestone or sandstone cliff faces, often in ravines. These burrows can be as much as 3 m deep into a cliff-face, connecting with other tunnels to create a labyrinth, ending in a nesting chamber.[8] Breeding pairs will reuse burrows from previous years but may enlarge them.[14] They nest in large colonies, some of the largest ever recorded for parrots, which is thought to reduce predation.[14] The parrots tend to select larger, taller ravines, allowing for larger colonies and higher burrows and resulting in higher breeding success.[14]

In the absence of acceptable ravines or cliffs to use as nesting sites, burrowing parrots will use anthropogenic substrates such as quarries, wells and pits.[15] Rarely, they have been known to nest in tree cavities.[16]

Studies have shown that burrowing parrots are both socially and genetically monogamous.[17] The breeding season begins in September, and eggs are laid up to December, with two up to five eggs laid per clutch.[2] The incubation period is 24–25 days, where the female is the sole incubator while the male provides for her.[18] Eggs hatch asynchronously, and mortality is higher for fourth and fifth chicks in a clutch.[18] Both parents care for the chicks. Chicks begin to fledge in late December until February, approximately eight weeks after hatching,[8] and the fledglings depend on their parents for up to four months.[18]

Thermoregulation

[edit]In order to cope with an unpredictable climate, burrowing parrots increase their body mass and decrease their basal metabolic rate (BMR) in the winter in order to conserve energy, insulate against cold ambient temperatures and to survive reductions in food availability, in concurrence with other birds found in the southern hemisphere.[19]

Status and relationship to humans

[edit]

The burrowing parrot currently has an overall conservation status of least concern according to the IUCN Red List, but populations are currently declining, due to exploitation for the wildlife trade and persecution as a crop pest.[20] Their nesting habits make them particularly vulnerable to human disturbances and habitat degradation.[2] It is nonetheless currently listed under Appendix II of CITES, allowing for international trade,[2] but the endangered C. p. bloxami Chilean subspecies is on the Chilean national vertebrate red list.[9]

The burrowing parrot was officially named as a crop pest in Argentina in 1984, leading to increased persecution.[2] Their status as a crop pest has excluded them protection under Argentina's ban on wildlife trade,[2] however the province of Río Negro has deemed population reductions sufficient and banned hunting and trade of the burrowing parrot as of 2004.[9] Studies have shown that the effects of crop predation by burrowing parrots is economically insignificant.[21] Additionally, birds of the Chilean subspecies (C. p. bloxami) have been hunted for feast-day in Chile.[2]

The Mapuche people of the province of Neuquén in the Patagonian Andes celebrate the annual fledging of burrowing parrots with a festival.[22]

Aviculture

[edit]The burrowing parrot, commonly called the Patagonian conure in aviculture, is a popular companion parrot. It is known for being playful, gentle and affectionate with humans, even cuddly when tame - it can also learn to talk and mimic sounds from its environment. As a large parakeet, it requires plenty of living space and the opportunity to fly on a regular basis in order to thrive.[23] The maximum verified lifespan for this species in captivity is 19.5 years, however plausible claims of burrowing parrots living up to 34.1 years have also been reported.[24]

The subspecies typically found in aviculture is the nominate ssp., Cyanoliseus patagonus patagonus - also known as the lesser Patagonian conure. Tens of thousands of burrowing parakeets were previously removed from the wild and exported for the pet trade, but most birds available for purchase as pets are nowadays captive-bred.[25]

References

[edit]![]() Media related to Cyanoliseus patagonus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cyanoliseus patagonus at Wikimedia Commons

- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Cyanoliseus patagonus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22685779A132255876. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22685779A132255876.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Collar, Nigel; Boesman, Peter F. D. (2020-03-04), Billerman, Shawn M.; Keeney, Brooke K.; Rodewald, Paul G.; Schulenberg, Thomas S. (eds.), "Burrowing Parakeet (Cyanoliseus patagonus)", Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, doi:10.2173/bow.burpar.01, S2CID 241425121, retrieved 2020-10-15

- ^ Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l'agriculture, à l'économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine, etc. Vol. t.25 (1817) (Nouv. éd. presqu' entièrement refondue et considérablement angmentée. ed.). Paris: Chez Deterville. 1817. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.20211.

- ^ Bonaparte, Charles Lucien (1857). Opera ornithologica. Vol. 2. Paris?.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Tavares, Erika Sendra; Baker, Allan J.; Pereira, Sérgio Luiz; Miyaki, Cristina Yumi (2006-06-01). "Phylogenetic Relationships and Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Parrots (Psittaciformes: Psittacidae: Arini) Inferred from Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Sequences". Systematic Biology. 55 (3): 454–470. doi:10.1080/10635150600697390. ISSN 1076-836X. PMID 16861209.

- ^ Wright, Timothy F.; Schirtzinger, Erin E.; Matsumoto, Tania; Eberhard, Jessica R.; Graves, Gary R.; Sanchez, Juan J.; Capelli, Sara; Müller, Heinrich; Scharpegge, Julia; Chambers, Geoffrey K.; Fleischer, Robert C. (2008-07-24). "A Multilocus Molecular Phylogeny of the Parrots (Psittaciformes): Support for a Gondwanan Origin during the Cretaceous". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 25 (10): 2141–2156. doi:10.1093/molbev/msn160. ISSN 1537-1719. PMC 2727385. PMID 18653733.

- ^ a b Forshaw, Joseph Michael (2010). Parrots of the world. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3620-8. OCLC 705945316.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Forshaw, Joseph M. (1989). Parrots of the World (3rd ed.). Willoughby, NSW, Australia: Lansdowne Editions. pp. 470–472. ISBN 0-7018-2800-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Masello, Juan F.; Quillfeldt, Petra; Munimanda, Gopi K.; Klauke, Nadine; Segelbacher, Gernot; Schaefer, H. Martin; Failla, Mauricio; Cortes, Maritza; Moodely, Yoshan (15 June 2011). "The high Andes, gene flow and a stable hybrid zone shape the genetic structure of a wide-ranging South American parrot". Frontiers in Zoology. 8: 16. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-8-16. PMC 3142489. PMID 21672266.

- ^ a b "Patagonian Conure". World Parrot Trust. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "Types of conures | with pictures! - Psittacology". Psittacology. 13 April 2020.

- ^ a b MASELLO, Juan F.; PAGNOSSIN, María Luján; LUBJUHN, Thomas; QUILLFELDT, Petra (2004-06-18). "Ornamental non-carotenoid red feathers of wild burrowing parrots". Ecological Research. 19 (4): 421–432. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1703.2004.00653.x. ISSN 0912-3814. S2CID 6123165.

- ^ Masello, Juan F.; Lubjuhn, T.; Quillfeldt, Petra (August 2009). "Hidden dichromatism in Burrowing Parrots Cyanoliseus patagonus as revealed by spectrometric colour analysis". Hornero. 24: 47. doi:10.56178/eh.v24i1.729. hdl:20.500.12110/hornero_v024_n01_p047. S2CID 55392503 – via Research Gate.

- ^ a b c Ramirez-Herranz, Myriam; Rios, Rodrigo S.; Vargas-Rodriguez, Renzo; Novoa-Jerez, Jose-Enrique; Squeo, Francisco A. (2017-04-26). "The importance of scale-dependent ravine characteristics on breeding-site selection by the Burrowing Parrot, Cyanoliseus patagonus". PeerJ. 5: e3182. doi:10.7717/peerj.3182. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5408729. PMID 28462019.

- ^ Tella, José L.; Canale, Antonela; Carrete, Martina; Petracci, Pablo; Zalba, Sergio M. (2014). "Anthropogenic Nesting Sites Allow Urban Breeding in Burrowing ParrotsCyanoliseus patagonus". Ardeola. 61 (2): 311–321. doi:10.13157/arla.61.2.2014.311. hdl:11336/21787. ISSN 0570-7358. S2CID 84131010.

- ^ Zungu, Manqoba M.; Brown, Mark; Downs, Colleen T. (2018). "Seasonal thermoregulation in the burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus)". Journal of Thermal Biology. 38 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2012.10.001. ISSN 0306-4565. PMID 24229804.

- ^ Masello, Juan F.; Sramkova, Anna; Quillfeldt, Petra; Epplen, Jörg Thomas; Lubjuhn, Thomas (24 July 2002). "Genetic monogamy in burrowing parrots Cyanoliseus patagonus?". Journal of Avian Biology. 33 (1): 99–103. doi:10.1034/j.1600-048x.2002.330116.x. ISSN 0908-8857.

- ^ a b c Masello, Juan F.; Quillfeldt, Petra (2002). "Chick Growth and Breeding Success of the Burrowing Parrot". The Condor. 104 (3): 574. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2002)104[0574:cgabso]2.0.co;2. ISSN 0010-5422.

- ^ Zungu, Manqoba M.; Brown, Mark; Downs, Colleen T. (January 2013). "Seasonal thermoregulation in the burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus)". Journal of Thermal Biology. 38 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2012.10.001. ISSN 0306-4565. PMID 24229804.

- ^ International), BirdLife International (BirdLife (2018-08-07). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Cyanoliseus patagonus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- ^ Sánchez, Rocío; Ballari, Sebastián A.; Bucher, Enrique H.; Masello, Juan F. (2016-06-27). "Foraging by burrowing parrots has little impact on agricultural crops in northeastern Patagonia, Argentina". International Journal of Pest Management. 62 (4): 326–335. doi:10.1080/09670874.2016.1198061. hdl:11336/129774. ISSN 0967-0874. S2CID 89257448.

- ^ Masello, Juan F.; Quillfeldt, Petra (2004). "News from El Cóndor, Patagonia,Argentina". PsittaScene.

- ^ "Patagonian Conure Health, Personality, Colors and Sounds". 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Patagonian conure (Cyanoliseus patagonus) longevity, ageing, and life history". The Animal Ageing and Longevity Database. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "Patagonian Conure Fact Sheet". 2 January 2013.